Lastingham

Lastingham is a village and civil parish which lies in the Ryedale district of North Yorkshire, England. It is on the southern fringe of the North York Moors, 5 miles (8 km) north-east of Kirkbymoorside, and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to the east of Hutton-le-Hole. It was home to the early missionaries to the Angles, St. Cedd and his brother, St. Chad. At the 2001 census, the parish had a population of 96,[2] increasing to 233 (including Spaunton) at the 2011 Census.[1] It is in the historic North Riding of Yorkshire.

| Lastingham | |

|---|---|

Lastingham village | |

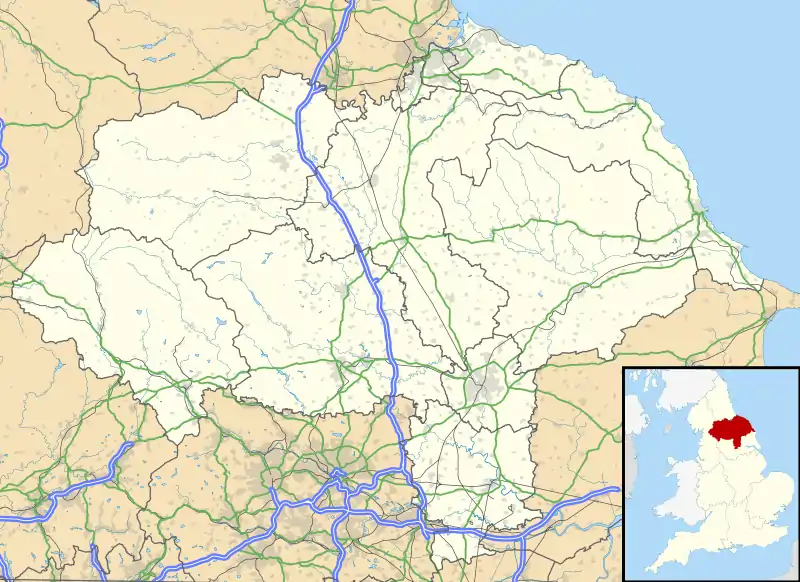

Lastingham Location within North Yorkshire | |

| Population | 233 (2011 census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SE7290 |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | YORK |

| Postcode district | YO62 |

| Dialling code | 01751 |

| Police | North Yorkshire |

| Fire | North Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| UK Parliament | |

History

There is reason to believe that the original name for Lastingham was Læstingau.[3] Læstingau first appears in history when King Ethelwald of Deira (651-c.655) founded a monastery for his own burial. Bede attributes the initiative to Ethelwald's chaplain Caelin, brother of Cedd, Chad and Cynibil. Bede records that Cedd and Cynibil consecrated the site, and that Cynibil built it of wood. Cedd ruled the monastery as the first abbot until his death, combining this position with that of missionary bishop to the East Saxons. In 664, shortly after the Synod of Whitby, in which he was a key participant, St. Cedd died of the plague at Læstingau. Bede records that a party of monks from Essex came to mourn him and all but one were all wiped out by the plague. Cedd was first buried outside the wooden monastery but, at some time between 664 and 732, a stone church was erected, and his body was translated to the right side of the altar. The crypt of the present parish church remains a focus for veneration of Cedd.[4] His brother St. Chad took his place as abbot.[5]

Not much is known of this house, though all who spoke of it spoke well. Perhaps the best indication of its standards is that, in 687, one of its graduates, Trumbert, transferred to Wearmouth-Jarrow and became scriptural tutor to a youthful Bede.[6]

It is not known what became of the original Anglo-Saxon structure. Destruction by the Danes is nowhere attested, and seems to be entirely the product of modern conjecture. An attempt was made to rebuild the monastery in 1078, when St. Stephen, prior of Whitby, and a band of monks moved from Whitby due to a disagreement with William de Percy, who was abbot of Whitby at the time.[7] They received support from King William I and Berenger de Todeni in the form of one carucate of land in Lastingham, six carucates at Spaunton, and other lands in Kirkby. They remained on the site only eight years due to persistent harassment by bandits. In 1086 they moved to York, and founded St Mary's Abbey there, to which they annexed the lands of the monastery at Lastingham.[8]

The place where the monastery was located is now the Church of St Mary, which attracts many visitors due to its rare Norman architecture and crypt with an apsidal chancel.[9]

There is also a War Memorial commemorating soldiers from Lastingham and Spaunton who served in the First World War.[10]

- Church of Saint Mary

from the south

from the south nave

nave font

font crypt

crypt capitals in the crypt

capitals in the crypt

Notable people

- Saint Cedd (620–664), saint[11]

- Saint Chad (634–672), saint[12]

- Trumbert, scriptural tutor[13]

- John Edward Hine, bishop[14]

- John Jackson (1778–1831), painter[15]

- Sydney Ringer, physician and originator of Ringer's Solution[16]

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Lastingham Parish (1170217262)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "Census 2001: Parish Headcounts: Ryedale". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Ekwall, Eilert (1960). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names (4th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 289. ISBN 0-19-869103-3.

- This crypt is generally held to be the only complete crypt in the U.K., containing a central aisle, two side aisles, and an apse.

- Bede: Historia Ecclesiastica, iii, 25.

- Bede: Historia Ecclesiastica, iv, 3.

- Simeon of Durham: Historia Regum Angliae (part two) @ 1074

- GENUKI "Lastingham Parish information from Bulmers' 1890": http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/NRY/Lastingham/Lastingham90.html

- Jenkins, Simon (2000). England's thousand best churches. London: Penguin Books. p. 778. ISBN 0-14-029795-2.

- http://www.ww1-yorkshires.org.uk/html-files/lastingham.htm

- Farmer, D H (23 September 2004). "Cedd [St Cedd]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4985. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Farmer, D H (23 September 2004). "Ceadda [St Ceadda, Chad]". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4970. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Warner, Richard Hyett (1871). Life and legends of Saint Chad, bishop of Lichfield, (669-672). Wisbech: Leach. pp. 25–26. OCLC 319901071.

- "Hine, John Edward". Who's Who. ukwhoswho.com (June 2020 online ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. Retrieved 11 June 2020. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Owen, Felicity (23 September 2004). "Jackson, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14532. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Orchard, C H (23 September 2004). "Ringer, Sydney". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35759. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lastingham. |