Las Vegas in the 1940s

Las Vegas in the 1940s was notable for the establishment of The Strip in a town which "combined Wild West frontier friendliness with glamor and excitement".[1] In 1940, the population was 8,400 but within five years, it more than doubled its size.[2] The Las Vegas Valley had a population of 13,937 in 1940, increasing to 35,000 in just two years.[3]

1940–44

In the early 1940s, the town experienced political problems resulting in two city governments, each claiming to have the right to rule. The militarization of Las Vegas began when the Army Gunnery School (now Nellis Air Force Base) was established in 1941; between 1941–45, 55,000 students attended classes here. The city of Henderson was established in 1941.[4]

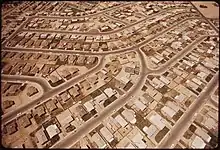

During the World War II period, when defense spending was high, tourist traffic to Las Vegas necessitated raising of many new buildings on the Fifth street, Fremont Street and many other prime roads leading to the casinos. During the 40s and also in the 50s the resort sector also developed in a big way to the detriment of the residential houses in many of the residential streets.[5] Suburbs with single family housing complexes and apartment blocks sprung up behind El Rancho and other hotels on The Strip. The city also modified its grid pattern layout, as the city extended southwards and realigned in north-south direction. As the casinos came into existence on the Strip along the Fremont street, the commercial establishments were moved to the Main Street and Commerce Street.[6]

In 1940, the Clark Inn Motel was built as a Regency modern type hotel. In the same year, the Chief Hotel came into existence as a remodeled version of the mission hotel. Both these were built on the Charleston Boulevard in the 1200 block. During the second World War period, the Las Vegas Boulevard witnessed proliferation of wedding chapels, auto courts and motels.[5] In 1940, the hotel magnate of California, Hull was invited by James Cashman of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce to build one of his El Rancho Hotels with casino, which would be profitable. Cashman and his associates showed him a number of sites. But Hull had his own preference and built the El Rancho Las Vegas hotel at a large site of his choice. He built the hotel with a sprawling casino, coffee shops upscale restaurants, well-turned gardens and parks, swimming pool and a large parking lot which could accommodate 500 cars.[7] Following this hotel, the next seven years witnessed the emergence of Last Frontier, Flamingo and Thunderbird hotels. It was built in the low rise western architectural style at the early developmental stage of The Strip. The El Rancho Vegas opened in 1941 on what became the Las Vegas Strip, serving as the model for future casinos.[8] In 1942, Clark Gable was staying at the El Rancho when he learned that his wife Carole Lombard was in a commercial airplane crash near Las Vegas at Goodsprings, Nevada, in which there were no survivors.

In 1941, John Grayson established the El Cortez Hotel and Casino. The Arizona Club, also known as the "Queen of Block 16", was the first Las Vegas saloon to have second story constructed for prostitution and was unchallenged until 1941. In 1942, Las Vegas closed its prostitution district, accommodating a request from the military, and by December 1942, bars and casinos were closed for an eight-hour period, starting at 2:00 AM.[9] The West Side Club opened for African American customers in the early 1940s as, in 1942, Las Vegas city commissioners denied a permit for an interracial hotel-casino in the Downtown area. The Hotel Last Frontier was established in 1942. Its Western Frontier Village contained The Little Church of the West where Betty Grable and Harry James married in 1943. By 1944, the Army base's training range had been enlarged to 3.3 million acres. A riot in that year, resulting from an altercation between the police and black GIs who wanted to enter downtown bars and casino.[10] The Huntridge Theater was built in 1944.[11]

At 16.5 percent of the labor pool, women made up a small minority of workers in 1940, numbering slightly more than 1,000. About half were in service, sales, or clerical work with thirteen percent in professional jobs, 10 percent working as proprietors or managers, another 10 percent engaged in domestic service, and the balance working in some operative business. In the decade of the 1940s, though the number of women of working age women increased 196 percent, their participation in the workfoce increased 413 percent.[12]

1945–49

The post-war era was one of celebration for Las Vegas's tourism industry as all war period restrictions were lifted and tourist traffic boomed.[13] A colorful feature of entertainment in the Last frontier in 1945 was the dancing shows of chorus girls. One of the chorus leading girl became the entertainment director of El Rancho Vegas.[14] In 1945, Nevada Power Company noted that 77 million kilowatt-hours of electricity were being used by its customers. This more than doubled in two years, reaching almost 160 million kilowatt-hours.[15] In December 1946, the Flamingo Hotel was opened by Bugsy Siegel and in the following year, the "Howdy, Pardner" city symbol (nicknamed Vegas Vic) was erected. Rededicated by an act of Congress in 1947, the Boulder Dam was renamed the Hoover Dam. By 1948, the Strip contained several casinos, including the El Rancho, Last Frontier, Fabulous Flamingo, and Thunderbird (later renamed Silverbird). Las Vegas' expansion beset the town with water shortages such that faucets ran dry at the Las Vegas Hospital in 1949.[11] In the same year, the Nevada Natural Gas Company began coordination of a 144 miles (232 km) natural gas pipeline between the city and Topock, Arizona.[16] With the dramatic growth of Las Vegas, the increasing water supply needs of the city and the county was brought to focus in 1946, in view of the county's inadequate ground water potential to meet the demand. Lake Mead was identified as a potential solution to the problem. The dismal sanitary conditions of the city was also discussed and sought to be resolved. In January 1946, efforts made by some lobbies to lift the ban on prostitution were turned down on health grounds.[17]

H.K. Rothman, p. 103, 310

During World War II, the Rockwell Field which was a civilian airport of Las Vegas and Clark County since 1926 was closed and the new airport became a military base of the U.S. Army Air Corps from 1941 and functioned as "flexible gunnery training school". This airport was named as McCarran Airport, in honour of Patrick McCarran, the then U.S. senator of Nevada. After the war, the gunnery school was closed but the air force, in 1947, wanted to continue operating the airport for military purposes only. As a result, a new civilian airport location had to be chosen. This was selected at the Alamo Field. Clark County bought this land from its owner George Crockett but permitting him to retain his business in the airport.[18] After the war ended, as part of tourism promotion, a new county airport was built starting with a referendum in May 1947 and commissioned on 19 December 1948. It served for 15 years till the jet planes made the airport ineffective.[19] The stone pillars which marked the entrance to the old McCarran Airport were shifted to the new airport and rededicated to McCarran.[18]

Railroad underpasses were also planned and built by the Municipal authorities, and one such underpass which was built in 1949 on the Las Vegas western lands at West Charleston which was aimed to achieve the goal of extending the city westwards.[5]

See also

References

- Garman, Rick (12 September 2012). Frommer's Las Vegas 2013. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-1-118-33380-8.

- "Federal Projects and Las Vegas". PBS. 11 July 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- Ainlay, Thomas Taj; Gabaldon, Judy Dixon (2003). Las Vegas: The Fabulous First Century. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 30, 43, 60, 62, 55, 63, 64, 102–. ISBN 978-0-7385-2416-0.

- Rothman, p. 77

- MoehringGreen 2005, p. 108.

- MoehringGreen 2005, p. 109.

- MoehringGreen 2005, pp. 109–10.

- Koch, Ed; Manning, Mary; Toplikar, Dave (15 May 2008). "Showtime: How Sin City evolved into 'The Entertainment Capital of the World'". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Rothman, p. 313

- Rothman, p. 264

- Simich, Jerry L.; Wright, Thomas C. (2005). The Peoples of Las Vegas: One City, Many Faces. University of Nevada Press. pp. 5, 6, 64, 82, 105, 128, 165–. ISBN 978-0-87417-616-2.

- Rothman, Hal K.; Davis, Mike (2002). The Grit Beneath the Glitter: Tales from the Real Las Vegas. University of California Press. pp. 247, 248, 253. ISBN 978-0-520-22538-1.

- MoehringGreen 2005, p. 111.

- MoehringGreen 2005, p. 112.

- Rothman, p. 103

- Rothman, p. 104

- MoehringGreen 2005, pp. 117–118.

- "McCarran International Airport". Online Nevada organization. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- MoehringGreen 2005, pp. 114–15.

Bibliography

- Eugene P. Moehring; Michael S. Green (2005). Las Vegas: A Centennial History. University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-615-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg.webp)