Léon Davent

Léon Davent was a French printmaker in the mid 16th century, closely associated with the First School of Fontainebleau. He worked in both engraving and etching and many of his works are based on designs by Francesco Primaticcio, "rendered boldly and freely".[1] Others use designs by Luca Penni and other artists. It is thought that there was a workshop at the Palace of Fontainebleau itself in the 1540s, where he was one of the leading printmakers. Their main purpose seems to have been to record the new style being forged at Fontainebleau, copying both the main subject paintings and the elaborate ornamental stuccos and other decorations.

With a couple of exceptions his prints are signed only with "L.D.", and his identity was long uncertain; he is known as the Master L.D. in older literature. Lists of his works have attributed between 98 (Henri Zerner) and 226 (F. Herbet) prints to him.[2]

Life

Very little is known about his life; his dated prints run between 1540 and 1556,[3] when he left a series incomplete, which may indicate his death.[4] There is no evidence that he trained as a painter, and like many early engravers he may have been trained as a goldsmith, a trade where engraving was still important. His engravings, which are presumed to be his earliest works, show a considerable fluency in this difficult technique.[5] According to Henri Zerner, he may have produced about 9 early prints before moving to Fontainebleau, and he may only have started etching, rather than engraving, in about 1540.[6] Others see him as only beginning to make engravings in 1540, when his first dated print appears, and etchings from about 1543–1544.[7] Once the switch had been made, he only made etchings.[8] He was perhaps taught etching by Antonio Fantuzzi, one of the Italians at Fontainebleau, and in turn seems to have passed some of his experience of techniques in engraving on to him.[9]

Apart from Penni and Primaticcio, who he knew, he made prints after drawings brought from Italy, presumably by Primaticcio, by Giulio Romano and Parmigianino, but not Rosso Fiorentino, unlike Fantuzzi and "Master I♀V".[10]

In about 1546 he seems to have left France, perhaps in the company of Luca Penni, as a number of prints dated 1546 or 1547 are based on designs by Penni, and printed on paper from Germany (as it then was). These also use black ink and "the printing has a hard, professional look".[11] He produced some of the illustrations for Les Quatre Premiers Livres des navigations et pérégrinations orientales by the geographer and valet de chambre Nicolas de Nicolay, published in Lyon in 1548. Henri Zerner only attributed 3 of the illustrations to him, while Herbet gives him 61.[12]

In the 1550s Davent was in Paris, again using Penni's designs. As "Lion Davant" he signed a contract in 1555 to produce illustrations for a book called Livre de la diversitée des habits du Levant ("Book of the different costumes of the Levant"), again by de Nicolay. Davent's latest print for the book is dated 1556, but the published book only contains 61 plates, rather than the 80 in the contract.[13] The publication of this contract by Catherine Grodecki in 1974 ended the discussion over the identity of "Master L.D."; there had been a number of other suggestions, in particular Léonard Thiry. He also worked closely with Antonio Fantuzzi,[14] and did etch a number of designs by Thirly.[15] In the contract of November 1555 he was recorded as living on the Rue Saint-Jacques.[16]

The Fontainebleau workshop

Although there is no certain proof, most scholars have agreed that there was a printmaking workshop at the Palace of Fontainebleau itself, reproducing the designs of the artists for their works in the palace, as well as other compositions they produced. The most productive printmakers were Davent, Fantuzzi, and Jean Mignon, followed by the "mysterious" artist known from his monogram as "Master I♀V" (♀ being the alchemical symbol for copper, from which the printing plates were made),[17] and the workshop seems to have been active between about 1542 and 1548 at the latest; François I of France died in March 1547, after which funding for the palace ended, and the school dispersed. These were the first etchings made in France, and not far behind the first Italian uses of the technique, which originated in Germany.[18] The earliest impressions of all the Fontainebleau prints are in brown ink, and their intention seems to have been essentially reproductive.[19]

The intention of the workshop was to disseminate the new style developing at the palace more widely, both to France and to the Italians' peers back in Italy. Whether the initiative to do this came from the king or another patron, or from the artists alone, is unclear. David Landau believes that Primaticcio was the driving force;[20] he had stepped up to become the director of the work at Fontainebleau after the suicide of Rosso Fiorentino in 1540.[21]

The enterprise seems to have been "just slightly premature" in terms of catching a market. The etched prints were often marked by signs of the workshop's inexperience and sometimes incompetence with the technique of etching, and according to Sue Welsh Reed: "Few impressions survive from these plates, and it is questionable whether many were pulled. The plates were often poorly executed and not well printed; they were often scratched or not well polished and did not wipe clean. Some may have been made of metals soft as copper, such as pewter."[22] A broadening market for prints preferred the "highly finished textures" of Nicolas Beatrizet, and later "proficient but ultimately uninspired" engravers such as René Boyvin and Pierre Milan.[23]

Works, style and technique

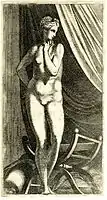

David Landau describes one of his etchings (Female Nude Standing, see gallery) as representing "the imaginative recording of new artistic expression" in an "experimental etching ... full of adventurous lighting devices and daring chiaroscuro, but also defaced by the spots of foul biting and incompetent printing".[24]

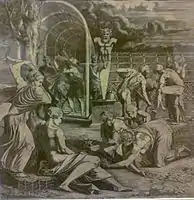

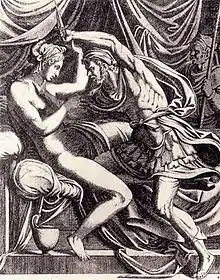

Cadmus fighting the Dragon is a large (9 13/16 in. × 12 in. (25 × 30.5 cm) with small margins) and highly finished etching, to a design by Primaticcio, that is one of his most highly regarded prints. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it "provides an excellent example of Davent's preference for an all-over gray tone, from which a few lighter areas stand out, giving subtle relief to the forms. This is achieved firstly by covering almost the entire surface of the plate, including the sky, with a close-knit web of lines. Davent also left most of the plate rough—or even, in the case of this print, deliberately roughened it—so that it would hold a film of ink. Only a few areas are polished smooth, hold little ink, and read as highlights".[25]

The obscurity of the subject is very typical of the School of Fontainebleau, and at times Jason, Theseus and Hercules have all been proposed as the hero, but it fits much better with the story of Cadmus, the legendary founder of Thebes, as told by Ovid. It seems to form part of a cycle of five prints on the story of Cadmus, the others by Fantuzzi, Master I♀V, and two unidentified hands.[26]

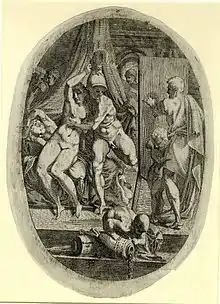

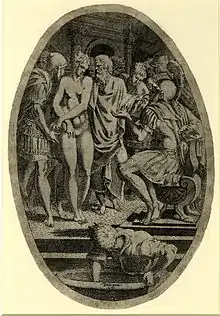

Davent did three etchings in vertical oval format after the cycle of frescos in the bedroom of Francois I's mistress, the Duchess of Étampes (1508–1580), from which a total of eleven compositions surviving today are known. The cycle showed the life of Alexander the Great, but with little emphasis on his military career. Some survive in situ, though heavily repainted and perhaps moved within the room, which was remodelled more than once, and is now part of the "King's Staircase". Others survive in prints and drawings; the subject with the story of Alexander, Apelles and Campaspe was also etched by Master I♀V, and is recorded in a preparatory drawing at Chatsworth House. The oval paintings were set in much larger stucco frames, with a standing female nude to either side and much else besides; several of these survive.[27]

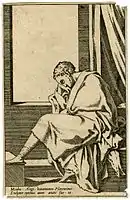

An etching of Michelangelo at the Age of Twenty-Three (see gallery) is "somewhat, but not altogether, surprising" as a subject in France some forty years after 1498, when Michelangelo was that age. It is identified by the inscription beneath, but is not signed by "L.D.", unlike most of Davent's prints. It is certainly not "an actual likeness, since the figure is not in the least individualized". Henri Zerner suggests "most tentatively" that 1498 was the date the sculptor signed the contract for his Pietà, now in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican City with the French ambassador in Rome, Cardinal Jean de Bilhères, who commissioned the work. A French audience might therefore regard this point in his life as especially significant.[28]

Female Nude Standing, perhaps Venus. After Primaticcio, height 280 millimetres (trimmed)

Female Nude Standing, perhaps Venus. After Primaticcio, height 280 millimetres (trimmed) Soldiers bringing Timoclea, naked, before Alexander the Great, enthroned in the foreground; c.1541/45. After Primaticcio, height 341 mm (trimmed), width: 231 mm. Signed "Bologna L.D."

Soldiers bringing Timoclea, naked, before Alexander the Great, enthroned in the foreground; c.1541/45. After Primaticcio, height 341 mm (trimmed), width: 231 mm. Signed "Bologna L.D." Michelangelo at the Age of Twenty-Three, inscribed "Micha . Ange . bonarotanus . Florentinus . Sculptor optimus anno aetatis sue . 23"

Michelangelo at the Age of Twenty-Three, inscribed "Micha . Ange . bonarotanus . Florentinus . Sculptor optimus anno aetatis sue . 23"

The Garden of Pomona, after Primaticcio

The Garden of Pomona, after Primaticcio

Scene of Fishing

Scene of Fishing

Notes

- Grivel

- Grivel; Boorsch, 469. These say Herbet's list included 221 and 226 prints respectively.

- Boorsch, 469

- Grivel

- Boorsch, 249; Reed, 31

- Boorsch, 469

- Grivel; Boorsch, 83; Reed, 29

- Boorsch, 249

- Reed, 29–31

- Boorsch, 81–82 (see Table 1), 86

- Boorsch, 88, 469

- Grivel; Boorsch, 89

- Grivel

- Benezit

- Boorsch, 265

- Boorsch, 89; Reed, 29

- Boorsch, 80–83

- Boorsch, 80–81; Landau, 308–309

- Boorsch, 80–81

- Boorsch, 95; Landau, 309

- Boorsch, 79

- Reed, 27

- Landau, 309

- Landau, 309

- "Cadmus fighting the Dragon", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Boorsch, 250–251; Reed, 31

- Boorsch, 256–257, 268–269; version by Master I♀V, at the British Museum; Photo of one of the frames

- Boorsch, 264–265 – this catalogue entry is by Henri Zerner

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Léon Davent. |

- Benezit: "DAVENT, Léon." Benezit Dictionary of Artists, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed January 6, 2017, subscription required

- Boorsch, Suzanne, in: Jacobson, Karen (ed), (often wrongly cat. as George Baselitz), The French Renaissance in Prints (most relevant text by Suzanne Boorsch or Henri Zerner), 1994, Grunwald Center, UCLA, ISBN 0962816221

- Grivel, Marianne, "Davent, Léon", Grove Art Online, Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, accessed January 6, 2017, subscription required

- Landau, David, in Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0300068832

- Reed, Sue Welsh, in: Reed, Sue Welsh & Wallace, Richard (eds), Italian Etchers of the Renaissance and Baroque, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1989, ISBN 0-87846-306-2 or 304-4 (pb)

Further reading

- Herbet, Félix: Les graveurs de l'École de Fontainebleau, B. M. Israël, Amsterdam, 1969.

- Zerner, Henri: École de Fontainebleau, Gravures, Arts et métiers graphiques, Paris, 1969.

- Grodecki, Catherine: in Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et de Renaissance, vol. XXXVI, 1974.