Kragujevac massacre

The Kragujevac massacre was the mass murder of between 2,778 and 2,794 mostly Serb men and boys in Kragujevac[lower-alpha 1] by German soldiers on 21 October 1941. It occurred in the German-occupied territory of Serbia during World War II, and came in reprisal for insurgent attacks in the Gornji Milanovac district that resulted in the deaths of 10 German soldiers and the wounding of 26 others. The number of hostages to be shot was calculated as a ratio of 100 hostages executed for every German soldier killed and 50 hostages executed for every German soldier wounded, a formula devised by Adolf Hitler with the intent of suppressing anti-Nazi resistance in Eastern Europe.

| Kragujevac massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II in Yugoslavia | |

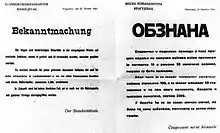

German troops registering people from Kragujevac and its surrounding areas prior to their execution | |

| Location | Kragujevac, German-occupied territory of Serbia |

| Date | 21 October 1941 |

| Target | Men and boys of Kragujevac and the surrounding district, mostly Serbs |

Attack type | Mass murder by shooting |

| Deaths | 2,778–2,794 |

| Perpetrators | Wehrmacht |

| Motive | Reprisal |

After a punitive operation was conducted in the surrounding villages, during which over 400 males were shot and four villages burned down, another 70 male Jews and communists who had been arrested in Kragujevac were killed. Simultaneously, males between the ages of 16 and 60, including high school students, were assembled by German troops and local collaborators, and the victims were selected from amongst them. The selected males were then marched to fields outside the city, shot with heavy machine guns, and their bodies buried in mass graves. Contemporary German military records indicate that 2,300 hostages were shot. After the war, inflated estimates ranged as high as 7,000 deaths, but German and Serbian scholars have now agreed on the figure of nearly 2,800 killed, including 144 high school students. As well as Serbs, massacre victims included Jews, Romani people, Muslims, Macedonians, Slovenes, and members of other nationalities.

Several senior German military officials were tried and convicted for their involvement in the reprisal shootings at the Nuremberg trials and the subsequent Nuremberg trials. The massacre had a profound effect on the course of the war in Yugoslavia. It exacerbated tensions between the two guerrilla movements, the communist-led Partisans and the royalist, Serbian nationalist Chetniks, and convinced Chetnik leader Draža Mihailović that further attacks against the Germans would only result in more Serb civilian deaths. The Germans soon found mass executions of Serbs to be ineffectual and counterproductive, as they tended to drive the population into the arms of insurgents. The ratio of 100 executions for one soldier killed and 50 executions for one soldier wounded was reduced by half in February 1943, and removed altogether later in the year. The massacre is commemorated by the October in Kragujevac Memorial Park and the co-located 21st October Museum, and has been the subject of several poems and feature films. The day the massacre took place is commemorated annually in Serbia as the Day of Remembrance of the Serbian Victims of World War II.

Background

Encirclement and invasion of Yugoslavia

Following the 1938 Anschluss between Nazi Germany and Austria, Yugoslavia came to share its northwestern border with Germany and fell under increasing pressure as its neighbours aligned themselves with the Axis powers. In April 1939, Italy opened a second frontier with Yugoslavia when it invaded and occupied neighbouring Albania.[1] At the outbreak of World War II, the Yugoslav government declared its neutrality.[2] Between September and November 1940, Hungary and Romania joined the Tripartite Pact, aligning themselves with the Axis, and Italy invaded Greece. Yugoslavia was by then almost completely surrounded by the Axis powers and their satellites, and its neutral stance toward the war became strained.[1] In late February 1941, Bulgaria joined the Pact. The following day, German troops entered Bulgaria from Romania, closing the ring around Yugoslavia.[3] Intending to secure his southern flank for the impending attack on the Soviet Union, German dictator Adolf Hitler began placing heavy pressure on Yugoslavia to join the Axis. On 25 March 1941, after some delay, the Yugoslav government conditionally signed the Pact. Two days later, a group of pro-Western, Serbian nationalist Royal Yugoslav Air Force officers deposed the country's regent, Prince Paul, in a bloodless coup d'état. They placed his teenage nephew Peter on the throne and brought to power a "government of national unity" led by the head of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force, General Dušan Simović.[4] The coup enraged Hitler, who immediately ordered the country's invasion, which commenced on 6 April 1941.[5]

Yugoslavia was quickly overwhelmed by the combined strength of the Axis powers and surrendered in less than two weeks. The government and royal family went into exile, and the country was occupied and dismembered by its neighbours. The German-occupied territory of Serbia was limited to the pre-Balkan War borders of the Kingdom of Serbia and was directly occupied by the Germans for the key rail and riverine transport routes that passed through it, as well as its valuable resources, particularly non-ferrous metals.[6] The occupied territory covered about 51,000 km2 (20,000 sq mi) and had a population of 3.8 million. Hitler had briefly considered erasing all existence of a Serbian state, but this was quickly abandoned and the Germans began searching for a Serb suitable to lead a puppet government in Belgrade.[7] They initially settled on Milan Aćimović, a staunch anti-communist who served as Yugoslavia's Minister of Internal Affairs in late 1939 and early 1940.[8]

Occupation and resistance

Two resistance movements emerged following the invasion: the communist-led, multi-ethnic Partisans, and the royalist, Serbian nationalist Chetniks, although during 1941, within the occupied territory, even the Partisans consisted almost entirely of Serbs. The Partisans were led by the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito; the Chetniks were led by Colonel Draža Mihailović, an officer in the interwar Royal Yugoslav Army. The two movements had widely divergent goals. Whereas the Partisans sought to turn Yugoslavia into a communist state under Tito's leadership, the Chetniks sought a return to the pre-war status quo, whereby the Yugoslav monarchy—and, by extension, Serb political hegemony—would be restored.[9] Communist resistance commenced in early July, shortly after the invasion of the Soviet Union, targeting both the Germans and the puppet authorities.[8] By late August 1941, the Partisans and Chetniks were carrying out joint attacks against the Germans.[9] The Partisans were well organised and many of their commanders had ample military experience, having fought in the Spanish Civil War. Within several months of the invasion, they had 8,000 fighters spread across 21 detachments in Serbia alone.[10] Many Chetniks were either veterans of the Balkan Wars and World War I or former members of the Royal Yugoslav Army.[11] They boasted around 20,000 fighters in the German-occupied territory of Serbia at the time of the massacre.[12]

On 29 August, the Germans replaced Aćimović with another fervent anti-communist, the former Minister of the Army and Navy and Chief of the General Staff, General Milan Nedić, who formed a new puppet government.[13] In September, the Nedić government was permitted to form the Serbian Volunteer Command (Serbo-Croatian: Srpska dobrovoljačka komanda; SDK), an auxiliary paramilitary formation to help quell anti-German resistance. In effect, the SDK was the military arm of the fascist Yugoslav National Movement (Serbo-Croatian: Združena borbena organizacija rada, Zbor), led by Dimitrije Ljotić.[14] It was originally intended to have a strength of 3,000–4,000 troops, but this number eventually rose to 12,000.[15] It was headed by Kosta Mušicki, a former colonel in the Royal Yugoslav Army, whom Nedić appointed on 6 October 1941.[16] In the early stages of the occupation, the SDK formed the bulk of Nedić's forces, which numbered around 20,000 men by late 1941.[17]

Prelude

Anti-German uprising

Nedić's inability to crush the Partisans and Chetniks prompted the Military Commander in Serbia to request German reinforcements from other parts of the continent.[17] In mid-September, they transferred the 125th Infantry Regiment from Greece and the 342nd Infantry Division from France to help put down the uprising in Serbia. On 16 September, Hitler issued Directive No. 312 to Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Wilhelm List, the Wehrmacht commander in Southeast Europe, ordering him to suppress all resistance in that part of the continent. That same day, the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht; OKW) issued Hitler's order on the suppression of "Communist Armed Resistance Movements in the Occupied Areas", signed by Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel.[18] This decree specified that all attacks against the Germans on the Eastern Front were to be "regarded as being of communist origin", and that 100 hostages were to be shot for every German soldier killed and 50 were to be shot for every German soldier wounded.[19][20] It was intended to apply to all of Eastern Europe, though an identical policy had already been implemented in Serbia as early as 28 April 1941, aimed at deterring guerrilla attacks. Attacks against the Germans increased in the first half of the year and Serbia once again became a war zone. German troops fanned through the countryside burning villages, taking hostages and establishing concentration camps. The first mass executions of hostages commenced in July.[20]

The strengthening of Germany's military presence in Serbia resulted in a new wave of mass executions and war crimes. The commanders who bore the most responsibility for these atrocities were primarily of Austrian origin and had served in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I.[21] Most were ardently anti-Serb, a prejudice that the historian Stevan K. Pavlowitch links to the Nazis' wider anti-Slavic racism.[22] On 19 September, General der Gebirgstruppe (Lieutenant General) Franz Böhme was appointed as Plenipotentiary Commanding General in Serbia, with direct responsibility for quelling the revolt, bringing with him the staff of XVIII Mountain Corps. He was allocated additional forces to assist him in doing so, reinforcing the three German occupation divisions already in the territory.[23] These divisions were the 704th Infantry Division, 714th Infantry Division and 717th Infantry Division.[24] Böhme boasted a profound hatred of Serbs and encouraged his predominantly Austrian-born troops to exact "vengeance" against them. His primary grievances were the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and subsequent Austro-Hungarian military defeats at the hands of the Royal Serbian Army, which he thought could only be rectified by the reprisal shooting of Serbian civilians. "Your objective," Böhme declared, "is to be achieved in a land where, in 1914, streams of German blood flowed because of the treachery of the Serbs, men and women. You are the avengers of those dead."[25]

Clashes at Gornji Milanovac

By late September 1941, the town of Gornji Milanovac had effectively been cut off from the rest of German-occupied Serbia by the frequent disruption of road and rail transport leading to and from it. On 29 September, elements of the Takovo Chetnik and Čačak Partisan detachments attacked Gornji Milanovac, which was defended by the 6th Company of the 920th Landesschützen (Local Defence) Battalion.[26] The 6th Company's garrison was based out of a local school. The guerrillas did not expect to capture the garrison, but undertook the attack in order to generate new recruits from the surrounding area. The local Chetnik commander, Zvonimir Vučković, became aware of the Partisan plans and decided to join in the attack to avoid the significant loss of prestige that would result from allowing the Partisans to attack alone. The insurgents launched a morning attack against the school. Although they were successful in overrunning the sentry posts, the Germans' heavy machine guns soon stopped the assault. In 90 minutes of fighting, ten Germans were killed and 26 wounded. The two insurgent groups judged that continuing the assault would be too costly and Vučković suggested negotiating with the Germans.[27] Knowing the Germans would be far more likely to carry out negotiations with royalists than with communists, the Partisans allowed the Chetniks to conduct the negotiating in order to lure the garrison out of the town.[28] A Chetnik envoy delivered an ultimatum to the garrison, demanding that it surrender to the guerrillas. The ultimatum was rejected.[26] Thirty minutes later, a second Chetnik envoy appeared, guaranteeing the 6th Company unmolested passage to Čačak on the condition that it left Gornji Milanovac the same day. He further requested that the town and its inhabitants be spared from any possible reprisals. The commander of the 6th Company agreed and evacuated the garrison. Around 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) outside Gornji Milanovac, the 6th Company was surrounded by the guerrillas and forced to surrender.[28][lower-alpha 2]

The 6th Company's disappearance caused unease in the German ranks. A reconnaissance flight was dispatched to locate it, to no avail.[28] The occupational authorities were unaware of the 6th Company's fate until a German officer escaped and informed them of what had transpired. He reported that the German prisoners were being humanely treated, but when Böhme became aware of the situation, he decided that retaliation was needed. He ordered the III. Battalion of the 749th Infantry Regiment to burn down Gornji Milanovac and take hostages in order to expedite the recovery of the captured German troops.[29] The III. Battalion started its advance on 5 October, fighting its way along the 40-kilometre (25 mi) road to Gornji Milanovac and sustaining casualties in the process. Upon entering Gornji Milanovac, it gathered between 120 and 170 male hostages, among them a Chetnik commander who had been scheduled to meet his superiors the following day. Hauptmann (Captain) Fiedler, the III. Battalion's commanding officer, hoped to use this man to contact the Chetnik command and organize a prisoner exchange. Fearing that such an action would jeopardize the recovery of the German prisoners, Fiedler decided not to raze Gornji Milanovac. Around this time, Fiedler received an SOS signal from nearby Rudnik, where another German unit was involved in heavy fighting with the guerrillas.[28] Fiedler decided to redirect the III. Battalion to Rudnik to relieve the unit. Assuming he would have to pass through Gornji Milanovac on his way back, he decided to postpone the taking of hostages in Gornji Milanovac and the razing of the town until his return from Rudnik. Contrary to Fiedler's expectations, the battalion was ordered back to Kragujevac immediately after relieving the unit at Rudnik, and was thus unable to raze Gornji Milanovac.[30] Böhme was furious, and on 15 October, he sent the III. Battalion back to Gornji Milanovac to carry out his original orders.[29] The battalion returned to Gornji Milanovac the same day, but now only forty people could be found to be taken as hostages. The town was then razed. This time, no attempt to exchange the hostages was made.[30]

Kraljevo massacre

On 15–16 October,[31] ten German soldiers were killed and 14 wounded during a joint Partisan-Chetnik attack on Kraljevo, a city about 150 kilometres (93 mi) south of Belgrade and 50 kilometres (31 mi) southeast of Gornji Milanovac.[32] On 15 October, troops of the 717th Infantry Division shot 300 civilians from Kraljevo in reprisal.[33] These reprisal killings continued over the following days, and by 17 or 20 October,[31][32] German troops had rounded up and shot 1,736 men and 19 "communist" women from the city and its outskirts,[34][35] despite attempts by local collaborationists to mitigate the punishment.[32] These executions were personally supervised by the commander of the 717th Infantry Division, Generalmajor (Brigadier General) Paul Hoffman.[36]

Timeline

Round-up

Kragujevac is an industrial city in Central Serbia, about 100 kilometres (62 mi) south of Belgrade,[37] and 37 kilometres (23 mi) east of Gornji Milanovac.[38] It had a population of more than 40,000 in 1941,[39] and was the headquarters of a German military district.[38] The city was also home to Yugoslavia's largest armaments factory, which had between 7,000 and 8,000 workers before the invasion.[40]

A report was written by the military district commander in Kragujevac, Hauptmann Otto von Bischofhausen, immediately after the massacre. This report was addressed to Böhme, and was later tendered in evidence at the Subsequent Nuremberg trials. According to von Bischofhausen, in the late evening of 18 October, all male Jews in Kragujevac, along with some communists, were arrested according to lists, totalling 70 persons. As this constituted far too few hostages to meet the quota of 2,300, it was proposed to collect the balance by arrests on the streets, squares and houses of Kragujevac, in an operation to be conducted by the III. Battalion of the 749th Infantry Regiment and the I. Battalion of the 724th Infantry Regiment, part of the 704th Infantry Division. In response to this proposal, von Bischofhausen claimed that he suggested to the garrison commander, Major Paul König, that instead of using the population of Kragujevac, the required hostages be gathered from surrounding villages which were known to be "completely strewn with communists".[41] According to von Bischofhausen's account, this suggestion was initially accepted by König, and on 19 October, the III. Battalion "mopped up" the villages of Mečkovac and Maršić and the I. Battalion conducted a similar operation in the villages of Grošnica and Milatovac. A total of 422 men were shot in these four villages, without any German losses.[42]

On the evening of 19 October, von Bischofhausen again met with König and was told that the original proposal was to be implemented the following day in order to collect the 2,300 hostages. The following evening, the male Jews and communists, who had been held without food since their arrest, were shot by German troops at the barracks and courtyard where they were being held.[38] Simultaneously, males between the ages of 16 and 60 were arrested within Kragujevac itself.[43][44] They were detained in the barracks of a former motorised battalion at Stanovija Field.[38] Over 7,000 hostages were assembled.[45] German troops and ethnic German units from the Banat were involved in the round-up,[12] as was the 5th Regiment of the SDK, under the command of Marisav Petrović.[14] According to von Bischofhausen, König permitted several classes of males to be excluded from the round-up, including those with a special pass issued by von Bischofhausen's district headquarters, members of a vital profession or trade, and those who were members of Ljotić's movement.[43][lower-alpha 3] When too few adult males could be located, high school students were also rounded up.[12] Also seized were priests and monks from the city's churches. Each hostage was registered and his belongings noted meticulously.[38]

Executions

The hostages were held overnight on a public plaza in the town. In his version of events, von Bischofhausen claimed that he made objections to König, but the latter insisted that his orders, which had been issued by the commander of the 749th Infantry Regiment, were to be carried out.[43] Shortly before the executions commenced, Ljotić obtained approval for two Zbor officials to scrutinise the hostages. Over 3,000 individuals, those identified as being "genuine nationalists" and "real patriots", were excluded from the execution lists as a result of Ljotić's intervention.[45] Those who were not extracted from the hostage pool were accused of being communists or spreading "communist propaganda". The Zbor officials told them they were not "worth saving" because they had "infected the younger generation with their leftist ideas."[46] The Germans considered Zbor's involvement to be a "nuisance". According to the social scientist Jovan Byford, it was never intended or likely to reduce the overall number of hostages killed in reprisal, and served only to ensure the exclusion of those that were deemed by Zbor to be worth saving.[45]

On the morning of 21 October, the assembled men and boys were marched to a field outside the town. Over a period of seven hours, they were lined up in groups of 50 to 120 and shot with heavy machine guns. "Go ahead and shoot", said an elderly teacher, "I am conducting my class".[12] He was shot together with his students.[44] As they faced the firing squad, many hostages sang the patriotic song Hey, Slavs, which became Yugoslavia's national anthem after the war.[47] One German soldier was shot for refusing to participate in the killings.[48] A German report stated: "The executions in Kragujevac occurred although there had been no attacks on members of the Wehrmacht in this city, for the reason that not enough hostages could be found elsewhere."[49][50] Even some German informants were inadvertently killed.[49] "Clearly", the Holocaust historian Mark Levene writes, "Germans in uniform were not that particular about who they shot in reprisal, especially in the Balkans, where the populace were deemed subhuman."[35]

Following the massacre, the Germans held a military parade through the city centre.[51] On 31 October, Böhme sent a report to the acting Wehrmacht commander in Southeast Europe, General der Pioniere (Lieutenant General) Walter Kuntze, reporting that 2,300 hostages had been shot in Kragujevac.[52]

Aftermath

Response

The Partisan commander and later historian Milovan Djilas recalled in his memoirs how the Kragujevac massacre gripped all of Serbia in "deathly horror".[53] Throughout the war, local collaborators pressured the Germans to implement stringent vetting procedures to ensure that "innocent civilians" were not executed, though only when the hostages were ethnic Serbs.[54][55] The scale of the massacres in Kragujevac and Kraljevo resulted in no quarter being given to German POWs by the guerrillas. "The enemy changed his attitude toward German prisoners," one senior Wehrmacht officer reported. "They are now usually being maltreated and shot."[53] By the time Böhme was relieved as Plenipotentiary Commanding General in December 1941, between 20,000 and 30,000 civilians had been killed in German reprisal shootings.[56] The ratio of 100 executions for each soldier killed and 50 executions for each soldier wounded was reduced by half in February 1943, and removed altogether later in the year. Henceforth, each individual execution had to be approved by Special Envoy Hermann Neubacher.[57] The massacres in Kragujevac and Kraljevo caused German military commanders in Serbia to question the efficacy of such killings, as they pushed thousands of Serbs into the hands of anti-German guerrillas. In Kraljevo, the entire Serbian workforce of an airplane factory producing armaments for the Germans was shot. This helped convince the OKW that arbitrary shootings of Serbs not only incurred a significant political cost but were also counterproductive.[58][59]

The killings at Kragujevac and Kraljevo exacerbated tensions between the Partisans and Chetniks.[32] They also convinced Mihailović that active resistance was futile for as long as the Germans held an unassailable military advantage in the Balkans, and that killing German troops would only result in the unnecessary deaths of tens of thousands of Serbs. He therefore decided to scale back Chetnik guerrilla attacks and wait for an Allied landing in the Balkans.[18][60][61] The killings occurred only a few days before Captain Bill Hudson, a Special Operations Executive officer, met with Mihailović at his Ravna Gora headquarters.[12] Hudson witnessed the aftermath of the massacre and noted the psychological toll it exacted. "Morning and night was the most desolating atmosphere," he recounted, "because the women were out in the fields, and every sunrise and sunset you would hear the wails. This had a very strong effect on Mihailović."[62] "The tragedy gave to Nedić convincing proof that the Serbs would be biologically exterminated if they were not submissive," Djilas wrote, "and to the Chetniks proof that the Partisans were prematurely provoking the Germans".[63] Mihailović's decision to refrain from attacking the Germans led to a rift with Tito and the Partisans. The Chetniks' non-resistance made it easier for the Germans to confront the Partisans, who for much of the remainder of the war could not defeat them in open combat.[64]

Legal proceedings and casualty estimates

On 11 November 1941, the Partisans captured Major Renner, the area commander in Leskovac, who was taking part in an anti-Partisan sweep around Lebane. Mistaking him for König, who by some accounts had given Renner a cigarette case engraved with his name, the Partisans executed Renner as a war criminal. For almost fifty years, it was widely believed that König, and not Renner, had been killed by the Partisans. In 1952, a plaque was erected at the place where König was purported to have been killed, and a song was written about the incident. In the 1980s, it was conclusively proven that the German officer executed by the Partisans in November 1941 was not König. A new plaque was thus dedicated in 1990.[65]

List and Böhme were both captured at the end of the war. On 10 May 1947, they were charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity as part of the Hostages Trial of the subsequent Nuremberg trials.[66] One of the crimes specifically listed in Count 1 of the indictment was the massacre of 2,300 hostages in Kragujevac.[67] Böhme committed suicide before his arraignment.[66] List was found guilty on Count 1, as well as on another count.[68] He was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1948,[69] but was released due to ill health in 1953. Despite this, he lived until June 1971.[70] Keitel was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials, and subsequently hanged.[71] Hoffmann, whom the local population dubbed the "butcher of Kraljevo and Kragujevac", was promoted to command the more capable 352nd Infantry Division in November 1941.[72] He ended the war as the commander of a prisoner-of-war camp, having been demoted for refusing to shoot deserters in the Ukraine.[36] The 717th Infantry Division was reorganised as the 117th Jäger Division later in the war and its troops took part in the massacre of hundreds of Greek civilians at Kalavryta in December 1943.[58]

At least 31 mass graves were discovered in Kragujevac and its surroundings after the war.[73] In 1969, the historian Jozo Tomasevich wrote that, despite German official sources stating 2,300 hostages had been shot, both the Partisans and Chetniks had agreed that the number of victims was about 7,000. He further stated that careful investigation by the scholar Jovan Marjanović in 1967 had put the figure at about 5,000.[49] In 1975, Tomasevich noted that some estimates of the number of those killed were as high as 7,000, but that the foremost authority on German terror in Serbia, Venceslav Glišić, placed the figure at about 3,000.[34] In 2007, Pavlowitch wrote that inflated figures of 6,000–7,000 victims were advanced and widely believed for many years, but that German and Serbian scholars had recently agreed on the figure of 2,778.[74] In the same year, the curator of the 21st October Museum at Kragujevac, Staniša Brkić, published a book listing the names and personal data of 2,794 victims.[75] Of the total killed, 144 were high school students, and five of the victims were 12 years old.[51] The last living survivor of the massacre, Dragoljub Jovanović, died in October 2018 at the age of 94. He survived despite sustaining eleven bullet wounds and had to have one of his legs amputated. After the war, he was appointed the inaugural director of the 21st October Museum.[76]

Legacy

The massacre at Kragujevac came to symbolise the brutality of the German occupation in Yugoslav popular memory.[77] It has drawn comparisons to the Germans' destruction of the Czechoslovak village of Lidice in June 1942 and the massacre of the inhabitants of Oradour-sur-Glane, in France, in June 1944.[44] To commemorate the victims of the Kragujevac massacre, the whole of Šumarice, where the killings took place, was designated a memorial park in 1953. It is now known as the October in Kragujevac Memorial Park, and covers 353 hectares (870 acres) encompassing the area that contains the mass graves. The 21st October Museum was founded within the park on 15 February 1976. There are also several monuments within the park, including the Interrupted Flight monument to the murdered high school students and their teachers, and the monuments Pain and Defiance, One Hundred for One, and Resistance and Freedom. The Memorial Park website notes that the victims of the massacre included Serbs, Jews, Romani people, Muslims, Macedonians, Slovenes and members of other nationalities.[78] The memorial was damaged during the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999.[79]

The Serbian poet and writer Desanka Maksimović wrote a poem about the massacre titled Krvava bajka ("A Bloody Fairy Tale").[80] The poem was later included in the Yugoslav secondary school curriculum and schoolchildren were required to memorise it.[81] It ranks among the most famous Serbian-language poems.[82] In 1965, the Belgian poet Karel Jonckheere wrote the poem Kinderen met krekelstem ("Children with Cricket Voices"), also about the massacre.[83] The Blue Butterfly, a book of poetry by Richard Berengarten, is based on the poet's experiences while visiting Kragujevac in 1985, when a blue butterfly landed on his hand at the entrance to the memorial museum.[84]

The massacre has been the subject of two feature films: Prozvan je i V-3 (V-3 is Called Out; 1962)[85] and Krvava bajka (A Bloody Fairy Tale; 1969), named after the eponymous poem.[86] In 2012, the National Assembly of Serbia passed a law declaring 21 October a public holiday, the Day of Remembrance of the Serbian Victims of World War II.[87]

See also

Notes

- Serbian Cyrillic: Крагујевац, pronounced [krǎɡujeʋat͡s] (

listen)

listen) - The material spoils were divided evenly between the Chetniks and the Partisans, while all 62 prisoners of war (POWs) went to the Chetniks. The POWs were put to work clearing rubble in Čačak over the next several days. They were then dispatched to Ravna Gora and later to Požega.[28]

- Those excluded on the basis of their profession included medical personnel, pharmacists and technicians.[44]

Footnotes

- Roberts 1973, pp. 6–7.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 8.

- Roberts 1973, p. 12.

- Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 10–13.

- Roberts 1973, p. 15.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 49.

- Ramet & Lazić 2011, pp. 19–20.

- Tomasevich 2001, pp. 177–178.

- Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 59–60.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 198.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 118–123.

- Lampe 2000, p. 217.

- Ramet & Lazić 2011, p. 22.

- Cohen 1996, p. 38.

- Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 58–59.

- Cohen 1996, p. 37.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 28.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 146.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 140.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 61.

- Lampe 2000, p. 215.

- Pavlowitch 2007, pp. 60–61.

- Tomasevich 1975, pp. 97–98.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 96.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 199.

- Trifković 2020, p. 35.

- Glenny 2001, pp. 491–492.

- Trifković 2020, p. 36.

- Manoschek 1995, pp. 158–159.

- Trifković 2020, p. 37.

- Browning 2007, p. 343.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 62.

- Shepherd 2012, p. 306, note 109.

- Tomasevich 1975, p. 146, note 92.

- Levene 2013, p. 84.

- Shepherd 2012, p. 140.

- Mazower 2002, p. 7.

- Glenny 2001, p. 492.

- Jorgić 2013, p. 79.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 624.

- von Bischofhausen 1950, p. 981.

- von Bischofhausen 1950, pp. 981–982.

- von Bischofhausen 1950, p. 982.

- Prusin 2017, p. 97.

- Byford 2011a, pp. 126–127, note 35.

- Antić 2012, p. 29.

- Pavković & Kelen 2016, p. 56.

- West 1995, p. 112.

- Tomasevich 1969, p. 370, note 74.

- Singleton 1985, p. 194.

- Glenny 2001, p. 493.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals 1950, pp. 767 & 1277.

- Trifković 2020, p. 41.

- Byford 2011a, p. 306.

- Byford 2011b, p. 120.

- Manoschek 2000, p. 178.

- Tomasevich 2001, p. 69.

- Mazower 2004, p. 154.

- Browning 2007, p. 344.

- Milazzo 1975, p. 31.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 63.

- Williams 2003, p. 61.

- Mazower 2008, p. 483.

- Shepherd 2016, p. 200.

- Trifković 2020, p. 42.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals 1950, p. 759.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals 1950, p. 767.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals 1950, p. 1274.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals 1950, p. 1318.

- Wistrich 2013, p. 159.

- Wistrich 2013, p. 137.

- Browning 1985, p. 100, note 86.

- Glenny 2001, pp. 492–493.

- Pavlowitch 2007, p. 62, note 15.

- Markovich 2014, p. 139, note 17.

- Radio Television of Serbia 22 October 2018.

- Benz 2006, p. 206.

- Memorial Park 2017.

- Winstone 2010, p. 408.

- Hawkesworth 2000, p. 209.

- Milojković-Djurić 1997, p. 106, note 5.

- Juraga 2002, p. 204.

- Bourgeois 1970, p. 68.

- Derrick 2015, pp. 170–171.

- Daković 2010, p. 393.

- Liehm & Liehm 1977, p. 431.

- Radio Television of Serbia 21 October 2012.

References

- Antić, Ana (2012). "Police Force Under Occupation: Serbian State Guard and Volunteers' Corps in the Holocaust". In Horowitz, Sara R. (ed.). Back to the Sources: Re-examining Perpetrators, Victims and Bystanders. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. pp. 13–36. ISBN 978-0-8101-2862-0.

- Benz, Wolfgang (2006). A Concise History of the Third Reich. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23489-5.

- von Bischofhausen, Otto (1950) [1941]. "The Hostage Case". Report to Commanding Officer in Serbia, 20 October 1941 Concerning Severe Reprisal Measures (PDF). Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals. Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany: Nuremberg Military Tribunals. OCLC 312464743.

- Bourgeois, Pierre (1970). Quart de siècle de poésie française de Belgique [A Quarter of a Century of French Poetry from Belgium] (in French). Brussels, Belgium: A. Manteau. OCLC 613760355.

- Browning, Christopher R. (1985). Fateful Months: Essays on the Emergence of the Final Solution. New York City: Holmes & Meier. ISBN 978-0-8419-0967-0.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2007). The Origins Of The Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939 – March 1942. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0392-1.

- Byford, Jovan (2011a), "The Collaborationist Administration and the Treatment of the Jews in Nazi-occupied Serbia", in Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola (eds.), Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two, London, England: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 109–127, ISBN 978-0-230-27830-1

- Byford, Jovan (2011b). "Willing Bystanders: Dimitrije Ljotić, "Shield Collaboration" and the Destruction of Serbia's Jews". In Haynes, Rebecca; Rady, Martyn (eds.). In the Shadow of Hitler: Personalities of the Right in Central and Eastern Europe. London, England: I.B. Tauris. pp. 295–312. ISBN 978-1-84511-697-2.

- Cohen, Philip J. (1996). Serbia's Secret War: Propaganda and the Deceit of History. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-760-7.

- Daković, Nevena (2010). "Love, Magic and Life: Gypsies in Yugoslav Cinema". In Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (eds.). Junctures and Disjunctures in the 19th and 20th Centuries: Types and Stereotypes. History of the Literary Cultures of East–Central Europe. 4. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 391–402. ISBN 978-90-272-3458-2.

- Derrick, Paul Scott (2015). Lines of Thought: 1983–2015. Valencia, Spain: University of Valencia. ISBN 978-84-370-9951-4.

- Glenny, Misha (2001). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. London, England: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-023377-3.

- Hawkesworth, Celia (2000). Voices in the Shadows: Women and Verbal Art in Serbia and Bosnia. Budapest, Hungary: Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9116-62-7.

- "History of the October in Kragujevac Memorial Park". October in Kragujevac Memorial Park. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Jorgić, Kristina (2013). "The Kragujevac Massacres and the Jewish Persecution of October 1941". Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 27 (1): 79–82. doi:10.1353/ser.2013.0010. ISSN 0742-3330.

- Juraga, Dubravka (2002) [2000]. "Maksimović, Desanka". In Willhardt, Mark; Parker, Alan Michael (eds.). Who's Who in Twentieth-Century World Poetry. London, England: Routledge. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-41516-356-9.

- Lampe, John R. (2000) [1996]. Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country (2nd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Levene, Mark (2013). Annihilation: The European Rimlands, 1939–1953. The Crisis of Genocide. 2. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-150555-3.

- Liehm, Mira; Liehm, Antonín J. (1977). The Most Important Art: Eastern European Film After 1945. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03157-9.

- Manoschek, Walter (1995). "Serbien ist judenfrei": militärische Besatzungspolitik und Judenvernichtung in Serbien 1941/42 ["Serbia is free of Jews": Military Occupation Policy and Extermination of Jews in Serbia 1941/42] (in German). Munich, Germany: Oldenbourg Verlag. ISBN 978-3-486-56137-1.

- Manoschek, Walter (2000). "The Extermination of the Jews in Serbia". In Herbert, Ulrich (ed.). National Socialist Extermination Policies: Contemporary German Perspectives and Controversies. New York City: Berghahn Books. pp. 163–186. ISBN 978-1-57181-751-8.

- Markovich, Slobodan G. (2014). "Memories of Victimhood in Serbia and Croatia from the 1980s to the Disintegration of Yugoslavia". In El-Affendi, Abdelwahab (ed.). Genocidal Nightmares: Narratives of Insecurity and the Logic of Mass Atrocities. New York City: Bloomsbury. pp. 117–141. ISBN 978-1-62892-073-4.

- Mazower, Mark (2002). The Balkans: A Short History. New York City: Random House. ISBN 978-0-8129-6621-3.

- Mazower, Mark (2004). "Military Violence and the National Socialist Consensus: The Wehrmacht in Greece, 1941–44". In Heer, Hannes; Naumann, Klaus (eds.). War of Extermination: The German Military in World War II. New York City: Berghahn Books. pp. 146–174. ISBN 978-1-57181-493-7.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London, England: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9681-4.

- Milazzo, Matteo J. (1975). The Chetnik Movement & the Yugoslav Resistance. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-1589-8.

- Milojković-Djurić, Jelena (1997). "Serbian Poetry and Pictorial Representations of the Holocaust" (PDF). Journal of the North American Society for Serbian Studies. Bloomington, Indiana: Slavica Publishers. 11 (2): 96–107. ISSN 0742-3330. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2016.

- Nuremberg Military Tribunals (1950). "The Hostage Case". Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals (PDF). 11. Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany: Nuremberg Military Tribunals. OCLC 312464743.

- Pavković, Aleksandar; Kelen, Christopher (2016). Anthems and the Making of Nation States: Identity and Nationalism in the Balkans. London, England: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-969-8.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2007). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-85065-895-5.

- Prusin, Alexander (2017). Serbia Under the Swastika: A World War II Occupation. Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-25209-961-8.

- Radio Television of Serbia (21 October 2012). "Dosta su svetu jedne Šumarice" [One Šumarice is Enough] (in Serbian). Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Radio Television of Serbia (22 October 2018). "Preminuo poslednji đak koji je preživeo streljanje u Šumaricama" [The Last Surviving Victim of the Šumarice Executions Has Die] (in Serbian). Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- Ramet, Sabrina P.; Lazić, Sladjana (2011). "The Collaborationist Regime of Milan Nedić". In Ramet, Sabrina P.; Listhaug, Ola (eds.). Serbia and the Serbs in World War Two. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–42. ISBN 978-0-230-34781-6.

- Roberts, Walter R. (1973). Tito, Mihailović and the Allies 1941–1945. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0773-0.

- Shepherd, Ben (2012). Terror in the Balkans: German Armies and Partisan Warfare. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04891-1.

- Shepherd, Ben H. (2016). Hitler's Soldiers: The German Army in the Third Reich. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17903-3.

- Singleton, Frederick Bernard (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. New York City: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27485-2.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1969). "Yugoslavia During the Second World War". In Vucinich, Wayne S. (ed.). Contemporary Yugoslavia: Twenty Years of Socialist Experiment. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. pp. 59–118. OCLC 652337606.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (1975). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: The Chetniks. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0857-9.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3615-2.

- Trifković, Gaj (2020). Parleying with the Devil: Prisoner Exchange in Yugoslavia, 1941‒1945. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-1-94966-810-0.

- West, Richard (1995). Tito and the Rise and Fall of Yugoslavia. New York City: Caroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-0191-9.

- Williams, Heather (2003). Parachutes, Patriots and Partisans: The Special Operations Executive and Yugoslavia, 1941–1945. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-19494-9.

- Winstone, Martin (2010). The Holocaust Sites of Europe: An Historical Guide. London, England: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85773-028-2.

- Wistrich, Robert S. (2013). Who's Who in Nazi Germany. Cambridge, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-41381-0.