Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum

Khnumhotep (Ancient Egyptian: ẖnm.w-ḥtp(.w))[1] and Niankhkhnum (Ancient Egyptian: nj-ꜥnḫ-ẖnm.w)[2] were ancient Egyptian royal servants. They shared the title of Overseer of the Manicurists in the Palace of King Nyuserre Ini, sixth pharaoh of the Fifth Dynasty, reigning during the second half of the 25th century BC. They were buried together at Saqqara and are listed as "royal confidants" in their joint tomb.[3]:98 They are notable for their unusual depiction in Egyptian records, often interpreted as the first recorded same-sex couple,[4]:96ff[5]:200-201 a claim that has met considerable debate.

Family

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum are believed by Thomas Dowson, Greg Reeder, and some other scholars to be the first recorded same-sex couple in ancient history. [4]:96ff[5]:200-201 The assumed romantic relationship between Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum is based on depictions of the two men standing nose to nose and embracing.[6][7] Niankhkhnum's wife, depicted in a banquet scene, was almost completely erased in antiquity, and in other pictures Khnumhotep occupies the position usually designated for a wife. Their official titles were "Overseers of the Manicurists of the Palace of the King" (see sections Titularies, Banquets and music). Critics argue that both men appear with their respective wives and children, suggesting the men were brothers, rather than lovers.[8]:22[9]:88

Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum are depicted in the tomb with their respective families. It has been proposed that they were the sons of Khabaw-khufu and Rewedzawes. They appear to have had three brothers named Titi, Nefernisut, and Kahersetef. Three possible sisters are also attested. They are named Neferhotep-hewetherew, Mehewet and Ptah-heseten. Niankhkhnum's wife was named Khentikawes. The couple appear in the tomb with three sons named Hem-re, Qed-unas and Khnumhezewef, and three daughters, Hemet-re, Khewiten-re and Nebet. At least one grandson is attested, Irin-akheti, the son of Hem-re and his wife, Tjeset.

Khnumhotep had a wife by the name of Khenut. Khnumhotep and Khenut had at least five sons named Ptahshepses, Ptahneferkhu, Kaizebi, Khnumheswef and Niankhkhnum the younger (possibly named after the tomb owner), as well as a daughter named Rewedzawes.[8]:55-61

Careers

Egyptian records note Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum as the heads manicurists for the royal family, but they may have held a number of different official titles and duties

Bureaucrats

On duty at the sun temple, Niankhkhnum or Khnumhotep may have watched over subordinate officials, such as the m-r pr Sna "overseer of the magazines" who in turn supervised crews of porters stocking and withdrawing material from the granaries and store-rooms

Manicurists, hairdressers, and adorners

Care of the king's body and wardrobe in preparation for his public appearances required a large number of aides, apparently working in different ateliers each under its own leadership. In addition to the manicurists whom Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep supervised (discussed in the titulary section of this article), the palace had attendants under one or more men holding the title jrj nfr HAt "keeper of the headdress," responsible for the king's wigs and headcloths, jrw Snj " hairdressers,[11]:189 who kept him shaven, and an m-r n jzwj Xkrwt nswt "overseer of the two chambers of king's adorners."[12]:74 The post of Xkrt nswt "adorner of the king" was always held by women, who were legally, if not socially, equal to men in Egypt.[13]:8 Neferhotep-Hathor is labeled with this status at the funeral procession of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep.[14]:Szene 12

How, or how often, personnel in the hairdressers' shop, which from titulary evidence stands higher than the manicurists in 5th and 6th Dynasty prestige rankings, communicated with the latter remains unknown. No hairdressers are labeled at the funeral procession. Ptahshepses, the keeper of the headdress who became Nyussere's vizier,[12]:73 and Ti, overseer of the pyramids and sun temples, are two officials whom Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep may have worked with. Both Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum are attested on a harvest scene in the splendid burial estate of Ptahshepses, where they may have been quarry supervisors, yet named as jr ant pr aA "palace manicurists," quite junior to titulary in their own tomb, which could mean Ptahshepses died while they were younger.[15]:469 A door jamb, besides TAtj "vizier," displays the title HAt-a "one whose arm is in front," a pure honorific Allen distinguishes from the m-r and jrj titles specifying responsibility domains we've encountered up to now. The jrj nfr HAt "keeper of the headdress" epithet, recorded in many of the rooms, is spelled with the mouth sign (Gardiner D21), not the eye sign (D4), so that it shares the introductory word of jrj-pat "hereditary prince," another of Allen's honorifics.[11]:178[16]:34

The tomb

The tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum was discovered by Egyptologist Ahmed Moussa in the necropolis at Saqqara, Egypt in 1964, during the excavation of the causeway for the pyramid of King Unas.[3]:98 It is the only tomb in the necropolis where men are displayed embracing and holding hands. In addition, the men's chosen names (both theophorics to the creator-god Khnum) form a linguistic reference to their closeness: Niankhkhnum means "life belongs to Khnum" and Khnumhotep means "Khnum is satisfied;"[18] The precise king and regnal date of this tomb are unknown; style places it in the latter 5th Dynasty under Nyuserre or Menkauhor. No human remains were discovered inside.[10]:644 It is believed the tomb was built in stages, first a sequence of two chambers cut into the limestone of a low escarpment in the northern area of Saqqara, then a surface-built mastaba structure added to mate with the earlier construction. This would have occurred as the two intended occupants gained resources.

In a banquet scene, Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep are entertained by dancers, clappers, musicians and singers; in another, they oversee their funeral preparations. In the most striking portrayal, the two embrace, noses touching, in the most intimate pose allowed by canonical Egyptian art, surrounded by what would appear to be their heirs.

Titularies

Egyptian tombs feature lists of titles and epithets honoring the deceased or held during life, often giving titles for other persons who appear on a wall. For Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, the titulary may be condensed as follows:[14][note 1][note 2][note 3]

.svg.png.webp)

Held by either or both men:

- m-r jr ant pr aA "overseer of manicurists (literally, 'those who do fingernails') in the palace." pr aA means "the great house,"[16]:34 the name for the center of power, at Memphis during the Old Kingdom. In the later story of Sinuhe, after 12th Dynasty rulers of the Middle Kingdom had fixed the political capital near the Fayum Oasis at Itjtawy, the palace was called the Xnw "interior."[14]:Szene 13[19]:59

- sHD jr ant pr aA "inspector of manicurists in the palace"[14]:Szene 15[11]:1179

- Hrj sStA "guardian of secrets" (As a verb, sStA is causative, so the term would refer to the process of making secrets. For more on this title, which originates from the Giza necropolis, see subsection on Hrj sStA below or consult the reference.)[12]:75[14]:Szene 13

- rx nswt "king's acquaintance"[14]:Szenen 1.2, 1.3

- zXAw nswt "king's scribe"

- mHnk nswt "confidant of the king"[14]:Szene 13, 15

- jr xt nswt "keeper of the king's things"[14]:Szene 23

- mrr nb.f "one who is beloved of his lord"[8]:Plates 90, 92

- Hm-nTr ra m Szp jb ra "sun priest in the (place where the sun-god) Ra's heart receives welcome," that is, in Nyuserre's solar temple at Abu Ghurab[11]:808[14]:Szene 23

- wab mn swt nj-wsr-ra "purity attendant of the enduring places of Nyuserre" (a cleaner-priest in this king's pyramid complex at Abusir). A peculiar hieroglyphic grapheme in this title, a device of three seat signs (denoting plural noun) followed by a pyramid, is seen on a gold seal purportedly found in Turkey, a demonstration of official use of a pyramid establishment title for signing documents.[14]:Szene 23,[20]

- wab nswt "one who purifies the king." (a personal priest to the king)[14]:Szene 13

- nb jmAx nTr aA "lord of those who are honored before the great god" (an aspirational title signifying donations to the individual's mortuary estate from the king; see subsection on jmAx below)[14]:Szene 13

The Hrj sStA and control of information by the state

The title Hrj sStA "keeper of the secrets" is attested for 13 individuals during the Old Kingdom, at least once elaborated to the form Hr sStA mdw-nTr "keeper of the secrets of the god's words," meaning the hieroglyphic language used on monuments.[12]:75[16]:44 In contrast with the hieratic script used for everyday record-keeping, already an elite activity, the content of hieroglyphic texts was closely controlled property of the state and permission from the king was probably required for inscriptions in one's tomb, as we see in a royal authorization for Rawer, an official under Neferirkare buried at Giza, to do so.

The jmAx concept as proximity to king and god, in life and hereafter

jmAx xr nTr aA "honored one near the great god" is a euphemism for "dead," appearing frequently in tombs and on slab stelae, even though it, like the word (and goddess) mAat, evokes a multifarious idealization of relationships between social and cosmological ranks.

Epithets beginning with jmAx are common throughout Egyptian history from the 4th Dynasty on,[21]:194 tending toward greater specificity in later periods. An official or family member could possess several, both jmAx xr nTr aA "honored before the great god" (when dead)[14]:Szene 34 and jmAx xr nswt "honored before the king" (presumably in life).[14]:Szenen 13 It is important to realize that king and god themselves can be one and the same, especially upon death, as Amenemhat I would be in the early Middle Kingdom story of Sinuhe.[19]:59 The goal of kingship, after maintaining social order (mAat) in Egypt, was to ascend and unite with the sun disk of Heliopolitan theology, maintained from Old Kingdom until the arrival of Christianity.[16]:121[22]:141Since jmAx can also be translated as "provided for," the connection an official's tomb holds with royal subsidy is made implicit; although officials built their tombs using mainly their own resources once the 4th Dynasty (and Khufu's largess at Giza) ended.[23]:103[24]:14

Forecourt entrance with architrave and pillars

A two-pillared portico makes up the eastern half of the mastaba's façade. The front is inscribed with Niankhkhnum depicted on the left, Khnumhotep on the right. These two reliefs are virtually identical, only the names being different.

Interior of forecourt

This space is fairly small. The west side is decorated with a funerary procession for Niankhkhnum and the east side shows a matching funerary procession for Khnumhotep.

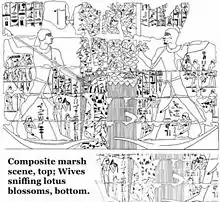

The uppermost south wall shows the two men seated before an offering table. Niankhkhnum is seated on the right, while Khnumhotep is seated on the left. The table with offerings stretches out between them. Below the offering scene the two men are depicted netting fowl and fishing. On the left, below this lintel, Khnumhotep stands on a papyrus boat, spearing fish in the water that floods the bases of papyrus stalks he drifts among. He is accompanied by his wife Khenut, sons and a daughter. On the right, Niankhkhnum is depicted in a similar manner, aiming his throw stick at the waterfowl although the active arm is now missing from this piece.

Outer vestibule

At the entrance scenes of baking bread and brewing beer are depicted. Barley is carefully measured out and turned into bread. Other scenes include goat herding, ship building, harvesting scenes, sailing, netting of birds, etc. The east wall contains a legal text. Below this text several people are depicted thought to be the family of the two men. At the very bottom ships are shown. The men are shown standing before the main cabin of the ship.[10]

Court (open to sky)

An undecorated space which serves to connect the vestibule and chambers on the north end of the mastaba with the abutting rock-cut sections of the tomb to their south. Modern security grates now obstruct much of the full sun that would have flooded this small, walled yard, yet little or no sun fell on the vestibule to the outer rock-cut hall described below, as its entrance faces north.[10]

Inner vestibule

With names, titles, and standing portraits of the two men, it is much smaller than the other vestibule and without pillars. The lintel's inside surface features another cattle count scene, and each tomb owner appears on one of the side walls with his wife, amid a flow of yet more offerings from the herds.[10]

Outer hall

This outer hall, an antechamber to the final, inner hall, marks the tomb's first, rock-cut phase of construction, and is fully decorated. Before the mastaba was added, it would have been the first room a visitor entered after passing through the forecourt, which was relocated northeast to the far side of the mastaba where it is now. Here, people engage in agricultural occupations including the weighing of corn and grain, the ploughing of fields, and harvesting.

A double doorway to the inner hall is on the west wall, with a broad pillar dividing the doors. Its surface depicts the two men, their children, drawn much smaller to reflect a lesser status, in tow behind each parent.[10] The respective wives do not appear in this scene. Niankhkhnum has three sons and three daughters, Khnumhotep five sons and one daughter, some of whom may be adopted or conceived by a second wife or mistress as they lack the shendyt kilts worn by the others. All the children except Niankhkhnum's youngest son, who still runs naked with his shaved head bearing the single sidelock of youth, are adults despite the scale they are drawn at.[26]:38 Ptahshepses, a son of Khnumhotep, wore the youth sidelock in the marsh scene of the forecourt but not so here. Either inconsistency intrudes, or the art, completed over years, reflects some changes of status which transpire during the tomb's construction.

Inner hall

Now on the reverse side of the dividing pillar, Niankhknum and Khnumhotep embrace again, and a third time on the opposite wall of this small chamber. They are without their children in this innermost sanctuary. Each man has a "false door," a carved, slot-like niche surrounded by inscriptions which was produced in the royal workshops and installed in the tomb. Niankhknum's is seriously damaged.[10] The false door provided an accessway for the deceased, as a spiritual being, to reach offerings left at the tomb by the living. These offerings were to be set on plinths in front of the false doors.[22]:155-159[27]:19, 55 Behind the false doors is a small statue closet known as the serdab. A statue of each man would have been placed here, facing the chamber as if to watch visitors come and go, but invisible to the offering-bringers since the false doors are actually solid. It appears that tomb robbers removed the statues in antiquity; they are no longer extant.[28]:31[10]:644

Banquets and music

%252C_detail_from_stela_of_Nefret-iabet_below%252C_Old_Kingdom%252C_ancient_Egypt.jpg.webp)

The banquet scene (first image)[10]:643 shows Niankhkhnum clean-shaven (left) and Khnumhotep (wearing a short beard) seated facing one another across comestibles spread between, each with his own breadboard table. Set off by a baseline, this is read separately from the two registers of entertainment below them.[32]:148-149 A different upper register substitutes in the contemporary Saqqara tomb of Ti (next image), where no food is present with the owner, who is seated holding a scepter, his wife (drawn at half-scale) by his feet.

Funeral procession

Longevity and circumstances of the tomb owners' deaths are unknown. The limestone sarcophagi beneath the mastaba were ransacked and wooden coffins of later date interred in the burial chambers. Booth, citing others, adheres to the theory that Khnumhotep died first, leaving Niankhkhnum to complete the tomb's art. This conclusion was drawn from Khnumhotep's jmAx epithets (see Titulary section), a style of beard he wears, and exclusion of his wife at the banquet scene when Niankhknum's was originally there.[33]:ch.5 at n.92

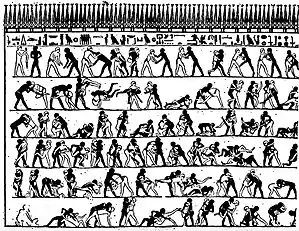

The mourners and relatives

Four of the rows show people walking in single file. Familial relationships stay unclear in Egyptian tombs: Only the pictures of wives (Hmt.f "his wife"), daughters (zAt.f), and sons (zA.f) bore genealogical notations. Reeder identifies Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep themselves at the rear of Khabau-Khufu's line; he and the woman behind him are Niankhkhnum's parents. This woman and Khnumhotep are the only paraders who do not place their left hands upon their hearts, but use them to hold the hand or arm of the person in front of them, suggesting a degree of intimacy between them and the persons they grasp (Khabau-Khufu or Niankhkhnum, respectively).[5]:197 More of the deceased's children plus some of foggier status appear, including Ankhredwi-nesut, police captain Khnumhezuf, palace manicurist Kasetef, and Hemre's wife Tjeset.[14]:Szene 12[note 4] Sekhem, a scribe of the pr HD "white house," is both here and behind Niankhkhnum in the forecourt marsh scene, where he had a namesake on Khnumhotep's side, albeit with additional post of inspector of Hm-kA priests marked.

In Reeder's interpretation, absence of Khnumhotep's parents here matching absence of his wife at the banquet, is consistent with Khnumhotep predeceasing his afterlife roommate. Other officials in line and in the next register (where figures are smaller) include supervisors of weavers, manicurists, Hm-kA priests, and scribes.[14]:Szene 12{{r|group=note|note10. Uncertain precise relationship connects Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep as well; Altenmüller considers them brothers, Baines that they were twins, and Reeder that they were same-sex conjugal or domestic partners evidenced by iconography normally used for husband and wife, or, with Khnumhotep, for women (sniffing the lotus blossom).

See also

Notes

- After registration, must search for pages on Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Click picture on home page to enter site. Pick "navigating the hierarchical tree of objects and texts" on the database search page. Position of texts in the hierarchical tree is *Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, *Strukturen und Transformationen Berlin-Brandenburgische, *Grabinschriften des Alten Reiches, *Sakkara, *Unas-Friedhof, *Mastaba des Nianch-Chnum und Chnum-hotep. Be sure to click on the nodes themselves, at left on each line.

- Wall texts in Thes. Ling. Aeg. identified by Porter & Moss : Szenen 1.2 and 1.3 [Porter & Moss III, p. 641, I 1(c-d)]; Szene 12 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 8]; Szene 13 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 9]; Szene 15 [Porter & Moss III, p. 642, II 9]; Szene 23 [Porter & Moss III, p. 643, IV 15]; Szene 31 [Porter & Moss III, p. 643, V 20].

- To avoid display problems, the MDC system is used here to transliterate Egyptian words, hence note that A and a are different. The complete set of consonantal “letters” (in lexical order for consulting an Egyptian dictionary) are A, j, y, a, w, b, p, f, m, n, r, h, H, x, X, z, s, S, q, k, g, t, T, d, D, set apart in italics. Other systems exist with special fonts; the A looks like 3 and the a like ‘ in books using these. (Wikipedia list here).

- Perhaps "guard" should be compared with "police" in this context, showing the danger of modern terminology in translation. Police in ancient Egypt, unlike ordinary door guards, most likely did gather personal intelligence and search for wanted persons. However, they protected only the state; as a rule, they did not investigate crimes against citizens. The revenge system, or a lawsuit if the victims could afford to pursue it, were the only redresses available for crimes that did not involve state officials or property. See Eyre, C. (2013), The Use of Documents in Pharaonic Egypt, Oxford, pp. 178, 307-308 for administrative papyri used in the prosecution of Ramesside-era tomb robbers. See again Eyre, C. (1984), "Crime and Adultery in Ancient Egypt," Jl. of Egyptian Archaeology 70, pp. 92-105 for a general discussion of how Egypt handled antisocial behavior, esp. pp. 92-94 where the corruption case of Paneb arises. Resort to New Kingdom evidence is due to so little surviving from the Old Kingdom. 5th Dynasty police agencies were probably less evolved, deploying fewer personnel.

References

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen (PDF). Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 276. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Ranke, Hermann (1935). Die Ägyptischen Personennamen, Bd. 1: Verzeichnis der Namen. Glückstadt: J.J. Augustin. p. 171.

- Rice, Michael (2002). Who's Who in Ancient Egypt?. Abingdon, UK: Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415154499.

- “Archaeologists, Feminists, and Queers: sexual politics in the construction of the past”, in Pamela L. Geller, Miranda K. Stockett, Feminist Anthropology: Past, Present, and Future. University of Pennsylvania Press. 2010. pp. 89–102. ISBN 0-8122-3940-7.

- Reeder, Greg (2000). "Same-Sex Desire, Conjugal Constructs, and the Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep". World Archaeology. 32 (2): 193–208. doi:10.1080/00438240050131180. JSTOR 827865.

- McCoy, John (Dallas Morning News) (20 July 1998). "Evidence of Gay Relationships exists as early as 2400BC". Egyptology.com. Greg Reeder. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- W. Holland (2006), "Mwah ... is this the first recorded gay kiss?" The Sunday Times, January 1, 2006. The Times.co.uk (Subscription required for access.)

- Moussa, Ahmed & Altenmüller, Hartwig (1977). Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep (in German). Darmstadt, Germany: Philipp von Zabern.

- Lorna Oakes, Pyramids Temples and Tombs of Ancient Egypt: An Illustrated Atlas of the Land of the Pharaohs, Hermes House:Anness Publishing Ltd, 2003. p.88

- Porter & Moss (1981). Malek, Jaromir (ed.). Topographical Bibliography III: Memphis, Part 2: Saqqara to Dahshur (PDF) (revised ed.). Oxford: Griffith Institute. pp. 641–644, Plan LXVI. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Hannig, Ranier (2003). Ägyptisches Wörterbuch I. Mainz, Germany: Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-3088-X.

- Barta, Miroslav (2001). Abusir V: The Cemeteries at Abusir South I. Prague: Czech Inst. of Egyptology. ISBN 80-86277-18-6. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Teeter, Emily (2011). Religion and Ritual in Ancient Egypt. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61300-2.

- Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences. "Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae". Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae. Registration (free) required for access; see notes. In German, with limited English translation. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- Baines, John (1985). "Egyptian Twins". Orientalia. 54 (4): 461–482. JSTOR 43075353.

- Allen, James (2010). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74144-6.

- Newberry, Percy (1893). Griffith, Francis L. (ed.). Beni Hasan Part II (University of Heidelberg scanned copy for ed.). London: Egypt Exploration Society. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Dunn, Jimmy. "The Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep at Saqqara in Egypt". Tour Egypt. Government of Egypt. Retrieved 9 January 2017.

- Allen, James (2015). Middle Egyptian Literature. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press. pp. 2–3, 59. ISBN 978-1-107-45607-5.

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston, museum record: gold cylinder seal, reign of Djedkare Isesi, Dyn. 5. Accession No. 68.115. "Seal of Office". Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Author. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- Fischer, Henry George (1996). Varia Nova III (PDF). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-87-099755-6. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- Taylor, John (2001). Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 42–43, 192–198. ISBN 0-226-79164-5.

- Malek, Jaromir (2000). "The Old Kingdom". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. New York: Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- Allen, James (2006). "Some aspects of the non-royal afterlife in the Old Kingdom" (PDF). The Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology: Proceedings of the Conference Held in Prague, May 31 – June 4, 2004. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology. ISBN 80-200-1465-9. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- The mastaba of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep by J. Hirst on Osirisnet.net

- Wilkinson, Richard (1994). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art (pbk. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28070-3.

- Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 19, 55. ISBN 978-0-67-403065-7.

- Janosi, Peter. "The Tombs of Officials" (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art (exhibition catalog). Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2008). "Vater, Brüder und Götter: Bemerkungen zur Szene der Übergabe der Lotosblüte" (PDF). In Spiekermann, Antje (ed.). Festschrift Bettina Schmitz (in German). Hildesheim, Germany: Hildesheim Museum, Verlag Gebrüder Gerstenberg. pp. 17, 25–26, Fig. 4. ISBN 978-3-8067-8725-2. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

Singen, während in diesem (Grab) das Opferritual durchgeführt wird, des (Lieds) vom göttlichen Bruder. Steige du auf zu ihm.

- Baines, John (2014). "Not only with the dead: banqueting in ancient Egypt" (PDF). In Ghitta, Ovidu (ed.). Historia 59. Cluj-Napoca, Romania: Universitatea Babeş-Bolyai. pp. 4, Fig. 4. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Ziegler, Christiane (1999). "Slab Stela of Nefret-Iabet (Cat. No. 51), Slab stela of Wep-em-Nefret (Cat. No. 52)". In Fuerstein, Carol (ed.). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 242–244. ISBN 0-87099-906-0. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Ćwiek, Andrzej (2003). Relief Decoration on the Royal Funerary Complexes of the Old Kingdom (PDF). Poland: University of Warsaw (doctoral dissertation). Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- Booth, Charlotte (2015). In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians. Stroud, UK: Amberley. ISBN 978-1445643-519.

Literature

- Ahmed Moussa & Hartwig Altenmüller (1977), Das Grab des Nianchchnum und Chnumhotep. Darmstadt, Germany: Philipp von Zabern. This is the generally accepted publication of the tomb. In German. ISBN 978-3-8053-0050-6

- James Allen (2005), The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts, Series: Writings from the ancient world (23), Peter Der Manuelian (Ed.), Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-182-7

- John Baines (2013). High Culture and Experience in Ancient Egypt. Bristol, CT: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-84553-300-7

- Charlotte Booth (2015), In Bed with the Ancient Egyptians, Stroud, UK: Amberley.ISBN 978-1-44-564343-4

- Thomas A. Dowson, "Archaeologists, Feminists, and Queers: sexual politics in the construction of the past". In, Pamela L. Geller, Miranda K. Stockett, Feminist Anthropology: Past, Present, and Future, pp 89–102. University of Pennsylvania Press 2006, ISBN 0-8122-3940-7

- Ian Shaw, Editor (2000), The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, New York:Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7

- William K. Simpson (2003) "Three Autobiographies of the Old Kingdom," in W.K. Simpson (Ed.), The Literature of Ancient Egypt. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, pp. 401–413. ISBN 978-0-300-09920-1

- John Taylor (2001), Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt, Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-79164-5

- Emily Teeter (2011), Religion & Ritual in Ancient Egypt, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61300-2

- Leslie Ann Warden (2013) Pottery and Economy in Old Kingdom Egypt, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00-425-985-0

- Richard Wilkinson (1994). Symbol and Magic in Egyptian Art, New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28070-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Niankhkhum and Khnumhotep. |

- Virutal exploration of their mastaba

- John Hirst and Thierry Benderitter, "The Mastaba of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep," Complete virtual tour of mastaba. Osirisnet.net

- Museum of Fine Arts Boston, "The Giza Archives." A trove on the Old Kingdom, including Giza Mastabas series and Reisner publications. Gizapyramids.org

- Greg Reeder, "The Tomb of Niankhkhum and Khnumhotep." Schematic of pillars in forecourt; detail photo of both men's names inscribed on Türrolle of second vestibule; with bibliography. Emphasis on significance of tomb for the LGBT community. Egyptology.com

- Mark Smith (2009), "Democratization of the Afterlife," UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. More about diffusion of mortuary texts in Egypt. eScholarship.org

- University College London, "Digital Egypt for Universities." Material on all phases of Egypt's religion and history. Ucl.ac.uk