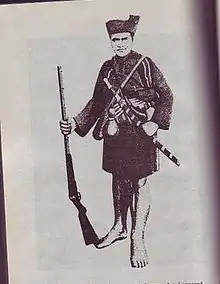

Khai Kam

Khai Kam (1864–15 September 1919) was a Chin leader who fought the British forces when they invaded Chin Hills/Chin State in the late 19th century. Two years after the British had conquered the Chin Hills, he led a rebellion to overthrow the British administration from Chin Hills. Unsuccessful in his rebellion, Khai Kam was sentenced to life imprisonment on the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. He was released in 1910 and returned to the Chin Hills.

Khai Kam | |

|---|---|

The Great Khai Kam | |

| Born | 1864 Khuasak, Tedim District |

| Died | 15 September 1919 Khuasak |

| Nationality | Zomi-Chin |

| Years active | 1888-1894 |

| Known for | Sizang-Gungal Rebellion |

Early youth

Khai Kam was the son of Sizang chief Pu Khup Pau and Pi Cing Niang. He was born in 1864 at Khuasak, Tedim Township.

British invasion of Chin Hills (1888-1889)

The Kingdom of Burma fell under the British rule in 1885 and Kale-Kabaw valley, bordering the Chin Hills became the British territory. The British had several meetings with the Chin tribal leaders to discuss the recognition of British authority, the issue of raiding made by the Chin to the plains and to open a trade route linking Burma to India. The negotiation failed as the Chin made several raid in to the plains, defying the British. The Tashon, the most powerful tribe in Chin Hill at that time, also harbored the Shwe Gyo Phyu prince and his followers who rebelled the British in central Burma. Ultimatum was sent to the Sizang chief to deliver Khai Kam together with the captives whom he carried off . Ultimatum was also sent to the Tashon council to deliver the Shwe Gyo Phyu prince and his followers. When the ultimatums were ignored, the British made preparation to invade the Chin Hills.[1]

Preparation for the expedition of 1888-1889

The British spent the month of November 1888 preparing for the expedition. Brigadier-General Faunce and Captain Raikes, established defensive positions long the valley. A levy of Military Police (later 2nd Battalion of Burma Rifle) guarded the Yaw valley against the depredations of the Southern Chins. Capt. Raikes and his assistant Mr. Hall collecting intelligence about the Chin, their village and the routes into the hills.[1] Hills coolies were collected in Assam and sent for the expeditions. The forces for expedition were gathered at Kanpale (Stockade No.1) and Gurkha 42nd Battalion was added for the expeditions.

Strategy for invading Chin Hills

The strategy was to first march against the Sizang head village, Khuasak then deal with the surrounding villages. The route selected for the advance of the column was from Kanpale to the summit of Leisan range.[1] There were no road to the hills at that time, therefore, a road had to be constructed for the main invading force and their heavy weaponry. At the beginning of December 1888, the road construction was completed until the foot of the hill, there they established No.2 Stockade i.e. Zawlkin/Khai Kam village. The road construction continued towards the hills and the reach at Phatzang where a rough No.3 stockade was established.

The Chins Offensive

The Chin learned about the invasion and made necessary preparation themselves. The Sizang council sent Khai Kam of Khuasak to meet Khawcin (the chief of Kamhau) at Tedim. The next day a force consisting of 1,200 (Sizang), 400 (Kamhau) and 30 (Sukte) prepared to defend their motherland.[2] At Khuasak, the Chin warriors were feasted by slaughtering a mithun. The Tashon also gathered warriors from her powerful neighbouring tribes.

On 7 December 1888, the Sizang started their offensive by attacking the road construction party, wounding Lt.Palmer.[1] Lt.Palmer later died on that wound. On 24 December, the Sizang again attacked the road working party and killed a sepoy of 2nd Gurkha. On Christmas Day, the combined forces of Sizang, Kamhau an Sukte attacked on the working party under the direction of Lt. Butcher of 42nd Gurkha Bn. The Sizang were in constant co-ordination with the Tashons. On 10 December 1888, the great force of Tashon made a simultaneous attack on the villages of Sihaung, Kyawywa and Kundu. At the same time, 80 Tashon warriors clashed head to head with 42nd Gurkha Light infantry led by Capt. Westmoreland. On the same date, the Sizang attacked Indin (Sawbwa’s capital) and a combined force of Sokte and Kamhau attacked the military post at Kangyi (20miles north of Kalemyo).[1] The Chins showed their planning abilities and military capabilities in this simultaneous attack to the various British positions.

The British officers were impressed by the Chin capabilities as political officers Mr.Carey and Mr.Tuck[1] wrote: "The Chins were in great force, and we now know that Tashons and Siyins (Sizang) were fighting side by side on this occasion. The Chins swooped down from the heights on to the party, which was working on a narrow spur, and attacked them from all four sides, fighting under cover of heavy undergrowth. The collies bolted and the troops fell back after holding their ground some little time. Whilst disputing every stage of our advance into their hills, the Chins showed considerable tactical ability by taking the offensive in the plains and attacking Shan villages and our posts in the rear of advancing column".

Chin Hills Expedition (1888-1889)

Since, the Chin showed their military skills by inflicting some losses on the invading forces, the British Army have now taken the Chin seriously. Field Marshal Sir George Stuart White Commander-in-Chief of Burma, personally came to supervise the expeditions. He arrived in Kanpale on 30 December 1888 and accompanied the expedition forces.[1]

On 27 January 1889, the road workers were again attacked by the Chin. The workers were sent back to the No.3 Stockade and the British troops engaged with the Chin. The Chin made them very resistance but the British troops managed to push the Chin back slowly towards the hills until they reached heavily fortified position at Leisanmual (Red Rocky Gate). The Chin stood firm at Leisanmual stockade which was a formidable and skillfully placed stockade. The stockade was also the last defensive line for the Chin. Attempts were made to overcome the stockade but, a stubborn resistance made by the Chin made it very difficult. The British political officers Mr. Carey and Mr. Tuck[1] noted the difficulty as “their routes always heavily stockade and the stockades generally held by the enemy, who never ceased to ambush when opportunity occurred, both day and night (Carey & Tuck 1896, p 28)”.

The British attacking force at Leisanmual were reinforced by the 42nd Gurkha Bn led by Lt.Col Skene. Field Marshal Sir George Stuart White himself joined the force. The attack at Leisanmual was described by Field Marshal Sir George Stuart White as "Enemy yesterday attacked our working party on road above this and held our covering party, 40 British and 100 Gurkhas, from 9-2, when I arrived and ordered their positions to be charged. We carried all, driving them entirely away, getting off ourselves wonderfully cheaply. Only one Norfolk dangerously wounded. Enemy in considerable numbers, using many rifles and plenty ammunition. They fired at least 1000 rounds, standing resolutely until actually charged, even trying to outflank at once. 'Most difficult enemy to see or hit I ever fought'". The reinforcement made a difference to the battle as the British overcome the stockade. The battle at Leisenmual was a serious blow to the Sizang, realizing that it was impossible to save their villages. On 22 January, Gen.Faunce proceeded to the summit of Leisan range after several skirmishes. There they established No.4 stockade on 31 January 1889.

During one of these operations a Lophei Chief Khup Lian personally fought hand to hand with a British soldier and captured a semi-automatic rifle. This was the first semi-automatic gun to reach the hands of the Chin people. He recorded this in a stone inscription which reads "I am the 15th generation down from the house of Thuantak who is the original progenitor of the Siyin Tribe. Being an orphan from childhood I exerted myself all alone in many enterprises by which I became a self-made man with many and various achieve-ments. When the British on 1888 undertook their first expedition against us (the Chins) I attainded the age of 20 years and I played an active part in the defence against them. When the British troops marched up the Signalling at No. 5 Stockade the united forces of the Siyins. Suktes and Kamhaus made a good resistance to the British attack which was easily repulsed. On this occasion I personally captured one rifle. When the second expedition took place in 1889 the British, too well armed to be resisted against, carried the day: hence the annexation of Chin Hills".[2] (Note: This is not a full inscription)

British occupation of Sizang Valley (1889)

Before the arrival of British force at Sizang villages, Khai Kam burned his capital Khuasak then moved into the jungle. At the same time over 2,000 warriors of the Sizang, Kamhau, Sukte and Khuano were assembling at the village of Buanman. The British fired the cannonballs at Buanman and then it exploded spectacularly, thus, the Chin realized the superiority of the British force. By February 1889, the British captured Khuasak, Buanman and Thuklai where the British military post Fort White was built. The name of the Fort was in honour of Gen. Sir George White. The British then destroyed the whole of Sizang villages as British political officers Carey and Tuck reported "By 6th March not a single Sizang village remained in existence. The destruction of Sizang villages was accomplished with a good deal of firing, but very little damage to life and limb (Carey & Tuck 1896, P29)". Although, villages were burnt to ground, Khai Kam did not surrender. Instead, he moved his headquarter to Suangpi from where he continued his resistance movement against the British. They ambushed the British, they cut telegraph cables and stole cattle from the British whenever possible. The Sizang resisted the British from the forest for two years. They were constantly moving their hideout whenever the British knew their location.

British occupation of Chin Hills (1890)

In September 1889, the British northern column attacked Suangpi, Dimpi and Dimlo. The British burned Suangpi in November but instead of surrendering, Khai Kam simply moved again his headquarter to Pimpi. On 11 December, the British attacked Montok but the people resisted the British column rather than saving their burning newly built huts. The British then temporarily abandoned their attempt to defeat the Sizang, who resisted under the leadership of Khai Kam. The British then marched to subdue the Tashon who were the most powerful tribes in the whole of Chin Hills at that time. The British believed that Sizang would surrender if Tashon submitted to the British. In March 1890,[3] the Tashon surrendered to the British, followed by the Sizang in April 1890. On the first of September 1890 Khuppau and Khai Kam of Khuasak surrendered their slaves. On that day, in a ceremony held in Thuklai, Sizang chiefs Manglun (Limkhai), Kamlam (Thuklai), Khuppau (Khuasak), Dolian (Buanman) and Khuplian (Lophei) made an oath of friendship with political officer R. S. Carey. A mithun was slaughtered for the ceremony, and its tail was dipped in the blood. Pu Kamlam took the tail of the mithun and stroked the legs of Mr. Carey, and said; "Let us forget our wars in the past; should you break our peace agreement, may you fall like the hairs of mithun and pigs, and should the Sizang break this peace agreement, may the Sizang fall like the hairs of mithun and pigs." After the ceremony, Mr. Carey announce British recognition of the existing Sizang chiefs.

Sizang-Gungal Rebellion (1892-1894)

Since the British occupied in Chin Hills, heavy fines were imposed for any sign of rebellion, collies were demanded all over Chin Hills, disarming the Chin by confiscating their guns and freeing their slaves.[2] The Chin people were not happy with the British conduct, as a result, several rebellions had taken place.

In the Gungal area (right bank of Manipur River), Kaptel village under Chief Thuam Thawng, attacked the British outpost at Botung. Because of his action, the British demanded the surrender of Thuam Thawng. Chief Thuam Thawng did not bow to the British demands, instead of surrendering, he planned with Khai Kham to drive the British out of the Chin Hills. The Sizang chiefs (except Mang Lun of Sakhiling) held a conference and agreed unanimously to start a rebellion. This plan also got approval from Tashon, Hualngo and Zahau. Khai Kam and Thuam Thawng first decided to remove the political officers, the township officers and the Interpreters, so that there should be none left to advise and guide the British troops in Chin Hills.[1]

Thuam Tawng then invited the political officer Mr.Carey to take a fresh oath of submission. Mr.Carey had travelled to Southern Chin Hills, therefore, Maung Tun Win (Township officer), Aung Gyi and Aung Zan (interpreters) were sent for the mission. Although they were warned about Thuam Thawng and Khai Kam plan by Sakhiliang Chief Mang Lon and Kamhau Chief Do Thang, they proceeded as planned. Khai Kam and Pau Dal (son of Thuam Thawng) choose 200 warriors for rebellion. When the British delegation, Maung Tun Win, Aung Gyi and Aung Zan got to the Pumva village, they were assassinated and Sizang-Gungal rebellion was initiated.[1]

The majority of the people taking part in this rebellion were Sizang, Gungal and Sukte. The Sizang had 18 villages and all of the villages except (Vokla, Naripi & Sakhiliang) rebelled. Out of 9 Sukte villages, Dimlo and Dimpi rebelled. All of Gungal villages (10 villages) except (Mwial, Laitui and Puyan) rebelled. The plan was the Gungal and Sukte to operate in Tedim areas and the Sizang to operate in Fort White areas. The Gungal and Sukte attacked the British posts and the Sizang blocked Kalay-Sizang road, cut the telegraph wires, stole the cattle’s and destroyed the vegetation.

British operation to crush the rebellion

The British quickly learned about the rebellion and sent a large force of 2,500 rifles with two mountain guns led by Brigadier General Arthur Power Palmer to crush the rebels. In 1892 November 14, the British troop and Sizang rebels clashed at Pimpi. The Sizang burned Pimpi then fled into the jungle. By the end of 1892, the British burned all of the rebelling villages as a punishment for the rebellion. The rebellion leader Khai Kam and his followers were still largely present in the Jungle. In the early part of 1893, the British then turned their focus to Thuam Thawng’s Gungal areas. The British made a surprised attacked at Kaptel, driving Chief Thuam Thawng to Heilei. Thuam Thawng resisted the British force from Heilei stockade which was destroyed by a mountain gun. Thuam Thawng then again fled to Muizawl village. The Muizawl was also captured by the British along with Thuam Thawng and his son Pau Dal. They were sent to Kindat Jail in Myingyan where both of them died in that jail.[1]

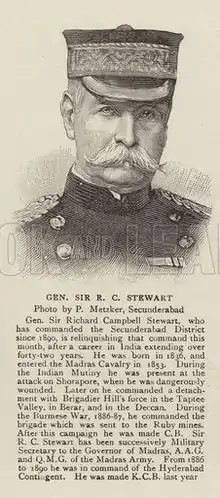

By the end of 1893, all of the Sizang chiefs surrendered except Khai Kam and his followers. He hid in the jungle and continued fighting the British. By the end of 1893, his strength was recorded at 127 fully armed and their families all belong to Sizang and Thuklai clans. Up until this point, the rebellion was commanded by a very experienced senior commander Brigadier General Arthur Power Palmer. General Sir Arthur Power Palmer received The Companion Order of the Bath CB for his excellent services for the suppressive campaign against the Siyin-Gungal Rebellion[4] However, unable to crush the rebellion swiftly, the British government then dispatched Major-General Richard Campbell Stewart, the Commander-in-Chief in Burma to personally supervise the rebellion.

On 21 Feb 1893, the military the military situation was reported by Major General R. C Stewart follows:

"I beg to note, for the Chief Commissioner‘s information, the state of affairs in the Chin Hills, as the result of my late visit to Fort White and Hakha. Note on the state of affairs in the Chin Hills in February 1893. Military Situation: The Chief Commissioner is aware of the circumstances connected with the murder of the Myook and a portion of the escorts by the Siyins (Sizang) and Nwengals (Gungal), and subsequent telegrams and diaries have related the progress of the revolt and of the operations which were deemed necessary to suppress it. On the first outbreak of the Siyins (Sizang) on the 9th October 1892 the garrisons of Fort White was reinforced by two guns of No. 7 Bombay Mountain Battery, and 100 rifles with Headquarters, 1st Burma Battalion, under Captain Presgrave, and subsequently by 200 rifles Norfolk Regiment, under Captain Baker, which enable the offensive to be taken with vigour; and General Palmer, Commanding the Myingyan District, arrived at Fort White on the 1st December and assumed control of the operations. As the most effective way of dealing with the Siyins (Sizang), General Palmer asked for more troops, and so 300 rifles, 5th Burma Battalion under Lieutenant Taylor, and the headquarters and 400 rifles, 6th Burma Battalion, under Captain Keary, D.S.O., were added to the force.

Posts were then established at Dimlo, Phunnum, and Montok; and on 2 January General Palmer with two guns, 100 rifles, Norfolk Regiment; 50 rifles, 21st Pioneers, 200 rifles, 1st Battalion; 100 rifles, 5th Burma Battalion; moved from Fort White across the Nankate [Vangteh] and on the 13th January occupied Kaptial[Kaptel], the principal and most recalcitrant village of the Nwengals. The policy throughout had been to harry the revolted tribes, and to destroy their grain supplies as much as possible. Small parties have been despatched daily from several posts to search the valley and ravines, and to hunt up Chins still lingering in the vicinity of the occupied villages. The results have been satisfactory and the tribes are being severely punished. It is difficult to estimate what their losses have been, because in all encounters with our troops the Chins have invariably been seen to carry off their wounded. On our side the losses have been extremely heavy, a total of 53 having been killed and wounded since the operations commenced. When I left Fort White General Palmer and Mr. Carey were very hopeful that both the Nwengals and the Siyins would shortly submit. Some guns had already been brought in from villages across the Nankate, and Dimlo, Pomvar and other Siyin villages were asking terms. I have every reason to hope, therefore, that full submission may shortly be expected, and I consider it a matter of congratulation that the revolt has been localised, and that the neighbouring tribes have not joined in it".[4][5]

The British found traces of rebels but, they were unable to fight them in the dense Jungle. On January and February 1894, Lieutenant Sutton searched them from Leisen range and Lieutenant Mockler search them from north to south. They found a track leading to rebel hideout and several rebels were killed, captured and prisoners were taken. The British also took casualties of 1 Gurkha killed and 1 wounded. The British destroyed all the grains that they can find to starve the rebels. On 24 February the Gurkhas surprised the rebels in camp, killing and capturing several. There, the British learned that the rebels were supplied by their relatives residing in Tavak (located in the valley) and Thuklai. The British then ordered to stop trade between the Sizang and the plains. The Generals were frustrated that started to use harsh measures. Do Thang (Sukte Chief) was arrested and asked the villagers to capture the rebels in order to purchase his liberty. By the middle of 1894, only 27 rebels were left fighting the British.[1]

Collective punishment

The British authority were frustrated about the rebellion, they started to use dirty tactics to capture Khai Kam and his followers. They stopped all Sizang cultivations, villages were fined heavily for the conduct of rebels, whilst every Chief and village elders were made to assist the British finding the rebels. These harsh measure had significant effect as more rebels finding themselves hemmed in, therefore on 23 April 1894, 23 rebels were surrendered.[1] The four left were Khai Kam, Khup Pau (his father), Mang Pum (his brother) and Pu Kam Suak. Although only four remained they did not surrender and continued to fight from the jungle.Because of those harsh measures, the people as a whole were suffering. The Sukte and Kamhau were anxious for the release of their Chief Do Thang whom the British promise to release only when villagers delivered Khai Kam and his followers. The Sakhiliang were also tired of the struggle. The Chin were worried that if the trade route remained close, they would all starve during the rains.

However, the people were determined to hold information for Khai Kam’s family. The British then so frustrated, they arrested all the remaining male relatives of Khai Kam as hostages. Learning their relatives lives were at stake, on 16 May 1984 (1894?)Khai Kam, Khup Pau (Khai Kam father), Mang Pum (Khai Kam younger brother) and Pu Vum Lian and Pu Suang Son surrendered.[4] They were immediately transported to Kindat jail in Myingyan District. When he was led from Thavak to the Kindat jail the locked chains opened by themselves three times but he did not attempt to flee.[5] The guard commander was puzzled about the miraculous happening. This was the last rebellion against the British until (Hakha-Thado-Khuangli Rebellion in 1917). After the arrest, the hostages and Chief Do Thang were released and the trade route was re-opened.

Life imprisonment

Khai Kam was sentenced for life and transported to the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. The British remarks "Never trust a Sizang, never allowed Khai Kam to return to Chinland". Khup Pau and Mang Pum got 4 years and 3 years respectively at Rangoon jail. Mang Pum later worked for the government and appealed to the British government for the release of Khai Kam.[5]

Return to Chin Hills and death

Upon successful appeal by his brother to the British authority, Khai Kam was released on 14 May 1910 and returned to Chin Hills. When Thado-Kuku, Hakha and Khuangli rebellion happened in 1917, Khai Kam was employed by The British as an advisor during Hakha-Thado Rebellion in 1917.[5] He died on 15 September 1919.

Honour

The University of Kalay, Sagaing Division, Myanmar was once officially called "Khai Kam University" in honour of Pu Khai Kam. The best sports arena in Hakha, Chin State is also called "Khai Kam Sport Centre" to honour Pu Khai Kam. The part near 9miles at Kalaymyo was also named Bo Khai Kam Park in honour of Pu Khai Kam.

References

- Tuck, Carey (1896). The Chin Hills. Burma: Government Printing.

- Son, Dr.Vum (2011). Zo History. Aizawl, India: Authour.

- Reid, A S (1893). Chin Lushai Land. Aizawl, India: Firma-KLM Private LTD.

- Dal, Thang Za (2010). The Chin/Zo People of Bangladesh, Burma and India XVII. Hamgurg, Germany: Authour.

- Hau, Dr. Vum Ko (1896). A Profile of Burma Frontier Man. Bandung, Indonesia: Authour.