Kefermarkt altarpiece

The Kefermarkt altarpiece (German: Kefermarkter Flügelaltar) is an altarpiece in Late Gothic style in the parish church in Kefermarkt, Upper Austria. It was commissioned by the knight Christoph von Zellking and is estimated as finished in 1497. The richly decorated wooden altarpiece depicts the saints Peter, Wolfgang and Christopher in its central section. The side panels depict scenes from the life of Mary, and the altarpiece also has an intricate superstructure and two side figures showing saints George and Florian. The identity of its maker is unknown, but at least two skilled sculptors appear to have created the main statuary of the altarpiece. Throughout the centuries, the altarpiece has been altered and lost its original paint and gilding. A major restoration was made in the 19th century under the leadership of writer Adalbert Stifter. The altarpiece has been described as "one of the greatest achievements in late-medieval sculpture in the German-speaking area."

History

Commission and creation

Christoph von Zellking, lord of nearby Schloss Weinberg and adviser to Emperor Frederick III, commissioned the building of a new church for Kefermarkt between 1470 and 1476.[1][2] In his last will and testament from 1490 he provided the money to pay, in installments, for an altarpiece dedicated to Saint Wolfgang also after his death. When the will was written, the altarpiece must already have been commissioned, and work on it may already have been started. In the following year, Christoph von Zellking died, and was buried in the choir of the church.[3] While the altarpiece in Kefermarkt does not carry any inscriptions or other hints as to its origins, several circumstances indicate that it remains the altarpiece commissioned by Christoph von Zellking. A receipt from 1497 (later lost) documented the final payment for the altarpiece, indicating that the altarpiece may have been installed in the church that year. A rood cross from the church in Kefermarkt also bears the date 1497, indicating that the church would have been finished by then and the furnishings installed.[1]

The altarpiece was made by a main sculptor, who is often referred to by a notname as the Master of the Kefermarkt Altarpiece.[4] It has been assumed that he was the head of a workshop, which together with its main sculptor made two of the figures in the central section (Saint Wolfgang and Saint Peter), the reliefs on the wings, and most of the smaller statuary. The architectural elements and the superstructure may have been made by a cabinet maker's workshop.[5] The identity of the main sculptor and the location of the workshop has been discussed for a long time. Because of its unusual quality, it has unconvincingly been proposed that the altarpiece was made by Tilman Riemenschneider, Veit Stoss, Michael Pacher and Albrecht Dürer.[6] Most scholars have concluded that the workshop which produced the altarpiece was active in Passau, but since few comparable works of art from Passau have been preserved, no definitive conclusions have been drawn. Similarly, it has been proposed that one Martin Kriechbaum would be the Master of the Kefermarkt Altarpiece.[4] He is mentioned in archival records as "painter", but this doesn't necessarily mean that he was not also skilled in woodcarving, and it is known that he had commissions in both Upper and Lower Austria.[5]

Changes

Following the Reformation, the Zellking family became Protestant in 1558, and the Catholic church was subsequently neglected.[7] In 1629, the church was closed altogether, and re-opened only in 1667 after being taken over by Jesuits during the Counter-Reformation.[8] The church was restored in 1670 and at this time it appears that the altarpiece was altered, with changes made to make it more in line with the prevalent Baroque taste.[7][9] The wings could originally be closed, but were now fixed to the central section. The superstructure was enlarged and enriched with other Gothic sculptures, taken from side altars. The two large statues not standing on wall consoles next to the altarpiece were placed on top of the wings.[9]

The altarpiece was originally partially gilded and painted, but today only fragments remain of the polychromy.[10] In the late 18th century, the entire altarpiece was covered with whitewash to better suit the taste and ideals of the day. Similarly whitewashed Gothic altarpieces are known also from Niederrotweil and Moosburg.[9]

Restoration

In the first half of the 19th century, the altarpiece was suffering damage from common furniture beetles. In 1852 the pastor approached the governor of Upper Austria Eduard von Bach and asked for help with restoring it. The question engaged the local government, who viewed the altarpiece as a "national monument" and its restoration as a matter of honour.[9] The work was led by the writer Adalbert Stifter, who was also an art conservator.[11] Restoration works were carried out between 1852 and 1855. Apart from Stifter, the team of restorers included sculptors Johann Rint and Josef Rint as well as several hired workers. The restoration is well-documented and it is clear that strove to preserve and restore the altarpiece to their best abilities.[9] However, the far-reaching renovation has been criticised, not least because the complete removal of the remaining medieval polychromy. Probably, Stifter assumed that the fragments of medieval paint under the Baroque whitewash had also been applied during the Baroque period.[12] During the renovation, large parts of the superstructure had to bee replaced as it had been too heavily infected by beetles. Adalbert Stifter also provided a description of the altarpiece in his novel Der Nachsommer.[1]

In 1929, a new attempt was made to get rid of furniture beetles damaging the altarpiece.[7]

Description

The Kefermarkt altarpiece has been called "one of the greatest achievements in late-medieval sculpture in the German-speaking area."[6] The altarpiece is 13.8 metres (45 ft) high from the floor to the top of the superstructure and 6.17 metres (20.2 ft) wide.[13] It is made of linden wood (with a few details made of larch added in the 19th century) and consists of four distinct parts: a predella at the base, a rectangular central section in the form of a shallow cabinet, two wings, and an intricate superstructure.[14] Not integrated into the structure itself but part of the altarpiece ensemble are also two figures depicting Saint George and Saint Florian, today placed on consoles on either side of the altarpiece.[15]

Central section

The central section is divided into three shallow niches each holding a slightly larger than life statue of the saints Peter, Wolfgang and Christopher. They are supported by richly carved corbels and crowned by baldachins. Saint Wolfgang, the patron saint of the church, occupies the middle niche and is also slightly larger than the other saints. Peter stands on Saint Wolfgang's right hand side and Saint Christopher on his left. Saint Christopher was the personal patron saint of Christoph von Zellking, hence the prominent location of the saint in the altarpiece.[14] The statue of Saint Christopher appears to have been made by one artist, while the statues of Saint Peter and Wolfgang, as well as the side panels, by another. Especially the statue of Saint Christopher has been praised for its gaunt, expressive yet sensitive face, while the other sculptures have been described as more rigid in their expressions, and the drapery of their clothing executed with less skill and finesse.[16] Unusually, Saint Christopher is not depicted as a strong giant, which was the medieval tradition, but as a young man. His head "betrays a sensitivity found only in the greatest works of Late Gothic sculpture".[16]

The sculpture of Saint Wolfgang is the largest of the three, 220 centimetres (87 in) tall. The saint is depicted in a full bishop's attire, dressed in a cope and holding a crozier. At his feet is a model church with an axe attached to its roof, one of the attributes of the saint.[17] His facial features "show him to be a man of considerable energy and drive", according to art historian Rainer Kahsnitz.[16] Saint Peter, 196 centimetres (77 in) tall, is even more richly dressed than Saint Wolfgang. His decorated brocade cope almost completely envelop the saint. His gloved hands hold the key to heaven, his attribute, and a book. Between the folds of his dress, a papal ferula is lodged against his left shoulder.[18] Saint Christopher, lastly, is depicted as a young man carrying Christ on his shoulders. The statue measures 190 centimetres (75 in).[19] He is bare-headed and barefoot. He supports himself with a rough branch as he carries Christ across a river, and the wind ruffles his clothing.[19]

At the side of the central section, two smaller statues depicting Saint Stephen and Saint Lawrence are placed facing inwards. Both are 95 centimetres (37 in) tall and depict the saints rather traditionally in liturgical dress.[20]

Wings

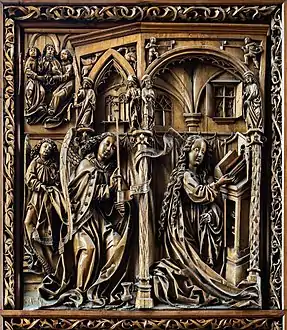

Apart from Saint Wolfgang, the main saint of the altarpiece is Mary. A statue of her is prominently placed in the middle of the superstructure, above the central panel. Furthermore, two wings each display a pair of wooden reliefs with scenes from the life of Mary. The wings could originally be closed by are now fixed. Originally, the outsides may have been painted with scenes from the life of Saint Wolfgang. The wing on the right side of the saints shows in its upper panel the Annunciation, and in its lower panel the Adoration of the Magi. The other wing shows the birth of Christ above, and the death of Mary in the lower panel.[14] The figure of Mary is portrayed in a similar way in all the panels.[21]

In the annunciation scene, Mary is portrayed kneeling in a praying stool inside a half-open structure, supported by unusually carved pillars, crowned above their capitals with figures which are probably intended to be prophets from the Old Testament. The archangel Gabriel is entering the structure, and holds a speech scroll where parts of his greeting, the Ave Maria, is visible. In the upper left corner, a depiction of God the Father among clouds and flanked by two angels, can be seen. Originally the panel also contained a dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit, but it has been lost.[21]

On the opposite side, in the top section of the wing on the saints' left side, the birth of Christ is depicted. Mary is portrayed kneeling in devotion in front of Christ, who is placed before her on a fold of her dress. On the other side, Joseph is also kneeling in front of the child. Above Mary, on the roof of the building behind them, are two angels playing a mandolin and a lute. In the background, the annunciation to the shepherds can be seen.[21]

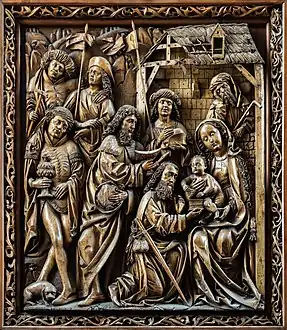

Chronologically following this scene is the panel below the annunciation scene. Here the subject of the adoration of the Magi is depicted.[21] Mary gazes on the infant Christ while one of the Magi is kneeling in front of him; the child plays with the gold in the box he is bringing. Both he and the second Magi, behind him, have taken off their hats as signs of respect.[22]

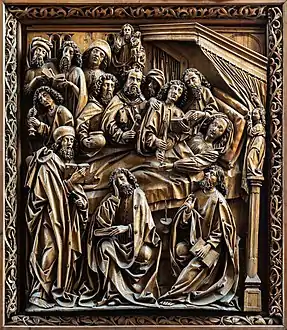

The last panel depicts the death of Mary. She is peacefully lying in her deathbed, while a diminutive angel holds the curtain apart so that the viewer can see Mary better. The twelve apostles are all present, each one depicted with individual traits. Above the head of Saint Peter, Christ appears in a cloud, receiving the soul of his mother in the form of a small figure.[15]

- The wing panels

The Annunciation, upper panel of the right wing

The Annunciation, upper panel of the right wing Birth of Christ, upper panel of the left wing

Birth of Christ, upper panel of the left wing Adoration of the Magi, lower panel of the right wing

Adoration of the Magi, lower panel of the right wing Death of Mary, lower panel of the left wing

Death of Mary, lower panel of the left wing

Superstructure

In the elaborately carved superstructure, the saints Mary, Catherine and Barbara are depicted while the upper part displays representations of Agnes of Rome flanked by busts of prophets and crowned by a sculpture of Saint Helena. The carefully made sculptures are individually designed, with great variation in clothing and attributes.[23] The superstructure itself consists of eleven pinnacles, with three main pinnacles towering over each of the saints in the central panel.[15] It has been altered on several occasions and incorporates elements from other altarpieces. Originally, it was purely architectural in its composition, with no botanical elements.[14] It is also questionable whether the figures were originally part of the superstructures, or if they were arranged in a different way.[13]

References

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 164.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 2.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 9.

- Schultes, Lothar. "Master of the Kefermarkt Altar". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 169.

- Kammel, Frank Matthias (2000). "Review of "The Kefermarkt Altar. Its Master and His Workshop" by Ulrike Krone-Balcke". The Burlington Magazine. 142 (1164): 176. JSTOR 888696.

- "Die Kirche zu Kefermarkt" [The church in Kefermarkt] (in German). Marktgemeinde Kefermarkt. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Kahsnitz 2006, pp. 164–165.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 165.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 166.

- "Flügelaltar Kefermarkt" [Kefermarkt winged altarpiece] (in German). Verbund Oberösterreichischer Museen [Union of Upper Austrian Museums]. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- Kahsnitz 2006, pp. 165–166.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 170.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 167.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 30.

- Kahsnitz 2006, p. 168.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 26.

- Oberchristl 1923, pp. 26–27.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 27.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 28.

- Oberchristl 1923, p. 29.

- Oberchristl 1923, pp. 29–30.

- Oberchristl 1923, pp. 30–31.

Works cited

- Kahsnitz, Rainer (2006). Carved Splendor: late gothic altarpieces in Southern Germany, Austria, and South Tirol. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-853-2.

- Oberchristl, Florian (1923). Der gotische Flügelaltar zu Kefermarkt [The Gothic winged altarpiece in Kefermarkt] (in German) (2 ed.). Linz: Verlag der „Christi. Kunstblätter“ Linz.

Further reading

- Adalbert Stifter: Über den geschnitzten Hochaltar in der Kirche zu Kefermarkt. Erstdruck in: Jahrbuch des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereines 13, (1853) Digitalisat, 1MB pdf

- Lothar Schultes: Der Meister des Kefermarkter Altars. Die Ergebnisse des Linzer Symposions. (Studien zur Kulturgeschichte von Oberösterreich, Folge 1), Linz 1993

- Otto Wutzel: Das Schicksal des Altars von Kefermarkt. In: Rudolf Lehr: Landes-Chronik Oberösterreich, Wien: Verlag Christian Brandstätter 2004, S. 96ff.

- Ulrike Krone-Balcke: Der Kefermarkter Altar –- sein Meister und seine Werkstatt, Deutscher Kunstverlag, München 1999 (Zugl. Univ., Diss., München 1995)