Kaimingjie germ weapon attack

The Kaimingjie germ weapon attack was a Japanese biological warfare bacterial germ strike against Kaimingjie, an area of the port of Ningbo in the Chinese province of Zhejiang in October 1940, during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[1]

These attacks were a joint Unit 731 and Unit 1644 endeavour.[1] Bubonic plague was the area of greatest interest to the doctors of the units mentioned above. Six different plague attacks were conducted in China during the war, between the start of aggression and the end of the war.

Using airdropped wheat, corn, scraps of cotton cloth and sand infested with plague infected fleas,[1] an outbreak was started that resulted in a hundred deaths, infections and mild to severe bodily mutilations.[2] The area was evacuated and a 14-foot (4.3 m) wall was built around it to enforce a quarantine. The area was eventually burnt to the ground to eradicate the disease.[2]

A later attack in 1942 on the same area by the two units led to the development of their final delivery system: airdropped ceramic bombs.[1] Some work was conducted during the war with the use of liquid forms of the pathogen agents but the results were unsatisfactory for the researchers.

The attacks were formed on the research of units 731 and 1644.[3] These units researched the effects of various chemicals and pathogens that had the potential to be used as biological weapons on soldiers and civilians.The aim of the development of these biological weapons was the use of the weapons to further expand the Japanese empire across Asia.[4]

These units were arms of the Japanese top-secret biological weapons program. The program was headed by general Shirō Ishii. General Ishii devised the plans for the kaimingjie germ weapon attack and played a major role in the Japanese biological weapons program,[5] specifically through securing the program's funding.[4]

Background

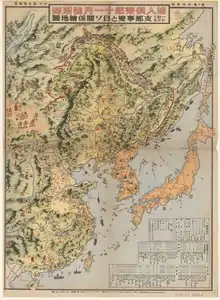

The kaimingjie germ weapon attack occurred during the Second Sino Japanese war (1937–45). This was a military conflict between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. the war broke out as a resistance to the Japanese expansion and influence on Chinese territory.

In 1931 Japan's Kwantung army occupied Manchuria in an event known as the mukden incident. Manchuria consisted of China's three north-eastern provinces. Before 1937 china and Japan fought in localised engagements but refrained from fighting a major war.[5] In Manchuria, Japan established the puppet state of Manchukuo, this became a colony of Japan.[4] Japan then continued to further expanded their occupation of China. These activities created a growing resistance against Japanese expansion.[6] The Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937 marked the beginning of full-scale hostilities between there Republic of China and the Empire of Japan.[6]

Japan's occupation of China was Declared illegal by the League of Nations; however, they were not able to pass sanctions to cease the occupation [3] as Japan had withdrawn from the league in 1933.[6] In China, the Second Sino Japanese war is known as the “war of resistance”.[7]

Research of the weapon

Japan had signed the Geneva convention, which prohibited biological and chemical warfare, however, it had not ratified the treaty and was thus not bound to the conditions of the treaty and therefore could develop a chemical and biological weapons program.[5]

Japan developed a chemical and biological weapons program, under Japan's top-secret weapons program, founded and led by General Shirō Ishii.

Ishii played a large role in pushing for the funding of the biological weapons program from the high command,[4] general Ishii was said to have been “eccentric…flamboyant and arrogant man”.[4] Ishii was accepted into the medical department of Kyoto Imperial university, there he illustrated his fast and quick mind, much advanced for his age.[4] Throughout university Japan instilled a solid sense of nationalism and patriotic duty unto their students. General Shirō Ishii has been described as an "ardent ultra-nationalist".[4]

Ishii understood science and medicine as an avenue to further Japan's nationalistic goals. Ishii joined the army where he was appointed as lieutenant. Along his journey Ishii created a network of ties with people of high standing in university and the military, these connections would later facilitate the founding of the biological weapons program, and subsequent research. His argument for the use of chemical weapons was that biological warfare would be a cheaper alternative to traditional forms of weaponry.[8]

The main units of this program were units 731 and 1644,[3] both units operated under the guise of the epidemic prevention and water purification department. This was a department of the Imperial Japanese army, and it had the public mission of preventing the spread of disease through monitoring Japan's water supply.[3]

Much of the research and experimentation took place in China and Manchukuo, although some experimentation also occurred at Imperial Navy hospitals and hospitals where wounded soldiers were being treated for their injuries. experimentation occurred at these hospitals on islands across the Pacific wherein various prisoners of war from different countries were used as subjects for the experiments, including Soviet and Chinese prisoners.[4]

Unit 731

The plan for the kaimingjie germ weapon attack was devised by General Shirō Ishii within unit 731. Unit 731 was a biological and chemical weapons development unit.[9] This unit was tasked with performing experiments into chemical agents that had the potential to be used and developed into biological weapons. The unit conducted experiments, with infectious diseases in which researchers subjugated Chinese captives and captured insurgents to cholera, syphilis, the bubonic plague. Additionally, the unit performed vivisection on their human subjects after they were infected with these various diseases.[3] invasive surgeries were performed on humans where individual organs would be removed from live subjects and studied to understand the effects of diseases.

Unit 731 also studied the effects of various toxins.[4] Specific experiments conducted included testing poison gas on prisoners, testing bubonic plague bombs, testing frostbite and its remedies on live people. Additionally this unit studied malnutrition, tetanus, anthrax, dysentery, glanders and more.[10][11]

Most of these experiments were carried out in a facility called ping fan[4] in Harbin, Manchukuo.[11] ping fan was an important site for the study of frostbite, wherein living people’ limbs were frozen and then thawed out.

Those who were conducting experiments did not employ anaesthesia and left their subjects fully awake whilst they were being operated on, as claimed by a Japanese army doctor Yasua Ken.[4]

It has also been alleged that British and American prisoners of war were subject to biological weapons experimentation at a detention camp near Mukden.[11] Although in 1986 The British ministry of defence denied any evidence of these events.

Unit 731 was involved in production and delivery of poison gasses, in 1929 a factory on Okunoshima was established to produce various poisonous gasses such as; mustard gas and phosphene gas. These gasses were then transported to the city of Kokura and packaged into artillery shells to be used on Chinese combatants and civilians, it is alleged that the gasses were used on these groups over 2000 times.[12]

Unit 731 bred yellow rats and fleas in order to spread pathogens. this took place mainly at ping fan. rats would be infected with the plague and fleas would be raised on the blood of these infected rats.[10]

Pathogen infected fleas would be encased in a weapon called the "Uji" bomb. the "Uji "bomb is a ceramic bomb, it was designed to easily explode hundreds of feet above ground, and shower infected fleas over Chinese cities.[10][13] initially the "Uji" bomb was made of a steel casing but this proved inadequate as very few pathogens survived the heat generated by the initial explosion, therefore general Ishii modified the bomb to use a ceramic casing in place of the steel frame.These new "Uji" bombs were tested in ping fan airfields on human subjects.[14] These particular bombs were used to infect large areas with various pathogens.[14]

Unit 1644

The Japanese military unit 1644 was headed by Masuda Tomosada, appointed by general Shiro Ishii. It was established in 1939 in Japanese occupied Nanking,[9] the unit operated under the guise of the epidemic prevention and water purification department.This unit's main function was the mass production of bacteria to be used for attacks, they also conducted experiments with various biological agents.[4] the unit focused mainly on carrying out experiments with cholera, typhus and bubonic plague.[9]

The unit also experimented with various poisons extracted from animals such as Taiwanese snake poisons from the cobra, hadi and amagasa snakes.[4]

This unit was relatively small when compared to other units in the Japanese biological weapons program. This unit received large amounts of funding despite its relatively small size.

Impact of the attack

The Kaimangjie germ weapon attack consisted of; corn and cloth infested with fleas, these fleas had been infected with cholera and the bubonic plague and were airdropped over the area of Ningbo on October 27, 1940. Rats would be infected with these fleas; the fleas would then move on and find human hosts.[5]

On October 29 the first three cases of the plague were diagnosed by local health officials in Kaimingjie. An estimated 26 deaths had occurred by November 2.[5] measures were taken in response to the situation. Quarantines were imposed on affected areas, homes were routinely disinfected. sheets and cloths were burnt as a precautionary measure and Vaccinations were soon introduced by officials. The areas of the city Most affected by the attack were evacuated and later burnt to prevent further outbreaks and completely eradicate the disease.[5] One victim, Jiand Chun Geng suffered flesh-eating ulcers. Others suffered untreated infections that led to death.[8]

There were also many casualties Leading up to this attack. Unit 731's experiments saw many victims, Dr Sheldon Harris estimated that from testing of prototype weapons 250000 civilian men and women died.[14]

There was a second Japanese attack on Kaimingjie that occurred in 1942, this germ weapon attack consisted of airdropping ceramic bombs over the city.[12]

The Aftermath of the attack and the war

Japan surrendered to American Allies on August 6, 1945. America planned prosecution of Japanese war criminals in both “major tribunals and minor trials” as quoted by General Douglas MacArthur.[5] Very little was known about Japan's biological weapons until 1944 when breakthroughs in decoding Japanese communications had been made by American intelligence.[14]

However, those who led unit 731 were not put on trial, and although information had surfaced on the Japanese biological weapons program, links were not made to unit 731[4] this was potentially an official coverup, attributed to the perceived military value seen by the US in the information that unit 731 held, such as the effects of biological agents on humans.[5] As America itself had researched biological and chemical weapons, specifically through the United States Army Chemical Corps.[14]

The failure to prosecute those involved in biological warfare may also have been due to lack of due diligence through the investigative process.

It has been speculated that the USA helped with the coverup of a factory in Okushima that produced mustard gas phosphene gas. During this coverup, thousands of tons of poison gasses were allegedly dumped into the ocean in 1946.[8] General Shirō Ishii provided the Americans with documents revealing secrets of the Japanese warfare program.[15] General Ishii was not prosecuted for his activities.

The Soviet Union captured some unit 731 personnel whilst they were fleeing from Manchukuo,[4] some of these captured men stood trial in the Khabarovsk war crime trials held between 25-31 of December 1949 in the Soviet Union. During these trials, 12 Japanese medical army researchers were convicted of war crimes.[16] within the trials Japanese Major General Yoshiyuki Kawashima testified that unit 731 had dropped plague contaminated fleas on Chinese cities, that caused epidemic plague outbreaks.[17] However, these trials were labelled as propaganda by the United States .[4] it has been said that the trials do not offer enough independent verification on the subject and certain crucial points[16]

Many of the leaders in Japan's secret biological warfare program would go on to have successful careers in America. Many of the activities undertaken by the Japanese army are omitted from historical textbooks and western culture.[3]

Historiography

Compared to other histories, the topic of the Japanese biological weapons program is relatively understudied.[4] This is due to the lack of documents and writings available on the topic.[4] Much of the information important to the topic was destroyed, lost and largely covered up. Much of the information held by the United States had been kept classified until recent times.

The first notable non-governmental Inquiry into the topic was conducted by journalists Peter Williams and David Wallace,[11] they brought to light the experimentation and attacks committed by Japanese unit 731, and the plans devised by general Shirō Ishii. They also spoke of alleged coverup of the Japanese war crimes. The works of these men brought exposure unto the subject specifically, to the western world.[4]

Historian Sheldon Harris[14] later furthered this work and brought even more exposure onto the subject, with in-depth rigour and evaluation of the subject. Harris collected research from people who had direct knowledge and experience with the events. Additionally. he brought to light the different units involved in the biological weapons program such as units 731, 1644, 100 and more.[4]

See also

References

- Gold, Hal (2004). Unit 731: Testimony. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 75–80. ISBN 0-8048-3565-9.

- Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2. DIANE Publishing. p. 485. ISBN 1-4289-1066-2.

- Pua, Derek; Dybbro, Dannielle; Rogers, Alister (2017). Unit 731: the forgotten Asian Auschwitz.

- Vanderbrook, Alan (2013). "Imperial Japan's Human Experiments Before And During World War Two".

- Guillemin, Jeanne. Hidden Atrocities: Japanese Germ Warfare and American Obstruction of Justice at the Tokyo Trial. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kelly, Andrew (December 2013). "The Sino-Japanese war and the Anglo-American response". Australasian Journal of American Studies. 32: 27–43 – via Jstor.

- Coble, Parks M. (June 2007). "China's "New Remembering" of the Anti-Japanese War of Resistance, 1937–1945". The China Quarterly. 190: 394–410. doi:10.1017/s0305741007001257. ISSN 0305-7410.

- Accessed 23 Mar. 2020. "coverups after the war" Check

|url=value (help). pacific atrocities education. - World Heritage Encyclopedia. Unit Ei 1644. World Heritage Encyclopedia.

- "Duties of Unit 731". Pacific Atrocities Education. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Reed, John J.; Williams, Peter; Wallace, David (February 1990). "UNIT 731: Japan's Secret Biological Warfare in World War II". The History Teacher. 23 (2): 206. doi:10.2307/494937. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 494937.

- "Imperial Japan's Chemical Warfare Development Program". Pacific Atrocities Education. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- "Japan's Secret Biological Weapons Program". Damn Interesting. Retrieved 2020-05-29.

- Harris, Sheldon (2002). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-1945, and the American Cover-Up. Routledge.

- Lockwood, Jeffrey (2012). "Insects as Weapons of War, Terror, and Torture". Annual Review of Entomology. 57: 205–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120710-100618. PMID 21910635.

- Havens, Thomas R. H. (1991-02-01). "peter williams and david wallace. Unit 731: Japan's Secret Biological Warfare in World War II. New York: Free Press. 1989. Pp. xi, 303. $22.95". The American Historical Review. 96 (1): 239–240. doi:10.1086/ahr/96.1.239. ISSN 0002-8762.

- Sant, Van (2012). "Japans Wartime Medical Atrocities: Comparative Inquiries in Science, History, and Ethics". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 68: 154–156. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrs049 – via Jstor.