Julius Caesar's planned invasion of the Parthian Empire

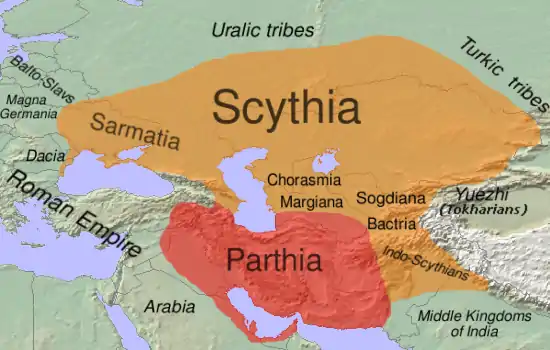

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, had planned an invasion of the Parthian Empire which was to begin in 44 BC; however, due to his assassination that same year, the invasion never took place.[1] The campaign was to start with the pacification of Dacia, followed by an invasion of Parthia.[1][2][3] Plutarch also recorded that once Parthia was subdued the army would continue to Scythia, then Germania and finally back to Rome.[4] These grander plans are found only in Plutarch's Parallel Lives, and their authenticity is questioned by most scholars.[5]

| Caesar's planned invasion of Parthia | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Roman-Parthian Wars | |

| |

| Operational scope | Dacia, Middle East and Central Asia |

| Planned | for 44 BC |

| Planned by | Roman Republic under Julius Caesar |

| Target | Burebista's Dacian kingdom, Parthian Empire, various other states and peoples |

| Executed by | Planned:

|

| Outcome | Eventual cancellation and diversion of Roman forces among civil war parties |

Preparation and invasion plans

There is evidence that Caesar had begun practical preparation for the campaign some time before late 45 BC.[6] By 44 BC Caesar had begun a mass mobilization, sixteen legions (c.60,000 men) and ten thousand cavalry were being gathered for the invasion.[7][8] These would be supported by auxiliary cavalry and light armed infantry.[9]

Six of these legions had already been sent to Macedonia to train, along with a large sum of gold for the expedition.[9] Octavius was sent to Apollonia (within modern Albania), ostensibly as a student, to remain in contact with the army.[10] As Caesar planned to be away for some time he reordered the senate[10] and also ensured that all magistrates, consuls, and tribunes would be appointed by him during his absence.[11][12] Caesar intended to leave Rome to start the campaign on 18 March; however, three days prior to his departure he was assassinated.[1]

The expedition was planned to take three years.[13] It was to begin with a punitive attack on Dacia under King Burebista, who had been threatening Macedonia's northern border.[13][14] It has been suggested by Christopher Pelling that Dacia was going to be the expedition's main target, not Parthia.[14]

After Dacia the army was then to invade Parthia from Armenia.[2][3][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] Here the ancient sources diverge. Suetonius states that Caesar wished to proceed cautiously and would not fully engage the Parthian army unless he could first determine their full strength.[3] Although he implies that Caesar's goal was an expansion of the empire, not just its stabilization.[5] Plutarch, however, describes a bolder campaign. As he writes that once Parthia had been subdued, the army would move through the Caucasus, to attack Scythia and return to Italy after conquering Germania.[4] Plutarch also states that the construction of a canal through the isthmus of Corinth, for which Anienus had been placed in charge, was to occur during the campaign.[16][lower-alpha 3]

Plutarch's reliability

Plutarch's Parallel Lives was written with the intention of finding correlations between the lives of famous Romans and Greeks;[18] for example, Caesar was paired with Alexander the Great.[19] Buszard's reading of Parallel Lives also interprets Plutarch as trying to use Caesar's future plans as a case study in the error of unbridled ambition.[19]

Some academics have theorized that Caesar's pairing with Alexander and Trajan's invasion of Parthia, near the time of Plutarch's writing, led to exaggerations in the presented invasion plan.[5] The deployment of the army to Macedonia near the Dacian frontier and the lack of military preparation in Syria have also been used to lend support for this hypothesis.[14][20] Malitz, while acknowledging that the Scythia and Germania plans appear unrealistic, believes they were credible given the geographic knowledge of the time.[13]

Motivation for invasion

The public pretense for the expedition was that less than ten years prior in 53 BC an invasion of the Parthian Empire had been attempted by the Roman consul Marcus Licinius Crassus.[10] It ended in failure and his death at the Battle of Carrhae. To many Romans this required revenge.[lower-alpha 4] Also Parthia had taken Pompey's side in the recent civil war against Caesar.[21][lower-alpha 5]

As Rome in 45 BC was still politically divided after the civil war, Marcus Cicero tried to lobby Caesar to postpone the Parthian invasion and solve his domestic problems instead. Following a similar line of thought in June of that year Caesar temporarily wavered in his intention to leave with the expedition.[22] However, Caesar finally decided to leave Rome and join the army in Macedonia. A number of motivations have been proposed to explain his decision to continue his military career.[23] After a victorious campaign he would have, as Plutarch wrote, "completed this circuit of his empire, which would then be bounded on all sides by the ocean"[24] and return home with his lifelong dictatorship secured.[6] It has also been proposed that Caesar knew of the threats against him and felt that leaving Rome and being in the company of a loyal army would be safer, personally and politically.[22] Caesar may have also wished to heal the rift from the civil war, or distract from it, by reminding the populace of Rome of the threat of a neighboring empire.[9]

Consequence

In order to support a royal title for Caesar a rumor was spread in the lead up to the planned invasion. It alleged that it had been prophesied that only a Roman king could defeat Parthia.[7][10] As Caesar's greatest internal opposition came from those that believed he wanted royal power, this strengthened the conspiracy against him.[25] It has also been proposed that Caesar's opposition would be fearful of him returning victorious from his campaign and more popular than ever.[6][26] The assassination occurred on 15 March 44 BC on the day the senate was to debate granting Caesar the title of king for the war with Parthia.[10] However, some of the aspects of Caesar's planned kingship may have been invented after the assassination in order to justify the act.[5] The relationship between the planned Parthian war and his death, if any, is unknown.[5][27]

After Caesar's death Mark Antony successfully vied for control of the legions from the planned invasion, still stationed in Macedonia and he temporarily took control of that province in order to do so.[12] From 40 to 33 BC Rome and Antony in particular would wage an unsuccessful war with Parthia.[28] He used Caesar's proposed invasion plan, of attacking through Armenia, where it was felt the support of the local king could be relied on.[9] In Dacia, Burebista was to die the same year as Caesar, leading to the dissolution of his kingdom.[10]

Footnotes

- Caesar's invasion plan used more cavalry than Crassus's and also approached through the friendly territory of Armenia. It is believed that both these factors would have improved his chances of success relative to the earlier attempt.[9]

- From 46 BC Quintus Caecilius Bassus had control of Syria. Bassus had supported Pompey in the civil war, had murdered caeser's cousin, Sextus Caeser and defeated the new governor Caeser had sent.[15]

- Nicolaus of Damascus also mentions an intention to continue to India after Parthia.[17]

- According to Dio, the Roman people's desire for this revenge led to Caesar being given sole command of the Parthian campaign by a unanimous vote.[11]

- Parthia was aware of the political divide in Rome and that Caesar's victory in the civil war may lead to invasion.[21]

References

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg I

- Plutarch, Caesar 58.6

- Suetonius, The Life of Julius Caesar 44

- Plutarch, Caesar 58.6,7

- Townend 1983 p. 601-606

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg V

- Appian, The Civil Wars 2.110

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg VI

- Poirot, John J. (2014). The Romano-Parthian Cold War: Julio-ClaudianForeign Policy in the First Century CE and Tacitus'Annales. Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons. pp. 56–58.

- Heitland 2013 p.469–471.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.51

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Adegi Graphics LLC. pp. 137–139. ISBN 9780543927491.

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg VII

- Pelling, Christopher (2011). Plutarch Caesar: Translated with an Introduction and Commentary. OUP Oxford. pp. 438–439. ISBN 9780198149040.

- Strauss, Barry (2016-03-22). The Death of Caesar: The Story of History's Most Famous Assassination. Simon and Schuster. pp. 55, 56, 68. ISBN 9781451668810.

- Plutarch, Caesar 58.8

- Nicolaus of Damascus, Life of Augustus 26

- Stadter, Philip A. "Plutarch's Comparison of Pericles and Fabius Maximus". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 16 (1): 77–85.

- Buszard, Bradley (2008). "Caesar's Ambition: A Combined Reading of Plutarch's Alexander-Caesar and Pyrrhus-Marius". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 138 (1): 185–215. doi:10.1353/apa.0.0004. ISSN 2575-7199. S2CID 162316551.

- McDermott, W. C. (1982). "Caesar's Projected Dacian-Parthian Expedition". Ancient Society (13): 223–232. ISSN 0066-1619.

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg II

- Griffin, Miriam (2009). A Companion to Julius Caesar. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 69–70. ISBN 9781444308457.

- Campbell, Brian (2002). "War and diplomacy: Rome and Parthia, 31 BC–AD 235". War and Society in the Roman World. Chapter 9. doi:10.4324/9780203075548. ISBN 9780203075548.

- Plutarch, Caesar 58.7

- Plutarch, Caesar 60

- Strauss, Barry (2016-03-22). The Death of Caesar: The Story of History's Most Famous Assassination. Simon and Schuster. pp. 56, 68. ISBN 9781451668810.

- Malitz, Caesars Partherkrieg IV

- Bunson, Matthew (2014-05-14). Encyclopedia of the Roman Empire. Infobase Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 9781438110271.

Sources

Ancient

Modern

- Heitland, W. E. (2013). A Short History of the Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 469–471. ISBN 9781107621039.

- Malitz, Jürgen (1984). "Caesars Partherkrieg (English title: Caesar's Parthian War)" (PDF). Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. Bd. 33, H. 1: 21–59.

- Townend, G. B. (1983). "A Clue to Caesar's unfulfilled Intentions". Latomus. 42 (3): 601–606. JSTOR 41532893.

External links

- History of Rome podcast: by Mike Duncan contextualizing and describing invasion plans.