John du Pont

John Eleuthère du Pont (November 22, 1938 – December 9, 2010) was a convicted murderer and former philanthropist. An heir to the Du Pont family fortune,[1] he was a published ornithologist, philatelist, conchologist, and sports enthusiast. He died in prison while serving a sentence of 30 years for the murder of Dave Schultz.

John Eleuthère du Pont | |

|---|---|

Du Pont in February 1992 | |

| Born | November 22, 1938 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | December 9, 2010 (aged 72) State Correctional Institution – Laurel Highlands, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | |

| Spouse(s) | Gale Wenk (m. 1983; annulled after 90 days; div. 1987) |

| Parent(s) | William du Pont Jr. Jean Liseter Austin |

In 1972, du Pont founded and directed the Delaware Museum of Natural History and contributed to Villanova University and other institutions.[1] In the 1980s, he established a wrestling facility at his Foxcatcher Farm after becoming interested in the sport and the pentathlon events. He became a prominent supporter of amateur sports in the United States and a sponsor of USA Wrestling.

In the 1990s, friends, and acquaintances were concerned about his erratic and paranoid behavior, but his wealth shielded him.[2] On February 25, 1997, he was convicted of murder in the third degree for the January 26, 1996, shooting death of Dave Schultz, an Olympic champion freestyle wrestler living and working on du Pont's estate. He was ruled to have been mentally ill but not insane and was sentenced to prison for 13 to 30 years. He died in prison at age 72 on December 9, 2010. To date, he is the only member of the Forbes 400 richest Americans to be convicted of murder.

Early life

John du Pont was born on November 22, 1938, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the youngest of four children of William du Pont, Jr. and Jean Liseter Austin (1897–1988). He grew up at Liseter Hall, a mansion built in 1922 in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, by his maternal grandfather on more than 80 hectares (200 acres) of land given to his parents at their wedding by his maternal grandfather.[3] Both his parents' families had emigrated from Europe to the United States at the beginning of the 19th century and became highly successful.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the couple acquired more land and developed Liseter Hall Farm for Thoroughbred breeding, showing, and racing. His mother retained Liseter Hall Farm after the couple divorced in 1941. She added a dairy herd of Guernseys and bred Welsh ponies at the farm. John was 2 when his parents divorced. He had two older sisters, Jean and Evelyn, an older brother Henry E. I. du Pont, and a younger half brother, William du Pont III, born of their father's second marriage.

Du Pont graduated from Haverford School in 1957. He attended the University of Pennsylvania where he belonged to the Zeta Psi fraternity, and withdrew before completing his freshman year.[4] Du Pont later attended college in Miami, Florida, where he studied under and was mentored by scientist Oscar T. Owre.[5] He graduated from the University of Miami in 1965 with a Bachelor of Science degree in zoology. Du Pont went on to complete a doctorate in natural science from Villanova University in 1973.[6]

During an October 2015 podcast, Mark Schultz revealed that when John was about thirty years old, a horse he was riding threw him onto a fence, resulting in injury to his testicles. They became infected and had to be removed, resulting in androgynous characteristics for the remainder of his life.[7]

Science career

During his graduate work, du Pont participated in several scientific expeditions to study and identify species of birds in the Philippines and South Pacific. As an ornithologist, du Pont is credited with the discovery of two dozen species of birds.[8] He founded the Delaware Museum of Natural History in 1957.[9] As a young man, he served on the board, helping guide the institution toward opening in 1972. After having been part of scientific expeditions, he served as director of the museum for many years.[10]

Personal life

At the age of 45, on September 3, 1983, du Pont married 29-year-old Gale Wenk, an occupational therapist. They met after he injured his hand in an auto accident.[11] They lived together for less than six months.[12] Du Pont filed for divorce when they had been married for ten months. Wenk sued du Pont for $5 million, claiming he had pointed a gun at her and tried to push her into a fireplace.[11] The divorce became final in 1987.[12] Du Pont's will excluded her from inheriting any of his estate.[13] In 1987, it was estimated that John du Pont was worth $200 million.[14]

Interests

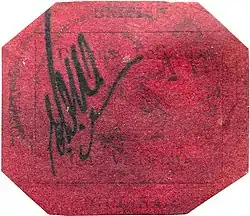

Philately

Du Pont was also a philatelist. Bidding anonymously in a 1980 auction, he paid $935,000 for one of the rarest stamps in the world, the British Guiana 1856 1c black on magenta.[15] After his death, this stamp was sold at auction for $9.5 million (inclusive of buyer's premium) at Sotheby's June 17, 2014. For the fourth time, the stamp broke the record for a single stamp's sale.[16] The unique stamp was part of the estate of du Pont. According to du Pont's will—unsuccessfully challenged by several parties—80 percent of the sale proceeds go to the family of Bulgarian wrestler Valentin Jordanov Dimitrov and 20 percent goes to the Eurasian Pacific Wildlife Foundation, based in Paoli, Pennsylvania, a group du Pont founded to support Pacific wildlife.[16] In 1986, competing as "John Foxbridge", he won the Grand Prix d'Honneur in the FIP Championship Class at the STOCKHOLMIA 86 international stamp exhibition for his display of "British North America".[17] While du Pont continued to buy stamps while in prison, he was not allowed to bring them there.[18]

Athletics

Du Pont developed the 440-acre (1.8 km2) Liseter Hall Farm in Newtown Square as a high-quality wrestling facility for amateur wrestlers.[19] He called the private group "Team Foxcatcher," after his father's noted racing stable. Du Pont established an Olympic swimming and wrestling training center and sponsored competitive events at the estate. He also allowed some people, such as Olympic champion wrestlers Mark Schultz and later his older brother Dave Schultz and his wife, to live in houses on the grounds for years. Dave Schultz also coached the Foxcatcher team.

Du Pont became a sponsor in wrestling, swimming, track, and the modern pentathlon. He was also involved in promoting a subset of the modern pentathlon (run, swim, shoot) as a separate event.[20][21] He took up athletics and became a competitive wrestler in his 50s. His only prior wrestling experience was as a freshman in high school. He began competing again at the age of 55 in the 1992 Veteran's World Championships in Cali, Colombia; following that in 1993 in Toronto, Ontario; [22] and in 1995 in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Lawsuit

In August 1988, a problem-plagued wrestling program he funded at Villanova was shut down after just two years. In December 1988, a lawsuit (which was settled out of court) claimed du Pont had made improper sexual advances to Villanova assistant coach Andre Metzger.[23]

Murder of Dave Schultz

On January 26, 1996, du Pont shot and killed Dave Schultz in the driveway of Schultz's home on du Pont's 800-acre (3.2 km2) estate. Schultz's wife Nancy and du Pont's head of security Patrick Goodale were present and witnessed the crime. The security chief was sitting in the passenger seat of du Pont's car when du Pont fired three bullets into Schultz. Police did not establish a motive. Schultz had worked with du Pont to coach the wrestling team for years.[2]

Du Pont's friends said the shooting was uncharacteristic. Joy Hansen Leutner, a triathlete from Hermosa Beach, California, lived for two years on the estate.[24] Leutner said du Pont helped her through a stressful period in the mid-1980s. She later said, "With my family and friends, John gave me a new lease on life. He gave more than money; he gave himself emotionally." She expressed incredulity about the killing. She is quoted as saying: "There's no way John in his right mind would have killed Dave."[2] Newtown Township supervisor John S. Custer Jr. said, "At the time of the murder, John didn't know what he was doing."[25]

Many people had noticed du Pont's increasingly disruptive behavior in the months before the murder.[24] Charles King Sr. blames du Pont's "security consultant", Patrick Goodale, for influencing what happened. King said, "I don't think John could shoot someone unless he was pushed to, or was on drugs. After that guy started hanging around him, my son always said Johnny changed. He was scared of everything. He was always a little off. But I never had problems with him, and my son never had problems."[25] After the shooting, du Pont locked himself in his mansion for two days while he negotiated with police on the telephone. Police turned off his power and were able to capture him when he went outside to fix his heater. In September 1996, du Pont was ruled incompetent to stand trial, as experts testified that he was psychotic and could not participate in his own defense. He was committed to a mental hospital and his condition was to be reviewed by the court in three months.[26]

During the trial, one of the defense's expert psychiatric witnesses described du Pont as a paranoid schizophrenic who believed Schultz was part of an international conspiracy to kill him.[27] He said du Pont believed people would break into his house and kill him, and that he had installed a variety of security features in his house.[27]

Du Pont pleaded "not guilty by reason of insanity." The insanity defense was thrown out by the court, and on February 25, 1997, a jury found him guilty of third-degree murder but mentally ill.[28] In Pennsylvania, third-degree murder is a lesser charge than first-degree (intentional) or second-degree (a killing occurring during the perpetration of a felony), and indicates a lack of intent to kill. In Pennsylvania criminal code, "insanity" applies to someone whose "disease or defect" leaves him unable either to understand that his conduct is wrong or to conform it to the law (The M'Naghten Rule).[29]

The jury verdict of "guilty but mentally ill" meant the sentencing would be referred to the judge, Patricia Jenkins. She could have sentenced du Pont to 5 to 40 years. Du Pont was sentenced to 13 to 30 years' incarceration and was housed at the State Correctional Institution – Mercer, a minimum-security institution in the Pennsylvania prison system.[30] Du Pont was initially confined to Cresson Correctional Institute.[3] Following the guilty verdict, Nancy Schultz, Dave's widow, filed a wrongful death lawsuit against du Pont. The amount of the settlement was not disclosed. The Philadelphia Inquirer, citing anonymous sources, reported du Pont was to pay Schultz at least $35 million.[31]

Du Pont's attorneys filed appeals. In 2000, his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court which upheld the verdict. Du Pont was first eligible for parole on January 29, 2009; it was denied. In 2010, the 3rd Circuit U.S. appeals court in Philadelphia rejected all but one issue raised on appeal (involving his use of prescribed scopolamine before he killed Schultz), and requested written briefs.[32] Du Pont's maximum sentence would have ended on January 29, 2026, when he would have been 87.[33]

Death

Du Pont died at the age of 72 on December 9, 2010, from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A spokesperson for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections said du Pont was found unresponsive in his bed at the State Correctional Institution – Laurel Highlands. He was pronounced dead at 6:55 a.m. at UPMC Somerset.[1][34] He was buried in his red Foxcatcher wrestling singlet, in accordance with his will, at the Du Pont de Nemours Cemetery in Wilmington, Delaware.[35]

Philanthropy and institutions

Du Pont founded the Delaware Museum of Natural History in 1957, which opened to the public in 1972 on a site near Winterthur donated by his relative Henry Francis du Pont. John du Pont served on the board for many years. He also helped fund a new basketball arena at Villanova University, which opened in 1986. Originally it was called the John Eleuthère du Pont Pavilion, but after his conviction, his name was removed from the facility and simply called The Pavilion. Today the facility is named The Finneran Pavilion.

Foxcatcher Farm

After his mother's death in 1988, du Pont assumed stewardship of Liseter Farm and renamed it "Foxcatcher Farm" after his father's famed Thoroughbred racing stable.[36] John never lived in the manor house; he occupied a smaller house on the estate. Days after his mother's death, he moved into the main house.[37] He maintained much of her work, but added a wrestling facility and supporting buildings for that interest.

After his arrest, du Pont sold off the dairy herd, nearly 70 Guernseys, in the fall of 1996. He ordered all the buildings at Foxcatcher Farm to be painted a matte black. The Delaware Museum of Natural History, which du Pont formerly headed and which held the dairy farm in trust, sold that portion in January 1998 after his conviction and sentencing to prison. A 123-acre (0.50 km2) segment is now occupied by the campus of the Episcopal Academy, a private independent K–12 school founded in 1785, which moved there in 2008 from split campuses located in the nearby Philadelphia Main Line communities of Merion and Devon.[38] The 90-year-old du Pont mansion, Liseter Hall, in which du Pont was raised and had lived for 57 years, was demolished by Glenn Miller Demolition in January 2013.[39] The mansion stood on a 400-acre (1.6 km2) portion of the property that is now being developed by Toll Brothers into a "master planned community of 449 luxury homes" called "Liseter Estate."[40] Most of the outbuildings were torn down, though an existing 7,000-square-foot historical barn will be used as a clubhouse in the new development.

Disputed will

Du Pont had been worth an estimated US$200 million in 1986, about $470 million in current dollars.[41] His will bequeathed 80 percent of his estate to Bulgarian wrestler Valentin Yordanov, an Olympic champion who had trained at Foxcatcher,[42] and Yordanov's relatives. In June 2011, du Pont's niece Beverly A. du Pont Gauggel and nephew William H. du Pont filed a petition to challenge the will in Media, Pennsylvania, asserting that du Pont was not "of sound mind" when he made his will. The petition claims that during that period, John du Pont asserted alternately that he was Jesus Christ, the Dalai Lama, and a Russian tsar.[43]

That petition was dismissed, and while appealed, the Superior Court of Pennsylvania has upheld a Delaware County Orphans Court order dismissing a challenge on the will on November 19, 2012.[44] Former Delaware County Court of Common Pleas President Judge Joseph Cronin dismissed the challenge for lack of standing, finding that because the niece and nephew were not named in two successive wills going back to 2006, they would not be harmed if the September 2010 will were deemed valid. A three-judge panel of the Superior Court affirmed that ruling on November 19, 2012.[44]

Representation in media

- Du Pont's murder of Dave Schultz is recounted in the 2013 true crime book Wrestling with Madness.[45]

- The 2014 film Foxcatcher, directed by Bennett Miller, was based on the events related to the Schultz brothers and exploring John du Pont's relationship with them. For his portrayal of du Pont, Steve Carell was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.[46]

- Olympic Wrestling Champion Mark Schultz, the younger brother of Dave Schultz, wrote Foxcatcher: The True Story of My Brother's Murder, John du Pont's Madness, and the Quest for Olympic Gold.[47][48]

- ESPN Films featured the story of du Pont and Team Foxcatcher in the 2015 30 for 30 series film The Prince of Pennsylvania. The film featured several former members of the Foxcatcher wrestling team, including Mark Schultz, as well as John du Pont's ex-wife Gale Denny and Mark and Dave Schultz's parents. The film, which was directed by Jesse Vile, premiered on October 20, 2015, and got its title from a letter Dave Schultz wrote to Prince Albert of Monaco rejecting his proposal for Schultz to become the coach of a wrestling team in Monaco.

- Netflix produced the 2016 film documentary entitled Team Foxcatcher which tells the story of John du Pont's involvement with wrestling and Foxcatcher Farm using interviews with many of those present as well as archival footage.

Bibliography

Books

Papers

- Amadon, Dean; Dupont, John E (1970). "Notes on Philippine birds". Nemouria. 1: 1–14.

- Dupont, John E (1971). "Notes on Philippine Birds (No. 1)". Nemouria. 3: 1–6.

- Dupont, John E (1972). "Notes on Philippine Birds (No. 2). Birds of Ticao". Nemouria. 6: 1–13.

- Dupont, John E (1972). "Notes on Philippine Birds (No. 3). Birds of Marinduque". Nemouria. 7: 1–14.

- Dupont, John E (1976). "Notes on Philippine Birds (No. 4). Additions and Corrections To Philippine Birds". Nemouria. 17: 1–13.

- Dupont, John E (1980). "Notes on Philippine birds (No. 5). Birds of Burias". Nemouria. 24: 1–6.

- Dupont, John E; Rabor, D S (1973). "South Sulu Archipelago Birds. An Expedition Report". Nemouria. Delaware Museum of Natural History. 9: 1–63. ISSN 0085-3887.

- Dupont, John E; Rabor, D S (1973). "Birds of Dinagat and Siargao, Philippines". Nemouria. Delaware Museum of Natural History. 10: 1–111. ISSN 0085-3887.

- Dupont, John E; Niles, David M (1980). "Redescription of Halcyon bougainvillei excelsa Mayr, 1941". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 100: 232–233.

References

- Jeré Longman (December 9, 2010). "John E. du Pont, Heir Who Killed an Olympian, Dies at 72". New York Times. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

John E. du Pont, an heir to the du Pont chemical fortune whose benevolent support of Olympic athletes deteriorated into delusion and ended in the shooting death of a champion wrestler, died Thursday in a western Pennsylvania prison. He was 72. Mr. du Pont was found unresponsive in his cell at Laurel Highlands State Prison near Somerset, Pa., a prison spokeswoman told The Associated Press. ...

- Longman, Jere; Belluck, Pam; Nordheimer, Jon (February 4, 1996). "For du Pont Heir, Question Was Control". The New York Times.

- "Last hurrah for historic Liseter Hall Farm". Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred. September 2005. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- Bowden, Mark; Bensen, Clea (February 4, 1996). "The Prince Of Newtown Square John Du Pont Had Millions But Lacked The Thing He Really Wanted: Expertise. So He Spent Money To Make It Look As If He Had It". Philadelphia Media Network (Digital) LLC. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- James A. Kushlan (1991). "In Memoriam: Oscar T. Owre, 1917-1990" (PDF). The Auk. 108 (3): 705–708. doi:10.2307/4088110. JSTOR 4088110.

- "DuPont heir dies in prison". UPI. December 9, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2015.

- Andrew Gurevich (October 25, 2015). "Episode 7 - Mark Schultz". On the Block Radio.com− (Podcast). Event occurs at 1:04:45. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- Newsweek staff. "AN ECCENTRIC HEIR'S WRESTLE WITH DEATH". Newsweek. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- Munroe, John (2006). History of Delaware. ISBN 9780874139471.

- Chilton, Glen (September 8, 2009). The Curse of the Labrador Duck: My Obsessive Quest to the Edge of Extinction. ISBN 9781439124994.

- Hewitt, Bill (February 12, 1996). "A Man Possessed". People Magazine. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- Pirro, J.F. "The Foxcatcher Murder". MainLine Today. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- "Last Will and Testament of John Eleuthere du Pont" (PDF). Delaware Online. September 16, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 13, 2014. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- "'Foxcatcher' fodder: John du Pont's bizarre downfall". Courierpostonline.com. January 11, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Rachlin, Harvey (1996). Lucy's Bones, Sacred Stones, and Einstein's Brain: The Remarkable Stories Behind the Great Artifacts of History, From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-6406-0.

- "Stamp owned by Delaware murderer John du Pont sells for $9.5 million". Delawareonline.com. June 18, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- "The Three Previous Stockholmia World Philatelic Exhibitions" by Bengt Bengtsson, Bulletin 1, STOCKHOLMIA2019, Sweden, 2017, pp. 30-33.

- "John du Pont and collecting stamps in jail" Archived May 29, 2015, at the Wayback Machine The Stamp Blog, March 15, 2015

- "The Value of Open Space, Save Open Space, Everything Old is New Again". Save Open Space. April 1999. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011.

- Alice Higgins (August 28, 1967). "Trials Of A Busy Pentathlete: Young John du Pont, host to the national championships, found that organizing the event could be a handicap for a dedicated competitor". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014.

- Chapter XI: "20th-Century Personages and the Arts" Archived July 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Historic Newtown Square, Newtown Square Historical Preservation Society

- "SILVERBACKS: 1994 Masters 3rd Freestyle Wrestling World Championships". silverbackswrestling.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- John Greenwald (February 5, 1996). "Blood on the Mat: The killing of an Olympic gold medalists suggest that John du Pont, patron of wrestling, was no angel". Time Magazine. Mubarak Dahir, Sharon E. Epperson.

- Randy Harvey (January 31, 1996). "Signposts to a Tragedy – Du Pont Heir". Los Angeles Times. p. 2.

- J.F. Pirro (January 12, 2007). "In Memory of a Murder". MainLine Today. Today Media.

- "Du Pont Is Ruled Incompetent for Trial in Killing of Wrestler". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. September 25, 1996. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Vigoda, Ralph; Ordine, Bill. "Defense Doctors: Du Pont Feared He Was Target Of Conspiracy He Worried About The Russians, One Said. Then He Decided The Threat Was At Home". philly.com. Interstate General Media. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- CNN (February 25, 1997). "Du Pont guilty but mentally ill in Olympic wrestler's murder". Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Law and Legal Research, Lawyers, Legal Websites, Legal News and Legal Resources Archived April 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Onecle, Crimes And Offenses – 18 Pa. Cons. Stat. Pennsylvania Statutes

- "Heir Sentenced Up to 30 Years For Killing of Olympic Wrestler". The New York Times. May 14, 1997.

- "Du Pont, Wrestler's Widow Settle Suit". Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Circuit Won't Hear Arguments on Du Pont Millionaire's Last Round of Appeals", Law

- What Ever Happened to: Imprisoned Chemical Heir John du Pont?. Newsweek (August 7, 2008). Retrieved on March 16, 2013.

- "Du Pont heir dies in prison". United Press International. December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

Du Pont fortune heir John E. du Pont, convicted of the 1996 murder of Olympic wrestler David Schulz, died of natural causes, Pennsylvania prison officials said. He was 72. Corrections spokeswoman Sue Bensinger said du Pont was found unresponsive in his Laurel Highland State Correctional Facility cell in Somerset County Thursday, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported. Bensinger said he had been ill for some time.

- Mari A. Schaefer (February 16, 2011). "John du Pont was buried in his wrestling singlet". philly.com. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Michael Yockel (September 2005). "Last hurrah for historic Liseter Hall Farm". Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved October 23, 2005.

- "When Life In The Du Pont Mansion Began To Crumble At Foxcatcher, The Obsessions Of The Son Quickly Overrode His Dead Mother's Blueblood Elegance". Articles.philly.com. December 10, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- Gammage, Jeff "Episcopal Academy prepped for big change Expansion trumps angst over move from Merion", Philadelphia Inquirer, October 21, 2007

- Bannan, Pete "Historic DuPont mansion goes under the wrecker's ball" Main Line Media News, January 25, 2013.

- "Liseter Estate at Route 252 and Goshen Road in Newtown Square to be Developed by Toll Brothers" PRWeb, November 20, 2012

- "Death In Prison For Ex-Forbes 400 Member". Forbes. December 10, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- Знаменити борци, възпитаници на НСА [Famous Wrestlers from the National Sports Academy] (in Bulgarian). National Sports Academy "Vasil Levski". Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- Alex Rose (June 15, 2011). "Du Pont Relatives Contest Validity of Late Killer's Will". Delaware County Daily Times. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2011.

- "Superior Court: Du Pont relatives have no standing to contest will". Main Line Media News. December 6, 2012.

- "Wrestling With Madness: John E. Du Pont and the Foxcatcher Farm Murder". Absolute Crime. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- "Full List of the Oscar Nominations 2015". Award Show Talk. 2015.

- Mark Schultz; David Thomas (November 18, 2014). Foxcatcher: The True Story of My Brother's Murder, John du Pont's Madness, and the Quest for Olympic Gold. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780698188709.

- Strauss, Chris (November 14, 2014). "Where are the missing seven years in 'Foxcatcher'?". USA Today. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John du Pont |

- "Flickr", Collector, May 2008.

- "How About At Your Place?" Said the Colonel", LIFE, Aug 4, 1967

- "John E du Pont video Foxcatcher Farm - 1988" Documentary including footage of du Pont at his estate and at the Foxcatcher training facility.

- Hendrickson, John (December 2014). "Turns Out That Sad Propaganda Video from Foxcatcher Was Real". esquire.com. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "LIFE photos", LIFE, US Olympic pentathlete, August 1967.

- News coverage January 26–29, 1996 on ABC, CBS & CNN; 16 minutes. About the murder and the immediate aftermath.