John Lok

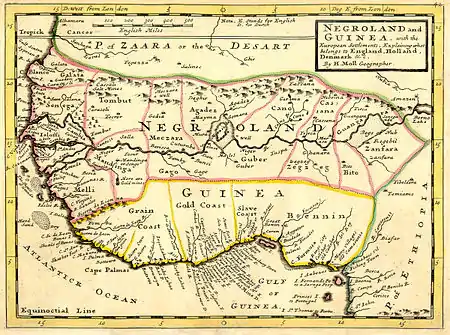

John Lok was the son of Sir William Lok, the great-great-great-grandfather of the philosopher John Locke (1632–1704). In 1554 he was captain of a trading voyage to Guinea. An account of his voyage was published in 1572 by Richard Eden.

John Lok | |

|---|---|

| Died | France |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Spert |

| Father | Sir William Lok |

| Mother | Katherine Cooke |

Family

John Lok's date of birth is unknown. He was one of the nineteen children of the London mercer Sir William Lok by his second wife, Katherine Cooke (d. 14 Oct 1537),[1] daughter of Sir Thomas Cooke of Wiltshire.[2][3][4][5]

He was a half-brother of the mercer Thomas Lok (8 February 1514 – 9 November 1556), Sir William Lok's eldest surviving son and heir by his first wife.[2] His brothers and sisters of the whole blood were:[2]

- Dorothy Lok, who married firstly the London merchant Otwell Hill (d.1543), and secondly John Cosworth of London and Cornwall, merchant. Otwell Hill was the brother of Richard Hill.[6][2][7][8]

- Katherine Lok, who married firstly Thomas Stacey of London, Warden of the Mercers' Company in 1555 together with his brother-in-law, Thomas Lok,[9] and secondly William Matthew of Bradden, Northamptonshire.[2]

- Rose Lok (26 December 1526), who married firstly the London mercer Anthony Hickman, son of Walter Hickman of Woodford, Essex, and secondly Simon Throckmorton, esquire, of Brampton, Huntingdonshire, and was a Marian exile. She died 21 November 1613, aged 86.[4][10][2]

- Alice Lok, (d.1537), died without issue.[2]

- Thomasine Lok (d.1530), died without issue.[2]

- Henry Lok (d.1571) of London, mercer, who married Anne Vaughan, by whom he was father of the poet, Henry Lok.[11][4][12][2]

- Michael Lok of London, mercer, who married firstly Jane Wilkinson, daughter of William Wilkinson, mercer and Sheriff of London, and secondly Margery Perient, widow of Caesar Adelmare, father of Sir Julius Caesar.[13][4][2]

- Elizabeth Lok (3 August 1535 – c.1581), who married firstly Richard Hill (d.1568), mercer and alderman of London, and by him had thirteen children, and secondly Nicholas Bullingham, Bishop of Worcester, who died in 1576, by whom she had one child.[6][4][14][15][2]

- John Lok, whose mother died at his birth, and he the day after.[2]

Career

In 1553 Lok travelled to Jerusalem.[2][16]

In 1554 Lok was captain of three ships, the Trinity of 140 tons, the Bartholomew of 90 tons, and the John Evangelist of 140 tons which set sail on a trading voyage to Guinea on 11 October. Although unfavourable winds kept them from leaving England's shores until 1 November, they were near Madeira by 17 November, and becalmed two days later at the Canary Islands under the Peak of Tenerife. They touched the coast of Africa at Cape Barbas, and after reaching the mouth of the Sestos River, traded down the coast, 'touching every place of consequence without any memorable incident occurring' until 13 February, when they turned back toward England. Although the voyage out had taken seven weeks, the return voyage took twenty. In all, twenty-four seamen were lost in the course of the voyage. The cargo brought back included more than 400 pounds' weight of gold, 36 butts of Guinea pepper, and 250 elephants’ tusks, as well as an elephant's skull of such size and weight that a man could scarcely lift it.[17][18][19][20] Lok's ships also brought home five Africans from present-day Ghana to learn English and act as interpreters on future trading voyages to Guinea.[21][22]

An account of the voyage was written by Robert Gaynsh or Gainsh, master of one of the ships.[19][23][24]

On 8 September certain articles were delivered to Lok by the London merchants Sir William Garrard, William Winter, Benjamin Gonson, Lok's brother-in-law, Anthony Hickman, and Edward Castelyn concerning another voyage to Guinea which they proposed to finance with Lok as captain. In a letter dated 11 December 1561 Lok declined to go, citing, among other reasons, the unsoundness of the ship and the unseasonableness of the time of year. The voyage went ahead without Lok in 1562; accounts were written in prose by William Rutter and in verse by Robert Baker.[25][26]

Lok is said to have died in France.[2] The date of his death is unknown.

Marriages and issue

Lok married Margaret Spert, cousin of Sir Thomas Spert,[27] but is said to have died without issue.[2]

Notes

- Lee 1893, p. 93.

- Locke 1853, pp. 358–9.

- Lowe 2004.

- McDermott 2004a.

- According to Lee she was the daughter of William Cooke of Salisbury, and at her death on 14 October 1537 was buried at Merton Priory in Surrey.

- Sutton 2005, p. 391.

- Dorothy Locke (d.1576+), A Who’s Who of Tudor Women: L compiled by Kathy Lynn Emerson to update and correct Wives and Daughters: The Women of Sixteenth-Century England (1984) Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Cosworth, John (by 1516-75), of London and Cosworth near St Columb, Cornwall, History of Parliament Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Sutton 2005, p. 559.

- Lock 2004.

- Brennan 2004.

- Grosart 1871, pp. 11-12.

- McDermott 2004.

- Elizabeth Locke or Lok (3 August 1535-c.1581), A Who’s Who of Tudor Women: L compiled by Kathy Lynn Emerson to update and correct Wives and Daughters: The Women of Sixteenth-Century England (1984) Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- According to McDermott, Elizabeth was William Lok's daughter by his first marriage; however according to Sutton Elizabeth was Rose Lok's youngest sister, and therefore William Lok's daughter by his second marriage.

- Hakluyt 1904, pp. 76–104.

- Voyage to Guinea in 1554 by Captain John Lok Retrieved 29 November 2013/

- Hunt 1842, p. 175.

- Murray 1818, pp. 149–50.

- Lardner 1830, pp. 225–6.

- Africans in British History Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 24 November 2013/

- The Slave Trade and Abolition: Timeline, English Heritage Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- Kerr 1824.

- Voyage to Guinea, 1554, WorldCat Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Hakluyt 1906, pp. 253–61.

- McDermott 2001, p. 449.

- Baldwin 2004.

References

- Baldwin, R.C.D. (2004). "Spert, Sir Thomas (d. 1541)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Brennan, Michael G. (2004). "Lok, Henry (d. in or after 1608)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16949. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Grosart, Alexander, ed. (1871). Poems by Henry Lok, Gentleman (1593-1597). Privately printed.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hakluyt, Richard (1904). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation. V. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons. pp. 76–104. Retrieved 29 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hakluyt, Richard (1906). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation. VI. Glasgow: James MacLehose and Sons. pp. 154–80, 253–7. Retrieved 28 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunt, Freeman (1842). The Merchants' Magazine and Commercial Review. VII. New York.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kerr, Robert (1824). A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels. VII. Edinburgh: William Blackwood. Retrieved 24 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lardner, Dionysius (1830). The Cabinet Encyclopedia: The History of Maritime and Inland Discovery. II. London: Longman Rees.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 34. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 93.

|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Lock, Julian (2004). "Bullingham, Nicholas (1511?–1576)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3917. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Locke, John Goodwin (1853). Booke of the Lockes. Boston: James Munroe and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lowe, Ben (2004). "Throckmorton, Rose (1526–1613)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/67979. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McDermott, James (2004). "Lok, Michael (c.1532–1620x22)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16950. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- McDermott, James (2004a). "Lok, Sir William (1480–1550)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16951. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McDermott, James (2001). Martin Frobisher: Elizabethan Privateer. Yale University Press. p. 449. ISBN 0-300-08380-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murray, Hugh (1818). Historical Account of the Discoveries and Travels in Africa. I (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sutton, Anne F. (2005). The Mercery of London: Trade, Goods and People, 1130-1578. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 9780754653318.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williamson, James A. (July 1914). "Michael Lok". Blackwood's Magazine: 58–72.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- 'The second voyage to Guinea set out by Sir George Barne, Sir John Yorke, Thomas Lok, Anthonie Hickman and Edward Castelin, in the yere 1554. The Captaine whereof was M. John Lok', in Hakluyt, Richard, The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation Retrieved 28 November 2013

- Map of Cape Barbas, Morocco Retrieved 24 November 2013

- Will of William Lok, Mercer and Alderman of London, proved 11 September 1550, PROB 11/33/331, National Archives Retrieved 24 November 2013

- Millar, Eric George, 'Narrative of Mrs Rose Throckmorton', The British Museum Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Feb., 1935), pp. 74-76 Retrieved 24 November 2013