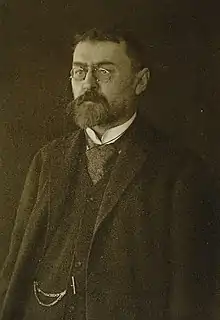

Jan Ludwik Popławski

Jan Ludwik Popławski (17 January 1854 in Bystrzejowice Pierwsze – 12 March 1908 in Warsaw) was a Polish journalist, author, politician and one of the first chief activists and ideologues of the right-wing National Democracy political camp.[1]

Jan Ludwik Popławski | |

|---|---|

Jan Ludwik Popławski | |

| Born | January 17, 1854 |

| Died | March 12, 1908 (aged 54) |

| Resting place | Powązki Cemetery |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

| Occupation | Journalist, author, politician |

| Spouse(s) | Felicja Potocka (since 1884) |

| Children | Janina, Wiktor |

Early life and education

Popławski entered the University of Warsaw in 1874. As a student he belonged to patriotic political organization Confederation of Polish Nation (Konfederacja Narodu Polskiego). In 1878 he was arrested by Russian authorities.[2]

Publications and ideology

Released in 1882, Popławski returned to Warsaw and began to write in the newspaper Prawda (Truth) under the pen name Wiat. From 1886, he worked for the weekly Głos (The Voice).

He was arrested in 1894 for participation in a protest commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) in Warsaw. In 1895 he was bailed out and released from Warsaw Citadel. Popławski eventually moved to Lwów, where together with Roman Dmowski published political magazine Przegląd Wszechpolski (The All-Poland Review), in 1897–1901 he was the sole editor-in-chief.[3] He later contributed to Wiek XX (20th century) daily and Słowo Polskie (The Polish Word).

Popławski was one of the main organizers of National-Democratic Party in the Austrian partition. From 1896 he edited a monthly publication called Polak (Pole) that was published in Kraków and aimed mainly at a peasant readership in the Russian partition.[3] He later became one of the founders of the Galician weekly Ojczyzna (Motherland).

One of the main ideas of his works was the issue of returning the Western lands to Poland, in particular Pomerania with the widest possible access to the Baltic Sea. Although focusing mostly on Western lands under Prussian partition, Popławski eventually also favoured inclusion of some Eastern territories to future independent Poland. He summarized these goals in 1901:

The country between the Oder and the Dnieper, between the Baltic and the Carpathians and the Black Sea, stands as a separate organic whole, a cohesive unity of territorial conditions, economic interests, and finally historical tradition.[4]

Popławski was also one of the most active social activists dealing with peasants' issues. Through his work and writings he elevated the awareness of poor village masses about their role in forming the modern Polish nation. Popławski understood that peasants were the backbone of national existence and the only basis for national regeneration.[5] In Popławski's view the ethnic heritage had little to do with nationality:

Being born or living on a certain territory and descending [from a certain] tribe not only cannot decide the nationality of thousands and millions of people, but not even a single person. Centuries of common political life, common spiritual and material culture, common interests, etc., mean one hundred times more than common descent or even language.[6]

After riots in Polish lands in 1905–1906, following the revolution of 1905, Popławski returned to Warsaw and took part in leadership of National Democratic movement. He joined the editorial staff of Gazeta Polska (Polish Daily) daily.

In 1907 he fell seriously ill and retreated from publishing. He was diagnosed with throat cancer.[3] Jan Ludwik Popławski died on 12 March 1908 in Warsaw.

Views on Jews

Popławski considered Jews to be "estranged" from the Poles as a result of the "features of the Semitic race".[7] Viewing the Jews as an alien body in the national Polish organism, Popławski wrote in his famous 1886 article that "Jewish apartness resists the melding of the Jews with the Poles into a unified national organism. The anti-Jewish movement in contemporary society is a pathology comparable to the way an organism fights against an alien body that has settled in it. This struggle ends either with the destruction of alien body, its repulsion, or the death of the organism".[8]

Works

- Stanisław Żółkiewski: Wielki hetman koronny (1903)

- Szkice literackie i naukowe (1910)

- Pisma polityczne (vol. 1–2, 1910)

- Wybór pism (1998)

Footnotes

- Bullen, Strandmann & Polonsky 1984, p. 130.

- Porter 1992, p. 640.

- Dobrowolski, Rafał (2004). "Jan Ludwik Popławski (1854–1908) – twórca myśli zachodniej". Nowa Myśl Polska (3): 16. Archived from the original on 2009-02-01.

- Popławski, Jan Ludwik: "Jubileusz pruski". In Pisma polityczne, Zygmunt Wasilewski (ed) (Kraków and Warsaw: Gebethner i Wolff, 1910), 1:240, as quoted in Porter 1992, p. 652.

- Suny & Kennedy 2001, p. 276.

- Popławski, Jan Ludwik: "Nasz demokratyzm". In Pisma polityczne, Zygmunt Wasilewski (ed) (Kraków and Warsaw: Gebethner i Wolff, 1910), 1:110, as quoted in Porter 1992, p. 646.

- Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism and the Jews of East Central Europe, edited by Michael L. Miller, Scott Ury, Routledge, page 97

- Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism and the Jews of East Central Europe, edited by Michael L. Miller, Scott Ury, Routledge

Bibliography

- Bullen, Roger J.; Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann; A. B. Polonsky, eds. (1984). Ideas into Politics: Aspects of European History, 1880–1950. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7099-0696-X.

- Porter, Brian A. (1992). "Who is a Pole and Where is Poland? Territory and Nation in the Rhetoric of Polish National Democracy before 1905". Slavic Review. 51 (4): 639–653. JSTOR 2500129.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Porter, Brian A. (2000). When Nationalism Began to Hate (PDF). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-13146-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-21. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor; Michael D. Kennedy (2001). Intellectuals and the Articulation of the Nation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08828-9.

Further reading

- Kulak, Teresa (1994). Jan Ludwik Popławski – biografia polityczna. Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. ISBN 83-04-04260-6.

External links

- (in Polish) Several texts of Jan Ludwik Popławski at Polskie Tradycje Intelektualne website