James T. McDermott (judge)

James T. McDermott (September 22, 1926 – June 21, 1992) was a Pennsylvania judge and politician who served on the state's Supreme Court from 1981 until his death in 1992. Before joining the court, he was active in Philadelphia politics as a Republican candidate for Congress in 1958, city council in 1962, and mayor in 1963. He was a trial court judge on the Court of Common Pleas from 1965 to 1981.

Early life and family

James Thomas McDermott, Sr., was born in Philadelphia in 1926, the son of Harry Aloysius McDermott and his wife Helen Genoe McDermott.[1][2] His maternal grandfather, James Genoe, was a Philadelphia Police captain, a fact later said to have contributed to McDermott's law-and-order approach on the bench.[3] His mother, Helen, was a vaudevillian singer and actress before her marriage and entertained the troops in World War I.[4] His father, a clerk and bartender, died in 1954.[2][5]

McDermott earned a bachelor's degree from Saint Joseph's University and a J.D. from Temple University Law School.[6] He was admitted to the bar in 1951 and practiced in the field of labor law at the firm he co-founded, McDermott, Quinn & Higgins.[7] He also taught classes on legal evidence at St. Joseph's and on commercial law at the American Institute of Banking.[7] In 1954, he married Mary Theresa Bradley; they remained married until her death in 1974 and had six children—five sons and one daughter.[8][9]

Political career

McDermott entered the political arena in 1958 when he ran for the Republican nomination for the federal House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 3rd district. He won the primary easily over William M. Phillips, a former city councilman, taking 85% of the vote.[10] In the general election that November, however, McDermott lost to the incumbent Democrat, James A. Byrne, by a 63.5% to 36.5% margin.[11]

In 1962, McDermott ran for city council at-large. The race was a special election, called when councilman Victor E. Moore resigned his seat to become head of the Philadelphia Gas Works in September 1962. Because of the short time between the vacancy and the election, ward leaders picked McDermott instead of holding a primary.[12] That November, McDermott lost the election to the executive director of the Philadelphia Parking Authority, Walter S. Pytko.[13]

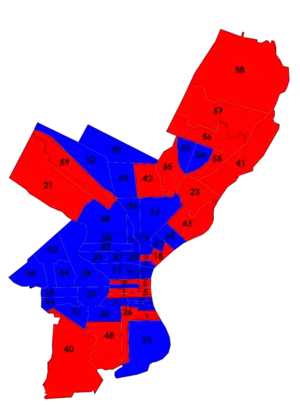

McDermott was the city Republican organization's choice for mayor in 1963, and he easily defeated three independent candidates in the May primary.[14] The Democrats nominated acting mayor James Hugh Joseph Tate for a full term, and a close race was expected.[15] McDermott campaigned on a reform platform, saying that Tate had worked to sabotage the good-government reforms of the Joseph S. Clark and Richardson Dilworth administrations that had run the city from 1951 to 1962.[16] Tate responded by contrasting his experience with McDermott's and touted his endorsement by the AFL–CIO.[16] McDermott said that Tate "has never been off the public payroll in twenty-five years" and criticized the mayor's refusal to debate him.[16] The election was closer than the one four years earlier, but McDermott still lost by more than 66,000 votes.[17][18]

Judicial career

McDermott continued his private law practice after his mayoral election defeat. In 1965, six new judicial positions were added in Philadelphia's division of the Court of Common Pleas, a trial court of general jurisdiction; Governor William Scranton named McDermott to one of them.[19] He and the other five new judges were nominated to full ten-year terms at the election that November. All six were endorsed by both parties and unopposed for retention in office.[20] He easily won another retention election ten years later, in 1975.[21] In his time on the bench, McDermott became known as a "hanging judge" who imposed harsh sentences on the criminals convicted in his court.[3][22] He imposed the death penalty thirteen times in his fifteen years as a trial court judge.[3]

In 1979, Mayor Frank Rizzo—then term-limited—encouraged McDermott to enter the mayor's race that year as an independent.[23] A few days later, McDermott took himself out of consideration, citing the tremendous cost of starting an independent campaign just two months before the election.[22]

Two years later, McDermott announced his candidacy for one of two open seats on the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. As was common with judicial races at the time, he ran for both major parties' nominations, but remained a member of the Republican Party.[24] He captured second place in the Republican primary—good enough to be nominated—and third on the Democratic slate—falling just short.[25] In the general election in November, McDermott took the top spot with his fellow Republican nominee, William D. Hutchinson, winning the second open seat.[26] The victories gave the Republican Party a 4-3 majority on the court.[26]

In 1983, the Philadelphia Inquirer published a series of stories accusing McDermott and other supreme court justices of conflicts of interest.[6] McDermott sued the newspaper for defamation and won a partial victory after a seven-week trial in 1990.[6] The following year, he won another ten-year term on the high court.[3] McDermott's $6 million verdict against the Inquirer was still being appealed when he died suddenly on June 21, 1992, at the age of 65.[6] After a funeral at St. Augustine Church, he was buried alongside his wife at Saints Peter and Paul Cemetery in Marple Township, Pennsylvania.[3]

References

- Marriage certificate 1924.

- 1930 Census.

- Ditzen 1992.

- Inquirer 1985.

- Death certificate 1954.

- Cass 1992.

- McFadden & Lynch 1958.

- Inquirer 1954.

- Inquirer 1974.

- Kohler 1958.

- Dubin 1998, p. 619.

- Inquirer 1962.

- Bulletin Almanac 1963.

- Miller 1963a.

- Miller 1963c.

- Miller 1963b.

- Miller 1963d.

- Bulletin Almanac 1964.

- Miller 1965.

- Inquirer 1965.

- Inquirer 1975.

- Taylor 1979.

- Frump & Odom 1979.

- Inquirer 1981.

- Biddle 1981a.

- Biddle 1981b.

Sources

Books

- Bulletin Almanac 1963. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Bulletin. 1963. OCLC 8641470.

- Bulletin Almanac 1964. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Bulletin. 1964. OCLC 8641470.

- Dubin, Michael J. (1998). United States Congressional elections, 1788–1997 : the official results of the elections of the 1st through 105th Congresses. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-0283-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Newspapers

- "Jottings Along the Social Way". The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 30, 1954. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kohler, Saul (May 21, 1958). "Nix's Double Victory in House Contest Blow To Clark". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFadden, James; Lynch, Robert Z. (October 30, 1958). "The Election: Here Are Your Candidates". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "GOP Selects 2 in Council Races". The Philadelphia Inquirer. September 22, 1962. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- Miller, Joseph H. (May 22, 1963a). "Regulars Score Easy Victories". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 5 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Joseph H. (September 29, 1963b). "AFL-CIO Backs Tate; He's Called Saboteur". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Joseph H. (November 3, 1963c). "Photo-Finish Predicted in Mayoralty Race Here". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Joseph H. (November 6, 1963d). "Tate Elected by 66,000-Vote Margin". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 3 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Joseph H. (July 31, 1965). "Scranton Picks Six Judges for Two New Courts". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 5 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "21 Unopposed Phila. Judges Elected to 10-Year Terms". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 3, 1965. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- "M. McDermott, Judge's Wife". The Philadelphia Inquirer. December 18, 1974. p. 2-E – via Newspapers.com.

- "Totals in Election". The Philadelphia Inquirer. November 5, 1975. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- Frump, Bob; Odom, Maida (August 8, 1979). "Enter race, Rizzo urges McDermott". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1-A, 2-A – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, Paul (August 17, 1979). "McDermott: Thanks, but no". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1-A, 2-A – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Judge McDermott to run for Penna. Supreme Court". The Philadelphia Inquirer. January 29, 1981. p. 2-G – via Newspapers.com.

- Biddle, Daniel R. (May 21, 1981a). "2 Western Pa. Democrats win Supreme Court primary". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 7-A – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Biddle, Daniel R. (November 5, 1981b). "McDermott wins seat on top Pa. court". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 1-A, 19-A – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Helen R. Jenoe McDermott". The Philadelphia Inquirer. July 4, 1985. p. 8-E – via Newspapers.com.

- Cass, Julia (June 22, 1992). "James T. McDermott, Pa. justice, dies at 65". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. 1, 2 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ditzen, L. Stewart (June 23, 1992). "J.T. McDermott, a tough justice who had a soft spot for literature". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Websites

- "Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Marriage Index, 1885–1951". Ancestry.com. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- "1930 United States Federal Census, T626, page 1B". Ancestry.com. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- "Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906-1967". Ancestry.com. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- Judge James T McDermott at Find a Grave