James Mackintosh Kennedy

James Mackintosh Kennedy (November 3, 1848 – August 14, 1922) was a Scottish-American poet, editor, and engineer.

James Mackintosh Kennedy | |

|---|---|

Kennedy, January 1, 1910. | |

| Born | November 3, 1848 Aberlemno, Angus, Scotland |

| Died | August 14, 1922 (aged 73) New York City, NY |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, NY |

| Occupation | Poet, editor, engineer |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Education | High school, literary course, with honors |

| Alma mater | New York Evening High School, New York, NY |

| Period | 1872-1922 |

| Genre | Scottish-American poetry, short stories, articles, character sketches, books |

| Subject | Poetry, engineering |

| Notable works | The Complete Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy |

| Notable awards | Official poet for 600th anniversary of Battle of Bannockburn |

| Spouse | Isabella Low Kennedy (married 1873-1910) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Early life and education in Scotland

James was born on Carsegownie Farm, Aberlemno, Forfarshire (now Angus), in Scotland. He was the seventh of ten children born to David Kennedy (1817-1853) and Jessie Mackintosh (1813-1901). David, a mason, was killed in a quarry blast[1] when James was five years old, leaving his widow with ten children of which four were under six years old. James attended the Parish School in Aberlemno for seven years, to age 12,[2] after which he was employed as a shepherd. The local Presbyterian church gave him textbooks, and he named his sheep after Greek philosophers.[1]

After a few years he moved to Dundee, studied in the high school,[3] and apprenticed as a machinist.[4][5] He "took a prominent part in the agitation of 1865 for improving the condition of the agricultural classes."[4]

While in Dundee, he began writing poetry and studying Scottish literature, and contributed poems to several publications.[4]

Believing that there were more opportunities for mechanics in the United States, James emigrated alone to New York City in 1868. He worked in locomotive shops around the country, returning to New York in 1872.[4]

Life in New York City

In 1872, James studied literature in the New York Evening High School, graduating with honors in 1875.[4][3][6][7] He continued studying oratory and Latin, and contributed to publications in Scotland and America.[4][7]

He was “one of the finest Highland dancers in New York,”[3] and from 1869 to 1878 won many medals.

He published his first book, Jock Craufurt,[8] a long romantic poem, in 1872 at age 23.

James married Isabella Low, a Scottish immigrant from Easter Clune near Aberdeen, on December 12, 1873. Their service was performed by Rev. Henry Ward Beecher.[4]

James’ and Isabella’s children were:

- Charles Kennedy (December 28, 1876)

- Isabella Washington Kennedy (February 22, 1879) (born on George Washington's birthday and named after him)

- Jessie Mackintosh Kennedy (April 23, 1881) (named after James' mother)

- Margaret Mortimer Kennedy (February 6, 1884) (named after Isabella's mother)

- Robert Buchanan Kennedy (August 23, 1885) (named after James’ good friend, Scottish poet Robert Buchanan - see Kennedy information on Buchanan site)

- Jean Low Kennedy (June 22, 1887) (named after James' paternal grandmother)

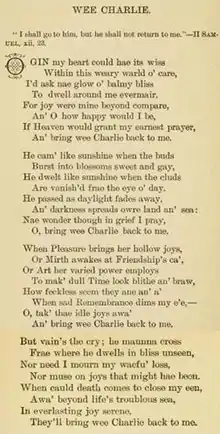

Their first child, Charles, was born in December, 1876. Isabella was born on February 22, in 1879. Just two and a half weeks later, Charles died. His father’s grief was expressed in a most moving poem, "Wee Charlie," below.

He often referred to his surviving children as “four lovely daughters and one promising son.”

James Kennedy became a U.S. citizen on October 16, 1886. The family lived at 233 East 109th Street in New York City from around 1884 to about 1916.

His wife Isabella died on November 7, 1910. After that he lived with his unmarried daughter Jean. Son Robert became a surgeon. He served with the medical corps of the New York National Guard in 1916, guarding the Rio Grande border with Mexico, where he contracted yellow fever. Robert died in June, 1917.

James had a close connection with the Scottish community in New York City, often being a speaker at clan meetings, and known for his humor. His friends included entertainer Harry Lauder and gynecologist Dr. Alexander Skene. He contributed frequently to the Scottish-American journal Caledonian.

In 1914 James was invited to be the official poet of the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn on June 24.[10] He traveled with his youngest daughter Jean, reading his commemorative poem to great acclaim at the battle site, and visiting Edinburgh and Dundee. Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated four days later, leading to World War I, and James and Jean cut their visit short and left Scotland on July 11.

James earned his living as an engineer, having charge of the locomotive shops of the New York Elevated railroad from 1879 until 1902,[11] and in 1883 superintending the construction of the first locomotive built at the shops.[3] He published The Valve Setter’s Guide[12] in 1910 (rev. 1914), and contributed to engineering literature: “Elements of Physical Science,” “Celebrated Engineers,” “Locomotive Running Repairs.”[2] He was an editor of Railway and Locomotive Engineering from 1905, becoming Vice President of the Angus Sinclair Publishing Company in 1917 and Editor-in-Chief and President in 1919, a position he held until his death in 1922. He was listed in Who’s Who in America, 1918-1919,[13] and in the American Literary Yearbook, 1919.

James was actively involved in New York City labor politics between 1902 and 1912, being president of the Harlem Republican Club for eight years, and running for Board of Aldermen, Assemblyman, and Senate.

James died suddenly on August 14, 1922,[3] at age 73, after an illness of 16 days. He had had failing health for six months.

Writings

James Mackintosh Kennedy was a keen observer of human nature and wrote with sympathy and humor. He was well-known and honored for his poetry, being selected as the official poet for the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1914.[10]

James Kennedy’s writings were published extensively in the Caledonian, a monthly journal for Scottish immigrants in the United States. His contributions included poetry, short stories, character sketches, and biographical articles.

Kennedy also published technical articles in Railway and Locomotive Engineering : A practical journal of railway motive power and rolling stock, published monthly by the Angus Sinclair Company, and a book on locomotive engineering. He became an associate editor for this journal in 1905 and became Editor-in-chief and President upon Sinclair’s death in 1919.[3]

Following is a list of books published by James Kennedy:

- 1872: Jock Craufurt: a poem in the Scottish dialect.[8] A long romantic poem.

- 1883: Poems, Songs and Lyrical Character Sketches.[14]

- 1883: Poems on Scottish and American Subjects.[15]

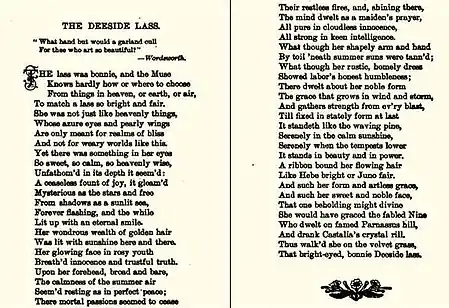

- 1888: The Deeside Lass, and Other Poems.[16] The long poem is the story of the laird’s son Donald who falls in love with the servant girl Jean who had been taken in as an orphan; the laird sees the virtues in Jean, but the laird’s wife is furious, and the pair run off.

- 1899: The Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy.[9]

- 1910: The valve setter's guide: A treatise on the construction and adjustment of the principal valve gearings used on American locomotives.[12]

- 1920: The Complete Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy.[17]

Most of these books are available online and/or in reprint. Several[15][9][12] are described as: "This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it."

A sampling of his poems is presented below.

Poem by James Mackintosh Kennedy. Scottish and American Poems,[9] pp. 165-166. |

Poem by James Mackintosh Kennedy. Scottish and American Poems,[9] pp. 55-56. |

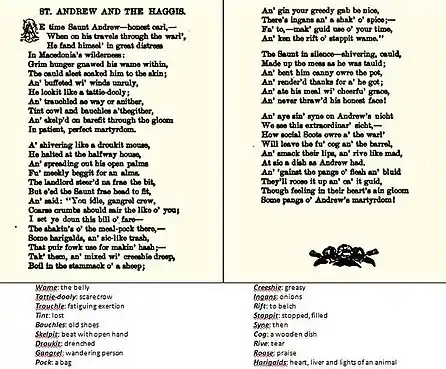

Poem by James Mackintosh Kennedy. Scottish and American Poems,[9] pp. 138-139. |

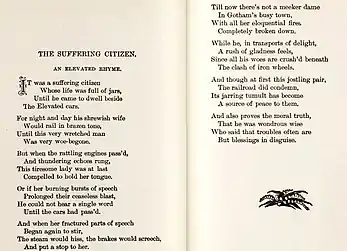

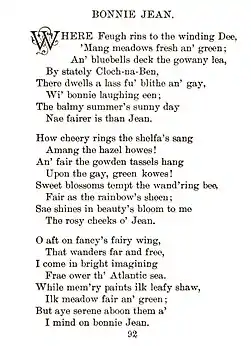

Poem by James Mackintosh Kennedy. Scottish and American Poems,[9] p. 92. |

Kennedy's family has annotated a collection of his letters (Letters to My Daughters: 1910-1916) and compiled a biographical document. Below is an excerpt from a letter by James Kennedy to his daughter Isabella, written August 15, 1901, on the subject of "husbandry."

| I know if I were a young American woman and had an education and 10 blessed weeks to myself every summer and every Saturday and every holiday to myself – I would like to see the man I would look at twice. He would have to be somebody. Doubtless the young man may be the son of some substantial man which is a great thing and in this regard I would rather hear that you had gone to Africa and was happy and comfortable than see you come back here and take up with some ordinary “snipe” and climb six pair of stairs and occupy two rooms back with a full view of 10 feet of a back yard and never a blessed day to yourself but drudgery and scraping and washing and worrying and wondering where the rent was to come from --

O! I could lecture all night on this subject and fill pages with illustrations, but your own imagination is sufficient. There can be no harm in asking you who was the noblest lady ever sat on the throne of England? It was Elizabeth Tudor! Why – because husbandry had no attraction for her. Who was the most disturbing woman that ever had any authority in the British Isles? It was Mary Stuart – Why – because her fondness for husbandry. Who is the finest lady in this city to-day, honored by everybody and blessed by thousands? Mrs. Asterbilt! No – Mrs. Croker – not at all – It is Helen Gould – Why – because she keeps aloof from husbandry. Who is the finest lady in this spot? I mean outside the Kennedy family – It is Miss Emma Shay! Why – because husbandry has no attraction for her. How serene she is! and how beautiful! And how rosy youth walks with her and dwells around her, and when Loretta with a wheelbarrowful of children comes you would not think they were sisters – why? – because husbandry has set its foot upon her and she is withering away! Who is the finest lady in the Lady Macduff Circle? Outside the Kennedy family – It is Aunt Mary – Why? – Because she steers clear of husbandry and her light-heart and merry laugh abide with her forever! Amen! |

References

- Barto, Ruth (2009). Family Memories. Unpublished.

- Kennedy, James (1915). Resume. Unpublished.

- In Memoriam: James Kennedy. Caledonian, September 1922, pp. 174-177.

- Ross, John D. (1889). Scottish Poets in America, with Biographical and Critical Notices. New York: Pagan & Ross, Publishers, pp. 38-46.

- Reid, Alan (1897). James Kennedy. The Bards of Angus and the Mearns: An Anthology of the Counties. Paisley: J. and R. Parlane, pp. 250-252.

- MacDougall, D. (Ed.) (1917). Scots and Scots' Descendants in America. New York: Caledonian Publishing Company, pp. 250-251.

- Edwards, David Herschell (1883). One Hundred Modern Scottish Poets: With Biographical and Critical Notices. Brechin: D. H. Edwards, pp. 213-222.

- Kennedy, James (1872). Jock Craufurt: a poem in the Scottish dialect. L.D. Robertson, New York.

- Kennedy, James (1899). The Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy. Ogilvie Publishing Company, New York; 1883, 1888, 1899; revised edition, 1907; revised and enlarged edition, Oliphant, Edinburgh.

- A BANNOCKBURN POEM.; James Kennedy of New York Reads Verses on 600th Anniversary. The New York Times, July 12, 1914.

- James Kennedy Dead. The New York Times, August 16, 1922.

- Kennedy, James (1910). The valve setter's guide: A treatise on the construction and adjustment of the principal valve gearings used on American locomotives. Angus Sinclair Company, New York.

- Who’s Who in America, 1918-1919, Vol. X. Chicago: A. N. Marquis & Co., p. 1514.

- Kennedy, James (1883). Poems, Songs and Lyrical Character Sketches. L.D. & J.A. Robertson, New York.

- Kennedy, James (1883). Poems on Scottish and American Subjects. L.D. & J.A. Robertson, New York; Edinburgh; Glasgow; London.

- Kennedy, James (1888). The Deeside Lass, and Other Poems. Cormack & Co, Aberdeen.

- Kennedy, James (1920). The Complete Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy. Ogilvie Publishing Company, New York.