James Havard Thomas

James Havard Thomas (22 December 1854 – 6 June 1921) was a Welsh sculptor active in London and Capri. He became the first Chair of Sculpture at the Slade School of Art in London. He was known for his painstakingly precise sculptures resulting from elaborate and time-consuming processes for achieving sculptural realism. He emerged from the same roots as the "New Sculpture" in Britain, and his career runs parallel to (and in dialogue with) that movement.

Biography

Thomas first studied at the Bristol School of Art, then at South Kensington. He first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1872. In 1879, he went to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts under Pierre-Jules Cavelier. In 1885, he exhibited his marble statue Slave Girl to much acclaim in London.[1]

Thomas was associated with the New English Art Club and its attempts to reform the Royal Academy of Arts. In 1887-88, he served as Secretary for the Provisional Committee for Securing a Suffrage in the National Exhibition of the Arts, and this prominent role insured that Thomas would never be elected to the Royal Academy for the remainder of his career.[2]

Soon after the failed attempt to reform the academicians, in 1889, Thomas departed for Italy. He lived in Naples, Valle di Pompeii, and, most extensively, Capri, where he studied the lives of peasants, while also designing a system by which he could accurately determine the three-dimensional representation of the human form. He became a fixture of the expatriate community in Capri, and he was the inspiration for the character of Count Caloveglia in Norman Douglas's novel South Wind (1917).[3]

In keeping with his disdain for the Royal Academy, Thomas repudiated the techniques of academic sculpture. Instead, he developed an elaborate system to accurately measure the complex topography of the human body and to translate it into a three-dimensional medium. Taxingly for his models, Thomas would take weeks to minutely map the human body using an armature that allowed him to translate the complex forms into a numerical system which, in turn, allowed it to be recreated in a sculptural material (his preference came to be wax over mahogany).[4]

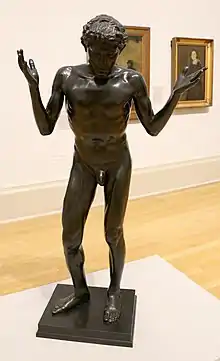

Thomas resettled in London in 1906. Upon returning to Britain, his statue Lycidas (1905) was intended as an exemplar of his hard-won method. A complex and awkward statue, it aimed to reproduce exactly the body of his model, a Pompeiian named Antonio. It eschewed traditional compositional rules and the standard techniques sculptors used to pose and to render human bodies. Thomas deliberately made the work resistant to interpretation of its symbolism, gesture, or expressivity. Norman Douglas claimed to have suggested the name to Thomas so as to "convey no definite suggestion; he wanted something vague and yet distinguished. I hit upon Lycidas because it belonged to three or four persons in antiquity, none of any great importance."[5] The statue was both unorthodox and rigorously Classical. It created a scandal when it was rejected by the Royal Academy in 1905. The sculptor Hamo Thornycroft — a contemporary of Thomas's and a long-standing academician whose innovations of the 1880s had calcified into a conservative narrowness by the twentieth century — was most likely instrumental in the statue's rejection.[6] One newspaper described the rejection as "one of the most scandalous infringements of [the Royal Academy's] public duty of which they have ever been convicted."[7] Lycidas was instead shown at the New Gallery in London and became a symbol of the renewed desire to reform the Royal Academy. This cemented Thomas's reputation as an alternative to the Academy, leading in a few years to his invitation to teach sculpture at the Slade School of Art in 1911 and being named as its first Chair of Sculpture in 1914.

Thomas was instrumental in teaching a generation of women sculptors working with direct carving: at the Slade his students included Dora Clarke, H. W. Palliser, and Ursula Edgcumbe.

Thomas was an important foundation for the development of modernism in British sculpture, and his work contributed to the interest in direct carving and to the break with the expectations of the statuary tradition. Jacob Epstein, for instance, sought out Thomas soon after he moved to England. Roger Fry purchased a relief sculpture for the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and Michael Sadler purchased versions of Lycidas for Manchester and for the Tate.[8] Though overlooked today, Thomas was a significant player in the debates around sculptural representation and the modernization of the Classical tradition in the early twentieth century.

Bibliography

Clausen, George. "James Havard Thomas." In Memorial Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by the Late J. Havard Thomas (1845–1921). London: Leicester Galleries, 1922, 5–10.

Douglas, Norman. Late Harvest. London: Lindsey Drummond, 1946.

Getsy, David. Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004. Chapter 5: "Figural Equivalence and Equivocation: James Havard Thomas and the Lycidas 'Scandal' of 1905"

Gibson, Frank. "The Sculpture of Professor James Havard Thomas." The Studio 76, no. 313 (1919): 79–85

MacColl, D.S. "Lycidas." Saturday Review (29 April 1905)

Pearson, Fiona. "The Correspondence between P.H. Emerson and J. Havard Thomas." In M. Weaver, ed., British Photography in the Nineteenth Century: The Fine Art Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989, 197–204.

References

- Pearson, Fiona (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (entry: James Havard Thomas). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198614128.

- Getsy, David (2004). Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 141–71. ISBN 0300105126.

- Douglas, Norman (1924). South Wind. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780198614128.

- Getsy, David (2004). Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. p. 153. ISBN 0-300-10512-6.

- Douglas, Norman (1946). Late Harvest. London: Lindsay Drummond. p. 59. ISBN 0404147178.

- Getsy, David (2004). Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 158–59. ISBN 0300105126.

- A.J.F. (26 April 1905). "The Rejected of the Academy". The Morning Leader. quoted in Getsy 2004, p. 159.

- Getsy, David (2004). Body Doubles: Sculpture in Britain, 1877–1905. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 141–71. ISBN 0300105126.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to James Havard Thomas. |