J. Lee Nicholson

Jerome Lee (J. Lee) Nicholson (1863 - November 2, 1924) was an American accountant, industrial consultant, author and educator[1] at the New York University and Columbia University,[2] known as pioneer in cost accounting. He is considered in the United States to be the "father of cost accounting."[3][4]

Nicholson most important contributions to cost accounting consisted of "emphasizing cost centres and the measuring of profits for individual departments based on machine hour rates."[5] Also he helped establishing the National Association of Cost Accountants (NACA) in 1920, which resulted into the Institute of Management Accountants.[6]

Biography

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, Nicholson grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[4] After attending common school and business college, he started in industry. In his spare time he studied accountancy, and eventually in 1901 he obtained his Certified Public Accountant license for the State of New York.[7]

Nicholson had started his career at the Keystone Bridge Company, where he worked his way up from office boy to assistant at the engineering department. In drawing up plans for the company foreman and superintendent, he started to develop his interest in cost accounting. At the age of 21, in 1884, he moved to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company where he had obtained an accounting position.[2] Around 1900 Nicholson started his own accountancy and consultancy firm J. Lee Nicholson and Company, specialized in cost systems for manufacturing organizations.[2]

During World War I he served at the US Ordnance Department as supervising cost accountant in 1917–18. He was promoted to the rank of Major,[8] and kept using his rank in public life, signed his work with Major J. Lee Nicholson, and is remembered by that name.[9][10] Previous to this position at the Ordnance Department, he was chief of the Division of Cost Accounting of the Department of Commerce. The filling of these positions gave him ample opportunity to become familiar with the war contract situation in its accounting aspects. In the summer of 1917 he was chairman of a conference of delegates from the War, Navy, and Commerce Departments, the Federal Trade Commission, and the Council of National Defense. This conference, in a pamphlet issued July 81, 1917, made certain recommendations regarding government contracts, and these recommendations are presented verbatim in Nicholson and Rohrbach's Cost Accounting (1919).[11]

.jpg.webp)

Nicholson has been active in accountancy societies since the early 1900s. He joined the New York State Society of CPAs in 1902, where he became its first vice-president, and served as its president. In 1906 he also joined the American Association of Public Accountants. In 1920 Nicholson was founding president[12][13] of the National Association of Cost Accountants (NACA) founded in Buffalo, N.Y., the forerunner of the Institute of Management Accountants [14]

Nicholson authored several books, including "Nicholson on Factory Organization and Costs" published in 1909, "Cost Accounting Theory and Practice" in 1913, and "Cost Accounting" in 1920 and several papers. All three books were published in multiple editions.

Due to his ill-health he retired and moved to California in 1922, where two years later he died suddenly November 2, 1924 in San Francisco.[4][15]

Work

Early 20th century, when Nicholson started published his first work, the development towards modern cost accounting was well underway for two decades. Chatfield (2014) summarized that "After hundreds of years of painfully slow progress, cost accounting took off during the 1880s. Between 1885 and 1920, the essentials of modern cost technique were formulated and to some extent standardized in practice. Workable overhead allocation methods were devised, procedures were developed for integrating cost and financial accounts, and standard costing became routinized."[1]

Chandra and Paperman (1976) specified, that "serious studies in cost accounting started only in the 1890s with the writings of Metcalfe, Garcke and Fells, Norton, Lewis, and later with Church, Nicholson and Clark. They were truly the pioneers who introduced new cost concepts like fixed and variable costs, standard cost, cost centers, relevant costs, etc. in the literature. The development of cost accounting in this period was undoubtedly slow. In addition, cost accounting tried to adapt itself within the framework of financial accounting. Part of the delay in the establishment of cost accounting concepts may be due to the tendency of cost accountants to keep the methods they had developed within their own firms secret."[16][17] Nicholson and Rohrbach (1919) specified that most work on cost accounting was written in the last decade, stating that "more than 90% of this literature has been published in the last decade, and fully 75% in the last five years."[18]

More specific about Nicholson's role Chatfield (2014) noticed, that "Nicholson was less an innovator than a synthesizer. His main contribution was to organize, improve, and propagate this new knowledge as it spread from a tiny minority of pioneering firms to the vast majority of manufacturers who still had no formal cost accounting systems at the beginning of the twentieth century."[1]

Purpose

In 1909 Nicholson published his first book, entitled "Nicholson in Factory Organization and Costs". In the preview he explained, that this work was primarily intended as a handbook for manufacturers, who are interested in "modern methods of organization and systems"; for accountants and cost specialists as a book of reference; and also as a textbook on cost accounting for the student.[19]

It was also Nicholson intention to outline and explain all the best known methods of Factory Organization, that relate to Cost Finding in such a manner as to enable the manufacturer to compare these methods with those in use in his own plant, in order that he may see more clearly the defects in his organization and how to remedy them. Nicholson hoped that the Public Accountant, Systematizer, and Cost Clerk would find this work to be of value as a reference in planning, devising, or changing a factory system.[19]

Content

The work contains forty-eight chapters. Among other important topics "Organization and Cost Finding" forms the subject of one chapter. In this chapter the author summarizes the most important arguments for and against cost systems; he also shows the effect of cost system on organization, independent of cost finding, pointing out clearly the value of system to management. The second important topic dealt with is " Wage Systems." Under this head the author points out the general relation of wage systems to costs, treating of the pay-rate-system, piece work and the differential rate plan, as well as profit-sharing and stock-distribution.

The author then discusses the "Analysis of Cost Accounting," pointing out the fallacy of including selling and administrative expenses in factory costs; also criticisms of incorrect principles in distributing overhead charges. He then deals with the distribution of indirect expenses and explains the old machine rate, new machine rate, fixed machine rate, new pay rate, etc.[20]

The fifth and sixth chapters constitute a general introduction to the subject of forms and systems and discuss such topics as principles used in forms and systems, estimated cost systems, actual cost systems, the designs and explanations relating to the conditions under which forms should be used.[20]

Chapters seven to forty-two contain a large variety of forms (over 200). While undoubtedly a number of these forms or similar ones are to be found in ordinary treatises, nevertheless a good many, if not the majority of them, are original and have evidently been taken from actual experience. The author elucidates and fully explains the use of all the forms given and the advantages that can be derived from them. The forms are in large clear type and well arranged. And finally, the last chapters treat of mechanical office appliances.

Analyses of cost accounting

In the third chapter Nicholson described, that in his days there was still a significant lack of knowledge on the subject of factory costs. Although the importance and desirability of accurate methods of ascertaining the cost of production is generally conceded, and while much attention has been devoted to this subject, and large sums of money expended annually in perfecting cost keeping records, there is a general lack of knowledge in many instances of the principles involved; and the problem now in hand is to present an analysis of the elements that go to make cost, and to indicate the lines along which methods must be devised to gather and classify the facts that are used in its actual determination. The accuracy and effectiveness with which this is done rests on, (1) the principles involved, and (2) the methods used.[21]

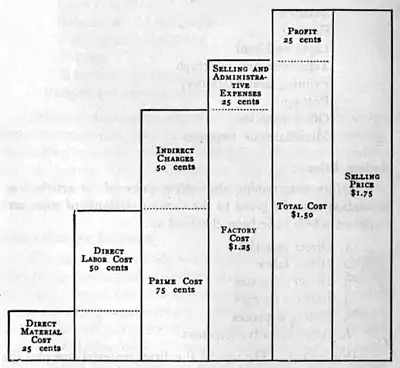

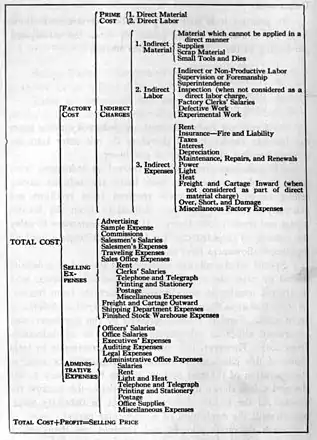

Nicholson explained, that the elements that comprise the cost in all manufacturing enterprises are made up of three principal divisions:[21]

- Material : Direct material is that element of material that enters into the product itself and can be charged accurately to the article. Indirect material consists of such material as factory supplies used in the processes, but which do not enter into the product itself. These cannot be charged directly to any one article, but must be distributed over the number of articles affected by their use.[21]

- Labor : direct labor is limited to that labor which is actually expended on producing the article manufactured. All forms of labor, such as repairing, hand ling, supervising, etc., that are not engaged directly on the article itself, are desig nated as indirect labor. As in the case of indirect material, the expense of this non-productive labor is distributed over that part of the production that is indirectly affected by it.[21]

- Indirect Expense : Indirect expense, together with indirect material and indirect labor, compose the last element of Cost, which is sometimes called "Burden" and sometimes "Overhead "; and this large element of cost must be distributed accurately, by some known ratio, over the production^ if correct costs are to be obtained.[21]

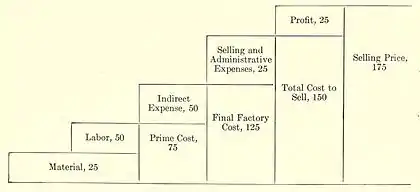

The elements, that comprise the cost can be graphically depicted (see image). Beside the here three listed principal divisions, it mentions the selling and administrative expenses, together compromising the total expenses.

Forms and systems for control of operations

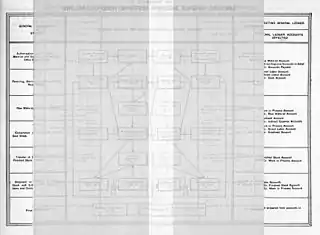

The biggest part of Nicholson in Factory Organization and Costs, is devoted the description of a control system of operations, which relies on a series of forms, and accompanying procedures. Nicholson explained:

CHAPTERS VII to XXXI, inclusive, are devoted to the explanation and illustration of the various forms which may be introduced in a manufacturing business. The forms shown are in most cases similar to forms that are to-day in successful operation in factory systems that have been devised by the author. These forms have been used in a number of plants manufacturing different products, and it is believed that in their entirety they cover most of the important conditions which will be found to exist in any one plant.

This does not mean that these forms are submitted to the business man or accountant as being absolutely orthodox in design and admitting of no change. No one form is adaptable to all lines of manufacture or accounting, and even in the same line of business the same form cannot be used successfully in every instance, as the volume of business, the conditions of manufacture, and the policy of the management, so far as the plan of organization is involved, would make this impracticable...[22]

The forms and designs were to be used in connection with the several systems in the Factory Organization. Nicholson introduced three of these systems in advance as follows:

- ESTIMATED COST SYSTEMS : In order to assist those who, instead of using an actual cost system, estimate their costs and keep their general accounts in the books in such a way as to make it difficult to form any opinion as to the accuracy of these estimates at the end of the year or at any other time, several methods calculated to aid in such case will be found in the chapters on this subject...[23]

- ACTUAL COST SYSTEM : The importance of this subject, while being generally conceded, is nevertheless sadly neglected, and the only explanation that can be given is that either the business man and his assistants are not able to inaugurate such a system, or the expense that might be involved prevents him from taking any action in this direction. This is the only logical explanation that can be offered where the importance of the matter is conceded and admits of no argument or difference of opinion...[24]

- STOCK SYSTEM : Although it is not necessary to inaugurate a perpetual inventory in order to obtain costs, yet it is advisable to do so whenever possible, as a safeguard to prevent waste of material, theft, or losses from any other causes; and also to guard against over-buying or failure to carry in stock such materials as are neces sary for the operation of the plant...[25]

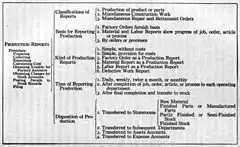

The whole series of forms presented in the work is summarized in a single sheet (see image). They are presented in 24 classes, covering operations from purchasing, material handling, stock keeping, time tickets, and production records, to cost records, further accounting operations, to drawing patterns and monthly reports. It showed building blocks of the information architecture.

Classification of factory accounts

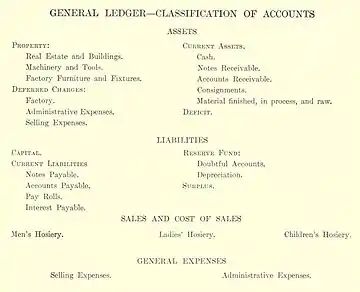

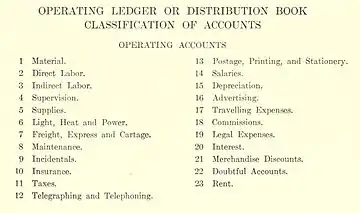

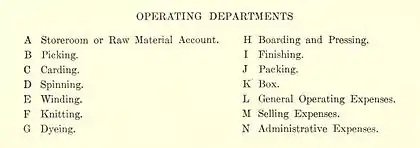

As mentioned in the introduction, Nicholson helped standardize cost accounting practice,"[1] and contributed to the introduction of standard costing.[16] A basic building block in this effort is the classification of the accounting practices and factory procedures and reporting. Nicholson kept developing these classifications in his 1909, 1913 and 1919 books. In his 1909 "Factory Organization and Costs" he introduced the classification of the general ledger and of the operating ledger:

- Classification of factory accounts and organization, 1909

Classification of General ledger accounts

Classification of General ledger accounts Classification of Operating ledger accounts

Classification of Operating ledger accounts

Nicholson (1909) explained, that the first question to be considered in designing a system is the results to be obtained. If the system is to be a complete one, these results will ultimately be shown in the general accounts, which are usually contained in a General Ledger.[26]

- These accounts should be so classified as to show both the financial status and earnings of an enterprise. The proper classification and arrangement of these accounts will affect to a great extent the accuracy and clearness of the results to be obtained.

- It is not necessary in the case of a small enterprise to have an elaborate or extensive classification of accounts. A few will answer all purposes in such cases, providing that the purpose of each account is well defined and charges and credits to these accounts during the year are properly made.

The accounts, however, must be so kept and arranged as to admit of showing proper results, either at the end of the year or monthly, according to the general plan of the system.[26] Additional to the classification of general and operating ledger, Nicholson gave a classification of operating departments (see image).

Nicholson (1909) continued, that in the classification of accounts herein set forth, it will be observed that the assets appear under three principal classifications namely:[26]

- Property, the fixed assets of the enterprise, and by this term is meant assets that cannot readily be converted into cash.

- Deferred Charges, expenses chargeable to future operations of any nature whatever, such as unexpired insurance, prepaid interest, unusual advertising charges, catalogue expenses, or any other expenses that should not be entirely charged off during any one period but should be pro-rated over several months or fiscal periods. This can be done by charging the original amount to any account properly named under this classification, and by writing off or credit ingto this account the proper proportion each month, charging the amount thus written off to some suitable expense account.

- Current Assets, assets of a nature that may be termed quick assets, which can be realized upon currently or from time to time, and are intended to represent the accounts from which funds can be derived to meet current liabilities.

Nicholson (1909) continued to explain the ins and out of Accounts Receivable, the Consignment Account, the Factory Account (inventory of raw material as well as finished stock and goods in process of manufacture), Liabilities, Current Liabilities, Sales, Cost of Sales, etc.[27]

Office appliances

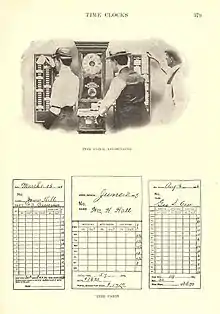

About the last sixty pages of his 1909 work, Nicholson devotes to a treatment of mechanical office appliances, giving illustrations of such appliances and explaining fully the use of each one.[20] Nicholson explained that the purpose of chapter was to present information to the manufacturer which may aid him in the organization of his office and in the handling of the immense detail connected with the majority of manufacturing plants. He argued, that "the clerk hire generally necessary in the office of a large plant acts as a dead weight on the profits, and any device which promises to lighten this burden on the cost of production is at least worth careful consideration."[28]

Nicholson made clear, that the general purpose of mechanical office devices are to lessen the indirect expenses of a factory, and as such clearly within the scope of a book on Factory Costs. The use of these devices would bring four distinct advantages:[28]

- They save time in collecting, arranging, and calculating the different items that must be handled in office management: To illustrate this it is only necessary to refer to the function of those time stamps and clocks which register the time of employees on cards in such a way that the computation of the week s pay is only a matter of a short addition and easy multiplication. If wage tables are used even this is dispensed with, as there is then no necessity for the double handling of time records, a feature of the ordinary methods of computing pay rolls. In collecting data for finding costs, the time of beginning and completing operations is usually registered on cards by the workman himself in writing. The use of time stamps in the factory effects a considerable saving of time in this respect alone.[28]

- They obtain greater accuracy with less labor incurred. Calculating machines gain in accuracy by reason of eliminating the personal equation in the operation itself, etc.[28]

- Through their use the clerical force may be reduced, either in actual difference in numbers or in the class of clerks hired: That is to say that the man agement may often substitute a machine, with a clerk of ordinary intelligence and moderate pay, for the skilled employee whose wages are necessarily high.[28]

- They arrange the work in better form for inspection and use than do the old pen and ink methods. The printed tabular forms and loose sheet devices are surely easier to deal with than cumbersome books and written columns, which have been used from remote times in the accounts of manufacturing firms.[28]

The presentation of these kind of office appliances was more common in management books in those days. Richard T. Dana (1876-1928) and Halbert Powers Gillette devoted a substantial part of their (1909) Construction Cost Keeping and Management to the description of numerous office appliances.

Reception

A 1909 review in the Journal of Accountancy judged, that the work was the "first American treatise on cost accounting proper, dealing with the subject from an accountant's point of view."[29] The review continues: "The author, though keeping to the front in his treatment of important accounting principles applicable to the subject, has nevertheless written the book in clear and untechnical language... While it may be questioned whether the author has been successful in preparing a text-book for students, he has undoubtedly accomplished his prime object, that of supplying the manufacturer with a thorough treatise on a subject in which he is vitally interested, and that of giving professional accountants and cost specialists a valuable reference work."[20]

Taylor (1979) recalled, that this 1909 work was the first presentation of a "unified treatment of the estimated cost system." Four years later Nicholson published his second book, Cost Accounting Theory and Practice, which described the "same methods for determining inventories, cost estimates, and analysis of cost of sales but he varied his verification technique."[2]

Cost Accounting Theory and Practice, 1913

In 1913 Nicholson published Cost Accounting Theory and Practice. In this work he presented "the same methods for determining inventories, cost estimates, and analysis of cost of sales but he varied his verification technique. This book probably shows the results of his teaching experiences at New York and Columbia Universities. Mr. Nicholson also recommends, in this book, a method for estimating cost of sales at current prices which foreshadowed LIFO accounting."[2] Hein (1959) specified:

One of the most remarkable developments in this volume is his distinction between operating departments and service or indirect departments with respect to the allocation of overhead. Another historically important contribution is the integration of the factory accounting with the general financial ledger through the use of reciprocal accounts.

But Nicholson went well beyond the treatment of "what are costs" and "how to account for costs." He was deeply interested in factory organization as such, and in the relationship of the cost department with the other departments in a company. The reader can infer this emphasis from the "factory organization" part of the title of his first book. A large part of his consulting practice was devoted to problems of organization and management.[30]

Newlove (1975) mentioned that this work was a very famous textbook, which "devoted four chapters to the allocation of burden costs to the special factory orders or to the product on its productive labor and machine (or process) methods; this emphasis greatly exceeded the space devoted to the collection, analysis and control of burden."[31]

System of factory accounting

In the late 1880s Garcke and Fells, had developed a system of factory accounting, and pictured its elements in four complementary flow diagrams. In 1896 J. Slater Lewis further developed this system, and pictured a diagram of manufacturing accounts, in which the four diagrams were integrated into one whole. A decennium later Alexander Hamilton Church (1908/10) would further develop this system by introducing the concept of production factors, and picturing the "Principles of Organization by Production Factors" around any organization. Using this concept of production factors Church was able to simplify the system of manufacturing accounts to a "Systems of Controlling Accounts."

In the 1913 Cost accounting Nicholson & Rohrbach presented not one, but four different method of factory accounting:

- Special Order System, Productive Labor Method (see image, which only shows some fragments)[32]

- Special Order System, Process or Machine Method[33]

- Product System, Productive Labor Method,[34] and

- Product System, Process or Machine Method.[35]

In the same year Nicholson & Rohrbach published their work, in 1913/19, Edward P. Moxey published his influential textbook on accountancy, in which he also pictured the relation of stores records to commercial records.

In his 1922 Cost accounts George Hillis Newlove further multiple similar Special Order Systems (see images).[36]

- Chart Showing Books under Special Order Cost System, 1922

Special Order Cost System Not Using Separate Factory Ledger, 1922

Special Order Cost System Not Using Separate Factory Ledger, 1922 Special Order Cost System Using Separate Factory Ledger, 1922

Special Order Cost System Using Separate Factory Ledger, 1922

Interest costs

Previts (1974) shared Nicholson among the foremost pioneers of interest costs, with William Morse Cole, John R. Wildman, DR Scott, D. C. Eggleston, Thomas H. Sanders and G. Charter Harrison. According to Previts "the early arguments over treatment of interest cost (both paid and imputed) spurred publication of countless articles and commentaries along with a relatively sound but since unheralded work Interest as a Cost..."[37] Nicholson explained his point of view in this matter in the 1913 article "Interest Should be Included as Part of the Cost" in the Journal of Accountancy in which he started the following argument:

The writer firmly believes in the theory that interest on capital invested should be charged to the proper expense accounts before ascertaining the actual profit from manufacturing or trading.

There is a large difference in risk between capital invested in stocks, bonds and real estate and capital invested in manufacturing or other commercial undertakings; and it is not to be disputed that capital invested in commercial enterprises is liable to far greater risk than that of capital invested in securities. It is only fair that the capital invested in commercial enterprises should have credit for at least the same return as that in securities before a trading profit is shown.

The two articles in the April number of The Journal by Wm. Morse Cole and A. Hamilton Church give such logical reasons for the inclusion of interest as a part of the cost...[38]

Previts (1974) further explained, that the opposition consisted of a "politically more prominent group, and in the sense of the outcome, the success of their position may have been in large part because of such political strength. As early as 1911, Arthur Lowes Dickinson criticized advocates of interest inclusion. Dickinson's allies included R. H. Montgomery, Jos. F. Sterrett, and George O. May."[37]

In the 1919 Cost Accounting Nicholson and Rohrbach again deal with the admittedly controversial question as to whether it is proper to treat normal interest return on passive investment as a part of manufacturing costs, the position is taken that interest on fixed assets should be so charged, but not interest on floating capital investment. The charging of some interest item is considered necessary to the successful distribution of overhead. Or, more exactly, normal return on passive investment is regarded as overhead to be distributed among the factory products. The authors in chapter IV considers that the opposition argument is directed chiefly at the practice of making these charges as part of the regular costs, not at the mere calculation thereof for use in statistical report form in the quotation of prices. He therefore suggests (p. 140) an accounting procedure supposed to meet this objection.[11]

The opposition view in that time was presented by William Andrew Paton and Russell Alger Stevenson in their Principles of Accounting (1919). To these writers, interest charges, whether contractual or non-contractual, are distribution-of-income, not expense, items. But, they say, if these charges are to be made at all, the logical procedure would be to distribute among the factory products the normal return on all the capital invested, not that on the fixed assets only. With this last contention, at least, the reviewer is inclined to agree. But Professors Paton and Stevenson appear to believe that the problem in hand is being solved on other than logical ground. For they say: "The use of interest charges in cost accounts on anything like a rational basis is a procedure which faces almost insurmountable practical obstacles. It is probably this fact rather than the logic of the case that is causing cost accountants to begin to recover from the interest obsession" [11][39]

Uniform cost accounting

Nicholson has been recognized as a proponent of uniform cost accounting. According to Gerald Berk (1997) Nicholson was part of a group of "associationalists", which promoted the idea that "uniform cost accounting, not enforcement, was the best hope to channel competition away from cut throat pricing into product and manufacturing process improvement."[40]

These proponents also assumed, that uniform cost accounting would increase factory efficiency. The general idea for manufacturers was, that "the more they would think systematically about 'planning, routing, and scheduling' conversion processes within the firm... the more they [would] understood about the cost of the many products they made, the more they could distinguish the profitable from the unprofitable."[40] In this context Nicholson had argued:

If a manufacturer can not make money in competition with other concerns when using the same methods of figuring costs, he can only conclude that his goods or his marketing, or both of them, are costing him too much. His next step, naturally, is to analyse closely the methods and conditions under which he is manufacturing and marketing his product, until he finds and corrects the inefficiencies which are handicapping him so seriously...[41]

In their 1919 "Cost Accounting" Nicholson and Rohrbach expressed the idea, that "if the accuracy of the cost estimate has been tested and the sales price of the product has been properly determined on the basis of the tested cost estimates, then the proper profit margin of the product sold would be assured. The objectives of estimate-cost accounting... were to assure proper profit for the products sold and to test their manufacturing costs in detail."[42]

National Association of Cost Accountants

In 1919 Nicholson conceived and organized the National Association of Cost Accountants.[43] For a start he had initiated a special meeting of the American Institute of Accountants to talk about the subject of cost accounting in manufacturing industries. This meeting was held October 13, 1919 in Buffalo, N.Y., and let to the founding of the National Association of Cost Accountants (NACA), forerunner of the Institute of Management Accountants.[14]

A total of 37 accountants attended the meeting, and among them were practitioners as William B. Castenholz, Stephen Gilman, Harry Dudley Greeley, and Clinton H. Scovell and professor of accounting Edward P. Moxey Jr. A total of 97 charter members joined in the initial organization, and among them were Arthur E. Andersen, Eric A. Camman, Frederick H. Hurdman, William M. Lybrand of Coopers & Lybrand, Robert Hiester Montgomery, C. Oliver Wellington, and John Raymond Wildman.[14]

Nicholson was elected its first President 1919–1920. He was succeeded by William M. Lybrand. In the Presidents report in the first Year book of the National Association of Cost Accountants, Nicholson explained, that the Association had started with 88 Chartered members. In the first year an additional 2.000 applications for membership had been received.[44]

State of the art of cost accounting

In the preface of the 1919 Cost Accounting Nicholson and Rohrbach gave their view on the state of the art of cost accounting in the United States.

Cost accounting, as a vital factor of successful business administration, has, in the last few years, been brought home in various ways to many manufacturers who before had never seriously appreciated its importance.

The Federal Trade Commission, working for more stable conditions, has conducted a widespread campaign of education, explaining in detail what a cost accounting system is, how it is operated, and the resulting business advantages.

Various manufacturers' associations have first paid skilled accountants to devise cost-finding methods suited to their special trade conditions, and then have instituted a vigorous propaganda to induce all engaged in their own particular industry to adopt them, thus making these methods uniform in the trade and securing uniformity of selling prices and the end of reckless and ignorant price-cutting.

Now the government, with its need to levy war taxes and its consequent necessity for searching investigation into income and excess profits, requires that estimates and approximations as to production costs and profits shall give place to rational accounting systems giving actual figures by uniform methods.[45]

One of the important aims of the book is to "classify the details of cost accounting so that the reader, be he accountant, manufacturer, or student, is given a well-defined idea of the forms and records required for each separate operation."[46]

Content of Costs accounting, 1919

Nicholson and Rohrbach's Cost Accounting is a revision and extension of Nicholson's "Cost Accounting, Theory and Practice," published in 1913, and represents a forward step in its particular field. There are seven distinct parts of the book, and the last preceding statement applies particularly to the first four parts, designated as follows:[11]

- Part I, Elements and Methods of Cost-Finding ;

- Part II, Factory Routine and Detailed Reports ;

- Part III, Compiling and Summarizing the Cost Records ;

- Part IV, Controlling the Cost Records.

The following three parts are:

- Part V, The Installation of a Cost System, is both descriptive and suggestive.

- Part VI, Simplified Cost Finding Methods, is again chiefly descriptive.

- Part VII, Cost-Pius Contracts, is analytical and suggestive, and contains that which will be regarded by many as the most valuable material in the volume. Chapters 31 and 32 contain the senior author's personal, not official, opinions concerning the correct accounting procedure in the handling of cost-plus contracts. In chapter 33, likewise, are found his personal opinions regarding the proper terms of cancellation of such contracts. These chapters are most timely and will be read with interest by professional accountants and contractors.[11]

General Functions of Cost Accounting

According to Nicholson (1920) it would be a mistake, to think that the scope of cost accounting is limited to finding costs only. The functions of a cost system are as follows:

Any good cost system, properly operated, performs two distinct, though related, functions.

- The first, which may be called the direct function, is that of ascertaining actual costs.

- The second, or indirect function, is that of supplying, in its system of reports, the information necessary to organize the many departments of a factory into working units, and to direct their activities in accord with some definite plan.[47]

About the relation of cost accounting and general accounting Nicholson (1920) proceeded:

Cost accounting, as a science, is a branch of general accounting. Its province is to analyze and record the cost of the various items of material, labor and indirect expense incurred in the operation of a factory, and to so compile these elements as to show the total production cost of a particular piece of work.[47]

And furthermore: "With the cost books once established, the best modem usage is to incorporate their record in total in the general financial books. In this way the modem cost system builds up an interlocking series of accounts which furnish the material for a detailed study of the operations of a manufacturing business."[47]

Elements and Methods of Cost-Finding

In his 1909 "Factory Organization and Costs" Nicholson already presented a first analyses regarding the relation of the cost elements to selling price, which was visualized in a diagram (see above). In his 1919 work he explained that this analyses can be part of a "uniform methods of cost-finding." This means outlining the standard principles of cost accounting and, from these principles, arriving at uniform methods of treating costs as applied to a particular industry.[48]

Nicholson explained that the greatest advantage to be derived from uniform cost methods is that of insuring a more uniform selling price. This object would be attained, even if the uniform system were not as scientific as it should be; for if errors were made through the method established, all manufacturers would at least be figuring the same way, all would be making the same mistakes, and unfair and ignorant competition would be eliminated.[48] Before determining the selling price of an article consideration must be given to the various elements of costs and expenses which have been classified as:[49]

- Direct material

- Direct labor

- Direct expenses

- Indirect charges

- Selling expenses

- Administrative expenses

The standard cost accounting system recognized not only expenses, but also different types of costs, and eventually the selling price:[49]

- Prime Cost. The sum of the direct material cost plus the direct labor cost is known as the prime cost.

- Factory Cost. The sum of the prime cost plus the indirect charges is known as the factory cost.

- Total Cost. The sum of the factory cost plus the selling expenses and the administrative expenses is known as the total cost.

- Selling Price. The sum of the total cost plus the profit is known as the selling price.

These gradations of cost may be further illustrated by means of the following simple diagram (diagram I), which illustrates the steps leading from the material cost to the selling price. This diagram is an extension of the analyses of cost accounting, Nicholson presented in 1909.[50] This type of visual analytics was presented earlier by Church (1901),[51] and became more common in introductory textbooks; see for example Webner (1911),[52] Kimball (1914),[53] Larson (1916),[54] and Newlove (1923).[55]

- Elements and Methods of Cost-Finding

I : Relations of Cost Elements to Selling Price

I : Relations of Cost Elements to Selling Price II: Analysis of Cost Elements

II: Analysis of Cost Elements

Nicholson continued, that in practice it is customary to allow certain deductions from the established selling prices, or from the established purchasing prices. These deductions can include trade discounts, allowances, rebates and/or cash discount.[49] As to the analysis of total of cost elements, every cost element can be traced back to certain kind of expenses, see diagram II. This kind of diagram was also more common in those days; see for example Dana & Gillette (1909),[56] Kimball (1914),[57] Kimball (1917);[58] and Eggleston & Robinson (1921).[59]

Basic methods of cost-finding

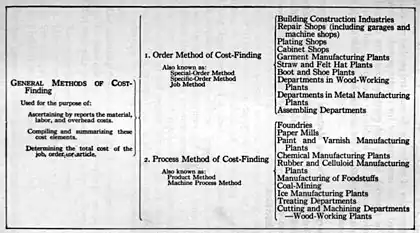

As costs furnish the basis for determining the selling prices of the manufactured product, they naturally should be compiled so that the total cost of the job, order, or article may be readily ascertained. Actual conditions in manufacturing determine the system of cost-finding to be used, which should include :[60]

- A method of ascertaining or reporting the material, labor, and overhead costs.

- A method of compiling these elements of cost.

- A method of determining the total cost of the job, order, or article.

For present purposes the actual conditions which exist in manufacturing industries may be grouped or summarized in two general classes, and the methods of cost-finding applicable to these two classes may be designated as follows:[60]

- Order method of cost-finding : When the order is the tangible basis upon which the elements of cost are charged, compiled, and determined, the order method of cost-finding is generally used. In other words, under such conditions the material costs, labor costs, and a pro rata share of the factory overhead are all charged to definite factory orders, and the elements of material, labor, and overhead costs are compiled so that the total factory cost of each individual order may be determined. If a number of units are manufactured under the definite factory order, the unit article cost may be determined by dividing the total factory cost by the total quantity manufactured or produced. Definite factory orders may be issued for the manufacture of a number of units, for a single unit, or for the manufacture of certain parts of a unit.[60]

- Process method of cost-finding : Whenever the process of manufacture is continuous for regular periods of time so that the definite factory orders and jobs lose their identity and become part of a large volume of production, the material, labor, and overhead costs are chargeable to the definite processes or operations and the process method of cost-finding is used. This method is sometimes called the "product method of cost-finding." However, in view of the fact that the word *' product" refers more particularly to article rather than operation, the designation "process method of cost-finding" is more explicit and is preferable. This term includes the method commonly known as the "machine-cost method," for the reason that the same general principles of cost-finding apply.[60]

Form III shows in summarized form the two basic methods of cost-finding and the industries, or departments within a plant, to which they are applicable under the conditions already described.

Factory Routine and Detailed Reports

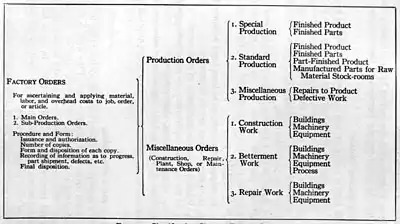

Before it can be decided which method of cost-finding may be used in any particular plant, the manufacturing departments of the plant must be classified. In some industries the order method of cost-finding might be applicable to certain departments, and the process method of cost-finding might be applicable to the remaining departments (see diagram IV).[61]

In designing the system of "Factory Routine and Detailed Reports" first a classification is presented of factory departments and of factory orders. Diagram 4 shows the classification of various factory departments in summarized form.[62]

- Classification Chart of Factory Departments and orders

IV: Classification Chart of Factory Departments

IV: Classification Chart of Factory Departments V: Classification Chart of Factory Orders, 1919

V: Classification Chart of Factory Orders, 1919

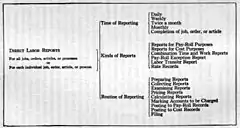

Diagram V summarizes the various kinds of factory orders which may be issued and the functions of these records.[63] Furthermore, the system of "Factory Routine and Detailed Reports," proposed by Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919), incorporates three types of reports about the handling of material, labor and production:

- System of Factory Routine and Detailed Reports

VI: Chart Showing Handling of Material and Material Reports

VI: Chart Showing Handling of Material and Material Reports VII: Classification Chart of Labor Reports

VII: Classification Chart of Labor Reports VIII: Classification Chart of Production Reports

VIII: Classification Chart of Production Reports

Diagram VI shows the various steps in the handling of material, and the material reports which are necessary to record material costs.[64] Diagram VII summarizes the various kinds of labor reports and the routine of reporting.[65] And diagram VIII summarizes the detailed items to be considered in the routine of production and the devising of production reports.[66]

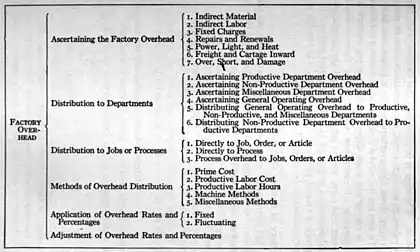

Distribution of Factory Overhead

At the turn of the 20th century, factory management was faced with the problem how overhead cost should be assigned to products, which lead to the modelling of costing systems. In the work of Nicholson the idea of cost centres was emphasizing, although he didn't coined or used the term itself. An accompanying problem was "how to distinguish between 'production' cost centres working directly for production and 'service provider' cost centres working for other centres... [to] cascade the distribution of the charges related to these cost centres."[67] According to Garner (1954) Nicholson in (1913) as well as to Webner (1917) and Taylor, where the first to tackle this problem.[67]

Nicholson and Rohrbach (1919) further summarized, that the factory overhead that cannot be absorbed in the article cost directly is applied indirectly in the following manner:[68]

- The elements of factory overhead cost are assigned equitably to specific departments of the factory, including productive, non-productive, and miscellaneous departments.

- The total cost of the indirect departments is then transferred to, and distributed over, the productive departments on some fair basis.

- The total amount of factory overhead expenses chargeable to each productive department is determined, and is then distributed over the various jobs, orders, articles, or processes.

Nicholson continued explaining about different methods of distributing overhead. Assuming the departmental method of distributing overhead has been adopted, he said, there still remains the most complex problem of all - upon what basis shall the overhead be distributed within the departments so that each job, order, or article may be charged with the portion that properly belongs to it? In those days five methods were more or less standard, applied under definite conditions of manufacture. These are:[68]

- Prime-cost method : the most simple method, which divides the total overhead expenses by the total material and labor costs, resulting in a decimal figure which is the rate to be used.

- Productive-labor-cost method : based upon the principle that indirect expenses are incurred in proportion to the cost of the labor involved. To operate the plan, the total amount of overhead expenses for a definite period is divided by the total cost of the direct labor for the same period.

- Productive-labor-hours method : similar as the productive-labor-cost method, but the amount of labor is measured by time and not by cost.

- Machine-rate methods : All machine-rate methods are based upon the principle that overhead expense accrues in proportion to the number of hours of machine operation.

- Miscellaneous methods : Various modifications and combinations of methods for the distribution of overhead have been devised to meet special conditions in different lines of business. For the most part they are "percentage" plans in some form or other.

The items which make up the factory overhead and the methods of distributing them first to departments and then to product are summarized in diagram IX.[68]

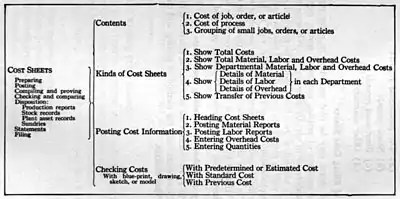

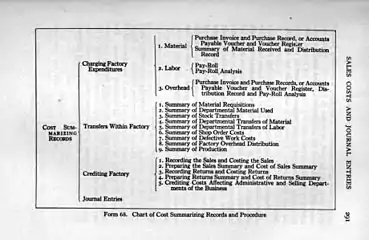

Compiling and Summarizing the Cost Records

Further classification of cost accounting details have been made as follows:

- Compiling and Summarizing the Cost Records

X: Classification Chart of Cost Sheets

X: Classification Chart of Cost Sheets XI. Chart of Cost Summarizing Records and Procedures

XI. Chart of Cost Summarizing Records and Procedures

Diagram X summarizes the information entered on different kinds of cost sheets and the method of posting and checking the data they contain,[69] and diagram XI shows in concrete form the cost summarizing records described all of Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919). The authors noted, that the distribution record, may be used for all summary purposes. The sheets of each summary may be classified in sections in a loose-leaf binder, each section being kept separate by means of tab indexes, thus providing a means for ready reference. The folios of each section should be numbered for posting purposes.[70]

Controlling the Cost Records

In the chapter about "General Ledger Control of Factory Accounts," Nicholson & Rohrbach explained that in large manufacturing concerns it is customary to provide a chart or a classified list of accounts showing the exact name of each and the transactions to be recorded therein. Where the classification is elaborate, it is well to use account numbers or symbols so as to facilitate ready reference to them and thus save the bookkeepers' time. The authors advise, that such a chart should be printed upon heavy paper or cardboard and hung in view of those who have occasion to refer to it frequently. Where desks are equipped with glass tops and the chart is inserted under the glass, reference can be made to it very readily.[71]

The requirements of each concern govern the number of copies of the chart of accounts to be prepared and the members of the staff to whom they are to be given. Ordinarily it is necessary for each clerk in the accounting and cost departments to have his own copy, while an additional copy should be given to the purchasing agent and treasurer or the officer who is in charge of the accounting records. Portions of the chart of accounts may be given to the plant superintendent, production manager, factory foreman, stock clerks, and factory clerks.[71]

The chart shown in diagram XII gives a classified list of accounts of a large manufacturing concern. Last part of the system presented are the scheme's concerning the controlling the cost records:[71]

- Elements and Methods of Cost-Finding

.jpg.webp) XII: Classification General Ledger Accounts (1)

XII: Classification General Ledger Accounts (1).jpg.webp) XII: Classification chart of General Ledger Accounts (2)

XII: Classification chart of General Ledger Accounts (2) XIII: Chart of Factory Ledger Controlling Accounts

XIII: Chart of Factory Ledger Controlling Accounts

Diagram XIII summarizes the discussion of the factory ledger accounts.[72] For the same reason that it is advantageous to draw up a classification sheet of the general ledger accounts of a large manufacturing plant, the factory ledger accounts may also be illustrated by means of a chart (diagram XIV). In preparing such a chart, the accounts should be given symbol numbers. It may be noted that factory ledger controlling accounts vary in number from the three simple accounts previously described to several hundred.[73]

- Classification chart of Factory Ledger Accounts

.jpg.webp) XIV: Classification chart of Factory Ledger Accounts (1)

XIV: Classification chart of Factory Ledger Accounts (1).jpg.webp) XIV: Classification chart of Factory Ledger Accounts (2)

XIV: Classification chart of Factory Ledger Accounts (2)

The arrangement of the accounts in the ledger should receive attention. While they are often arranged according to their symbol numbers, as their classification is more or less standardized according to Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919), they may be grouped in sections in the following order:

- Raw material accounts

- Work in process accounts

- Part-finished stock accounts

- Finished stock accounts

- Productive labor accounts

- Distributed overhead accounts

- Detailed factory overhead accounts

The sections should be distinguished by means of tab indexes marked according to the classifications. Where detailed overhead accounts are kept for each department, it may be well to furnish additional tab indexes within this section marked with the departments of the plant so that the overhead accounts of one department may be readily distinguished from those of another.[73] With these classification charts Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919) presented their idea's, which became known as the definition of cost centres.[67]

Reception

In a 1919 review in The American Economic Review, Stanley E. Howard stated, that the materials of the volume are well organized. The reader is given a bird's eye view of the problems dealt with, and is then shown in detail the development of cost and controlling records from the various business and factory forms. The authors have taken pains to emphasize relationships, presenting frequent summary charts. Fundamentals regarding the forms for orders, reports, and records have been illustrated, and the mistake has not been made of confounding multiplicity of illustration with clarity of exposition.[11]

The volume is intended for use by accountants, manufacturers, and students. Members of the first two groups, according to Howard (1919), would find particularly useful the information contained in the tables of approved depreciation rates for different types of assets, as well as the discussion of the relationship between Overtime and the modification of standard depreciation rates.[11]

Howard (1919) ended his review by stating, that the issue is probably beclouded by reason of the different points of view involved. The cost accountant wishes, among other things, to furnish the selling department adequate data upon which to base a price policy. The general accountant has in mind the preparation of correct, unpadded statements of condition and of operation. For the purposes of the one certain information is needed, which by the other should be discarded. Reconciliation of the opposing ideas ought to be possible, perhaps along the lines suggested by Messrs. Nicholson and Rohrbach.[11]

A second 1919 review by Arthur R. Burnet in the Publications of the American Statistical Association called the entire work a happy combination of theory and practical examples. Burnet found that the book is being used as a handbook in a number of organizations where cost systems were being installed or improved. The forms are illustrated and can be followed in actual practice. The chapter on the examination of the plant preparatory to the installation of a cost system, according to Burnet in those days, contained a valuable checking list which should furnish statisticians with a wealth of suggestions for the analysis of business.[74]

A 1920 review, in the Financial World, more in particular mentioned, that "in the methods of manufacture, greater care must be exercised. The functions of a cost system are well stated by Major J. Lee Nicholson..." in his 1919 work.[75]

Profitable Management, 1923

Nicholson last book was Profitable Management, published in 1923. A 1923 review in The Annalist commented:

The volume on "Profitable Management" by J. Lee Nicholson 's a bright star in the Ronald catalogue, and in its 117 pages it presents a vast array of worldly wisdom which should be taken to heart by men of business, great and small. For while the major part of Mr. Nicholson's counsels on the varied phases of commercial activity have reference to the more extensive industries, they are applicable to every kind of business which is called into existence for profit making...[76]

Hein (1959) further evaluated, that "modern writers on management theory and practice would have to examine it closely to find points not now being advocated in the current literature. It contains such recommendations as the costing of clerical and selling procedures, and the setting of standards as a means for comparison and control. Even today such procedures have not been widely adopted, although, since clerical costs are increasing at a faster rate than are factory costs, such control has much greater significance at the present time than it had in the early 1920s." [7]

Reception

Nicholson reputation as cost accounting pioneer was acknowledged in his days. A 1920 article in The Packages, mentioned that "Major J. Lee Nicholson... reputation as a cost accountant and author extends from one end of the country to the other..."[77] Nicholson is further remembered as founder of the National Association of Cost Accountants.[15][78]

In the Evolution of Cost Accounting to 1925 S. Paul Garner (1954) [79] described a number of important contributions by Nicholson. Hein (1959) summarized:

For instance, [Nicholson] proposed a summary of requisitions as an aid in posting to stores ledgers and cost records. In this same area of accounting for raw materials, Nicholson was an exponent of the use of a true perpetual inventory system. He did not originate this idea, but brought it to a high stage of perfection, designing raw materials ledger cards which had spaces not only for amounts and values, but also for items received and requisitioned, with the balance on hand indicated."[80]

Hein (1959) further summarized:

Garner credits Nicholson with the original development of the several methods of accounting for scrap (although some earlier pioneering work had been done in this area), and he feels that the works of subsequent writers are primarily elaborations of Nicholson's treatment. In the differentiation of the uses of, and the accounting for job order costing and process costing, Nicholson was especially farsighted, missing only the now-taken-for granted concept of equivalent production in the valuation of inventories and the calculation of the cost of goods sold. He was apparently the first individual to develop the concepts and comparative advantages of accounting for costs departmentally, on a cumulative or non-cumulative basis that is, pyramided and non-pyramided departmental costs.[30]

According to Chatfield (2014) Nicholson's later writings "anticipated post-1920 developments in the use of cost figures for decision making and in the psychology of cost control."[1] He explained:

[Nicholson's] experiences as head of a management consulting firm focused his attention on the relationship between cost accounting and industrial efficiency. He emphasized that cost accounting is a service function whose value depends on its usefulness to other departments. As a staff man negotiating with foremen and executives, the cost accountant must be diplomatic, yet forceful enough to take full advantage of the discipline that costing makes possible. Nicholson stressed the importance of supplying cost figures that are appropriate for each executive level, and the need to educate foremen and department heads about overhead costs as a first step toward controlling such costs. Cost accountants should give department managers comparative costs of materials, labor, overhead, production quantities, and inventories. Each production department should in turn inform the sales department how all these amounts are likely to vary in relation to changes in sales volume.[1]

And furthermore Nicholson "refined and disseminated new knowledge about cost accounting, which had recently undergone revolutionary changes... As one of the earliest American cost accountants to teach the subject at the university level, he helped standardize practice and facilitate the interaction of ideas between academics and practitioners."[1]

Selected publications

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee. Nicholson on Factory Organization and Costs. Kohl Technical Publishing Company, 1909; 2nd ed. 1911.

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee. Cost Accounting Theory and Practice, 1913.

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee, and John Francis Deems Rohrbach. Cost accounting. New York: Ronald Press, 1919. 2nd ed. 1920; 3rd ed. 1922.

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee. Standard basic course. Chicago, J. Lee Nicholson Institute of Cost Accounting, c. 1920–21.

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee. Profitable Management. Ronald Press Company, 1923.

- Stone, William M. et al. Accountants' and auditors' manual, by William M. Stone ... in collaboration with J. Lee Nicholson ... Charles J. Nasmyth ... and others .. Philadelphia, Pa. : David McKay company, 1925.

Articles, a selection:

- Nicholson, Jerome Lee (1949). "Variations in working-class family expenditure". Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General). 112 (4): 359–418. doi:10.2307/2980764. JSTOR 2980764.

References

- Chatfield (2014, p. 436)

- Taylor (1979, p. 7)

- The Congress (1930). International Congress on Accounting, 1929: September 9–14, 1929 ... New York City. [Proceedings], p. 1235.

- Hein (1959, p. 106)

- Mattessich, Richard (2003). "Accounting research and researchers of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century: an international survey of authors, ideas and publications" (PDF). Accounting, Business & Financial History. 13 (2): 143. doi:10.1080/0958520032000084978. S2CID 154487746.

- Richard Mattessich (2007) Two Hundred Years of Accounting Research. p. 176

- Hein (1959, p. 107)

- Nicholson (1913, p. i)

- National Association of Accountants (1921) Proceedings of the International Cost Conference. p. 45.

- The Accounting review. Vol. 34. (1959), p. 106.

- Stanley E. Howard. "Review of Cost Accounting. By J. Lee Nicholson and John F. D. Rohrbach. New York: The Ronald Press Company. 1919." in: The American Economic Review, Vol. 9, No. 3 (Sep., 1919), pp. 563-568.

- Michigan Manufacturer & Financial Record, Vol. 31. (1923). p. 10

- Vangermeersch, Richard (1995). "Review of "Proud of the Past: 75 Years of Excellence Through Leadership 1919-1994 by Grant U. Meyers, Erwin S. Koval". The Accounting Historians Journal. 22 (1): 169. JSTOR 40697626.

- Vangermeersch and Jordan (2014, p. 334-35)

- McLeod, S. C., "Major J. Lee Nicholson Dies Suddenly in San Francisco," N.A.C.A. Bulletin, November 15, 1924.

- Chandra, Gyan; Paperman, Jacob B. (1976). "Direct Costing Vs. Absorption Costing: A Historical Review". The Accounting Historians Journal. 3 (1/4): 1–9. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.3.1.1. JSTOR 40697404.

- The economist John Maurice Clark is known in the field of accountancy due to his famous Studies in the economics of overhead. (1909) Source: Mattessich (2007, p. 177)

- Nicholson and Rohrbach [1919, p. 1]; cited in: Boyns, Trevor, and John Richard Edwards. "British Cost and Management Accounting Theory and Practice, c. 1850—c. 1950; Resolved and Unresolved Issues." Business and Economic History (1997): 452-462.

- Nicholson (1909, p. iii)

- Lee Nicholson, J (1909). "Factory Organization and Costs: Book review". Journal of Accountancy. 8: 222.

- Nicholson (1909, 38-42)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 64)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 59)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 60-61)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 62)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 204)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 205-7)

- Nicholson (1909, 345-47)

- Quote cited in Taylor (1979) and Solomons (1994)

- Hein (1959, p. 109)

- Newlove, George Hillis (1975). "In all my years: Economic and legal causes of changes in accounting". The Accounting Historians Journal. 2 (1/4): 40–44. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.2.3.40. JSTOR 40697368.

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1913, p. 198)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1913, p. 214)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1913, p. 226)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1913, p. 236)

- George Hillis Newlove Cost accounts. 1922. p. 13-21

- Previts, Gary John (1974). "Old Wine and... The New Harvard Bottle". The Accounting Historians Journal. 1 (1/4): 19–20. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.1.3.19. JSTOR 40691037.

- J. Lee Nicholson. "Interest Should be Included as Part of the Cost," The Journal of Accountancy. Vol 15, mr. 2 (May 1913) p. 330-4

- William Andrew Paton and Russell Alger Stevenson in their Principles of Accounting (1919), p. 615; Cited in Stanley E. Howard (1919).

- Berk, Gerald (1997). "Discursive Cartels: Uniform Cost Accounting Among American Manufacturers Before the New Deal". Business and Economic History. 26 (1): 229–251. JSTOR 23703309.

- Nicholson cited in U.S. Federal Trade Commission, 1929. p. 12; Cited in Berk (1997).

- Okamoto, Kiyoshi (1966). "Evolution of Cost Accounting in the United States of America" (PDF). Hitotsubashi Journal of Commerce and Management. 4 (1): 32–58.

- Management Accounting, Vol. 25, Nr. 1 (1943), p. 393

- National Association of Cost Accountants (U.S.). Year book and proceedings of the ... International Cost Conference. New York : J. J. Little & Ives Co., 1920. p. 6-7

- Nicholson (1920, p. iii)

- Nicholson and Rohrbach (1919, p. iv) as cited in Burnet (1919)

- Nicholson (1920, p. 21)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 11-12)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 19-23)

- Nicholson (1909, p. 30)

- Church, Alexander Hamilton, "The Proper Distribution of Establishment Charges." in Engineering Magazine, July to Dec. 1901. p. 516

- Frank E. Webner. Factory costs, a work of reference for cost accountants and factory managers. 1911. p. 274

- Dexter S. Kimball. Auditing and cost-finding. Part I: Auditing, Part II: Cost-finding. New York, Alexander Hamilton institute, 1914. p. 241.

- Carl William Larson, Milk Production Cost Accounts, Principles and Methods. (1916), p. 3

- Newlove, George Hillis, Cost accounts, 1923. p. 7

- Gillette, Halbert Powers, and Richard T. Dana. Construction Cost Keeping and Management. Gillette Publishing Company, 1909. p. 129

- Dexter S. Kimball. Auditing and cost-finding. Part I: Auditing, Part II: Cost-finding. New York, Alexander Hamilton institute, 1914. p. 318.

- Dexter S. Kimball. Cost finding, 1917 p. 149

- De Witt Carl Eggleston & Frederick B. Robinson. Business costs. 1921. p. 23

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 25-34)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 35-57)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 40)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 55)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 95)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 121)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 209)

- Levant, Yves, and Henri Zimnovitch. "Equivalence methods: a little-known aspect of the history of costing." at researchgate.net. Accessed 2015-02-23.

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 163-182)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 230)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 292)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 310-314)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 330)

- Nicholson & Rohrbach (1919, p. 331-332)

- Arthur R. Burnet. "Reviewed Work: Cost Accounting by J. Lee Nicholson, John F. D. Rohrbach," in: Publications of the American Statistical Association, Vol. 16, No. 126 (Jun., 1919), pp. 405-406.

- Financial World, Vol 32, Part 2, (1919-20) p. 255

- The Annalist: A Magazine of Finance, Commerce and Economics, New York Times Company. Vol. 22 (1923) p. 705

- The Packages, Vol. 23. (1920). p. 17

- National Association of Cost Accountants (U.S.) . Official Publications. Vol. 7. (1964). p. 143

- Garner, S. Paul, Evolution of Cost Accounting to 1925, University, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 1954.

- Hein (1959, p. 108-9)

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from: Nicholson (1909) Factory Organization and Costs; L. G. (1909); Stanley E. Howard (1919) and some other PD sources listed.

This article incorporates public domain material from: Nicholson (1909) Factory Organization and Costs; L. G. (1909); Stanley E. Howard (1919) and some other PD sources listed.

Further reading

- Agami, Abdel M. Biographies of Notable Accountants. Random House, 1989.

- Chatfield, Michael. "Nicholson, J . Lee (1863-1924) ," in: History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia. Michael Chatfield, Richard Vangermeersch eds. 1996/2014. p. 436-7.

- Hein, Leonard W. (1959). "J. Lee Nicholson: pioneer cost accountant". Accounting Review. 34 (1): 106–111. JSTOR 241148.

- Scovell, Clinton H (1919). "Interest on Investment as a Factor in Manufacturing Costs". The American Economic Review. 1919 (1): 22–40. JSTOR 1813979.

- Solomons, David (1994). "Costing Pioneers: Some Links with the Past". The Accounting Historians Journal. 21 (2): 136. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.21.2.136.

- Taylor, Richard F. "Jerome Lee Nicholson" in: Accounting Historians Notebook, 1979, Vol. 2, no. 1 (spring), p. 7-9.

- Richard Vangermeersch and Robert Jordan, "Institute of Management Accountants," in: Michael Chatfield, Richard Vangermeersch (eds.), The History of Accounting (RLE Accounting): An International Encyclopedia 2014. p. 334-35.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jerome Lee Nicholson. |

- Jerome Lee Nicholson at clio.lib.olemiss.edu.