Järsberg Runestone

The Järsberg Runestone is a runestone in the elder futhark near Kristinehamn in Värmland, Sweden.

| Järsberg Runestone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Created | 6th century |

| Discovered | Järsberg, Kristinehamn, Värmland, Sweden |

| Rundata ID | Vr 1 |

| Runemaster | Unknown |

| Text – Native | |

| Proto-Norse :[Le]ubaz(?) haite. Hrabnaz hait[e]. Ek, erilaz, runoz writu. | |

| Translation | |

| Leubaz am I called. Hrafn am I called. I, the eril, write the runes. | |

Inscription

It contains the following runic text:

- ᚢᛒᚨᛉ ᚺᛁᛏᛖ ᛬ ᚺᚨᚱᚨᛒᚨᚾᚨᛉ ¶ ᚺᚨᛁᛏ ¶ ᛖᚲ ᛖᚱᛁᛚᚨᛉ ᚱᚢᚾᛟᛉ ᚹᚨᚱᛁᛏᚢ

The text as transliterated into Latin letters:

- ...ubaz hite ÷ h=arabana=z ¶ h=ait... ¶ ek e=rilaz runoz waritu[1]

As translated into English:

- Leubaz am I called. Hrafn am I called. I, the eril, write the runes.[1]

The name Hrabnaz or Hrafn translates as Raven.[2]

Interpretation

The Järsberg Runestone is a stone of reddish granite that is believed to have been part of a stone circle monument.[2] The upper part of the runestone is damaged; this was the case when the stone was found. It is thus impossible to say how much of the runic text has been lost. It is safe to assume that the right row is to be completed with an e, but the left row is more problematic. If the name is preserved, it was likely the man's name Ubaz (owl), but many assume that the name was Leubaz (pleasant), which is a name element known from another migration age runestone in Skärkind, Östergötland, that is designated as Ög 171. Moreover, the remainder of this row of runic text has not been positively interpreted either.

There are diverging opinions as to where the inscription starts.[3] This is because the upper part is lost and the fact that early runic inscriptions could be read from right to left. Usually the orientation of the runes indicate which direction, but the runes on this stone are ambiguous. In addition, the size of the last line of the text is smaller than the main section and "write the runes" is in a curved, serpentine fashion.[3]

Several runes could be united to form bind runes. In the Järsberg runestone, there are four such cases in the text, including both "h+a" combinations including that starting the name Hrafn.[3]

The last rune in the word runoz is upside-down. The Y-like rune in the word ek is a transitional form between the k-rune of the elder futhark and the younger futhark which is found on the Björketorp Runestone in Blekinge. Unlike the Björketorp runestone, there are no other runes that show transitional forms. The Järsberg runestone should consequently be older, thus it is dated to the early 6th century.

The word erilaz is known from several Proto-Norse inscriptions. The fact that it is a title, profession or something similar is certain, but not much more. There are many indications that it is connected to the title earl. According to a tradition from the 18th century, the older form of the name Järsberg was Jarlsberg ("Earl's hill"), and the monuments in the vicinity were remainders of the old earldom. However, medieval annotations of the name contradict that the name Järsberg is derived from jarl.

Site history

In Värmland, there are only four runestones of which two are from the Viking Age (in Old Norse) and the two others are from the Age of Migrations (in the older Proto-Norse). The Järsberg Runestone is one of the two earliest and it dates from the 6th century. It is raised along a trail called Letstigen which was a pre-historic trail going from the Swedish central region in the Mälaren basin to the central region of Vestfold in Norway.

The stone was discovered in 1862[4] and it was then lying on its side, partially covered by soil. It appeared to have the proper shape for a gate stone, but when runes were discovered on it, it was instead raised anew where it was found.

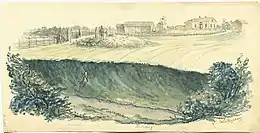

Those who formerly travelled the old trail met a more formidable sight than people do today. In the location there were eight more stones and there is a sketch from 1863 where both the stones and the location of the find are marked. Unfortunately both the raised stones and parts of the terrain where they were raised have disappeared due to agricultural work. Moreover, according to older information there was an additional stone circle at a small distance to the south of the field where the runestone is raised.

The disappeared monuments made many scholars convinced that the Järsberg runestone had been erected on a tumulus and several interpretations of the inscription have made this assumption.[4] In order to arrive at a secure conclusion, the Swedish National Heritage Board made an excavation in 1975, but no traces could be found of any graves.[4] Furthermore, no archaeological finds were made. The excavation concluded that the burrow was a natural feature.[4]

However, in connection with the revision of pre-historic monuments which was made in 1987, a glass bead was found near the runestone. This kind of find indicates a woman's grave. An archaeologist has maintained that the profile of the hill that was made during the excavation in 1975 gave the impression of a large tumulus. However, there is at the moment no consensus as to whether there was a tumulus or not.

In fiction

The Swedish author Jan Andersson has written a novel Jag, Herulen: En värmländsk historia about the making of the stone. The book is based on the theory that Erilaz refers to the Heruli, a Germanic tribe which Procopius reported had returned to Scandinavia. In the book, the returning Heruls pass through Geatish territory and find a mostly unsettled land which becomes Värmland.

References

- Projektet Samnordisk runtextdatabas Archived 2011-08-11 at WebCite - Rundata

- Looijenga (2003:331).

- Antonsen (2002:120-123).

- Jansson (1976:89-95).

Sources

- Antonsen, Elmer H. (2002). Runes and Germanic Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017462-6.

- Jansson, Sven B. F. (1976). "Angående Järsbergsstenen" (PDF). Fornvännen. Swedish National Heritage Board. 71: 89–95. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- Looijenga, Tineke (2003). Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12396-2.

- Järsberg, an article at the Swedish National Heritage Board, retrieved May 14, 2007.

- Rundata