Isaac de Pinto

Isaac de Pinto (Amsterdam, 10 April 1717 – 13 August 1787 in the Hague) was a Dutch Jew of Portuguese origin, a merchant/banker, one of the main investors in the Dutch East India Company, a scholar, and a philosophe who concentrated on Jewish emancipation and National Debt. "He was one of the very few Jews of the eighteenth century, before Moses Mendelssohn, able to operate and express himself in the mainstreams of European culture."[1]

Life

Isaac had his Brit milah on 18 April 1717; this likely means he was born on 10 April and received his Bar Mitzvah in 1730. The 17-year old Pinto married on 29 December 1734 to Rachel Nuñes Henriques; the couple never had any children. In 1748 Pinto helped stadholder prince William IV of Orange, sending or lending him money to defeat the French at Bergen op Zoom. In return he asked for uplifting measures against Jewish merchants forbidding them to sell clothes, gherkins or fish on the street. He proposed to open the guilds for the Jews and to send the poorest to Surinam. In 1750 he was appointed by the prince as the president of the Dutch East India Company.

Pinto was a man of broad learning, but did not begin to write until nearly forty-five, when he acquired a reputation by defending his co-religionists against Voltaire. In 1762 he published his Essai sur le Luxe at Amsterdam. In the same year appeared his Apologie pour la Nation Juive, ou Réflexions Critiques. The author sent a manuscript copy of this work to Voltaire. Antoine Guenée reproduced the Apologie at the head of his Lettres de Quelques Juifs Portugais, Allemands et Polonais, à M. de Voltaire.

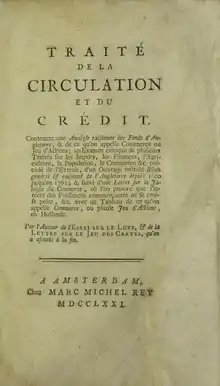

In 1761 De Pinto and his brother Aron went bankrupt maybe as a result of raising loans of 6 or 6.6 million guilders for the British government, in either 1759[2][3] or 1761;[4] his brother sold his house on Nieuwe Herengracht. De Pinto moved to Paris, where he met with James Cockburn, Lord Hertford, Mattheus Lestevenon, David Hume[5] John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford[6] and Denis Diderot. Then he moved to The Hague and lived in a mansion at Lange Voorhout; he and his family were invited to the palace when Mozart and his sister played. In 1767 he went to London, met with Lord Bute where he received a pension for his advice on the Treaty of Paris (1763), as the British gained influence over the French in India through his suggestion. "He pointed out that if the British did not obtain this change, war would probably break out again."[7] In 1768, Pinto sent a letter to Diderot on Du Jeu de Cartes. His Traité de la Circulation et du Crédit in which "he convinced many people that England was not on the verge of bankruptcy",[8] started in 1761, appeared in Amsterdam in 1771. He disagreed with Hume, Vivant de Mezague and Mirabeau. His treatise was twice reprinted, besides being translated into English by Philip Francis (politician)[9] and into German by Carl August von Struensee. His Précis des Arguments Contre les Matérialistes was published at The Hague in 1774. Pinto published mainly in French and once in Portuguese. He seems also to have Jean-Paul Marat, whom he pushed from the stairs and ordered to leave his house.[10] In 1776 he wrote against the American revolutionaries; he did approve the Boston Tea Party. Around 1780 he disapproved an alliance of the Dutch Republic with France.

Legacy

Various authors, both contemporary and later, commented on Pinto's writings. One of them, Karl Marx, derisively referred to Pinto - whom he regarded as a major exponent of the free-market liberalism he criticized - as the "Pindar of the Amsterdam stock exchange" for his glorification of the Dutch financial system.

References

- POPKIN, R. H. (1970). Hume and Isaac de Pinto. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 12(3), p. 430.

- J.S. Wijler (1923) Isaac de Pinto, Sa vie et ses oeuvres, p. 108

- Hume's Political Economy edited by Margaret Schabas & Carl Wennerlind

- Jews and Modern Jewish Identity: Rethinking the Enlightenment by Harvey Mitchell

- Hume: An Intellectual Biography by James A. Harris

- POPKIN, R. H. (1970). Hume and Isaac de Pinto. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 12(3), 417–430. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40754109

- POPKIN, R. H. (1970). Hume and Isaac de Pinto. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 12(3), p. 422.

- POPKIN, R. H. (1970). Hume and Isaac de Pinto. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 12(3), 420.

- An essay on circulation and credit: in four parts; and a letter on the jealousy of commerce. From the French of Monsieur de Pinto. Translated, with annotations, by the Rev. S. Baggs, M.A. Traité de la circulation et du crédit. English (http://ota.ox.ac.uk/id/5030) by Pinto, Isaac de, 1715-1787., licensed as Creative Commons BY-NC-SA (2.0 UK).

- J.S. Wijler (1923) Isaac de Pinto, Sa vie et ses oeuvres, p. 20

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Pinto". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Pinto". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Didot, Nouvelle Biographie Générale, p. 282;

- Barbier, Dictionnaire des Anonymes;

- Dictionnaire d'Economie Politicale, ii.;

- Quérard, La France Littéraire, in Allgemeine Litteraturzeitung, 1787, No. 273.

- Nijenhuis, I.J.A.(1992) Een joodse "philosophe". Isaac de Pinto (1717-1787) en de ontwikkeling van de politieke economie in de Europese Verlichting.