Irrigation in Vietnam

Although it is a country of high annual rainfall, irrigation in Vietnam is widespread. The reason is the uneven distribution of rainwater in space and in time. Irrigation management is mainly dominated by the state whereas there have been certain reforms leading to change during the last years. Awareness rising concerning environmental issues is starting to reach the people in Vietnam as well. Different strategies have been developed within the last decade to deal with environmental problems and mitigate possible impacts of climate change. With the implementation of different management structures taking into account the people's local needs, Vietnam is starting to follow Integrated Water Resources Management principles.

History of the irrigation sector

| Irrigation in Vietnam | |

|---|---|

| Land area | 330,000 km2 |

| Agricultural land | 94,096 km2 (28.51%) |

| Cultivated area equipped for irrigation | 25.27% |

| Irrigated area | 83,400 km2 |

| Water sources for irrigation | Surface water, Groundwater |

| Tariff | Irrigation Service Fees (ISF) dependent on crop type and irrigation pattern; since 2008 abolished |

Agricultural land under irrigation; past and present trends

Vietnam is one of the largest rice exporter since the late 1980s and early 1990s. Previous to the Doi Moi reforms initiated in 1986, the country was dependent on net imports of rice. After having changed the policies and opened the market, Vietnam was finally able to earn foreign exchange within these years and hence gain financial power. The domestic economy grew rapidly. Nowadays, irrigated agriculture is by far the largest water user and although the country is developing very fast, agriculture which is predicted to grow moderately remains to be an important employer in Vietnam.[1]

Irrigation infrastructure

Due to the shift of agriculture from self-supporting production to highly intensified cropland systems there has been a total investment of the Vietnamese Government of ~125 trillion VND in irrigation infrastructure during the last four decades. The constructions built during that time include approximately 100 large to medium scale hydraulic works. Furthermore, there are more than 8000 other irrigation systems (e.g. reservoirs, weirs, irrigation and drainage gates and pumping stations). The main irrigation form used is paddy field irrigation.[1] Whereas gravity irrigation is widely distributed in the Mekong region, in the Central North and coastal regions (3/5 of total irrigation schemes). Irrigation utilizing pumps (electric or with oil engines) is mainly located in the delta regions (~2/3 of total). The other irrigation forms are informal (non-governmental) systems like small private pumps or small gravity diversions.[2] Other investments are made by foreign donors; both foreign and internal investments tend to concentrate on the upgrading and rehabilitation of irrigation and drainage schemes.[3]

External Investment Proposals 1995-2000

| Project | Investment (in US $ Millions) |

|---|---|

| Red River Irrigation & Development | 95 |

| Central Region Irrigation Rehabilitation and Completion | 86 |

| Tan Chi Pumping Station, Ha Bac Province | 10 |

| Bac Vam Nao System, An Giang Province | 9 |

| Trang Vinh Irrigation System, Quang Ninh Province | 13 |

| southern Mang Thit Irrigation Scheme, Mekong Delta | 108 |

| Secondary Channels, Mekong Delta | 99 |

| Quang Le Phug Hiep Irrigation Scheme | 40 |

| Northern Province Sea Levee Rehabilitation and Upgrading | 26 |

| Nam Rom Irrigation Rehabilitation | 4 |

| Go Mieu Irrigation Rehabilitation | 6 |

| Bao Dai Irrigation Project | 3 |

| song Hinh | 18 |

| Truoi Reservoir, North of Huong River | 15 |

| Van Phong Irrigation System | 10 |

| Upper Ya Soup Irrigation | 14 |

| Cam Rang | 12 |

| Nha Trang | 10 |

| Ca Day Irrigation System | 7 |

| Tan Giang Irrigation System | 7 |

| Phuc Hoa System | 114 |

| Ca Giay Reservoir | 12 |

| Cau Moi Irrigation Project | 7 |

| Total | 725 |

Source: World Bank et al, Viet Nam Water Resources Sector Review 1996[3]

Institutional development

As irrigation in Vietnam is an essential component for the farmers to achieve middle income status, its development is based on institutional reforms and settings. The Vietnamese government still has the major institutional predominance. Nevertheless, in the beginning of the 21st century the policy of irrigation management transfer led to the establishment of water user associations (WUAs) and the development of participatory irrigation management (PIM). In the process of decentralization, the WUAs gain responsibilities for commune and inter-commune branch canals and structures while the PIM has been introduced in 15-20 provinces only supported by international donors. Irrigation service fees were collected until 2008 and abolished afterwards dispossessing a high amount of the financial basis for the local Irrigation and Drainage Management Companies (IDMCs) and WUAs.[1]

Environmental aspects

Linkages with water resources

Vietnam counts as one of the highest rainfall countries in the world with an annual precipitation of 1940 mm making a total volume of 640 billion m3 per year. Although the amount of water is comparably high, the distribution is uneven in time and in space. The rainy season lasts 4–5 months and during this time 75-85% of the total volume of precipitation occurs.

The water availability in Vietnam is supposed to be 830-840 billion m3 annually from which approximately 37% is generated on Vietnamese territory. More than 2,000 rivers (with a length >10 km) and more than 100 main rivers belong to Vietnam. 13 of these rivers have a basin area of more than 10,000 km2 with 10 being international ones. Nine rivers count as major ones accounting for ~93% of the total basin area; these are the Red River, Thái Bình River, Bằng Giang-Kỳ Cùng rivers, Ma River, Cả River, Vu Gia-Thu Bồn rivers, Đà Rằng River, Đồng Nai River and Cửu Long River. Beneath an uncountable number of lakes, ponds, lagoons and pools, there are water reservoirs with a total capacity of 26 billion cubic metres (21,000,000 acre feet). The main purpose of the reservoirs is to generate hydropower. Six of them have a capacity of more than 1 billion cubic metres (810,000 acre feet); Thác Bà (2.94 billion cubic metres (2,380,000 acre feet)), Hòa Bình (9.45 billion cubic metres (7,660,000 acre feet)), Trị An (2.76 billion cubic metres (2,240,000 acre feet)), Thác Mơ (1.31 billion cubic metres (1,060,000 acre feet)), Yaly (1.04 billion cubic metres (840,000 acre feet)) and Dau Tieng (1.45 billion cubic metres (1,180,000 acre feet)). Water reservoirs for irrigation in general have a capacity <10 million m3. Groundwater resources include yielding aquifers mainly located in the North and South of Vietnam. However, ground water is not yet well exploited. The following figure shows how the uneven distribution of water leads to water shortages both regionally and seasonally. Both indicators (annual water availability and dry season water availability indicator show the discharge of the river basin divided by the population of this basin).[1]

Environmental impacts of irrigation

The environmental impacts of irrigation in Vietnam are mainly:

1. Pollution of water resources caused by the overuse of pesticides and chemical fertilizers. In many cases, these kinds of pollution results from rural production which is small scaled but highly dense. The farmers are not aware of the health and environmental risks they cause by using too much pesticide. They tend to use a 2 to 4 times higher dosage than recommended. They are not equipped with high quality spraying equipment and a survey showed that the products of high toxicity were freely available on the Vietnamese market. Fertilizers are often used unnecessarily or to an extremely high extent.[1]

2. High amount of water losses due to insufficient irrigation systems and structures which lack maintenance and operate ineffectively. Some irrigation schemes have a development factor of only 44% (indicating the development of the scheme compared with its designed potential) .[1]

3. Saline intrusion and degradation of soils. Although there has not been sufficient research yet, saline intrusion and the degradation of soils due to erosion or chemical deterioration cause serious problems locally.[5]

Legal and institutional framework

Legal framework

According to the Vietnamese Legislation, the entire population owns the water resources and single users and organizations are legally allowed to use them in order to meet their daily life and production. Apart from that, they are obligated to take care of a responsible water use and are supposed to protect all water resources. Nevertheless, the management of water resources is uniformly organized by the state. The legal framework concerning the management of water resources in general and the irrigation framework in particular is quite complicated in structure. Mainly, there are two documents providing rules and regulations for the use of water resources for irrigation. These are the Law on Water Resources (from the year 1998) and the Law on Land (replaced 1993). Especially for irrigation, there is the ordinance for the Exploitation and Protection of Irrigation Works and there are different secondary regulations concerning water use and the protection of water resources. Besides, Vietnam has approved of and ratified different international conventions. The most important ones are the Ramsar convention (1989), the International Convention on Biodiversity (1993), the Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin (1195), the Basel Convention (1995), the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2002), the UN Framework on Climate Change (2002), the Kyoto Protocol on the Clean Development Mechanism (2002).[6]

Institutional framework

The institutional framework can be divided into three main categories: The national (see table=central), provincial (see table= Province) and local level (see table=Districts, communes, etc.): Irrigation on national scale is primarily managed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD). The provincial counterparts to MARD are the DARDs (Departments of Agriculture and Rural Development). On the local level, there are Irrigation and Drainage Management Companies (IDMCs) as well as Water Users Associations (WUS) and some Participatory Irrigation Management (PIM) institutions (which are not based on legal policies actually but exist due to the MARD Minister's decision).

Their responsibilities are the following:

MARD: Major irrigation infrastructure and development is organized by the MARD Department of Water Resources and associated institutes. Furthermore, there are 12 corporations and 317 companies controlled by the MARD.

DARDs: They are responsible for supporting irrigation infrastructure in a smaller scale and assist in both, technical aspects and planning of irrigation and drainage schemes.

IDMCs: They manage the headworks and main canals as well as pumping stations, sluices to take out water from main, primary and secondary canals.

WUAs: They negotiate with IDMCs about water supply agreements and are responsible for the operation and maintenance of pumping stations and other off-taking water structures applied to serve only one commune, company or individual farms.

PIMs: Operation differs according to the circumstances of the area they are implemented in. Small scale structures are managed by the commune or the cooperatives themselves. These include structures that irrigate or drain areas within one commune.[6]

Irrigation Management in Vietnam

| Level | Level | Technical Agency | Irrigation Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Government | MARD | -- |

| Province | Provincial People's Committee | PARD | Irrigation&Drainage Management Company |

| District | District People's Committee | DARD | Irrigation Enterprise; Irrigation (Sub)Station |

| Commune | Commune People's Committee | -- | Cooperative Irrigation Team |

| Village | Village Head | -- | Cooperative Irrigation Team |

| Hamlet | Hamlet Head | -- | Farmers |

Source: Biltonen et al, Pro-poor Intervention Strategies in Irrigated Agriculture in Asia (2003)[2]

Current trends regarding policies

The Vietnamese government is following a policy of decentralization concerning irrigation management with announcements on irrigation and management transfer (IMT, in the year 2001) and different guidelines concerning the WUAs and PIMs. Basically these regulations say that main infrastructure and complex systems will remain under the responsibilities of IDMCs. At the same time, WUAs shall gain the responsibilities for commune and inter-communes structure.[6] The National Water Resources Strategy towards the Year 2020, set up by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE), recommends a uniform way of water management in all fields based on a river-basin approach. Especially for the irrigation sector they advise a shift in policies from supply-focused to demand-focused approach which might reflect the nature of water service products more effectively. Furthermore, they recommend the (re)implementation of fees, duties and tax policies. These are supposed to reflect the real costs of a water unit in order to ensure the security and sustainability of water services.[7]

Economic aspects

Water fees

Until 2008 there were Irrigation Service Fees (ISF) collected which were mainly based on crop type, cropping season, output and way of irrigation (partial, full). For disadvantaged farmers it was possible to avoid paying fees (e.g. when the yield was destroyed by natural disasters). In the year 2006 935.3 billion VND could be collected, 68% of that money covered approximately 40% of the IDMCs running costs (the other 32% of the fees were collected for the WUAs).[1]

Investment

The central and local governments as well as foreign donors generally invest capital in irrigation and drainage (see Fig. 3 for details). Data on provincial investment for the years 2001-2005 are not available. International donors mainly invested in local projects or supported the government with loans.[1]

Economic importance of irrigated areas

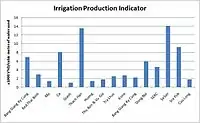

Due to the fast development of service and industry sectors in Vietnam during the last decades the contribution of agriculture to the national GDP decreases continuously from 80 to 90% to approximately 30-50%. Nevertheless, agriculture remains to be an important sector providing employment especially in the rural areas. Furthermore, the contribution of irrigated agriculture does not include fisheries, aquaculture, forestry or rain-fed agriculture so does not reflect the agricultural sector as a whole. The economic returns from irrigation production activities for each unit of water used vary significantly dependent on river basin (from 1,000 VND/m3 to 14,000 VND/m3). It can be assumed that the lower the return, the lower the level of efficiency or the lower the value of the irrigated crop.[1]

Possible effects of climate change on irrigation

Current predictions based on the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report 2007 say that Climate Change might impact the countries closer to the equator more seriously than the countries located more in the North or South. Tropical Vietnam is assumed to be one of the most vulnerable countries in connection with Climate Change. The medium emission level scenario for 2080-2099 predicts a higher annual rainfall which occurs in the already wet months of the year. At the same time, the dry months might become even hotter due to temperature rise and the stress on the crops might increase due to higher evaporation rates and less available water. Like the current climate differs both in time and in space, also the changing climate is predicted to affect rather the North than the South and it might influence rather the winter than the summer months. Beneath rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns, sea level rise is predicted to affect Vietnam as a country with a coastal line of more than 3,000 km especially. The loss of land and soils due to flooding and inundation might lead to a loss of 5% of the total land seriously affecting agriculture, industry, human and natural environment. Salt water intrusion and salinisation of soils and irrigation water (either groundwater or surface water of other water bodies) are predicted to cause serious problems in connection with sea level rise as well.[1]

Lessons learned from Vietnam's irrigation model

As Vietnam has to cope with many changes due to its fast development, the water sector in general and the irrigation sector in particular face great challenges. The current status leaves great potential to improve the system towards a sustainable irrigation management. Nevertheless, the participation in international conferences and the trend of the government to decentralize the system and implement a participatory based irrigation management strategy suggest that this country is willing to develop its policies further in order to gain long-term food security and save its natural resources at the same time.

See also

References

- Kellog Brown & Root Pty Ltd (2008). "Vietnam Water Sector Review Project. Status Report" (PDF). pp. 1–190. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Biltonen, Eric; Hussain, Intizar; Tuan, Doan Doan, eds. (2003). "Vietnam Country Report: Pro-poor Intervention Strategies in Irrigated Agriculture in Asia". International Water Management Institute. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Viet Nam Water Resources Sector Review" (PDF). World Bank. 1996. pp. 61–64. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Kellog Brown & Root Pty Ltd. "Vietnam Water Sector Review Project. StatusReport.Appendix" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - van Lynden, G.W.J.; Oldeman, L.R. (February 1997). "The Assessment of the Status of Human-Induced Soil Degradation in South and Southeast Asia" (PDF). International Soil Reference and Information Centre (ISRIC). pp. 1–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-03-06. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Nguyen, Thi Phuong Loan (2010). "Legal Framework of the Water Sector in Vietnam ZEF Working Paper Series 52" (PDF). Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung. pp. 1–111. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - n.n. (2006). "National Water Resources Strategy Towards the Year 2020" (PDF). Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE). pp. 1–32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17. Retrieved December 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)