International Networking Working Group

The International Networking Working Group (INWG) was a group of prominent computer science researchers in the 1970s who studied and developed standards and protocols for computer networking. Set up in 1972 as an informal group to consider the technical issues involved in connecting different networks, it became a subcommittee of the International Federation for Information Processing later that year. Ideas developed by members of the group contributed to the original "Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication" proposed by Bob Kahn and Vint Cerf in 1974.

History

The International Networking Working Group formed in October 1972 at the International Conference on Computer Communication held in Washington D.C. Its purpose was to study and develop communication protocols and standards for internetworking. The group was modelled on the ARPANET "Networking Working Group" created by Steve Crocker.[1]

Vint Cerf led the INWG and other active members included Alex McKenzie, Donald Davies, Roger Scantlebury, Louis Pouzin and Hubert Zimmermann.[2][3][4] These researchers represented the American ARPANET,[nb 1] the French CYCLADES project, and the British team working on the NPL network and subsequently the European Informatics Network.[2] Pouzin arranged affiliation with the International Federation for Information Processing (IFIP), and INWG became IFIP working group 1 under Technical Committee 6 (Data Communication) with the title "International Packet Switching for Computer Sharing". This standing, although informal, enabled the group to provide technical input on packet networking to CCITT and ISO.[2][4][5][6]

Louis Pouzin introduced the term catenet, the original term for an interconnected network, in October 1973,[2] published in a 1974 paper "A Proposal for Interconnecting Packet Switching Networks".[7]

Bob Kahn (who was not a member of INWG) and Vint Cerf acknowledged several members of the group in their 1974 paper "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication", which introduced the term internet as a shorthand for internetwork.[8][9]

Over three years, the group shared numerous numbered 'notes'. There were two competing proposals, INWG 37 based on the early Transmission Control Program proposed by Khan and Cerf, and INWG 61 based on CYCLADES TS proposed by Pouzin and Zimmermann. There were two sticking points (how fragmentation should work; and whether the data flow was an undifferentiated stream or maintained the integrity of the units sent). These were not major differences and after "hot debate" a synthesis was proposed in INWG 96.[2][10]

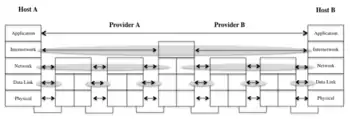

This protocol, agreed by the group in 1975, titled "Proposal for an international end to end protocol", was written by Vint Cerf, Alex McKenzie, Roger Scantlebury, and Hubert Zimmermann.[11] It was presented to the CCIT in 1976 by Derek Barber, who became INWG chair earlier that year. Although the protocol was adopted by networks in Europe,[12] it was not adopted by the CCIT or by the ARPANET. CCIT went on to adopt the X.25 standard in 1976, based on virtual circuits, and ARPA ultimately developed the Internet protocol suite, based on the Internet Protocol as connectionless layer and the Transmission Control Protocol as a reliable connection-oriented service.[2][3][5][13][14][15]

Later international work led to the OSI model in 1984, of which many members of the INWG became advocates.[3] For a period in the late 1980s and early 1990s, engineers, organizations and nations became polarized over the issue of which standard, the OSI model or the Internet protocol suite would result in the best and most robust computer networks.[3][16][17]

The INWG continued to work on protocol design and formal specification until the 1990s when it disbanded as the Internet grew rapidly.[2] Nonetheless, issues with the Internet Protocol suite remain and alternatives have been proposed building on INWG ideas such as Recursive Internetwork Architecture.[10]

Members

The group had about 100 members, including the following:[2][6]

- D. Barber

- B. Barker

- V. Cerf

- W. Clipsham

- D. Davies

- R. Despres

- V. Detwiler

- F. Heart

- A. McKenzie

- L. Pouzin

- O. Riml

- K. Samuelson

- K. Sandum

- R. Scantlebury

- B. Sexton

- P. Shanks

- C.D. Shepard

- J. Tucker

- B. Wessler

- H. Zimmerman

Notes

- Specifically, McKenzie represented BBN and Cerf represented Stanford University.

References

- "Internet founders say flexible framework was key to explosive growth". Princeton University. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- McKenzie, Alexander (2011). "INWG and the Conception of the Internet: An Eyewitness Account". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 33 (1): 66–71. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2011.9. ISSN 1934-1547.

- Andrew L. Russell (30 July 2013). "OSI: The Internet That Wasn't". IEEE Spectrum. Vol. 50 no. 8.

- Abbate, Janet (2000). Inventing the Internet. MIT Press. pp. 123–4. ISBN 978-0-262-51115-5.

- The "Hidden" Prehistory of European Research Networking. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-3935-6.

- Davies, Donald Watts (1979). Computer networks and their protocols. Internet Archive. Chichester, [Eng.] ; New York : Wiley. p. 466.

- A Proposal for Interconnecting Packet Switching Networks, L. Pouzin, Proceedings of EUROCOMP, Brunel University, May 1974, pp. 1023-36.

- Cerf, V.; Kahn, R. (1974). "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Communications. 22 (5): 637–648. doi:10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092259. ISSN 1558-0857.

The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations.

- "The internet's fifth man". Economist. 13 December 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

In the early 1970s Mr Pouzin created an innovative data network that linked locations in France, Italy and Britain. Its simplicity and efficiency pointed the way to a network that could connect not just dozens of machines, but millions of them. It captured the imagination of Dr Cerf and Dr Kahn, who included aspects of its design in the protocols that now power the internet.

- J. Day. How in the Heck Do You Lose a Layer!? 2nd IFIP International Conference of the Network of the Future, Paris, France, 2011

- Cerf, V.; McKenzie, A; Scantlebury, R; Zimmermann, H (1976). "Proposal for an international end to end protocol". ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. 6: 63–89. doi:10.1145/1015828.1015832.

- "Hubert Zimmerman". www.historyofcomputercommunications.info. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- Computer Networks and Their Protocols. Wiley. 1979. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-471-99750-4.

- Esmailzadeh, Riaz (2016-03-04). Broadband Telecommunications Technologies and Management. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-99565-5.

- Kerssens, Niels (2019-12-13). "Rethinking legacies in internet history: Euronet, lost (inter)networks, EU politics". Internet Histories. 0: 1–17. doi:10.1080/24701475.2019.1701919. ISSN 2470-1475.

- Russell, Andrew L. "Rough Consensus and Running Code' and the Internet-OSI Standards War" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing.

- Davies, Howard; Bressan, Beatrice (2010-04-26). A History of International Research Networking: The People who Made it Happen. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-3-527-32710-2.

Further reading

- Cerf, V.; McKenzie, A; Scantlebury, R; Zimmermann, H (1976). "Proposal for an international end to end protocol". ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review. 6: 63–89. doi:10.1145/1015828.1015832.