Intermediate value theorem

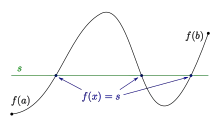

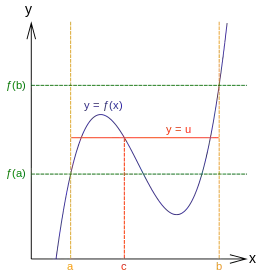

In mathematical analysis, the intermediate value theorem states that if f is a continuous function whose domain contains the interval [a, b], then it takes on any given value between f(a) and f(b) at some point within the interval.

This has two important corollaries:

Motivation

This captures an intuitive property of continuous functions over the real numbers: given f continuous on [1, 2] with the known values f(1) = 3 and f(2) = 5, then the graph of y = f(x) must pass through the horizontal line y = 4 while x moves from 1 to 2. It represents the idea that the graph of a continuous function on a closed interval can be drawn without lifting a pencil from the paper.

Theorem

The intermediate value theorem states the following:

Consider an interval of real numbers and a continuous function . Then

- Version I. if is a number between and ,

- that is, ,

- then there is a such that .

- Version II. the image set is also an interval, and it contains ,

Remark: Version II states that the set of function values has no gap. For any two function values , even if they are outside the interval between and , all points in the interval are also function values,

- .

A subset of the real numbers with no internal gap is an interval. Version I is naturally contained in Version II.

Relation to completeness

The theorem depends on, and is equivalent to, the completeness of the real numbers. The intermediate value theorem does not apply to the rational numbers ℚ because gaps exist between rational numbers; irrational numbers fill those gaps. For example, the function for satisfies and . However, there is no rational number such that , because is an irrational number.

Proof

The theorem may be proven as a consequence of the completeness property of the real numbers as follows:[2]

We shall prove the first case, . The second case is similar.

Let be the set of all such that . Then is non-empty since is an element of , and is bounded above by . Hence, by completeness, the supremum exists. That is, is the smallest number that is greater than or equal to every member of . We claim that .

Fix some . Since is continuous, there is a such that whenever . This means that

for all . By the properties of the supremum, there exists some that is contained in , and so

- .

Picking , we know that because is the supremum of . This means that

- .

Both inequalities

are valid for all , from which we deduce as the only possible value, as stated.

Remark: The intermediate value theorem can also be proved using the methods of non-standard analysis, which places "intuitive" arguments involving infinitesimals on a rigorous footing.[3]

History

For u = 0 above, the statement is also known as Bolzano's theorem. (Since there is nothing special about u = 0, this is obviously equivalent to the intermediate value theorem itself.) This theorem was first proved by Bernard Bolzano in 1817. Augustin-Louis Cauchy provided a proof in 1821.[4] Both were inspired by the goal of formalizing the analysis of functions and the work of Joseph-Louis Lagrange. The idea that continuous functions possess the intermediate value property has an earlier origin. Simon Stevin proved the intermediate value theorem for polynomials (using a cubic as an example) by providing an algorithm for constructing the decimal expansion of the solution. The algorithm iteratively subdivides the interval into 10 parts, producing an additional decimal digit at each step of the iteration.[5] Before the formal definition of continuity was given, the intermediate value property was given as part of the definition of a continuous function. Proponents include Louis Arbogast, who assumed the functions to have no jumps, satisfy the intermediate value property and have increments whose sizes corresponded to the sizes of the increments of the variable.[6] Earlier authors held the result to be intuitively obvious and requiring no proof. The insight of Bolzano and Cauchy was to define a general notion of continuity (in terms of infinitesimals in Cauchy's case and using real inequalities in Bolzano's case), and to provide a proof based on such definitions.

Generalizations

The intermediate value theorem is closely linked to the topological notion of connectedness and follows from the basic properties of connected sets in metric spaces and connected subsets of ℝ in particular:

- If and are metric spaces, is a continuous map, and is a connected subset, then is connected. (*)

- A subset is connected if and only if it satisfies the following property: . (**)

In fact, connectedness is a topological property and (*) generalizes to topological spaces: If and are topological spaces, is a continuous map, and is a connected space, then is connected. The preservation of connectedness under continuous maps can be thought of as a generalization of the intermediate value theorem, a property of real valued functions of a real variable, to continuous functions in general spaces.

Recall the first version of the intermediate value theorem, stated previously:

Intermediate value theorem. (Version I). Consider a closed interval in the real numbers and a continuous function . Then, if is a real number such that , there exists such that .

The intermediate value theorem is an immediate consequence of these two properties of connectedness:[7]

Proof: By (**), is a connected set. It follows from (*) that the image, , is also connected. For convenience, assume that . Then once more invoking (**), implies that , or for some . Since , must actually hold, and the desired conclusion follows. The same argument applies if , so we are done.

The intermediate value theorem generalizes in a natural way: Suppose that X is a connected topological space and (Y, <) is a totally ordered set equipped with the order topology, and let f : X → Y be a continuous map. If a and b are two points in X and u is a point in Y lying between f(a) and f(b) with respect to <, then there exists c in X such that f(c) = u. The original theorem is recovered by noting that ℝ is connected and that its natural topology is the order topology.

The Brouwer fixed-point theorem is a related theorem that, in one dimension, gives a special case of the intermediate value theorem.

Converse is false

A Darboux function is a real-valued function f that has the "intermediate value property," i.e., that satisfies the conclusion of the intermediate value theorem: for any two values a and b in the domain of f, and any y between f(a) and f(b), there is some c between a and b with f(c) = y. The intermediate value theorem says that every continuous function is a Darboux function. However, not every Darboux function is continuous; i.e., the converse of the intermediate value theorem is false.

As an example, take the function f : [0, ∞) → [−1, 1] defined by f(x) = sin(1/x) for x > 0 and f(0) = 0. This function is not continuous at x = 0 because the limit of f(x) as x tends to 0 does not exist; yet the function has the intermediate value property. Another, more complicated example is given by the Conway base 13 function.

In fact, Darboux's theorem states that all functions that result from the differentiation of some other function on some interval have the intermediate value property (even though they need not be continuous).

Historically, this intermediate value property has been suggested as a definition for continuity of real-valued functions;[8] this definition was not adopted.

Practical applications

A similar result is the Borsuk–Ulam theorem, which says that a continuous map from the -sphere to Euclidean -space will always map some pair of antipodal points to the same place.

Proof for 1-dimensional case: Take to be any continuous function on a circle. Draw a line through the center of the circle, intersecting it at two opposite points and . Define to be . If the line is rotated 180 degrees, the value −d will be obtained instead. Due to the intermediate value theorem there must be some intermediate rotation angle for which d = 0, and as a consequence f(A) = f(B) at this angle.

In general, for any continuous function whose domain is some closed convex -dimensional shape and any point inside the shape (not necessarily its center), there exist two antipodal points with respect to the given point whose functional value is the same.

The theorem also underpins the explanation of why rotating a wobbly table will bring it to stability (subject to certain easily met constraints).[9]

See also

References

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Bolzano's Theorem". MathWorld.

- Essentially follows Clarke, Douglas A. (1971). Foundations of Analysis. Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 284.

- Sanders, Sam (2017). "Nonstandard Analysis and Constructivism!". arXiv:1704.00281 [math.LO].

- Grabiner, Judith V. (March 1983). "Who Gave You the Epsilon? Cauchy and the Origins of Rigorous Calculus" (PDF). The American Mathematical Monthly. 90 (3): 185–194. doi:10.2307/2975545. JSTOR 2975545.

- Karin Usadi Katz and Mikhail G. Katz (2011) A Burgessian Critique of Nominalistic Tendencies in Contemporary Mathematics and its Historiography. Foundations of Science. doi:10.1007/s10699-011-9223-1 See link

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Intermediate value theorem", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 42, 93. ISBN 978-0-07-054235-8.

- Smorynski, Craig (2017-04-07). MVT: A Most Valuable Theorem. Springer. ISBN 9783319529561.

- Keith Devlin (2007) How to stabilize a wobbly table

External links

- Intermediate value theorem at ProofWiki

- Intermediate value Theorem - Bolzano Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Bolzano's Theorem by Julio Cesar de la Yncera, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Intermediate Value Theorem". MathWorld.

- Belk, Jim (January 2, 2012). "Two-dimensional version of the Intermediate Value Theorem". Stack Exchange.

- Mizar system proof: http://mizar.org/version/current/html/topreal5.html#T4