Indian cobra

The Indian cobra (Naja naja), also known as the spectacled cobra, Asian cobra, or binocellate cobra, is a species of the genus Naja found, in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Bhutan, and a member of the "big four" species that inflict the most snakebites on humans in India.[4][5] It is distinct from the king cobra which belongs to the monotypic genus Ophiophagus. The Indian cobra is revered in Indian mythology and culture, and is often seen with snake charmers. It is now protected in India under the Indian Wildlife Protection Act (1972).

| Indian cobra | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Elapidae |

| Genus: | Naja |

| Species: | N. naja |

| Binomial name | |

| Naja naja | |

| |

| Indian cobra distribution | |

| Synonyms[1][3] | |

| |

Taxonomy

The generic name and the specific epithet naja is a Latinisation of the Sanskrit word nāgá (नाग) meaning "cobra".[6]

The Indian cobra is classified under the genus Naja of the family Elapidae. The genus was first described by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768.[7] The species Naja naja was first described by the Swedish physician, zoologist, and botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1758.[2][8] The genus Naja was split into several subgenera based on various factors, including morphology, diet, and habitat. Naja naja is part of the subgenus Naja, along with all the other species of Asiatic cobras, including Naja kaouthia, Naja siamensis, Naja sputatrix, and the rest.

Naja naja is considered to be the prototypical cobra species within the subgenus Naja, and within the entire genus Naja. All Asiatic species of Naja were considered conspecific with Naja naja until the 1990s, often as subspecies thereof. Many of the subspecies were later found to be artificial or composites. This causes much potential confusion when interpreting older literature.[9]

The Indian cobra[10][11] or spectacled cobra,[4] being common in South Asia, is referred to by a number of local names deriving from the root of Nag (नाग) (Hindi, Marathi) (નાગ)(Gujarati), Moorkhan, മൂര്ഖന് (Malayalam), Naya-නයා or Nagaya-නාගයා (Sinhalese), నాగు పాము (Nagu Paamu) (Telugu),[11] ನಾಗರ ಹಾವು Nagara Haavu (Kannada),[11] Nalla pambu (நல்ல பாம்பு) (Tamil)[11] "Phetigom" (Assamese) and Gokhra (গোখরো) (Bengali)."ଗୋଖର ସାପ/ନାଗ ସାପ" in (Odia)

Description

.jpg.webp)

The Indian cobra is a moderately sized, heavy bodied species. This cobra species can easily be identified by its relatively large and quite impressive hood, which it expands when threatened.

Many specimens exhibit a hood mark. This hood mark is located at the rear of the Indian cobra's hood. When the hood mark is present, are two circular ocelli patterns connected by a curved line, evoking the image of spectacles.[12]

This species has a head which is elliptical, depressed, and very slightly distinct from the neck. The snout is short and rounded with large nostrils. The eyes are medium in size and the pupils are round.[13] The majority of adult specimens range from 1 to 1.5 metres (3.3 to 4.9 ft) in length. Some specimens, particularly those from Sri Lanka, may grow to lengths of 2.1 to 2.2 metres (6.9 to 7.2 ft), but this is relatively uncommon.[12]

The Indian cobra varies tremendously in colour and pattern throughout its range. The ventral scales or the underside colouration of this species can be grey, yellow, tan, brown, reddish or black. Dorsal scales of the Indian cobra may have a hood mark or colour patterns. The most common visible pattern is a posteriorly convex light band at the level of the 20th to 25th ventrals. Salt-and-pepper speckles, especially in adult specimens, are seen on the dorsal scales.

Specimens, particularly those found in Sri Lanka, may exhibit poorly defined banding on the dorsum. Ontogenetic colour change is frequently observed in specimens in the northwestern parts of their geographic range (southern Pakistan and northwestern India). In southern Pakistan, juvenile specimens may be grey in colour and may or may not have a hood mark. Adults on the other hand are typically uniformly black in colour on top (melanistic), while the underside, outside the throat region, is usually light.

Patterns on the throat and ventral scales are also variable in this species. The majority of specimens exhibit a light throat area followed by dark banding, which can be 4–7 ventral scales wide. Adult specimens also often exhibit a significant amount of mottling on the throat and on the venter, which makes patterns on this species less clear relative to patterns seen in other species of cobra. With the exception of specimens from the northwest, there is often a pair of lateral spots on the throat where the ventral and dorsal scales meet. The positioning of these spots varies, with northwestern specimens having the spots positioned more anterior, while specimens from elsewhere in their range are more posterior.

Scalation

Dorsal scales are smooth and strongly oblique. Midbody scales are in 23 rows (21–25), with 171–197 ventrals. There are 48–75 divided subcaudals and the anal shield is single. There are seven upper labials (3rd the largest and in contact with nasal anteriorly, 3rd and 4th in contact with eye) and 9-10 lower labials (small angular cuneate scale present between 4th and 5th lower labial), as well as one preocular in contact with internasals, and three postoculars. Temporals are 2 + 3.[13]

Similar species

The Oriental rat snake Ptyas mucosus is often mistaken for the Indian cobra; however, this snake is much longer and can easily be distinguished by the more prominent ridged appearance of its body. Other snakes that resemble Naja naja are the banded racer Argyrogena fasciolata and the Indian smooth snake Coronella brachyura.[4] Also, the monocled cobra (Naja kaouthia) may be confused with Naja naja; however, the monocled cobra has an "O"-shaped pattern on the back of the hood, while the Indian cobra has a spectacles-shaped pattern on its hood.

Distribution and habitat

The Indian cobra is native to the Indian subcontinent and can be found throughout India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and southern Nepal. In India, it may or may not occur in the state of Assam, some parts of Kashmir, and it does not occur in high altitudes of over 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) and in extreme desert regions. In Pakistan, it is absent in most of Balochistan province, parts of North-West Frontier Province, desert areas elsewhere and the Northern Areas. The most westerly record comes from Duki, Balochistan in Pakistan, while the most easterly record is from the Tangail District in Bangladesh. As this species has been observed in Drosh, in the Chitral Valley, it may also occur in the Kabul River Valley in extreme eastern Afghanistan.[12] There's been at least one report of this species occurring in Bhutan.[14]

The Indian cobra inhabits a wide range of habitats throughout its geographical range. It can be found in dense or open forests, plains, agricultural lands (rice paddy fields, wheat crops), rocky terrain, wetlands, and it can even be found in heavily populated urban areas, such as villages and city outskirts, ranging from sea level to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in altitude. This species is absent from true desert regions. The Indian cobra is often found in the vicinity of water. Preferred hiding locations are holes in embankments, tree hollows, termite mounds, rock piles and small mammal dens.[13][15]

Reproduction

Indian cobras are oviparous and lay their eggs between the months of April and July. The female snake usually lays between 10 and 30 eggs in rat holes or termite mounds and the eggs hatch 48 to 69 days later. The hatchlings measure between 20 and 30 centimetres (8 and 12 in) in length. The hatchlings are independent from birth and have fully functional venom glands.

Venom

The Indian cobra's venom mainly contains a powerful post-synaptic neurotoxin[13] and cardiotoxin.[13][16] The venom acts on the synaptic gaps of the nerves, thereby paralyzing muscles, and in severe bites leading to respiratory failure or cardiac arrest. The venom components include enzymes such as hyaluronidase that cause lysis and increase the spread of the venom. Envenomation symptoms may manifest between fifteen minutes and two hours following the bite.[17]

In mice, the SC LD50 range for this species is 0.45 mg/kg[18] – 0.75 mg/kg.[13][19] The average venom yield per bite is between 169 and 250 mg.[13] Though it is responsible for many bites, only a small percentage are fatal if proper medical treatment and anti-venom are given.[15] Mortality rate for untreated bite victims can vary from case to case, depending upon the quantity of venom delivered by the individual involved. According to one study, it is approximately 20–30%,[20] but in another study involving victims who were given prompt medical treatment, the mortality rate was only 9%. In Bangladesh it's responsible for most of the snake bite cases. [19]

The Indian cobra is one of the big four snakes of South Asia which are responsible for the majority of human deaths by snakebite in Asia. Polyvalent serum is available for treating snakebites caused by these species.[21] Zedoary, a local spice with a reputation for being effective against snakebite,[22] has shown promise in experiments testing its activity against cobra venom.[23]

The venom of young cobras has been used as a substance of abuse in India, with cases of snake charmers being paid for providing bites from their snakes. Though this practice is now seen as outdated, symptoms of such abuse include loss of consciousness, euphoria, and sedation.[24]

As of November 2016, an antivenom is currently being developed by the Costa Rican Clodomiro Picado Institute, and the clinical trial phase is in Sri Lanka.[25]

Genome

Previous cytogenetic analysis revealed the Indian cobra has a diploid karyotype of 38 chromosomes, compromising seven pairs of macro-chromosomes, 11 pairs of micro-chromosomes and one pair of sexual chromosomes.[26] Using next-generation sequencing and emerging genomic technologies, a de novo high-quality N. naja reference genome was published in 2020.[27] The estimated size of this haploid genome is of 1.79 Gb, which has 43.22% of repetitive content and 40.46% of GC content. Specifically, macro-chromosomes, which represent 88% of the genome, have 39.8% of GC content, while micro-chromosomes, that represent only 12% of the genome, contain 43.5% of GC content.[27]

Synteny analysis

Synteny analysis between the Indian cobra and the prairie rattlesnake genome revealed large syntenic blocks within macro, micro, and sexual chromosomes. This study allowed the observation of chromosomic fusion and fission events that are consistent with the difference in chromosome number between these species. For example, chromosome 4 of the Indian cobra shares syntenic regions with chromosomes 3 and 5 of the rattlesnake genome, indicating a possible fusion event. Besides, chromosomes 5 and 6 of the Indian cobra are syntenic to rattlesnake chromosome 4, indicating a possible fusion event between these chromosomes.[27]

On the other hand, by performing whole-genome synteny comparison between the Indian cobra and other reptilian and avian genomes, it was revealed the presence of large syntenic regions between macro, micro, and sexual chromosomes across species from these classes, which indicates changes in chromosome organization between reptile and avian genomes and is consistent with their evolutionary trajectories.[27]

Gene organization

Using protein homology information and expression data from different tissues of the cobra, 23,248 protein-coding genes, 31,447 transcripts, and 31,036 proteins, which included alternatively spliced products, where predicted from this genome. 85% of these predicted proteins contained start and stop codon, and 12% contained an N-terminal secretion signal sequence, which is an important feature in terms of toxins secretion from venom glands.[27]

Venom gland genes

Further studies on gene prediction and annotation of the Indian cobra genome identified 139 toxin genes from 33 protein families. These included families like three-finger toxins (3FTxs), snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMP), cysteine-rich secretory venom proteins and other toxins including natriuretic peptide, C-type lectin, snake venom serine proteinase (SVSP), Kunitz and venom complement-activating gene families, group I phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and one cobra venom factor (CVF) gene. These major toxin gene families in the Indian cobra are mostly found in the snake's macro-chromosomes, which differs from Crotalus virides (rattlesnake) that presents them in its micro-chromosomes, and is indicative of the differences in their venom evolution. Besides, comparison of venom gland genes between the Indian cobra and C. virides, identified 15 toxin gene families that are unique to the Indian cobra, which included cathelicidins and phospholipase B-like toxins.[27]

Venom gland transcriptome and toxin gene identification

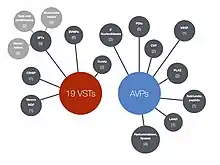

Analysis of transcriptomic data from 14 different tissues of the Indian cobra identified 19,426 expressed genes. Out of these genes, 12,346 belonged to the venom gland transcriptome, which included 139 genes from 33 toxin gene families. Additionally, differential expression analysis revealed that 109 genes from 15 different toxin gene families were significantly up-regulated (fold change > 2) in the venom gland and this included 19 genes that were exclusively expressed in this gland.[27]

These 19 venom specific toxins (VSTs) encode the core effector toxin proteins and include 9 three-finger toxins (out of which six are neurotoxins, one cytotoxin, one cardiotoxin and one muscarinic toxin), six snake venom metalloproteinases, one nerve growth factor, two venom Kunitz serine proteases and a cysteine-rich secretory venom protein.[27] Additionally to these VSTs, other accessory venom proteins (AVPs) were also found to be highly expressed in the venom gland such as: cobra venom factor (CVF), coagulation factors, protein disulfide isomerases, natriuretic peptides, hyaluronidases, phospholipases, L-amino acid oxidase (LAAO), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and 5' nucleotidases.[27]

This transcriptomic data together with the information provided by the high quality Indian cobra genome generated by Susyamohan et al., 2020 suggest that these VSTs together with AVPs form the core toxic effector components of this poisonous snake, which induce muscular paralysis, cardiovascular dysfunction, nausea, blurred vision and hemorrhage after snake bite.[27][28]

The identification of these genes coding for core toxic effector components from the Indian cobra venom may allow the development of recombinant antivenoms based in neutralizing antibodies for VST proteins.[27]

Popular culture

There are numerous myths about cobras in India, including the idea that they mate with rat snakes.[29]

Rudyard Kipling's short story "Rikki-Tikki-Tavi" features a pair of Indian cobras named Nag and Nagaina, the Hindi words for male and female snake, respectively.

Hinduism

The Indian cobra is greatly respected and feared, and even has its own place in Hindu mythology as a powerful deity. The Hindu god Shiva is often depicted with a cobra called Vasuki, coiled around his neck, symbolizing his mastery over "maya" or the world-illusion. Vishnu is usually portrayed as reclining on the coiled body of Adishesha, the Preeminent Serpent, a giant snake deity with multiple cobra heads. Cobras are also worshipped during the Hindu festival of Nag Panchami and Naagula Chavithi.

Snake charming

The Indian cobra's celebrity comes from its popularity as a Nipaie of choice for snake charmers. The cobra's dramatic threat posture makes for a unique spectacle, as it appears to sway to the tune of a snake charmer's flute. Snake charmers with their cobras in a wicker basket are a common sight in many parts of India only during the Nag Panchami or Naagula Chavithi festival. The cobra is deaf to the snake charmer's pipe, but follows the visual cue of the moving pipe and it can sense the ground vibrations from the snake charmer's tapping. Sometimes, for the sake of safety, the cobra will either be venomoid or the venom will have been milked prior to the snake charmer's act. The snake charmer may then sell this venom at a very high price. In the past Indian snake charmers also conducted cobra and mongoose fights. These gory fight shows, in which the snake was usually killed, are now illegal.[30]

Heraldry

Indian cobras were often a heraldic element in the official symbols of certain ancient princely states of India such as Gwalior, Kolhapur, Pal Lahara, Gondal, Khairagarh and Kalahandi, among others.[31]

Gallery

Indian cobra displaying an impressive hood

Indian cobra displaying an impressive hood Albino spectacled cobra

Albino spectacled cobra Binocellate cobra

Binocellate cobra

Cobra regurgitating bones and hair

Cobra regurgitating bones and hair

References

- "Naja naja". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Naja naja". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- Uetz, P. "Naja naja". The Reptile Database. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Whitaker, Romulus; Captain, Ashok (2004). Snakes of India: The Field Guide. Chennai, India: Draco Books. ISBN 81-901873-0-9.

- Mukherjee, Ashis K. (2012). "Green medicine as a harmonizing tool to antivenom therapy for the clinical management of snakebite: The road ahead". Indian J Med Res. 136 (1): 10–12. PMC 3461710. PMID 22885258.

- "Naja". The Free Dictionary. Princeton University. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Naja". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin) (10th ed.). Stockholm: Laurentius Salvius.

- Wüster, W. (1996). "Taxonomic changes and toxinology: systematic revisions of the Asiatic cobras (Naja naja species complex)". Toxicon. 34 (4): 399–406. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(95)00139-5. PMID 8735239.

- Smith, M.A. (1943). Reptilia and Amphibia, Volume 3: Serpentes. The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma, Including the Whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-Region. London, England: Taylor and Francis. pp. 427–436.

- Daniel, J.C. (2002). The Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. Oxford, England: Bombay Natural History Society and Oxford University Press. pp. 136–140. ISBN 0-19-566099-4.

- Wüster, W. (1998). "The Cobras of the genus Naja in India" (PDF). Hamadryad. 23 (1): 15–32. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "Naja naja". University of Adelaide.

- Mahendra, BC. (1984). Handbook of the snakes of India, Ceylon, Burma, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Agra : The Academy of Zoology. p. 412.

- Whitaker, Captain, Romulus, Ashok (2004). Snakes of India, The Field Guide. India: Draco Books. p. 354. ISBN 81-901873-0-9.

- Achyuthan, K. E.; Ramachandran, L. K. (1981). "Cardiotoxin of the Indian cobra (Naja naja) is a pyrophosphatase" (PDF). Journal of Biosciences. 3 (2): 149–156. doi:10.1007/BF02702658. S2CID 1185952.

- "IMMEDIATE FIRST AID for bites by Indian or Common Cobra (Naja naja naja)". Archived from the original on 2012-04-02.

- "LD50". Séan Thomas & Eugene Griessel – Dec 1999;Australian Venom and Toxin database. University of Queensland. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Brown Ph.D, John H. (1973). Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, IL USA: Charles C. Thomas Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- World Health Organization. "Zoonotic disease control: baseline epidemiological study on snake-bite treatment and management". Weekly Epidemiological Record. 62 (42): 319–320. ISSN 0049-8114.

- Snake-bites: a growing, global threat. BBC News (2011-02-22). Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

- Martz, W. (1992). "Plants with a reputation against snakebite". Toxicon. 30 (10): 1131–1142. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(92)90429-9. PMID 1440620.

- Daduang; Sattayasai, N.; Sattayasai, J.; Tophrom, P.; Thammathaworn, A.; Chaveerach, A.; Konkchaiyaphum, M. (2005). "Screening of plants containing Naja naja siamensis cobra venom inhibitory activity using modified ELISA technique". Analytical Biochemistry. 341 (2): 316–325. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.037. PMID 15907878.

- Katshu, M. Z. U. H.; Dubey, I.; Khess, C. R. J.; Sarkhel, S. (2011). "Snake Bite as a Novel Form of Substance Abuse: Personality Profiles and Cultural Perspectives". Substance Abuse. 32 (1): 43–46. doi:10.1080/08897077.2011.540482. PMID 21302184.

- Rodrigo, M. (October 9, 2016) Trials to start for home-grown anti-venom. sundaytimes.lk

- Singh, L (1972). "Evolution of karyotypes in snakes". Chromosoma. 38: 185–236.

- Suryamohan, Kushal; Krishnankutty, Sajesh P.; Guillory, Joseph; Jevit, Matthew; Schröder, Markus S.; Wu, Meng; Kuriakose, Boney; Mathew, Oommen K.; Perumal, Rajadurai C.; Koludarov, Ivan; Goldstein, Leonard D. (2020). "The Indian cobra reference genome and transcriptome enables comprehensive identification of venom toxins". Nature Genetics. 52 (1): 106–117. doi:10.1038/s41588-019-0559-8. ISSN 1546-1718.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Gutiérrez, José María; Calvete, Juan J.; Habib, Abdulrazaq G.; Harrison, Robert A.; Williams, David J.; Warrell, David A. (2017-09-14). "Snakebite envenoming". Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 3 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.63. ISSN 2056-676X.

- Snake myths. wildlifesos.com

- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1960. indialawinfo.com

- Heraldry of Madhya Pradesh. hubert-herald.nl

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Naja naja. |

- Serpents in Indian culture An article on Biodiversity of India website.