Ilya Ponomarev

Ilya Vladimirovich Ponomarev (Russian: Илья́ Влади́мирович Пономарёв; born 6 August 1975) is a Russian politician, former member of the State Duma and a technology entrepreneur.

Ilya Ponomarev | |

|---|---|

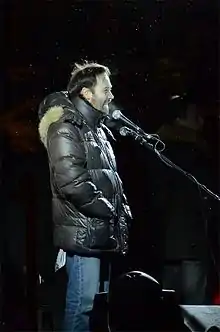

Ponomarev at the 2012 Horasis Global Russia Business Meeting | |

| Member of the State Duma | |

| In office 24 December 2011 – 10 June 2016 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ilya Vladimirovich Ponomarev 6 August 1975 Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Moscow, Russia) |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Political party | Left Front, Communist Party of Russia, A Just Russia |

| Occupation | Businessman, politician |

| Known for | Work with Skolkovo Foundation and hi-tech parks, sole vote against annexation of Crimea, position against Russian war in Ukraine, participation in protest movement in Russia |

He was the only member of the State Duma to vote against Russia's annexation of Crimea during the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[1][2] Ponomarev lives in exile in Kyiv, Ukraine.[3][4]

Early life and education

Ponomarev was born in Moscow.[5] He holds a BSc in Physics from Moscow State University and a Master of Public Administration from the Russian State Social University.[5] He started his career when he was 14 years old at the Institute for Nuclear Safety (IBRAE), Russian Academy of Sciences. Ponomarev was one of the founders of two successful high technology start-ups in Russia, the first one (RussProfi) when he was sixteen years old. His first job position was at the Institute for Nuclear Safety (IBRAE) at the Russian Academy of Sciences. In 1995 and 1996, Ponomarev acted as a representative of the networking software company Banyan Systems in Russia, creating one of the largest distributed networks in Russia for the now-defunct oil company Yukos. Following jobs at Schlumberger and Yukos in the late 1990s, he became a successful technology entrepreneur.[5][6] From 2002 to 2007, Ponomarev served as the chief information officer of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation.[7]

Career

Ponomarev held the role of vice president at Yukos Oil Company, at the time the largest Russian oil and gas corporation. Ponomarev's duties during those four years included those of corporate CIO, and chief executive of Yukos' subsidiary company ARRAVA IMC, which specialized in advanced oilfield technologies and services. Ponomarev later founded the Siberian Internet Company, which was the origin of prominent Internet projects in Russia such as Gazeta.ru. He also spent time as the Director for Business Development and Marketing for Schlumberger Oilfield Services, and the vice president for strategy, regional development, and government relations at IBS, which was at that time the largest Russian system integration and software consulting company.

From 2006 to 2007, Ponomarev served as the national coordinator for the "high-tech parks task force", a $6 billion private-public project to develop a network of small communities across the country to foster innovation and R&D activities.

In December 2007, Ponomarev was elected to the State Duma,[6] representing Novosibirsk. In the Duma, Ponomarev chaired the Innovation and Venture Capital subcommittee of the Committee for Economic Development and Entrepreneurship, and the Technology Development subcommittee of the Committee of Information Technologies and Communications. He introduced and secured passage of legalization of LLPs in Russia, the Net Businesses Act, and tax breaks for technology companies.

Ponomarev's political views are considered to be "unorthodox left": a progressive libertarian position. Some people describe him as "neo-communist",[6] and critics inside the Communist Party of Russia have identified him as "neotrotskyist".[8] Ponomarev's policy goals included the following:

- equal access to education, to create equal opportunities for everyone

- a non-restrictive government which would be gradually replaced by direct democracy

- promotion of social and business entrepreneurship and innovation to transform society

- visa-free travel and abolition of national borders

- replacement of the presidential republic in Russia with a parliamentary democracy, based on clear separation of power, a strong independent judiciary, and [9] federalism (with most taxes collected and spent by the regional governments)[10][11]

- protection of personal freedoms for oppressed groups, including increased rights and protections for women and LGBT people[12]

Internationally, Ponomarev advocated a broader "Northern Union" between the nations of Europe, the Americas, and the former USSR,[13] but strongly criticizes the American model of globalization exemplified by the IMF, the WTO and the G8 structures.[14] He describes his proposals as "social globalism",[11][15] and is critical of nationalism and clericalism.[16] He also criticized the privatization process in Russia, and blamed its neoliberal architects for the failure to establish a true democracy in Russia.[17]

From 2012 to 2014, Ponomarev was involved in International Business Development, Commercialization and Technology Transfer for the Skolkovo Foundation, managing the project initiated by Pres. Dmitry Medvedev to create SkolTech: a university established jointly by Russia and MIT.[18]

In April 2014, Ponomarev organized a coalition of opposition groups for the election of the Mayor of Novosibirsk, and withdrew his own candidacy to support the coalition's candidate: Communist Anatoly Lokot,[19] who won the election.[20] In May 2014, Ponomarev was appointed "Counselor for Strategic Development and Investments" for Novosibirsk .

He was a member of the Society of Petroleum Engineers (IT), Council for Foreign and Defense Policies, and the Council for National Strategy, and a fellow at the Open Russia foundation. He also chaired the Boards of Trustees of the Institute of Innovation Studies (a think tank working on legislation for high-tech industries) and the Open Projects Foundation (an investment vehicle for projects in crowdfunding, crowdsourcing and open government). In 2010 Ponomarev co-founded the Korean-Russian Business Council (KRBC).. In 2014, Ponomarev founded the Institute of Siberia, an analytical center focused on the regional development of Siberia.

During his political career, he was a member of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation from 2002 to 2007, and a member of the Central Committee of the social-democrat political party A Just Russia from 2007 to 2013. In the spring of 2014, he took part in forming an alliance between Greens and Social Democrats.

Opposition to Putin

In 2012, Ponomarev and fellow MP Dmitry G. Gudkov took a leadership role in street protests against Putin's rule.[6] Following the 4 March presidential election, in which Putin was elected for his third term as president, Ponomarev accused the government of rigging the election, claiming that it should have been close enough for a runoff.[21] In May, Ponomarev criticized Putin's decision to retain Igor Shuvalov in his cabinet despite a corruption scandal.[22] The following month, Ponomarev and Gudkov led a filibuster against a bill by Putin's United Russia party which allowed large fines to be imposed on anti-government protesters; though the filibuster was unsuccessful, the action attracted widespread attention.[6] Later, Ponomarev joined other political leaders in a successful challenge to the legislation before the Constitutional Court, overturning some of its provisions.

In June 2012, Ponomarev made a speech in the Duma in which he called United Russia members "crooks and thieves", a phrase originally used by anti-corruption activist Aleksei Navalny. In September of that year, Duma members voted to censure Ponomarev and bar him from speaking for one month. United Russia members also proposed charging him with defamation.[23]

In July, he strongly criticized the government response to the widespread flooding in Southern Russia Krymsk, which killed 172 people.[24] Together with several other civil activists, including Alyona Popova, Mitya Aleshkovsky, Danila Lindele and Maria Baronova, he organized a nationwide fundraising campaign which generated almost one million dollars in small donations to aid flood victims.

In December 2012, Ponomarev was the most vocal critic of the Dima Yakovlev Law, which restricted international adoption of Russian orphans (he was the only MP to vote against the bill in the first reading, and one of only eight opponents during the final reading). In 2013, Ponomarev was the only MP who refused to support the gay propaganda law. On 20 March 2014, Ponomarev was the only State Duma member to vote against the accession of Crimea to the Russian Federation following the 2014 Crimean crisis.[25]

Internet censorship

In 2012, Ponomarev supported[26][27] the Internet Restriction Bill, with the stated purpose of fighting online child pornography and drug sales, introduced by fellow Just Russia parliamentarian Yelena Mizulina. Critics compared the results to those of the Chinese Internet firewall:[28][29] a RosKomCenzura blocklist of censored pages, domain names, and IP addresses. Ponomarev claimed that he wished to ultimately limit government involvement in Internet regulation and allow more self-regulation,[30] but Maxim "Parker" Kononenko (a Russian blogger and journalist) accused[28][31] Ponomarev of acting in the commercial interests of a technology company which had Ponomarev's father Vladimir as a member of the board of directors[32] According to the law, all Internet providers are obliged to install expensive DPI (Deep Packet Inspection) hardware, which it was believed would be sold by said company. However, the company ultimately never sold any DPI servers , and Vladimir Ponomarev resigned from the board to avoid the appearance of impropriety.

In July 2013, Ponomarev stated during a meeting of the Russian Pirate Party that his support for Mizulina's bill had been a mistake[33]; he later voted against new initiatives by the Russian government to restrict Internet freedom, and became instrumental in the campaign against the "Russian version of SOPA".[34] Despite this, Ponomarev is portrayed by some other opposition activists (such as Alexey Navalny and Leonid Volkov) as a "censorship lobbyist", which Ponomarev claims is due to unrelated political disagreements and the struggle for influence over the Russian Internet community.[35]

Leonid Razvozzhayev incident

In October 2012, the pro-government news channel NTV aired a documentary which accused Ponomarev's aide Leonid Razvozzhayev of arranging a meeting between a former opposition leader, the Left Front's Sergei Udaltsov, and Givi Targamadze, a Georgian official, for the purpose of overthrowing President Vladimir Putin.[36] A spokesman for Russian investigators stated that the government was considering terrorism charges against Udaltsov,[36] and Razvozzhayev, Udaltsov, and Konstantin Lebedev, an assistant of Udaltsov's, were charged with "plotting mass riots".[37] Razvozzhayev fled to Kyiv, Ukraine, where he applied for asylum from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, but disappeared after leaving the office for lunch.[36] He resurfaced in Moscow three days later, where the website Life News recording him leaving a Moscow courthouse, shouting that he had been abducted and tortured.[36][38] A spokesman for Russia's Investigative Committee claimed that Razvozzhayev had not been abducted, but had turned himself in freely and volunteered a confession of his conspiracy with Udaltsov and Lebedev to cause widespread rioting.[36]

Vladimir Burmatov, a United Russia MP, called on Ponomarev to resign from the State Duma for his association with Razvozzhayev.[39]

In August 2014, both Udaltsov and Razvozzhayev were sentenced to four and a half years in prison.

Russian annexation of Crimea and accusations of embezzlement

Ponomarev was the only member of the State Duma to vote against annexation of Crimea during the 2014 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[2][1] Despite his criticism of the 2014 Ukrainian revolution as being driven by an alliance of neoliberals and nationalists, he justified his position in the Duma by saying that it was necessary to maintain friendly relations with the "brotherly Ukrainian nation" and avoid military confrontation, and argued that Russia's actions in Crimea would push Ukraine outside the traditional sphere of Russian influence and possibly provoke further expansion of NATO.[40] After the 445-1 vote, many people called for his resignation. He was also threatened with censure and expulsion, but responded that deputies cannot be prosecuted or removed because of the way they vote, and the parliament took no further action regarding the status of Ponomarev as deputy.[41] In August 2014, while he was in California, federal bailiffs froze Ponomarev's bank accounts and announced that they would not allow him to return to Russia, due to an ongoing investigation. He began living in San Jose, California,[42] but since 2016 is a permanent resident of Ukraine's capital Kyiv,[3][4] effectively in exile.[43] In April 2015, the Duma attempted to revoke his constitutional protection from criminal prosecution.[44]

Russian investigators claimed Ponomarev had embezzled 22 million rubles earmarked for the Skolkovo technology hub, an accusation Ponomarev describes as politically motivated. Russian investigators alleged that Skolkovo Vice-President Aleksey Beltyukov had paid Ponomarev about $750,000 for ten lectures and one research paper; . Ponomarev was initially not prosecuted for this because of his parliamentary immunity, but a court ordered him to return a part of the money. However, later in 2015, the Moscow Bauman Court heard Ponomaryov's case in absentia and decided to arrest him, issuing an international warrant. Despite not residing in Russia, Ponomarev continued to hold his parliamentary position, and would technically have remained an active member of the Duma until the September 2016 Duma election.[45][46]

On 10 June 2016, the State Duma impeached Ponomarev for truancy and not performing his duties. It was the first application of the controversial 2016 law that allows Duma to impeach its deputies.[47][48]

Personal life

Ponomarev is divorced. He has a son and a daughter.[5] His mother, Larisa Ponomareva, was an MP in the upper house of Russia's Parliament, the Federation Council, until September 2013, when she was forced to resign following her lone vote against the Dima Yakovlev Law.[6] Ponomarev is a nephew of Boris Ponomarev, Secretary for International Relations of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Ponomarev's grandfather Nikolai Ponomarev was the Soviet ambassador to Poland, and is believed to have prevented the USSR's invasion of the country along with Wojciech Jaruzelski, and paid with his career for doing that.

Ponomarev told The Daily Beast in April 2016 that he lived in Ukraine's capital Kyiv full-time.[4] He has received a Ukrainian temporary residence permit.[3]

After fellow former Russian MP Denis Voronenkov was shot and killed in Kyiv on 23 March 2017, Ponomarev was given personal protection by the Ukrainian Security Service.[49] Voronenkov was on his way to meet Ponomarev when he was shot.[49]

References

- Gorelova, Anastasia (25 March 2014). "Russian deputy isolated after opposing Crimea annexation". Reuters. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ""Unanimous Russia: Crimea Marks Open Season on Enemies" by Antonova, Maria - Russian Life, Vol. 57, Issue 3, May-June 2014 - Online Research Library: Questia". www.questia.com.

- (in Ukrainian) Former State Duma deputy investigation gave evidence in the case Yanukovich, Ukrayinska Pravda (27 December 2016)

- Putin’s Nemesis Dmitry Gudkov Dishes On His Achilles’ Heel, The Daily Beast (8 April 2016)

- "Ilya Ponomarev" (in Russian). A Just Russia. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- David M. Herszenhorn (23 June 2012). "Working Russia's Streets, and Its Halls of Power". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Francesca Mereu (11 December 2003). "Defeat Could Widen Split in Communist Party". The Moscow Times. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Ilya Ponomarev: When fathers fail, youth should continue". Versia (in Russian). Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Ilya Ponomarev and Alyona Popova: Stop feeding Moscow!". Tayga.info.

- "Ilya Ponomarev: program of the left". Ilya Ponomarev's blog. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- "Ilya Ponomarev and Karin Clement: What is modern left in Russia". Polit.ru. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Ilya Ponomarev about opposition, Siberian and agreements with Kremlin". Tayga.info.

- "Ilya Ponomarev: our main problem is ourselves". Moscow Vedomosti.

- Vasily Koltashov. "Two years of movement".

- "Kiev checkpoint for Russian left". Ilya Ponomarev's blog. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Ilya Ponomarev. "Modern left in Russia". Myshared.ru. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "MIT SkolTech Program". mit.edu. 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Илья Пономарев снялся с выборов мэра Новосибирска". Lenta. 28 March 2014.

- "Putin's party loses mayor race in Russia's third largest city". GlobalPost. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Phil Black (4 March 2012). "Putin Poised To Retake Russian Presidency". CNN. Retrieved 22 October 2012 – via Questia Online Library.

- Vladimir Isachenkov (21 May 2012). "Russian leader Putin names new Cabinet". Associated Press – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Andrew Roth (26 October 2012). "Russian Parliament Bars Opposition Lawmaker From Speaking". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Andrew E. Kramer (7 July 2012). "Heavy Rain in Southern Russia Brings Deadly Flash Floods". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Taylor, Adam (19 March 2014). "Meet the one Russian lawmaker who voted against making Crimea part of Russia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Сегодня в Думе рассматривают закон об интернете во втором (и в третьем) чтении. Правда о законе". Ponomarev's blog, Livejournal.com. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013.

- Lukas I. Alpert (11 July 2012). "Russian Duma Passes Internet Censorship Bill". Wall Street Journal.

- ""Kитайский интернет" в России, а также - почему Илья Пономарев голосовал за интернет-цензуру". Эхо России (общественно-политический журнал). 26 November 2012.

- "Заявление членов Совета в отношении законопроекта № 89417-6 «О внесении изменений в Федеральный закон "О защите детей от информации, причиняющей вред их здоровью и развитию"". Совет при Президенте Российской Федерации по развитию гражданского общества и правам человека. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- Ilya Ponomarev. "More over Internet self-governing law". Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- "Почему Илья Пономарев голосовал за реестр запрещенных сайтов". Идiотъ: Махим Кононенко's blog. 14 November 2012.

- "Полиция обыскала офис холдинга "Инфра инжиниринг" Константина Малофеева". Ведомости. 12 November 2013.

- "Пиратский Митинг Против Закона Против Интернета: Tupikin". Tupikin.livejournal.com. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Ilya Ponomarev. "Dirty tricks while passing new Internet legislation". Archived from the original on 27 June 2013.

- Ilya Ponomarev. "Why Navalny called me a jerk". Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- David M. Herzenhorn (22 October 2012). "Opposition Figure Wanted in Russia Says He Was Kidnapped and Tortured". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "Russia must investigate claims Leonid Razvozzhayev was abducted and tortured". Amnesty International. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Леонид Развозжаев признался в организации беспорядков на митинге 6 мая на Болотной площади в Москве (in Russian). Lifenews.ru. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Brian Whitmore (23 October 2012). "The Seizure Of Leonid Razvozzhayev". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "И снова про Украину - Илья Пономарёв". Ilya-ponomarev.livejournal.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Odd Man Out When Vote Was 445-1 on Crimea". The New York Times. 28 March 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- Rosie Gray (23 March 2015). "Russia Today Should Be Regulated As Lobbyists, Opposition Lawmaker Says". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

Last August, Ponomarev found out that he had been charged with illegally funneling money from a startup foundation he was involved with, charges he has said are "fabricated" and really meant as payback for his Crimea vote. Since then, Ponomarev has been living in San José.

- Taylor, Adam. "A year ago he was the only Russian politician to vote against annexing Crimea. Now he's an exile". The Washington Post. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Lawmakers Take Step to Remove Putin Critic", The New York Times, 7 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- "Lone Russian Lawmaker To Oppose Crimean Annexation Faces Fraud Probe". Radio Free Europe.

- "Ilya Ponomarev, a Lone Warrior Who Stands Up to Putin". Newsweek.

- "Илью Пономарева лишили мандата депутата Госдумы РФ". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 12 June 2016.

- "Госдума лишила Илью Пономарева депутатского мандата". TASS. 10 June 2016.

- Walker, Shaun (23 March 2017). "Denis Voronenkov: former Russian MP who fled to Ukraine shot dead in Kiev". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

External links

- Blog at LiveJournal