Hypothetical Axis victory in World War II

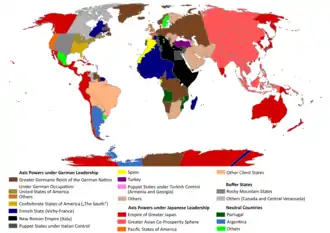

A hypothetical Axis victory in World War II has become a common concept of alternative history and counterfactual history. Such writings express ideas of what the world would be like had the Axis powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan won World War II. Numerous examples exist in several languages worldwide.[1][2]

The term Pax Germanica and Pax Japonica, Latin for "German peace" and "Japanese peace" respectively, is sometimes used for this theoretical period,[3] by analogy to similar terms for peaceful historical periods. In some cases, this term is used for a hypothetical Imperial German victory in World War I as well, having a historical precedent in Latin texts referring to the Peace of Westphalia.[4]

The subject of Axis supremacy as a fictional dramatic device began in the English-speaking world before the start of World War II, with Katharine Burdekin's novel Swastika Night coming out in 1937. Subsequent popular fictional depictions of an Axis-powers victory include: The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (1962), SS-GB by Len Deighton (1978), and Fatherland by Robert Harris (1992).

Some have viewed the enduring interest in the "what-ifs" of an Axis-powers victory as the result of the resonance of related themes; for example, how ordinary individuals deal with the humiliation and anger of being dominated.[1][5][6]

Depiction of Axis victory in fiction

Central themes and motifs

In terms of tone, the concept of a victory usually creates a background of depressing melancholy, audiences seeing plots unfold in a dark, strained atmosphere. Examples of writers using this device include Philip K. Dick, Stephen Fry, Robert Harris, and Philip Roth among many others.[1]

As noted by Helen White,[7] a hypothetical world where the Nazis won is by definition a far more harsh and grim place than the actual world. Still, many of the writers in this sub-genre leave the reader with at least some reason for hope. In Leo Rutman's Clash of Eagles, brave New Yorkers eventually rebel and throw off the Nazi Yoke; Len Deighton's SS-GB ends with the Americans raiding Nazi-occupied Britain and rescuing British nuclear scientists, with the British Resistance hoping for eventual liberation from across the Atlantic; at the end of Robert Harris' Fatherland, the protagonists manage to expose to the American public the hitherto hidden facts of the Jewish Genocide, thereby foiling the aging Hitler's hope for rapprochement with the US to solve Germany's growing economic crisis; Harry Turtledove's In the Presence of Mine Enemies depicts a world where the Nazis gained a complete military victory, but after two generations the regime undergoes a process of democratization similar to Perestroyka, and the secret Jews "hiding in plain sight" in the capital Berlin itself have some cautious reasons to expect a better future.

Conversely, The Ultimate Solution by Eric Norden presents the Nazi-dominated United States which is totally hideous and monstrous, with not the slightest room for hope left. Norden's plot concludes with the world about to be destroyed in an all-out nuclear war between Nazi Germany and its erstwhile ally Imperial Japan - and the plot is so constructed as to make the reader feel this might be a good idea.[8]

Early depictions

Swastika Night, authored by Katherine Burdekin under the pseudonym "Murray Constantine" in 1937, is a unique case given that it came out before World War II even began. It is thus a novel of future history rather than an "alternative" one. Writing in 2009 for The Guardian, journalist Darragh McManus remarked that "[t]hough a huge leap of imagination, Swastika Night posits a terrifyingly coherent and plausible" story-line. He also wrote, "And considering when it was published, and how little of what we know of the Nazi regime today was then understood, the novel is eerily prophetic and perceptive about the nature of Nazism". The journalist particularly noted the "violence and mindlessness" as well as the "irrationality and superstition" found in the post-victory dictatorship.[5]

In 1941, the travel-writer Henry Vollam Morton wrote I, James Blunt, a propaganda work set in September 1944 where Britain has lost the war and is under Nazi rule. The story is in the form of a diary describing the consequences of occupation, such as British workers being transported to Germany and Scottish shipyards building warships for an attack on the USA. The novella ends with an exhortation to the reader to make sure the story remains fiction.’[9]

The first Nazi-victory 'alternate history' as such, in any language, was published in 1945, months after Hitler's suicide and written by the Hungarian author Lászlo Gáspár.[1] Titled We, Adolf I (Adolf the First), the novel envisages German success after fighting in Stalingrad eventually leading to the victorious Hitler crowning himself a new modern 'Emperor'. Erecting in Berlin a huge Imperial Palace incorporating elements of the French Eiffel Tower and the U.S. Statue of Liberty among other spectacles, the narcissistic despot prepares a dynastic marriage with a Japanese princess to produce an heir who would rule the whole world.

Often known in English by the title The Last Jew, the Hebrew work Ha-Yehudi Ha'Aharon (היהודי האחרון) by the Revisionist Zionist physician and political activist Jacob Weinshall came out in Tel Aviv in 1946. In it, hundreds of years in the future, a completely Nazi-dominated world ruled by a "League of Dictators" discovers a last surviving Jew hiding in Madagascar. The Nazi rulers plan to publicly execute this last Jew during the forthcoming Olympic Games. However, before this can take place, the Moon moves close to the Earth as a result of the Nazis' misguided attempt to colonize it. The catastrophe causes the end of human civilization and thus of Nazi rule. Weinshall's Hebrew text, as of 2000, has never received a full, formal translation into other languages.[10] The novel should not be confused with Yoram Kaniuk's novel The Last Jew, which has been translated to English.[11]

The work Peace in Our Time explored a fascist-dominated London and the deleterious effects of occupation on regular people. English playwright and Secret Service agent Noël Coward, whose name appeared on a Gestapo arrest list in the event of a ground invasion of the UK, authored the drama, and it received its stage debut in 1947. Although facing a muted response at first, lingering interest in Coward's work, as well as the specific themes of Peace in Our Time, have meant that subsequent productions have gone on, even into the 21st century.[6]

Later depictions

Additional notable depictions of Axis victory include:

Literature

- The Sound of His Horn by Sarban (1952)

- Living Space by Isaac Asimov (1956)

- The Big Time by Fritz Leiber (1957)

- The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick (1962)

- The Iron Dream by Norman Spinrad (1972) depicts a science fiction/fantasy allegory of a Nazi victory

- The Ultimate Solution by Eric Norden (1973)

- SS-GB by Len Deighton (1978)

- The Divide by William Overgard (1980)

- The Proteus Operation by James P. Hogan (1985)

- Thor Meets Captain America by David Brin (1986)

- The Last Article by Harry Turtledove (1988)

- Clash of Eagles by Leo Rutman (1990)

- Timewyrm: Exodus (Doctor Who novel) by Terrance Dicks (1991)

- Fatherland, by Robert Harris (1992)

- No Retreat by John Bowen (1994)

- '48 by James Herbert (1996)

- Attentatet i Pålsjö skog by Hans Alfredson (1996)

- Making History by Stephen Fry (1996)

- Patton's Spaceship by John Barnes (part of The Timeline Wars series (1997))

- Against the Day by Michael Cronin (1999)

- After Dachau by Daniel Quinn (2001)

- Collaborator by Murray Davies (2003)

- In the Presence of Mine Enemies by Harry Turtledove (2003, the first 21 pages were originally a short story published in 1992)

- Mobius Dick by Andrew Crumey (2004)

- The Plot Against America by Philip Roth (2004)

- Warlords of Utopia by Lance Parkin (2004)

- Farthing, Ha'penny, and Half a Crown, series by Jo Walton (2006–2008)

- Resistance by Owen Sheers (2007)

- The Conquistador's Hat by John Maddox Roberts (2011)

- Dominion by C. J. Sansom (2012)

- A Kill in the Morning by Graeme Shimmin (2014)

- The Madagaskar Plan by Guy Saville (2015)

- Mecha Samurai Empire series by Peter Tieryas (2016–2020)

Counterfactual scenarios are also written as a form of academic paper rather than necessarily as fiction and/or novel-length fiction.

- What If?: The World's Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been contains "How Hitler Could Have Won the War" by John Keegan.

- Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals, edited by Niall Ferguson, contains "Hitler's England: What if Germany had invaded Britain in May 1940?" by Andrew Roberts and Niall Ferguson, plus "Nazi Europe: What if Nazi Germany had defeated the Soviet Union?" by Michael Burleigh.

The All About History Bookazine series came out with What if...Book of Alternate History (2019). Among the articles are What if...Germany had won the Battle of Britain? and What if...The Allies had lost the Battle of the Atlantic?

Film

- It Happened Here (1966), a British film directed by Kevin Brownlow.[12]

- Philadelphia Experiment II (1993)

- Fatherland (1994), based on the 1992 novel.

- Jackboots on Whitehall (2010)

- Resistance (2011)

Television

- The Other Man (1964)

- Star Trek: The Original Series: "The City on the Edge of Forever" (1967)

- An Englishman's Castle (1978)

- Darkroom_(TV_series): "Stay Tuned, We'll Be Right Back" (1981)

- Justice League: "The Savage Time" (2002)

- Star Trek: Enterprise: "Zero Hour"/"Storm Front" (2004)

- Misfits: Season 3, Episode 4 (2011)

- The Man in the High Castle (2015–2019), an Amazon Studios series based on the 1962 novel.

- SS-GB (2017), a BBC miniseries based on the 1978 novel.

- Crisis on Earth-X (2017), four-part crossover episode of Supergirl, Arrow, The Flash, and DC's Legends of Tomorrow.

- The Plot Against America (2020)

Comics

- "Blitzkrieg 1972", issue 155 of The Incredible Hulk (September 1972), takes place in a battle-torn New York City, where German Nazi forces, from their headquarters on Wall Street, are increasingly defeating the outnumbered US Army forces desperately defending the city - until the Hulk comes to take a hand in the fighting and confront the super-Nazi Captain Axis.

- In DC Comics, Earth X is an alternative Earth in which the Nazis won World War II.

- In the 2003-2004 Captain America story arc Cap Lives (Captain America Vol. 4, issues 17-20), Captain America awakens from suspended animation in 1964 to find that - due to a temporal anomaly - Nazi Germany has won WWII and conquered much of the world, including the United States. After dropping a nuclear bomb on the US, Nazi Germany took control of North America, renaming New York City as "New Berlin" and declaring New Berlin the capital of Nazi America. The Red Skull has become the Führer of the so-called "New Reich" and seeks to create an army of blonde, Aryan supermen or super soldiers based on Captain America's DNA. Alongside American resistance fighters that include Bucky Barnes, Nick Fury and his Howling Commandos, Peter Parker, Ben Grimm, Johnny Storm, Sue Storm, Reed Richards, Hank Pym, Janet van Dyne, Tony Stark, Donald Blake, Bruce Banner, Matt Murdock, Luke Cage, Frank Castle, and Stephen Strange, Captain America fights against the New Reich and succeeds in returning to the timeline in which he is originally meant to be.[13][14]

- An alternate reality (designated as Earth 9907) in which the Red Skull survived and assumed leadership of the failing Third Reich, leading it into total world domination, also appears in the A-Next comic series by Marvel Comics.[15]

Video games

- Rocket Ranger (as a background story/alternate reality) by Cinemaware (1988)

- Turning Point: Fall of Liberty by Spark Unlimited (2008)

- Battlestations: Pacific by Eidos Interactive (2009)

- Wolfenstein: The New Order by MachineGames (2014)

- Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus by MachineGames (2017)

- Wolfenstein: Youngblood by MachineGames (2019)

Cultural studies

Academics, such as Gavriel David Rosenfeld in The World Hitler Never Made: Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism (2005), have researched the media representations of 'Nazi victory'.[16]

See also

- American Civil War alternate histories

- If Day

- Kantokuen

- Operation Sea Lion in fiction

- Proposed Japanese invasion of Australia during World War II

- Palestine Final Fortress (possible Nazi occupation of Palestine)

- Axis powers negotiations on the division of Asia

- Ural Mountains in Nazi planning

- Generalplan Ost

References

- Manheim, Noa. "Alternative History: What Might Have Been Had Hitler Won?". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2017-08-17. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Fred Bush (July 15, 2002). "The Time of the Other: Alternate History and the Conquest of America". Strange Horizons. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- "Carl Tighe: Pax Germanica - the Future Historical. Journal of European Studies, Vol. 30, 2000". Archived from the original on 2020-04-04. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- "CAPUT LXVIII. Chronologia." Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine in CAMENA. See for years 1648 et 1649.

- McManus, Darragh (12 November 2009). "Swastika Night: Nineteen Eighty-Four's lost twin". The Guardian.

- Hardy, Michael (September 30, 2014). "Review: Peace in Our Time Is a Play For Our Time". Houstonia. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Dr. Helen White "Why are we attracted to nightmares of Nazi victory? Wasn't the actual Nazi history bad enough?" in Alan Wiederman (ed.) "Round-Up of New Essays in Twentieth History Popular Culture"

- Michael Kornfeld "Face It, Sometimes There Is Just No Happy Ending, None Whatsoever" in Alan Wiederman (ed.) "Round-Up of New Essays in Twentieth History Popular Culture"

- https://hvmorton.com/2020/01/18/i-james-blunt-by-kenneth-fields/

- Eli Eshed, "Israeli Alternate Histories" (in Hebrew) published by the Israeli Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy, November 2, 2000

- Kaniuk, Yoram (2007-12-01). The Last Jew: A Novel. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. ISBN 9781555848385.

- "World War Two: The Rewrite". The Independent. April 23, 2006. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2009-06-26.

- Hölbling, Walter; Heller, Arno (2004). What is American?: New Identities in U.S. Culture. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783825877347.

- "Marvel Knights Captain America Vol. 4: Cap Lives". Marvel Masterworks.

- A-Next #11-12

- Moorcock, Michael (July 2005). "If Hitler had won World War Two…".

Further reading

- Rosenfeld, Gavriel David. The World Hitler Never Made. Alternate History and the Memory of Nazism (2005).

- Tighe, C., "Pax Germanica in the future-historical" in Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik, pp. 451–467.

- Tirghe, Carl. "Pax Germanicus in the future-historical". In Travellers in Time and Space: The German Historical Novel (2001).

- Winthrop-Young, Geoffrey. "The Third Reich in Alternate History: Aspects of a Genre-Specific Depiction of Nazism". In Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 39 no. 5 (October 2006).

- Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Martin Cüppers. Nazi Palestine. The Plans for the Extermination of the Jews in Palestine, New York: Enigma Books with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2010.