Hugh Broughton

Early life

He was born at Owlbury, Bishop's Castle, Shropshire. He called himself a Cambrian, implying Welsh blood in his veins. He was educated by Bernard Gilpin at Houghton-le-Spring and at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he matriculated in 1570.[1] The foundation of his Hebrew learning was laid, in his first year at Cambridge, by his attendance on the lectures of the French scholar Antoine Rodolphe Chevallier.

Fellowship at Cambridge

Broughton graduated B.A. in 1570, and became fellow of St John's College and afterwards of Christ's College. He had influential patrons at the university; Sir Walter Mildmay made him an allowance for a private lectureship in Greek, and Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, supported him with means for study. He was elected one of the taxers of the university, and obtained a prebend and a readership in divinity at Durham. On the grounds of his holding a prebend, he was deprived of his fellowship in 1579, but was reinstated in 1581, at the instance of Lord Burghley, the chancellor, who, moved by the representations of Richard Barnes, the Bishop of Durham, the Earl of Huntingdon, and Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, overcame the opposition of John Hatcher, the vice-chancellor, and Edward Hawford, master of Christ's. He resigned the office of taxer, and does not seem to have returned to the university.

Time in London

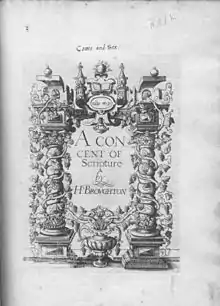

Broughton came to London, where he spent time in intense study, and distinguished himself as a preacher of puritan sentiments in theology. He is said to have predicted, in one of his sermons (1588), the scattering of the Spanish Armada. He found friends among the citizens, especially in the family of the Cottons, with whom he lived, and whom he taught Hebrew. In 1588 appeared his first work, A Concent of Scripture, dedicated to the queen. John Speed, the historian, saw the book through the press. The Concent was attacked in public prelections by John Rainolds at Oxford, and Edward Lively at Cambridge. Broughton appealed to the queen (to whom he presented a special copy of the book on 17 November 1589), to John Whitgift, and to John Aylmer, bishop of London, asking to have the points in dispute between Rainolds and himself determined by the authority of the archbishops and the two universities. He began weekly lectures in his own defence to an audience of between 80 and 100 scholars, using the Concent as a text-book. The privy council allowed him to deliver his lectures (as Chevallier had done before) at the east end of St Paul's Cathedral, until some of the bishops complained of his audiences as conventicles. He then moved his lecture to a room in Cheapside, and then to Mark Lane, and elsewhere. Insecurity based on fear of the high commission made him anxious to leave the country.

Years of travel

Broughton left for Germany at the end of 1589 or beginning of 1590, taking with him a pupil, Alexander Top, a young country gentleman. Broughton on his travels took part in disputations against Catholics, and engaged in religious discussion with several rabbis. At Frankfurt, early in 1590, he disputed in the synagogue with Rabbi Elias. He was at Worms in 1590, and returned next year to England. His letter of 1590–1591 to Lord Burghley asks permission to go abroad to make use of King Casimir's library.

But he remained in London, where he met Rainolds, and agreed with him to refer their differing views about the harmony of scripture chronology to the arbitration of Whitgift and Aylmer. Nothing came of this, and Whitgift undermined Broughton with Elizabeth. In 1592 Broughton was again in Germany, and he continued to engage in discussion, to lobby for preferment, to increase his reputation with some scholars, and to offend others such as Joseph Justus Scaliger. He wrote against Theodore Beza fiercely in Greek; he held episcopacy to be apostolic.

Between 1605 and 1608 Broughton also played a central role in the establishment of the English Reformed Church in Amsterdam, which had been founded towards the end of 1605 for the "English people resident in Amsterdam and professing the Reformed religion."[2]

Slights under James I

In 1603 he preached before Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, at Oatlands, on the Lord's Prayer. He soon returned to Middelburg, and became preacher there to the English congregation. This was written in the month following the king's letter (22 July) appointing fifty-four learned men for the revision of the translation of the Bible. Broughton's old adversary, Rainolds, had been more successful than he in pressing upon the authorities the need of a revision, and when the translators were appointed, Broughton, to his intense chagrin, was not included among them.

Subsequently, he criticised the new translation unsparingly, after his manner. His bitter pamphlet against Richard Bancroft did not improve his recognition as a scholar. Ben Jonson satirised him in Volpone (1605), and especially in The Alchemist (1610). He continued to write and publish assiduously. His translation of the Book of Job (1610) he dedicated to the king.

Return to England and death

In 1611 he was suffering from consumption. He made his last voyage to England, arriving at Gravesend in November. He told his friends he had come to die, and wished to die in Shropshire, where his old pupil Sir Rowland Cotton had a seat. His strength, however, was not equal to the journey. He wintered in London, and in the spring removed to Tottenham. Here he lingered till autumn, in the house of Benet, a Cheapside linen draper. His death occurred on 4 August 1612. He was buried in London, at St. Antholin's, on 7 August, James Speght preaching his funeral sermon. He had married a niece of his pupil, Alexander Top, named Lingen.

Works

In 1588 he published his first work, A Concent of Scripture. It dealt with biblical chronology and textual criticism, was attacked at both universities, and the author was obliged to defend it in a series of lectures.

While at Middelburg he printed An Epistle to the learned Nobilitie of England, touching translating the Bible from the Original, 1597. The project of better version of the Bible was one on which he had already addressed the queen. His plan, as given in a letter dated 21 June 1593, was to do the work in conjunction with five other scholars. Only necessary changes were to be made, but the principle of harmonising the scripture was to prevail, and there were to be short notes. Though his scheme was backed up by lords and bishops, his application for the means of carrying it out was unsuccessful. In a letter to Burghley, of 11 June 1597, he blamed Whitgift for hindering his proposed new translation.

In 1599 he printed his 'Explication' of the article respecting Christ's descent into hell. It was a topic he had touched upon before, maintaining with his usual vigour (against the Augustinian view, espoused by most Anglican divines) that Hades never meant the place of torment, but the state of departed souls.

In 1610 his A Revelation of the Holy Apocalyps was printed in which he argues that Hades has only two places, heaven and hell, and that purgatory is non-existent.

Some of his works were collected and published in a large folio volume in 1662, with a sketch of his life by John Lightfoot.[3] Some of his theological manuscripts are in the British Library.

References

- "Broughton, Hugh (BRTN569H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Alice C. Carter, The English Reformed Church in Amsterdam in the Seventeenth Century (Amsterdam: Scheltema & Holkema NV, 1964), pp. 15-25.

- Under the title, The Works of the Great Albionean Divine, renowned in many Nations for Rare Skill in Salems and Athens Tongues, and Familiar Acquaintance with all Rabbinical Learning, Mr. Hugh Broughton, 1662. The volume is arranged in four sections or 'tomes;' prefixed is his life; Speght's funeral sermon is given in the fourth tome; appended is an elegy by W. Primrose.

- Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Broughton, Hugh". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Broughton, Hugh". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Broughton, Hugh". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Broughton, Hugh". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- "Map Showing the Dispersal of the Children of Noah". Of the Incomparable Treasure of the Holy Scriptures: An Exhibit of Historic Bible-related Materials from the Collection of the Andover-Harvard Theological Library. Retrieved 28 June 2014. This page, which displays an image from Broughton's A Concent of Scripture, contains a brief biography of the scholar.