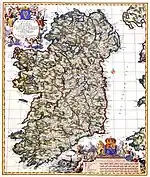

History of the Jews in Ireland

The history of the Jews in Ireland extends back nearly a thousand years. Although the Jewish community in Ireland has always been small in numbers (not exceeding 5,500 since at least 1891), it is well established and has generally been well-accepted into Irish life. Jews in Ireland have historically enjoyed a relative tolerance that was largely absent elsewhere in Europe.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,557 (2016) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Dublin, Cork | |

| Languages | |

| English, Hebrew, Yiddish, Irish | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lithuanian Jews, Ashkenazi Jews |

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ireland |

|

|

|

Early history

The earliest reference to the Jews in Ireland was in the year 1079. The Annals of Inisfallen record "Five Jews came from overseas with gifts to Toirdelbach [Toirdelbach Ua Briain, the king of Munster], and they were sent back again oversea".[1]

No further reference is found until the 1169 Norman invasion of Ireland launched by Strongbow (Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke) in defiance of a prohibition by Henry II of England. Strongbow seems to have been assisted financially by a Jewish moneylender, for under the date of 1170 the following record occurs: "Josce Jew of Gloucester owes 100 shillings for an amerciament for the money which he lent to those who against the king's prohibition went over to Ireland".[2]

By 1232, there was probably a Jewish community in Ireland, as a grant of 28 July 1232 by King Henry III to Peter de Rivel gives him the office of Treasurer and Chancellor of the Irish Exchequer, the king's ports and coast, and also "the custody of the King's Judaism in Ireland".[3] This grant contains the additional instruction that "all Jews in Ireland shall be intentive and respondent to Peter as their keeper in all things touching the king".[4] The Jews of this period probably resided in or near Dublin. In the Dublin White Book of 1241, there is a grant of land containing various prohibitions against its sale or disposition by the grantee. Part of the prohibition reads "vel in Judaismo ponere" (prohibiting it from being sold to Jews). The last mention of Jews in the "Calendar of Documents Relating to Ireland" appears about 1286. After the 1290 Edict of Expulsion of Jews from England, Jews living in the English Pale around Dublin may have had to leave English jurisdiction, although there is no evidence for this. It would not have been difficult for Jews to defy the 1290 Edict by moving beyond English settlement into the Gaelic Irish areas that England did not control.

Jews were certainly living in Ireland long before Oliver Cromwell in 1657 revoked the English Edict of Expulsion. A permanent settlement of Jews was definitely established in the late 15th century. Following their expulsion from Portugal in 1497, some of these Sephardic Jews settled on Ireland's south coast. One of them, William Annyas, was elected mayor of Youghal, County Cork, in 1555. Francis Annyas (Ãnes), was a three-time Mayor of Youghal in 1569, 1576 and 1581.[5] Ireland's first synagogue was founded in 1660 near Dublin Castle. A plot of land was acquired in 1718[6] as a burial ground, called Ballybough Cemetery, it was the first Jewish cemetery. It is situated in the Fairview district of Dublin, where there was a small Jewish colony.[7]

18th and 19th century

In December 1714, the Irish philosopher John Toland issued a pamphlet entitled Reasons for Naturalizing the Jews in Great Britain and Ireland.[8][9] In 1746 a bill was introduced in the Irish House of Commons "for naturalising persons professing the Jewish religion in Ireland". This was the first reference to Jews in the House of Commons up to this time. Another was introduced in the following year, agreed to without amendment, and presented to the Lord Lieutenant to be transmitted to England but it never received the royal assent. These Irish bills, however, had one very important result; namely, the formation of the Committee of Diligence, which was organized by British Jews at this time to watch the progress of the measure. This ultimately led to the organization of the Board of Deputies,[10] an important body which has continued in existence to the present time. Jews were expressly excepted from the benefit of the Irish Naturalisation Act of 1783. The exceptions in the Naturalisation Act of 1783 were abolished in 1846. The Irish Marriage Act of 1844 expressly made provision for marriages according to Jewish rites.

Daniel O'Connell is best known for the campaign for Catholic Emancipation, but he also supported similar efforts for Jews. In 1846, at his insistence, the British law "De Judaismo", which prescribed a special dress for Jews, was repealed. O’Connell said: "Ireland has claims on your ancient race, it is the only country that I know of unsullied by any one act of persecution of the Jews".

During the Great Famine (1845–1852), in which approximately 1 million Irish people died, many Jews helped to organize and gave generously towards famine relief.[11][12] A Dublin newspaper, commenting in 1850, pointed out that Baron Lionel de Rothschild and his family had,

...contributed during the Irish famine of 1847 ... a sum far beyond the joint contributions of the Devonshires, and Herefords, Lansdownes, Fitzwilliams and Herberts, who annually drew so many times that amount from their Irish estates.[13]

In 1874, Lewis Wormser Harris was elected to Dublin Corporation as Alderman for South Dock Ward. Two years later he was elected as Lord Mayor of Dublin, but died 1 August 1876 before he took office.[14]

20th century

There was an increase in Jewish immigration to Ireland during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1871, the Jewish population of Ireland was 258; by 1881, it had risen to 453. Most of the immigration up to this time had come from England or Germany. A group who settled in Waterford were Welsh, whose families originally came from Central Europe.[15] In the wake of the Russian pogroms there was increased immigration, mostly from Eastern Europe (in particular Lithuania). By 1901, there were an estimated 3,771 Jews in Ireland, over half of them (2,200) residing in Dublin. By 1904, the total Jewish population had reached an estimated 4,800. New synagogues and schools were established to cater to the immigrants, many of whom established shops and other businesses. Many of the following generations became prominent in business, academic, political, and sporting circles.

The Jewish population of Ireland reached around 5,500 in the 1940s, but according to the 2016 census had declined to about 2,500 in 2016, mainly due to assimilation and emigration. The Irish Jewish population saw a large drop in numbers in 1948 after the establishment of Israel; with a large number of Irish Jews moving there out of ideological and religious convictions. In subsequent decades, more Jews would also emigrate to Israel, the United Kingdom, and the United States due to the decline of Jewish life in Ireland and for better economic prospects. In addition, rates of intermarriage and assimilation, including conversion to Catholicism in order to marry, were also high.

The Republic of Ireland currently has three synagogues in Dublin. There is a further synagogue in Belfast in Northern Ireland. The synagogue in Cork closed in 2016.

Limerick Boycott

The economic boycott waged against the small Jewish community in Limerick City in the first decade of the 20th century is known as the Limerick Boycott (and sometimes known as the Limerick Pogrom) and caused many Jews to leave the city. It was instigated by an influential Redemptorist priest, Father John Creagh who called for a boycott during a sermon in January 1904. A teenager, John Raleigh, was arrested by the police and briefly imprisoned for attacking the Jews' rebbe, but returned home to a welcoming throng. According to an RIC report, 5 Jewish families left Limerick "owing directly to the agitation" and 26 families remained. Some went to Cork, where trans-Atlantic passenger ships docked at Cobh (then known as Queenstown). They intended to travel to America. Gerald Goldberg, a son of this migration, became Lord Mayor of Cork in 1977.

The boycott was condemned by many in Ireland, among them the influential Standish O'Grady in his paper All Ireland Review, depicting Jews and Irish as "brothers in a common struggle", though using language differentiating between the two. The Land Leaguer Michael Davitt (author of The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia), in the Freeman's Journal, attacked those who had participated in the riots and visited homes of Jewish victims in Limerick.[16] His friend, Corkman William O'Brien MP, leader of the United Irish League and editor of the Irish People, had a Jewish wife, Sophie Raffalovic.

Father Creagh was moved by his superiors initially to Belfast and then to an island in the Pacific Ocean. In 1914 he was promoted by the Pope to be Vicar Apostolic of Kimberley, Western Australia, a position he held until 1922.[17] He died in Wellington, New Zealand in 1947. Joe Briscoe, son of Robert Briscoe, the Dublin Jewish politician, describes the Limerick episode as “an aberration in an otherwise almost perfect history of Ireland and its treatment of the Jews”.[18]

Since 1983, several commentators have questioned the traditional narrative of the event, and especially whether the event's description as a pogrom is appropriate.[19][20] Historian Dermot Keogh sympathised with the use of the term by the Jews who experienced the event, and respected its use by subsequent writers, but preferred the term "boycott".[21][22] Creagh's anti-Semitic campaign, while virulent, did not result in the decimation of Limerick's Jewish community. The 1911 census records that, not only were 13 of the remaining 26 families still resident in Limerick six years later but that 9 new Jewish families had joined them.[23] The Jewish population numbered 122 persons in 1911 as opposed to 171 in 1901. This had declined to just 30 by 1926.

War of Independence

Many Irish Jews supported the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the First Dail during the Irish War of Independence. Michael Noyk was a Lithuanian-born solicitor who became famous for defending captured Irish Republicans such as Sean MacEoin. Robert Briscoe was a prominent member of the IRA during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. He was sent by Michael Collins to Germany in 1920 to be the chief agent for procuring arms for the IRA. Briscoe proved to be highly successful at this mission, and arms arrived in Ireland in spite of the British blockade.[24]

Irish Free State Senate

In an effort to provide minority communities with political representation in parliament (as was the case with minority Christian denominations) Ellen Cuffe (Countess of Desart), a member of the Jewish community, was appointed for a twelve-year term by W. T. Cosgrave to the Irish Senate in 1922. She sat as an independent member until her death in 1933.[25] She was also an advocate for the Irish language and served as President of the Gaelic League.

Irish Government

The Irish Constitution of 1937 specifically gave constitutional protection to Jews. This was considered to be a necessary component to the constitution by Éamon de Valera because of the treatment of Jews elsewhere in Europe at the time.[26]

The reference to the Jewish Congregations in the Irish Constitution was removed in 1973 with the Fifth Amendment. The same amendment removed the 'special position' of the Catholic Church, as well as references to the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church, the Methodist Church, and the Religious Society of Friends.

Kindertransport to Northern Ireland

A committee organized the Kindertransport. About ten thousand unaccompanied children aged between three and seventeen from Germany and Czechoslovakia were permitted entry into the United Kingdom without visas in 1939. Some of these children were sent to Northern Ireland. Many of them were looked after by foster parents but others went to the Millisle Refugee Farm (Magill's Farm, on the Woburn Road) which took refugees from May 1938 until its closure in 1948.[27]

World War II and aftermath

The Irish envoy to Berlin, Charles Bewley, appointed in 1933, became an admirer of Hitler and National Socialism. His reports contained incorrect information on the treatment of Jews in Germany, and he was against allowing Jews to move to Ireland. After being reprimanded by Dublin, he was dismissed in 1939.[28]

The Irish state was officially neutral during World War II, known within the Republic of Ireland as "The Emergency" although it is estimated that about 100,000 men from the state took part on the side of the Allies,[29] while a handful may have taken the part of their opponents. In Rome, T.J. Kiernan, the Irish Minister to the Vatican, and his wife, Delia Murphy (a noted traditional ballad singer), worked with the Irish priest Hugh O'Flaherty to save many Jews and escaped prisoners of war. Jews conducted religious services in the church of San Clemente of the ‘Collegium Hiberniae Dominicanae’, which had Irish diplomatic protection.[30]

There was some domestic anti-Jewish sentiment during World War II, most notably expressed in a notorious speech to the Dáil in 1943, when newly elected independent TD Oliver J. Flanagan advocated "routing the Jews out of the country".[31] On the other hand, Henning Thomsen, the German chargé d'affaires, officially complained of press commentaries. In February 1939, he protested against the Bishop of Galway who had issued a pastoral letter, along similar lines, accusing Germany of "violence, lying, murder and the condemning of other races and peoples".[32]

There was some official indifference from the political establishment to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust during and after the war. This indifference would later be described by Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform Michael McDowell as being "antipathetic, hostile and unfeeling".[33] Dr. Mervyn O'Driscoll of University College Cork reported on the unofficial and official barriers that prevented Jews from finding refuge in Ireland although the barriers have been down ever since:

Although overt anti-Semitism was not typical, the southern Irish were indifferent to the Nazi persecution of the Jews and those fleeing the Third Reich....A successful applicant in 1938 was typically wealthy, middle-aged, or elderly, single from Austria, Roman Catholic and desiring to retire in peace to Ireland and not engage in employment. Only a few Viennese bankers and industrialists met the strict criterion of being Catholic, although possibly of Jewish descent, capable of supporting themselves comfortably without involvement in the economic life of the country.[34]

Two Irish Jews, Ettie Steinberg and her infant son, are known to have been killed during the Holocaust, which otherwise did not substantially directly affect the Jews actually living in Ireland. The Wannsee Conference listed the 4,000 Jews of Ireland to be among those marked for killing in the Holocaust.

Post-war, Jewish groups had great difficulty in getting refugee status for Jewish children, whereas the Irish Red Cross had no difficulties with Operation Shamrock, which brought over 500 Christian children, mainly from the Rhineland.[35] The Department of Justice explained in 1948 that:

It has always been the policy of the Minister for Justice to restrict the admission of Jewish aliens, for the reason that any substantial increase in our Jewish population might give rise to an anti-Semitic problem.[36]

However, De Valera overruled the Department of Justice and the 150 refugee Jewish children were brought to Ireland in 1948. Earlier, in 1946, 100 Jewish children from Poland were brought to Clonyn Castle in County Meath[37] by Solomon Schonfeld.[38] In 2000 many of the Clonyn Castle children returned for a reunion. In 1952 he again had to overrule the Department of Justice to admit five Orthodox families who were fleeing the Communists. In 1966, the Dublin Jewish community arranged the planting and dedication of the Éamon de Valera Forest in Israel, near Nazareth, in recognition of his consistent support for Ireland's Jews.[39]

In 2006, Tesco, a British supermarket chain, had to apologize for selling the notorious antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion in its stores in Britain and Ireland. Sheikh Dr Shaheed Satardien, head of the Muslim Council of Ireland, said this was effectively "polluting the minds of impressionable young Islamic people with hate and anger towards the Jewish community".[40]

Sport

Bethel Solomons played rugby union for Wesley College and for Ireland earning 10 caps from 1907–1910.[41][42]

The Lithuanian born Louis Bookman (1890–1943) who moved to Ireland as a child, played soccer at international level for Ireland (winning the Home International Championship in 1914), as well as playing at club level for Shelbourne and Belfast Celtic, he also played cricket for Railway Union Cricket Club, the Leinster Cricket Club and for the Irish National Cricket Team.

Louis Collins Jacobson played cricket for Ireland opening the innings on 12 occasions, and also at club level in Dublin as the opening bat for Clontarf C.C. and earlier, for Carlisle Cricket Club in Kimmage which was made up of members of the Dublin Jewish community.[43]

Dublin Maccabi was a Soccer team in Kimmage/Terenure/Rathgar. They played in the Dublin Amateur Leagues; only players who were Jewish played for them. Maccabi played their games in the KCR grounds which opened in the 1950s. They disbanded in 1995 due to dwindling numbers and disputes over fees, and many of their players joined the Parkvale F.C.

For a time Dublin Jewish Chess Club played in the Leinster leagues, in 1936 winning the Ennis Shield being promoted to play in Division 1 Armstrong Cup. An earlier Jewish team had played in the 1908 Armstrong Cup. Riga born Philip Baker(1880-1932) was Irish Chess Champion in 1924, 1927, 1928, and 1929.

There was also a Dublin Jewish Boxing Club, on the south side of the city. It was based for its whole existence of many years, in the basement of the Adelaide Road Synagogue, which was the largest synagogue in the country. Many fine boxers were produced, amongst whom were Sydney Curland, Freddie Rosenfield, Gerry Kostick, Frank and Henry Isaacson, and Zerrick Woolfson. As a boxer, Gerry Kostick represented Ireland at the 1949 Maccabiah Games and the 1953 Maccabiah Games and, representing Trinity College Dublin, won two Universities Athletic Union titles. Kostick also played rugby and football for Carlisle for over ten years, while Woolfson also played cricket for Carlisle C.C. for several years, and, in 1949 for Dublin University, when he bowled a hat-trick in his first match. As reported in the newspapers, he dismissed J.V.Luce, Mick Dargan, and Gerry Quinn with 3 successive balls. They were all very competent, current international players. He also played first division table-tennis for Anglesea T.T.C. as the #3 player, joining Willie Heron and Ernie Sterne, both international players, on the 1st team.

Antisemitic incidents

Antisemitic incidents reported to the police in the Republic of Ireland:[44]

| Year | Reported incidents |

|---|---|

| 2004 | 2 |

| 2005 | 12 |

| 2006 | 2 |

| 2007 | 2 |

| 2008 | 9 |

| 2009 | 5 |

| 2010 | 13 |

| 2011 | 3 |

| 2012 | 5 |

| 2013 | 2 |

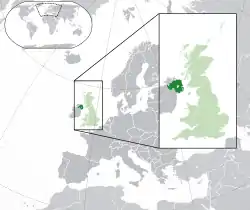

Northern Ireland

The Jews of Northern Ireland have lived primarily in Belfast, where the Belfast Hebrew Congregation, an Ashkenazi Orthodox community, was established in 1870.[45] Former communities were located in Derry and Lurgan.[46][47][48] The first reference to Jews in Belfast dates from 1652, and a "Jew butcher" was mentioned in 1771, suggesting some semblance of a Jewish community at that time.[49]

Belfast rabbinic lineage

The first minister of the congregation was Reverend Joseph Chotzner, who served at the synagogue which was located at Great Victoria Street from 1870–1880 and 1892–1897. Later spiritual leaders at the synagogue included Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog (1916–1919), who later become Chief Rabbi of Israel. His son Chaim Herzog, who became the 6th President of Israel, was born in Belfast. Rabbi John Ross, Rabbi Jacob Schachter and Rabbi Alexander Carlebach followed in this rabbinic lineage.

The Belfast Hebrew Congregation

In the 17th century, Jews reportedly lived in Ulster, the northern province of Ireland, most of which is now in Northern Ireland. A few records also note a Jewish presence during the 18th and early 19th centuries. In the 19th century as the pogroms in Russia and Poland increased, the Belfast Jewish population increased from 52 in the 1861 census, to 78 in 1881 and 273 in 1891.[45][46] There was very little religious conversion but an interesting noble exception was the Countess of Charlemont. The Hon. Elizabeth Jane Somerville, born on 21 June 1834, was the daughter of William Somerville, 1st Baron Athlumney and Lady Maria Harriet Conyngham. She married James Molyneux Caulfeild, 3rd Earl of Charlemont, son of Hon. Henry Caulfeild and Elizabeth Margaret Browne, on 18 December 1856. Her mother-in-law was a favourite in Queen Victoria's court. As a result of her marriage, Hon. Elizabeth Jane Somerville was styled as Countess of Charlemont on 26 December 1863. Soon thereafter she attended synagogue services in Belfast and converted to Judaism. She died on 31 May 1882 aged 47, at Roxborough Castle, Moy, County Tyrone without issue. There were no Jews in Moy, so her initial exposure to Judaism is worthy of research.

Due to the influx of Russian and Polish Jews near the turn of the century, the Jewish community set up a board of guardians in 1893, a Hebrew ladies' foreign benevolent society in 1896, and a Hebrew national school in 1898 to educate their children.[50] For a short time, there was a second Jewish synagogue, the Regent Street Congregation.[51]

Otto Jaffe, Lord Mayor of Belfast, was the life-president of the Belfast Hebrew Congregation and he helped build the city's second synagogue in 1904, paying most of the £4,000 cost. He was a German linen importer who visited Belfast several times a year to buy linen. He prospered and decided to live in Belfast. The synagogue he founded was located at Annesley Street, off Carlisle Circus in the north of the city where most Jews then lived.[52] Subsequently, Barney Hurwitz, a prominent businessman in Belfast, was the president of the congregation for at least two decades. He was also a Justice of the Peace for many years and married Ceina Clein, of the well known Clein family of Cork City. Mrs. Ceina Hurwitz' first cousin Sara Bella Clein also from that well known Cork family. married William Lewis Woolfson of Dublin, a member of a very prominent and numerous Dublin Jewish business family, whose many descendants are today spread all over the world including Ireland and Israel. The Clein family re-unions routinely were attended by up to 3,000 family members and in-laws.

During World War II, a number of Jewish children escaping from the Nazis, via the Kindertransport, reached and were housed in Millisle. The Millisle Refugee Farm (Magill's farm, on the Woburn Road) and was founded by teenage pioneers from the Bachad movement. It took refugees from May 1938 until its closure in 1948.[27]

In 1901 the Jewish population was reported to be 763 people.[46] In 1929, records show that 519 Jews had emigrated from Northern Ireland to the United States.[53] In 1967, the population was estimated at 1,350; by 2004 this number had fallen to 130. It is now estimated to be around 70 to 80. The current membership of the Belfast Hebrew Congregation is believed to be as low as 80.[46]

Gustav Wilhelm Wolff, a partner in Harland and Wolff in Belfast came from a Jewish family that had converted to Protestantism. Harland and Wolff was the largest single shipyard in Britain and Ireland. Edward Harland bought the shipyard for $5,000 from Hickson and Co in 1860/61 with funds from a Liverpool Jewish investor, G.C. Schwabe. Schwabe sent his nephew Gustave Wilhelm Wolff to Belfast to oversee the investment and the company assumed the name Harland and Wolff the following year, 1862. Harland and Wolff built many large ships including the Titanic.

Well known Belfast Jews include: Ronald Appleton QC, Crown Prosecutor during The Troubles in Northern Ireland, who was elected President of the Belfast Hebrew Congregation and served in that post until he retired in 2008; Belfast actors Harold Goldblatt and Harry Towb; pioneer of modern dance in Northern Ireland Helen Lewis; and jazz commentator Solly Lipschitz.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 341 | — |

| 1871 | 230 | −32.6% |

| 1881 | 394 | +71.3% |

| 1891 | 1,506 | +282.2% |

| 1901 | 3,006 | +99.6% |

| 1911 | 3,805 | +26.6% |

| 1926 | 3,686 | −3.1% |

| 1936 | 3,749 | +1.7% |

| 1946 | 3,907 | +4.2% |

| 1961 | 3,255 | −16.7% |

| 1971 | 2,633 | −19.1% |

| 1981 | 2,127 | −19.2% |

| 1991 | 1,581 | −25.7% |

| 2002 | 1,790 | +13.2% |

| 2006 | 1,930 | +7.8% |

| 2011 | 1,984 | +2.8% |

| 2016 | 2,557 | +28.9% |

Source:

| ||

| Year | % Jewish |

|---|---|

| 1891 | 0.04% |

| 1901 | 0.09% |

| 1911 | 0.12% |

| 1926 | 0.12% |

| 1936 | 0.13% |

| 1946 | 0.13% |

| 1961 | 0.12% |

| 1971 | 0.09% |

| 1981 | 0.06% |

| 1991 | 0.04% |

| 2002 | 0.05% |

| 2006 | 0.05% |

| 2011 | 0.04% |

| 2016 | 0.05% |

| Year | % Jewish |

|---|---|

| 1891 | 70.19% |

| 1901 | 72.16% |

| 1911 | 77.92% |

| 1926 | 85.46% |

| 1936 | 89.94% |

| 1946 | 89.86% |

| 1961 | 94.13% |

| 1971 | 93.09% |

| 1981 | 91.77% |

| 1991 | 87.48% |

| 2002 | 68.16% |

| 2006 | 63.01% |

| 2011 | 65.42% |

| 2016 | 56.28% |

According to the 2016 Irish census, Ireland had 2,557 Jews by religion in 2016, of whom 1,439 (56%) lived in its capital, Dublin.[54]

See also

- List of Irish Jews

- Little Jerusalem, Portobello for an account of Little Jerusalem.

- Chief Rabbis of Ireland

- Ireland-Israel relations

- Jews escaping from Nazi Europe to Britain

References

Sources

Citations

- The Annals of Inisfallen, author unknown, translated by Seán Mac Airt 1951

- Frassetto, Michael (2006). Christian attitudes toward the Jews in the Middle Ages. CRC Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0-415-97827-9.

- Gifford, Don; Robert J. Seidman (1989). Ulysses annotated: notes for James Joyce's Ulysses (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-520-06745-5.

- Duffy, Seán; Ailbhe MacShamhráin; James Moynes (2005). Medieval Ireland: an encyclopedia. CRC Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-415-94052-8.

- Cookes Memoirs of Youghal written in 1749 Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Published by the Journal of the Cork Archaeological & Historical Society, 1903 By Robert Day

- "5618 and all that: The Jewish Cemetery Fairview Strand" (PDF). jewishgen.org/. Jewish Gen. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- "Fairview-Marino.com » Fairview & Marino: history 1". 30 July 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012.

- Lurbe, Pierre (1999). "John Toland and the Naturalization of the Jews". Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an Dá Chultúr. Eighteenth-Century Ireland Society. 14: 37–48. JSTOR 30071409.

- Toland, John (1714). Reasons for naturalizing the Jews in Great Britain and Ireland. Printed for J Roberts, London. p. 77.

- LONDON COMMITTEE OF DEPUTIES OF BRITISH JEWS, Jewish Encyclopedia, 1906

- "Jews and Ireland".

- "History : Irish Jewish Community". jewishireland.org.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- Lewis Wormser Harris 1998. Retrieved 5 September 2006.

- "Death notice of Joseph Diamond". Jewish Chronicle. 1 September 1893.

- James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity by Neil R. Davison, p. 37, published by Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0-521-63620-9

- Cheney, David M. "Father John Creagh [Catholic-Hierarchy]". catholic-hierarchy.org.

- Shalom Ireland: a Social History of Jews in Modern Ireland by Ray Rivlin, ISBN 0-7171-3634-5, published by Gill & MacMillan

- Magill Magazine Issue 1, 2008, 46-47

- Jewish envoy says Limerick pogrom is 'over-portrayed', Limerick Leader, Saturday 6 November 2010

- Keogh (1998), p. 26

- Keogh, Dermot; McCarthy, Andrew (2005). Limerick Boycott 1904: Anti-Semitism in Ireland. Mercier Press. pp. xv–xvi.

- Fr. Creagh C.S.S.R. Social Reformer 1870-1947 by Des Ryan, Old Limerick Journal Vol. 41, Winter 2005

- In Search of Ireland's Heroes Carmel McCaffrey

- Ellen Cuffe (Countess of Desart) Oireachtas Members Database

- "In Search of Ireland's Heroes" Carmel McCaffrey

- Lynagh, Catherine (25 November 2005). "Kindertransport to Millisle". Culture Northern Ireland. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- Nolan, Aengus (2008). Joseph Walshe: Irish foreign policy, 1922–1946. Mercier Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-85635-580-3.

- Leeson, David (2002). Irish Volunteers in the Second World War. Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-523-1.

- Wherever Green is Worn, Tim Pat Coogan, 2002, ISBN 0-09-995850-3 page 77 & 86

- Dáil Éireann - Volume 91 - 9 July 1943 Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine – antisemitic speech to the Dáil by Oliver J. Flanagan

- O'Halpin, Eunan (2008). Spying on Ireland. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-925329-6.

- Republic of Ireland Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Stephen Roth Institute

- "Let's do better than the indifference we showed during the Holocaust – Irish Examiner, 20 March 2004

- Keogh (1998) pp. 209–210.

- Department of Justice Memorandum 'Admission of One Hundred Jewish children' 28 April 1948.

- Ireland Archived 21 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Kranzler, David (2004). Holocaust Hero. KTAV Publishing House, Inc. p. 42. ISBN 0-88125-730-3.

The Irish Authority have extended every facility

- The Jews of Ireland by Robert Tracy, published in the Summer 1999 edition of Judaism

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Why the Jews came to Ireland, and left" Sunday Business Post, 18 February 2007 - Reviewed by Emmanual Kehoe

- Irish Rugby Union website - Player History Bethal Solomons Archived 22 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "cricketeurope4.net - This website is for sale! - Resources and Information". cricketeurope4.net. Cite uses generic title (help)

- "Antisemitism Overview of data available in the European Union 2004–2014" (PDF). European Union agency for fundamental rights. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Belfast article, Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901–1906.

- "JCR-UK: Belfast Jewish Community & Synagogues, Northern Ireland, UK". jewishgen.org.

- "Lurgan Hebrew Congregation". JCR-UK. 28 December 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "Londonderry Synagogue, Londonderry". JCR-UK. 27 December 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- "The Jewish Community of Belfast". The Museum of the Jewish People. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus (1902). The Jewish Encyclopedia: Apocrypha-Benash. Funk & Wagnalls. p. 653.

- Belfast's Regent St. Congregation from the JewishGen website

- EJ etc.

- Linfield, H.S. "Statistics of Jews – 1929" in American Jewish Yearbook"

- "Population 1891 to 2016 by County, Religion, CensusYear and Statistic - StatBank - data and statistics". cso.ie.