History of the Church of England

The formal history of the Church of England is traditionally dated by the Church to the Gregorian mission to England by Augustine of Canterbury in AD 597.[1] As a result of Augustine's mission, and based on the tenets of Christianity, Christianity in England fell under control or authority of the Pope. This gave him the power to appoint bishops, preserve or change doctrine, and/or grant exceptions to standard doctrine.

The phrase Church of England, however, frequently refers to the Church as of 1534, when it separated from the Catholic Church and became one of many churches embracing the Protestant Reformation. King Henry VIII of England was less concerned with church doctrine, and more with practical matters. Desiring control over religious dictates in order to annul his marriage with Catherine of Aragon, he had himself (as opposed to the Pope) declared to be the supreme head of the Church in England. This resulted in a schism with the Papacy. Henry also used the schism as an excuse to seize the considerable land and wealth of many monasteries. As a result of this schism, many non-Anglicans consider that the Church of England only existed from the 16th century Protestant Reformation, and the phrase in common usage may frequently mean that. This article, however, includes the entire history of Christian Church in its various forms in England.

Christianity arrived in the British Isles around AD 47 during the Roman Empire according to Gildas's De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae. Archbishop Restitutus and others are known to have attended the Council of Arles in 314. Christianity developed roots in Sub-Roman Britain and later Ireland, Scotland, and Pictland. The Anglo-Saxons (Germanic pagans who progressively seized British territory) during the 5th, 6th and 7th centuries, established a small number of kingdoms and evangelisation of the Anglo-Saxons was carried out by the successors of the Gregorian mission and by Celtic missionaries from Scotland. The church in Wales remained isolated and was only brought within the jurisdiction of English bishops several centuries later.

The Church of England became the established church by an act of Parliament in the Act of Supremacy, beginning a series of events known as the English Reformation.[2] During the reign of Queen Mary I and King Philip, the church was fully restored under Rome in 1555. However, the pope's authority was again explicitly rejected after the accession of Queen Elizabeth I when the Act of Supremacy 1558 was passed. Catholic and Reformed factions vied for determining the doctrines and worship of the church. This ended with the 1558 Elizabethan Settlement, which developed the understanding that the church was to be "both Catholic and Reformed".[3]

Roman and Sub-Roman Christianity in the British Isles

According to medieval traditions, Christianity arrived in Britain in the 1st or 2nd century, although stories involving Joseph of Arimathea, King Lucius, and Fagan are now usually accounted as pious forgeries. The earliest historical evidence of Christianity among the native Britons is found in the writings of such early Christian Fathers as Tertullian and Origen in the first years of the 3rd century, although the first Christian communities probably were established some decades earlier.

Three Romano-British bishops, including Restitutus, metropolitan bishop of London, are known to have been present at the Council of Arles (314). Others attended the Council of Serdica in 347 and that of Ariminum in 360. A number of references to the church in Roman Britain are also found in the writings of 4th century Christian fathers. Britain was the home of Pelagius, who opposed Augustine of Hippo's doctrine of original sin. The first recorded Christian martyr in Britain, St Alban, is thought to have lived in the early 4th century, and his prominence in English hagiography is reflected in the number of parish churches of which he is patron.

Irish Anglicans trace their origins back to the founding saint of Irish Christianity (St Patrick) who is believed to have been a Roman Briton and pre-dated Anglo-Saxon Christianity. Anglicans also consider Celtic Christianity a forerunner of their church, since the re-establishment of Christianity in some areas of Great Britain in the 6th century came via Irish and Scottish missionaries, notably followers of St Patrick and St Columba.[4]

Augustine and the Anglo-Saxon period

Anglicans traditionally date the origins of their Church to the arrival in the Kingdom of Kent of the Gregorian mission to the pagan Anglo-Saxons led by the first Archbishop of Canterbury, Augustine, at the end of the 6th century. Alone among the kingdoms then existing, Kent was Jutish rather than Anglian or Saxon. However, the origin of the Church in the British Isles extends farther back (see above).

Æthelberht of Kent's queen Bertha, daughter of Charibert I, one of the Merovingian kings of the Franks, had brought a chaplain (Liudhard) with her. Bertha had restored a church remaining from Roman times to the east of Canterbury and dedicated it to Martin of Tours, the patronal saint of the Merovingian royal family. This church, Saint Martin's, is the oldest church in England still in use today. Æthelberht himself, though a pagan, allowed his wife to worship God in her own way, at St Martin's. Probably influenced by his wife, Æthelberht asked Pope Gregory I to send missionaries, and in 596 the Pope dispatched Augustine, together with a party of monks.

Augustine had served as praepositus (prior) of the monastery of Saint Andrew in Rome, founded by Gregory. His party lost heart on the way and Augustine went back to Rome from Provence and asked his superiors to abandon the mission project. The pope, however, commanded and encouraged continuation, and Augustine and his followers landed on the Island of Thanet in the spring of 597.

Æthelberht permitted the missionaries to settle and preach in his town of Canterbury, first in Saint Martin's Church and then nearby at what later became St Augustine's Abbey. By the end of the year he himself had been converted, and Augustine received consecration as a bishop at Arles. At Christmas 10,000 of the king's subjects underwent baptism.

Augustine sent a report of his success to Gregory with certain questions concerning his work. In 601 Mellitus, Justus and others brought the pope's replies, with the pallium for Augustine and a present of sacred vessels, vestments, relics, books, and the like. Gregory directed the new archbishop to ordain as soon as possible twelve suffragan bishops and to send a bishop to York, who should also have twelve suffragans. Augustine did not carry out this papal plan, nor did he establish the primatial see at London (in the Kingdom of the East Saxons) as Gregory intended, as the Londoners remained heathen. Augustine did consecrate Mellitus as bishop of London and Justus as bishop of Rochester.

Pope Gregory issued more practicable mandates concerning heathen temples and usages: he desired that temples become consecrated to Christian service and asked Augustine to transform pagan practices, so far as possible, into dedication ceremonies or feasts of martyrs, since "he who would climb to a lofty height must go up by steps, not leaps" (letter of Gregory to Mellitus, in Bede, i, 30).

Augustine re-consecrated and rebuilt an old church at Canterbury as his cathedral and founded a monastery in connection with it. He also restored a church and founded the monastery of St Peter and St Paul outside the walls. He died before completing the monastery, but now lies buried in the Church of St Peter and St Paul.

In 616 Æthelberht of Kent died. The kingdom of Kent and those Anglo-Saxon kingdoms over which Kent had influence relapsed into heathenism for several decades. During the next 50 years Celtic missionaries evangelised the kingdom of Northumbria with an episcopal see at Lindisfarne and missionaries then proceeded to some of the other kingdoms to evangelise those also. Mercia and Sussex were among the last kingdoms to undergo Christianization.

The Synod of Whitby in 664 forms a significant watershed in that King Oswiu of Northumbria decided to follow Roman rather than Celtic practices. The Synod of Whitby established the Roman date for Easter and the Roman style of monastic tonsure in Britain. This meeting of the ecclesiastics with Roman customs and local bishops following Celtic ecclesiastical customs was summoned in 664 at Saint Hilda's double monastery of Streonshalh (Streanæshalch), later called Whitby Abbey. It was presided over by King Oswiu, who did not engage in the debate but made the final ruling.

A later archbishop of Canterbury, the Greek Theodore of Tarsus, also contributed to the organisation of Christianity in England, reforming many aspects of the church's administration.

Medieval consolidation

As in other parts of medieval Europe, tension existed between the local monarch and the Pope about civil judicial authority over clerics, taxes and the wealth of the Church, and appointments of bishops, notably during the reigns of Henry II and John. As begun by Alfred the Great in 871 and consolidated under William the Conqueror in 1066, England became a politically unified entity at an earlier date than other European countries. One of the effects was that the units of government, both of church and state, were comparatively large. England was divided between the Province of Canterbury and the Province of York under two archbishops. At the time of the Norman Conquest, there were only 15 diocesan bishops in England, increased to 17 in the 12th century with the creation of the sees of Ely and Carlisle. This is far fewer than the numbers in France and Italy.[5] A further four medieval dioceses in Wales came within the Province of Canterbury.

Following the depredations of the Viking invasions of the 9th century, most English monasteries had ceased to function and the cathedrals were typically served by small communities of married priests. King Edgar and his Archbishop of Canterbury Dunstan instituted a major reform of cathedrals at a synod at Winchester in 970, where it was agreed that all bishops should seek to establish monasticism in their cathedrals following the Benedictine rule, with the bishop as abbot. Excavations have demonstrated that the reformed monastic cathedrals of Canterbury, Winchester, Sherborne and Worcester were rebuilt on a lavish scale in the late 10th century. However, renewed Viking attacks in the reign of Ethelred, stalled the progress of monastic revival.

In 1072, following the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror and his archbishop Lanfranc sought to complete the programme of reform. Durham and Rochester cathedrals were refounded as Benedictine monasteries, the secular cathedral of Wells was moved to monastic Bath, while the secular cathedral of Lichfield was moved to Chester, and then to monastic Coventry. Norman bishops were seeking to establish an endowment income entirely separate from that of their cathedral body, and this was inherently more difficult in a monastic cathedral, where the bishop was also titular abbot. Hence, following Lanfanc's death in 1090, a number of bishops took advantage of the vacancy to obtain secular constitutions for their cathedrals – Lincoln, Sarum, Chichester, Exeter and Hereford; while the major urban cathedrals of London and York always remained secular. Furthermore, when the bishops' seats were transferred back from Coventry to Lichfield, and from Bath to Wells, these sees reverted to being secular. Bishops of monastic cathedrals, tended to find themselves embroiled in long-running legal disputes with their respective monastic bodies; and increasingly tended to reside elsewhere. The bishops of Ely and Winchester lived in London as did the Archbishop of Canterbury. The bishops of Worcester generally lived in York, while the bishops of Carlisle lived at Melbourne in Derbyshire. Monastic governance of cathedrals continued in England, Scotland and Wales throughout the medieval period; whereas elsewhere in western Europe it was found only at Monreale in Sicily and Downpatrick in Ireland.[6]

An important aspect in the practice of medieval Christianity was the veneration of saints, and the associated pilgrimages to places where the relics of a particular saint were interred and the saint's tradition honoured. The possession of the relics of a popular saint was a source of funds to the individual church as the faithful made donations and benefactions in the hope that they might receive spiritual aid, a blessing or a healing from the presence of the physical remains of the holy person. Among those churches to benefit in particular were: St. Alban's Abbey, which contained the relics of England's first Christian martyr; Ripon, with the shrine of its founder St. Wilfrid; Durham, which was built to house the body of Saints Cuthbert of Lindisfarne and Aidan; Ely, with the shrine of St. Etheldreda; Westminster Abbey, with the magnificent shrine of its founder St. Edward the Confessor; and Chichester, which held the honoured remains of St. Richard. All these saints brought pilgrims to their churches, but among them the most renowned was Thomas Becket, the late Archbishop of Canterbury, who was assassinated by henchmen of King Henry II in 1170. As a place of pilgrimage Canterbury was, in the 13th century, second only to Santiago de Compostela.[7]

Separation from papal authority

John Wycliffe (about 1320 – 31 December 1384) was an English theologian and an early dissident against the Roman Catholic Church during the 14th century. He founded the Lollard movement, which opposed a number of practices of the Church. He was also against papal encroachments on secular power. Wycliffe was associated with statements indicating that the Church in Rome is not the head of all churches, nor did St Peter have any more powers given to him than other disciples. These statements were related to his call for a reformation of its wealth, corruption and abuses. Wycliffe, an Oxford scholar, went so far as to state that "The Gospel by itself is a rule sufficient to rule the life of every Christian person on the earth, without any other rule." The Lollard movement continued with his pronouncements from pulpits even under the persecution that followed with Henry IV up to and including the early years of the reign of Henry VIII.

The first break with Rome (subsequently reversed) came when Pope Clement VII refused, over a period of years, to annul Henry's marriage to Catherine of Aragon, not purely as a matter of principle, but also because the Pope lived in fear of Catherine's nephew, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, as a result of events in the Italian Wars.

Henry first asked for an annulment in 1527. After various failed initiatives he stepped up the pressure on Rome, in the summer of 1529, by compiling a manuscript from ancient sources arguing that, in law, spiritual supremacy rested with the monarch and also against the legality of Papal authority. In 1531 Henry first challenged the Pope when he demanded 100,000 pounds from the clergy in exchange for a royal pardon for what he called their illegal jurisdiction. He also demanded that the clergy should recognise him as their sole protector and supreme head. The church in England recognised Henry VIII as supreme head of the Church of England on 11 February 1531. Nonetheless, he continued to seek a compromise with the Pope, but negotiations (which had started in 1530 and ended in 1532) with the papal legate Antonio Giovanni da Burgio failed. Efforts by Henry to appeal to Jewish scholarship concerning the contours of levirate marriage were unavailing as well.

In May 1532 the Church of England agreed to surrender its legislative independence and canon law to the authority of the monarch. In 1533 the Statute in Restraint of Appeals removed the right of the English clergy and laity to appeal to Rome on matters of matrimony, tithes and oblations. It also gave authority over such matters to the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. This finally allowed Thomas Cranmer, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, to issue Henry's annulment; and upon procuring it, Henry married Anne Boleyn. Pope Clement VII excommunicated Henry VIII in 1533.

In 1534 the Act of Submission of the Clergy removed the right of all appeals to Rome, effectively ending the Pope's influence. The first Act of Supremacy confirmed Henry by statute as the Supreme Head of the Church of England in 1536. (Due to clergy objections the contentious term "Supreme Head" for the monarch later became "Supreme Governor of the Church of England" – which is the title held by the reigning monarch to the present.)

Such constitutional changes made it not only possible for Henry to have his marriage annulled but also gave him access to the considerable wealth that the Church had amassed. Thomas Cromwell, as Vicar General, launched a commission of enquiry into the nature and value of all ecclesiastical property in 1535, which culminated in the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536–1540).

Reformation

Many Roman Catholics consider the separation of the Church in England from Rome in 1534 to be the true origin of the Church of England, rather than dating it from the mission of St. Augustine in AD 597. While Anglicans acknowledge that Henry VIII's repudiation of papal authority caused the Church of England to become a separate entity, they believe that it is in continuity with the pre-Reformation Church of England. Apart from its distinct customs and liturgies (such as the Sarum rite), the organizational machinery of the Church of England was in place by the time of the Synod of Hertford in 672 – 673, when the English bishops were first able to act as one body under the leadership of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Henry's Act in Restraint of Appeals (1533) and the Acts of Supremacy (1534) declared that the English crown was "the only Supreme Head in earth of the Church of England, called Ecclesia Anglicana," in order "to repress and extirpate all errors, heresies, and other enormities and abuses heretofore used in the same." The development of the Thirty-Nine Articles of religion and the passage of the Acts of Uniformity culminated in the Elizabethan Religious Settlement. By the end of the 17th century, the English church described itself as both Catholic and Reformed, with the English monarch as its Supreme Governor.[8] MacCulloch commenting on this situation says that it "has never subsequently dared to define its identity decisively as Protestant or Catholic, and has decided in the end that this is a virtue rather than a handicap."[9]

King Henry VIII of England

The English Reformation was initially driven by the dynastic goals of Henry VIII, who, in his quest for a consort who would bear him a male heir, found it expedient to replace papal authority with the supremacy of the English crown. The early legislation focused primarily on questions of temporal and spiritual supremacy. The Institution of the Christian Man (also called The Bishops' Book) of 1537 was written by a committee of 46 divines and bishops headed by Thomas Cranmer. The purpose of the work, along with the Ten Articles of the previous year, was to implement the reforms of Henry VIII in separating from the Roman Catholic Church and reforming the Ecclesia Anglicana.[note 2] "The work was a noble endeavor on the part of the bishops to promote unity, and to instruct the people in Church doctrine."[11] The introduction of the Great Bible in 1538 brought a vernacular translation of the Scriptures into churches. The Dissolution of the Monasteries and the seizure of their assets by 1540 brought huge amounts of church land and property under the jurisdiction of the Crown, and ultimately into the hands of the English nobility. This simultaneously removed the greatest centres of loyalty to the pope and created vested interests which made a powerful material incentive to support a separate Christian church in England under the rule of the Crown.[12]

Cranmer, Parker and Hooker

By 1549, the process of reforming the ancient national church was fully spurred on by the publication of the first vernacular prayer book, the Book of Common Prayer, and the enforcement of the Acts of Uniformity, establishing English as the language of public worship. The theological justification for Anglican distinctiveness was begun by the Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, the principal author of the first prayer book, and continued by others such as Matthew Parker, Richard Hooker and Lancelot Andrewes. Cranmer had worked as a diplomat in Europe and was aware of the ideas of Reformers such as Andreas Osiander and Friedrich Myconius as well as the Roman Catholic theologian Desiderius Erasmus.

During the short reign of Edward VI, Henry's son, Cranmer and others moved the Church of England significantly towards a more reformed position, which was reflected in the development of the second prayer book (1552) and in the Forty-Two Articles. This reform was reversed abruptly in the reign of Queen Mary, a Roman Catholic who re-established communion with Rome following her accession in 1553.[13]

In the 16th century, religious life was an important part of the cement which held society together and formed an important basis for extending and consolidating political power. Differences in religion were likely to lead to civil unrest at the very least, with treason and foreign invasion acting as real threats. When Queen Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558, a solution was thought to have been found. To minimise bloodshed over religion in her dominions, the religious settlement between the factions of Rome and Geneva was brought about. It was compellingly articulated in the development of the 1559 Book of Common Prayer, the Thirty-Nine Articles, the Ordinal, and the two Books of Homilies. These works, issued under Archbishop Matthew Parker, were to become the basis of all subsequent Anglican doctrine and identity.[8]

The new version of the prayer book was substantially the same as Cranmer's earlier versions. It would become a source of great argument during the 17th century, but later revisions were not of great theological importance.[8] The Thirty-Nine Articles were based on the earlier work of Cranmer, being modelled after the Forty-Two Articles.

The bulk of the population acceded to Elizabeth's religious settlement with varying degrees of enthusiasm or resignation. It was imposed by law, and secured Parliamentary approval only by a narrow vote in which all the Roman Catholic bishops who were not imprisoned voted against. As well as those who continued to recognise papal supremacy, the more militant Protestants, or Puritans as they became known, opposed it. Both groups were punished and disenfranchised in various ways and cracks in the facade of religious unity in England appeared.[13]

| Part of a series on the |

| Reformation |

|---|

|

| Protestantism |

Despite separation from Rome, the Church of England under Henry VIII remained essentially Catholic rather than Protestant in nature. Pope Leo X had earlier awarded to Henry himself the title of fidei defensor (defender of the faith), partly on account of Henry's attack on Lutheranism.[note 3] Some Protestant-influenced changes under Henry included a limited iconoclasm, the abolition of pilgrimages, and pilgrimage shrines, chantries, and the extinction of many saints' days. However, only minor changes in liturgy occurred during Henry's reign, and he carried through the Six Articles of 1539 which reaffirmed the Catholic nature of the church. All this took place, however, at a time of major religious upheaval in Western Europe associated with the Reformation; once the schism had occurred, some reform probably became inevitable. Only under Henry's son Edward VI (reigned 1547 – 1553) did the first major changes in parish activity take place, including translation and thorough revision of the liturgy along more Protestant lines. The resulting Book of Common Prayer, issued in 1549 and revised in 1552, came into use by the authority of the Parliament of England.[13]

Reunion with Rome

Following the death of Edward, his half-sister the Roman Catholic Mary I (reigned 1553 – 1558) came to the throne. She renounced the Henrician and Edwardian changes, first by repealing her brother's reforms then by re-establishing unity with Rome. The Marian Persecutions of Protestants and dissenters took place at this time. The queen's image after the persecutions turned into that of an almost legendary tyrant called Bloody Mary. This view of Bloody Mary was mainly due to the widespread publication of Foxe's Book of Martyrs during her successor Elizabeth I's reign.

Nigel Heard summarises the persecution thus: "It is now estimated that the 274 religious executions carried out during the last three years of Mary's reign exceeded the number recorded in any Catholic country on the continent in the same period."[14]

The Church under Elizabeth I and the Stuarts

Upon Mary's death in 1558, her half-sister Elizabeth I (reigned 1558 – 1603) came to power. Elizabeth became a determined opponent of papal control and once again declared that the Church of England was independent of Papal jurisdiction. In 1559, Parliament recognised Elizabeth as the Church's supreme governor, with a new Act of Supremacy that also repealed the remaining anti-Protestant legislation. A new Book of Common Prayer appeared in the same year. Elizabeth presided over the "Elizabethan Settlement", an attempt to satisfy the Puritan and Catholic forces in England within a single national Church. Elizabeth was eventually excommunicated on 25 February 1570 by Pope Pius V, finally breaking communion between Rome and the Anglican Church.

King James Bible

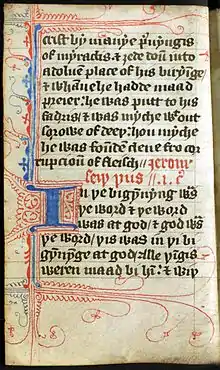

Shortly after coming to the throne, James I attempted to bring unity to the Church of England by instituting a commission consisting of scholars from all views within the Church to produce a unified and new translation of the Bible free of Calvinist and Popish influence. The project was begun in 1604 and completed in 1611 becoming de facto the Authorised Version in the Church of England and later other Anglican churches throughout the communion until the mid-20th century. The New Testament was translated from the Textus Receptus (Received Text) edition of the Greek texts, so called because most extant texts of the time were in agreement with it.[15]

The Old Testament was translated from the Masoretic Hebrew text, while the Apocrypha was translated from the Greek Septuagint (LXX). The work was done by 47 scholars working in six committees, two based in each of the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, and Westminster. They worked on certain parts separately; then the drafts produced by each committee were compared and revised for harmony with each other.

This translation had a profound effect on English literature. The works of most famous authors such as John Milton, Herman Melville, John Dryden and William Wordsworth are deeply inspired by it.[16]

The Authorised Version is often referred to as the King James Version, particularly in the United States. King James was not personally involved in the translation, though his authorisation was legally necessary for the translation to begin, and he set out guidelines for the translation process, such as prohibiting footnotes and ensuring that Anglican positions were recognised on various points. A dedication to James by the translators still appears at the beginning of modern editions.

English Civil War

For the next century, through the reigns of James I and Charles I, and culminating in the English Civil War and the protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, there were significant swings back and forth between two factions: the Puritans (and other radicals) who sought more far-reaching reform, and the more conservative churchmen who aimed to keep closer to traditional beliefs and practices. The failure of political and ecclesiastical authorities to submit to Puritan demands for more extensive reform was one of the causes of open warfare. By continental standards the level of violence over religion was not high, but the casualties included a king, Charles I and an Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. For about a decade (1647–1660), Christmas was another casualty as Parliament abolished all feasts and festivals of the Church to rid England of outward signs of Popishness. Under the Protectorate of the Commonwealth of England from 1649 to 1660, Anglicanism was disestablished, presbyterian ecclesiology was introduced as an adjunct to the Episcopal system, the Articles were replaced with a non-Presbyterian version of the Westminster Confession (1647), and the Book of Common Prayer was replaced by the Directory of Public Worship.

Despite this, about one quarter of English clergy refused to conform. In the midst of the apparent triumph of Calvinism, the 17th century brought forth a Golden Age of Anglicanism.[8] The Caroline Divines, such as Andrewes, Laud, Herbert Thorndike, Jeremy Taylor, John Cosin, Thomas Ken and others rejected Roman claims and refused to adopt the ways and beliefs of the Continental Protestants.[8] The historic episcopate was preserved. Truth was to be found in Scripture and the bishops and archbishops, which were to be bound to the traditions of the first four centuries of the Church's history. The role of reason in theology was affirmed.[8]

Restoration and beyond

With the Restoration of Charles II, Anglicanism too was restored in a form not far removed from the Elizabethan version. One difference was that the ideal of encompassing all the people of England in one religious organisation, taken for granted by the Tudors, had to be abandoned. The 1662 revision of the Book of Common Prayer became the unifying text of the ruptured and repaired Church after the disaster that was the civil war.

When the new king Charles II reached the throne in 1660, he actively appointed his supporters who had resisted Cromwell to vacancies. He translated the leading supporters to the most prestigious and rewarding sees. He also considered the need to reestablish episcopal authority and to reincorporate "moderate dissenters" in order to effect Protestant reconciliation. In some cases turnover was heavy—he made four appointments to the diocese of Worcester in four years 1660–63, moving the first three up to better positions.[17]

Glorious Revolution and Act of Toleration

James II was overthrown by William of Orange in 1688, and the new king moved quickly to ease religious tensions. Many of his supporters had been Nonconformist non-Anglicans. With the Act of Toleration enacted on 24 May 1689, Nonconformists had freedom of worship. That is, those Protestants who dissented from the Church of England such as Baptists, Congregationalists and Quakers were allowed their own places of worship and their own teachers and preachers, subject to acceptance of certain oaths of allegiance. These privileges expressly did not apply to Catholics and Unitarians, and it continued the existing social and political disabilities for dissenters, including exclusion from political office. The religious settlement of 1689 shaped policy down to the 1830s.[18][19] The Church of England was not only dominant in religious affairs, but it blocked outsiders from responsible positions in national and local government, business, professions and academe. In practice, the doctrine of the divine right of kings persisted[20] Old animosities had diminished, and a new spirit of toleration was abroad. Restrictions on Nonconformists were mostly either ignored or slowly lifted. The Protestants, including the Quakers, who worked to overthrow King James II were rewarded. The Toleration Act of 1689 allowed nonconformists who have their own chapels, teachers, and preachers, censorship was relaxed. The religious landscape of England assumed its present form, with an Anglican established church occupying the middle ground, and Roman Catholics and those Puritans who dissented from the establishment, too strong to be suppressed altogether, having to continue their existence outside the national church rather than controlling it.[21]

18th century

Spread of Anglicanism outside England

The history of Anglicanism since the 17th century has been one of greater geographical and cultural expansion and diversity, accompanied by a concomitant diversity of liturgical and theological profession and practice.

At the same time as the English reformation, the Church of Ireland was separated from Rome and adopted articles of faith similar to England's Thirty-Nine Articles. However, unlike England, the Anglican church there was never able to capture the loyalty of the majority of the population (who still adhered to Roman Catholicism). As early as 1582, the Scottish Episcopal Church was inaugurated when James VI of Scotland sought to reintroduce bishops when the Church of Scotland became fully presbyterian (see Scottish reformation). The Scottish Episcopal Church enabled the creation of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America after the American Revolution, by consecrating in Aberdeen the first American bishop, Samuel Seabury, who had been refused consecration by bishops in England, due to his inability to take the oath of allegiance to the English crown prescribed in the Order for the Consecration of Bishops. The polity and ecclesiology of the Scottish and American churches, as well as their daughter churches, thus tends to be distinct from those spawned by the English church—reflected, for example, in their looser conception of provincial government, and their leadership by a presiding bishop or primus rather than by a metropolitan or archbishop. The names of the Scottish and American churches inspire the customary term Episcopalian for an Anglican; the term being used in these and other parts of the world. See also: American Episcopalians, Scottish Episcopalians

At the time of the English Reformation the four (now six) Welsh dioceses were all part of the Province of Canterbury and remained so until 1920 when the Church in Wales was created as a province of the Anglican Communion. The intense interest in the Christian faith which characterised the Welsh in the 18th and 19th centuries was not present in the sixteenth and most Welsh people went along with the church's reformation more because the English government was strong enough to impose its wishes in Wales rather than out of any real conviction.

Anglicanism spread outside of the British Isles by means of emigration as well as missionary effort. The 1609 wreck of the flagship of the Virginia Company, the Sea Venture, resulted in the settlement of Bermuda by that Company. This was made official in 1612, when the town of St George's, now the oldest surviving English settlement in the New World, was established. It is the location of St Peter's Church, the oldest-surviving Anglican church outside the British Isles (Britain and Ireland), and the oldest surviving non-Roman Catholic church in the New World, also established in 1612. It remained part of the Church of England until 1978, when the Anglican Church of Bermuda separated. The Church of England was the state religion in Bermuda and a system of parishes was set up for the religious and political subdivision of the colony (they survive, today, as both civil and religious parishes). Bermuda, like Virginia, tended to the Royalist side during the Civil War. The conflict in Bermuda resulted in the expulsion of Independent Puritans from the island (the Eleutheran Adventurers, who settled Eleuthera, in the Bahamas). The church in Bermuda, before the Civil War, had a somewhat Presbyterian flavour, but mainstream Anglicanism was asserted afterwards (although Bermuda is also home to the oldest Presbyterian church outside the British Isles). Bermudians were required by law in the 17th century to attend Church of England services, and proscriptions similar to those in England existed on other denominations.

English missionary organisations such as USPG—then known as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) were established in the 17th and 18th centuries to bring Anglican Christianity to the British colonies. By the 19th century, such missions were extended to other areas of the world. The liturgical and theological orientations of these missionary organisations were diverse. The SPG, for example, was in the 19th century influenced by the Catholic Revival in the Church of England, while the CMS was influenced by the Evangelicalism of the earlier Evangelical Revival. As a result, the piety, liturgy, and polity of the indigenous churches they established came to reflect these diverse orientations.

19th century and after

The Church of Ireland, an Anglican establishment, was disestablished in Ireland in 1869.[22] The Welsh Church would later be disestablished in 1919, but in England the Church never lost its established role. However Methodism Catholics and other other denominations were relieved of many of their disabilities through the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, Catholic emancipation, and parliamentary reform. The Church responded by greatly enlarging its role of activities, and turning to voluntary contributions for funding.[23]

Revivals

.jpg.webp)

The Plymouth Brethren seceded from the established church in the 1820s. The church in this period was affected by the Evangelical revival and the growth of industrial towns in the Industrial Revolution. There was an expansion of the various Nonconformist churches, notably Methodism. From the 1830s the Oxford Movement became influential and occasioned the revival of Anglo-Catholicism. From 1801 the Church of England and the Church of Ireland were unified and this situation lasted until the disestablishment of the Irish church in 1871 (by the Irish Church Act, 1869).

The growth of the twin "revivals" in 19th century Anglicanism-—Evangelical and Catholic-—was hugely influential. The Evangelical Revival informed important social movements such as the abolition of slavery, child welfare legislation, prohibition of alcohol, the development of public health and public education. It led to the creation of the Church Army, an evangelical and social welfare association and informed piety and liturgy, most notably in the development of Methodism.

The Catholic Revival had a more penetrating impact by transforming the liturgy of the Anglican Church, repositioning the Eucharist as the central act of worship in place of the daily offices, and reintroducing the use of vestments, ceremonial, and acts of piety (such as Eucharistic adoration) that had long been prohibited in the English church and (to a certain extent) in its daughter churches. It influenced Anglican theology, through such Oxford Movement figures as John Henry Newman, Edward Pusey, as well as the Christian socialism of Charles Gore and Frederick Maurice. Much work was done to introduce a more medieval style of church furnishing in many churches. Neo-Gothic in many different forms became the norm rather than the earlier Neo-Classical forms. Both revivals led to considerable missionary efforts in parts of the British Empire.

Expanded roles at home and worldwide

During the 19th century, the Church expanded greatly at home and abroad. The funding came largely from voluntary contributions. In England and Wales it doubled the number of active clergyman, and built or enlarged several thousand churches. Around mid-century it was consecrating seven new or rebuilt churches every month. It proudly took primary responsibility for a rapid expansion of elementary education, with parish-based schools, and diocesan-based colleges to train the necessary teachers. In the 1870s, the national government assume part of the funding; in 1880 the Church was educating 73% of all students. In addition there was a vigorous home mission, with many clergy, scripture readers, visitors, deaconesses and Anglican sisters in the rapidly growing cities.[24] Overseas the Church kept up with the expanding Empire. It sponsored extensive missionary work, supporting 90 new bishoprics and thousands of missionaries across the globe.[25]

In addition to local endowments and pew rentals,[26] Church financing came from a few government grants,[27] and especially from voluntary contributions. The result was that some old rural parishes were well funded, and most of the rapidly growing urban parishes were underfunded.[28]

| Church of England voluntary contributions, 1860–1885 | percent |

|---|---|

| Building restoring and endowing churches | 42% |

| Home missions | 9% |

| Foreign missions | 12% |

| Elementary schools and training colleges | 26% |

| Church institution --literary | 1% |

| Church institution --charitable | 5% |

| Clergy charities | 2% |

| Theological schools | 1% |

| Total | 100% |

| £80,500,000 | |

| Source: Clark 1962.[29] |

Prime ministers and the Queen

Throughout the 19th century patronage continued to play a central role in Church affairs. Tory Prime Ministers appointed most of the bishops before 1830, selecting men who had served the party, or had been college tutors of sponsoring politicians, or were near relations of noblemen. In 1815, 11 bishops came from noble families; 10 had been the tutors of a senior official. Theological achievement or personal piety were not critical factors in their selection. Indeed, the Church was often called the "praying section of the Tory party."[30] Not since Newcastle,[31] over a century before, did a prime minister pay as much attention to church vacancies as William Ewart Gladstone. He annoyed Queen Victoria by making appointments she did not like. He worked to match the skills of candidates to the needs of specific church offices. He supported his party by favouring Liberals who would support his political positions.[32] His counterpart, Disraeli, favoured Conservative bishops to a small extent, but took care to distribute bishoprics so as to balance various church factions. He occasionally sacrificed party advantage to choose a more qualified candidate. On most issues Disraeli and Queen Victoria were close, but they frequently clashed over church nominations because of her aversion to high churchmen.[33]

1914–1970

The current form of military chaplain dates from the era of the First World War. A chaplain provides spiritual and pastoral support for service personnel, including the conduct of religious services at sea or in the field. The Army Chaplains Department was granted the prefix "Royal" in recognition of the chaplains' wartime service. The Chaplain General of the British Army was Bishop John Taylor Smith who held the post from 1901 to 1925.[34]

While the Church of England was historically identified with the upper classes, and with the rural gentry, Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple (1881–1944) was both a prolific theologian and a social activist, preaching Christian socialism and taking an active role in the Labour Party until 1921.[35] He advocated a broad and inclusive membership in the Church of England as a means of continuing and expanding the church's position as the established church. He became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1942, and the same year he published Christianity and Social Order. The best-seller attempted to marry faith and socialism—by "socialism" he meant a deep concern for the poor. The book helped solidify Anglican support for the emerging welfare state. Temple was troubled by the high degree of animosity inside, and between the leading religious groups in Britain. He promoted ecumenicism, working to establish better relationships with the Nonconformists, Jews and Catholics, managing in the process to overcome his anti-Catholic bias.[36][37]

Parliament passed the Enabling Act in 1919 to enable the new Church Assembly, with three houses for bishops, clergy, and laity, to propose legislation for the Church, subject to formal approval of Parliament.[38][39] A crisis suddenly emerged in 1927 over the Church's proposal to revise the classic Book of Common Prayer, which had been in daily use since 1662. The goal was to better incorporate moderate Anglo-Catholicism into the life of the Church. The bishops sought a more tolerant, comprehensive established Church. After internal debate the Church's new Assembly gave its approval. Evangelicals inside the Church, and Nonconformists outside, were outraged because they understood England's religious national identity to be emphatically Protestant and anti-Catholic. They denounced the revisions as a concession to ritualism and tolerance of Roman Catholicism. They mobilized support in parliament, which twice rejected the revisions after intensely heated debates. The Anglican hierarchy compromised in 1929, while strictly prohibiting extreme and Anglo-Catholic practices.[40][41][42]

During the Second World War the head of chaplaincy in the British Army was an Anglican chaplain-general, the Very Revd Charles Symons (with the military rank of major-general), who was formally under the control of the Permanent Under-Secretary of State. An assistant chaplain-general was a chaplain 1st class (full colonel), and a senior chaplain was a chaplain 2nd class (lieutenant colonel).[43] At home the Church saw its role as the moral conscience of the state. It gave enthusiastic support for the war against Nazi Germany. George Bell, Bishop of Chichester and a few clergymen spoke out that the aerial bombing of German cities was immoral. They were grudgingly tolerated. Bishop Bell was chastised by fellow clergy members and passed over for promotion. The Archbishop of York replied, "it is a lesser evil to bomb the war-loving Germans than to sacrifice the lives of our fellow countrymen..., or to delay the delivery of many now held in slavery".[44][45]

A movement towards unification with the Methodist Church in the 1960s failed to pass through all the required stages on the Anglican side, being rejected by the General Synod in 1972. This was initiated by the Methodists and welcomed on the part of the Anglicans but full agreement on all points could not be reached.

Divorce

Standards of morality in Britain changed dramatically after the world wars, in the direction of more personal freedom, especially in sexual matters. The Church tried to hold the line, and was especially concerned to stop the rapid trend toward divorce.[46] It reaffirmed in 1935 that, "in no circumstances can Christian men or women re-marry during the lifetime of a wife or a husband."[47] When king Edward VIII wanted to marry Mrs. Wallis Simpson, a newly divorced woman, in 1936, the archbishop of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang led the opposition, insisting that Edward must go. Lang was later lampooned in Punch for a lack of "Christian charity".[48]

Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin also objected vigorously to the marriage, noting that "although it is true that standards are lower since the war it only leads people to expect a higher standard from their King." Baldwin refused to consider Churchill's concept of a morganatic marriage where Wallis would not become Queen consort and any children they might have would not inherit the throne. After the governments of the Dominions also refused to support the plan, Edward abdicated in order to marry the woman.[49]

When Princess Margaret wanted in 1952 to marry Peter Townsend, a commoner who had been divorced, the Church did not directly intervene but the government warned she had to renounce her claim to the throne and could not be married in church. Randolph Churchill later expressed concern about rumours about a specific conversation between the Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, and the Princess while she was still planning to marry Townsend. In Churchill's view, "the rumour that Fisher had intervened to prevent the Princess from marrying Townsend has done incalculable harm to the Church of England", according to research completed by historian Ann Sumner Holmes. Margaret's official statement, however, specified that the decision had been made "entirely alone", although she was mindful of the Church's teaching on the indissolubility of marriage. Holmes summarizes the situation as, "The image that endured was that of a beautiful young princess kept from the man she loved by an inflexible Church. It was an image and a story that evoked much criticism both of Archbishop Fisher and of the Church' policies regarding remarriage after divorce."[50]

However, when Margaret actually did divorce (Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1st Earl of Snowdon), in 1978, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Donald Coggan, did not attack her, and instead offered support.[51]

In 2005, Prince Charles married Camilla Parker Bowles, a divorcée, in a civil ceremony. Afterwards, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, gave the couple a formal service of blessing.[52] In fact, the arrangements for the wedding and service were strongly supported by the Archbishop "consistent with the Church of England guidelines concerning remarriage"[53] because the bride and groom had recited a "strongly-worded"[54] act of penitence, a confessional prayer written by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury to King Henry VIII.[55] That was interpreted as a confession by the couple of past sins, albeit without specific reference[54] and going "some way towards acknowledging concerns" over their past misdemeanours.[55]

1970–present

The Church Assembly was replaced by the General Synod in 1970.

On 12 March 1994 the Church of England ordained its first female priests. On 11 July 2005 a vote was passed by the Church of England's General Synod in York to allow women's ordination as bishops. Both of these events were subject to opposition from some within the church who found difficulties in accepting them. Adjustments had to be made in the diocesan structure to accommodate those parishes unwilling to accept the ministry of women priests. (See women's ordination)

The first black archbishop of the Church of England, John Sentamu, formerly of Uganda, was enthroned on 30 November 2005 as Archbishop of York.

In 2006 the Church of England at its General Synod made a public apology for the institutional role it played as a historic owner of slave plantations in Barbados and Barbuda. The Reverend Simon Bessant recounted the history of the church on the island of Barbados, West Indies, where through a charitable bequest received in 1710 by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, thousands of sugar plantation slaves had been appallingly treated and branded using red-hot irons as the property of the "society".[56]

In 2010, for the first time in the history of the Church of England, more women than men were ordained as priests (290 women and 273 men).[57]

See also

Notes

- The Chair of St Augustine is the seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury and in his role as head of the Anglican Communion. Archbishops of Canterbury are enthroned twice: firstly as diocesan Ordinary (and Metropolitan and Primate of the Church of England) in the archbishop's throne, by the Archdeacon of Canterbury; and secondly as leader of the worldwide church in the Chair of St Augustine by the senior (by length of service) Archbishop of the Anglican Communion. The stone chair is therefore of symbolic significance throughout Anglicanism.

- Ecclesia anglicana is a Medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 meaning the "English Church".[10]

- He wrote Assertio septem sacramentorum in response to Luther's ideas on the sacraments.

References

- Delaney, John P. (1980). Dictionary of Saints (Second ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-385-13594-8.

- The English Reformation by Professor Andrew Pettegree. Bbc.co.uk.

- "Canons of the Church of England" (PDF). Church of England. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Gonzalez 1984.

- Clifton-Taylor 1967.

- Robert N. Swanson, Church and society in late medieval England (Blackwell, 1993).

- John Munns, Cross and Culture in Anglo-Norman England: Theology, Imagery, Devotion (Boydell & Brewer, 2016).

- Cross & Livingstone 1997, p. 65.

- MacCulloch 1990, p. 172.

- "Anglicanism". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Blunt, J. (1869). The Reformation of the Church of England – its history, principles and results (A.D. 1514–1547). London, Oxford, and Cambridge: Rivingtons. pp. 444–445.

- A.G. Dickens, The English Reformation (2nd ed. 1989).

- Dickens, The English Reformation (2nd ed. 1989).

- Heard 2000, p. 96.

- Alister E. McGrath, In the beginning: the story of the King James Bible and how it changed a nation, a language and a culture (2002).

- David L. Jeffrey, A dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature (1992).

- R. A. Beddard, "A Reward for Services Rendered: Charles II and the Restoration Bishopric of Worcester, 1660–1663." Midland History 29.1 (2004): 61–91.

- Julian Hoppit, A land of liberty? England 1689–1727 (Oxford UP, 2002 pp 30–39.

- Sheridan Gilley and William J. Sheils, eds. A history of religion in Britain: practice and belief from pre-Roman times to the present. (1994), 168–274.

- J.C.D. Clark, English Society 1688–1832: ideology, social structure and political practice in the ancien regime (1985), pp 119–198

- George Clark, Later Stuarts: 1616–1714 (2nd ed. 1956) pp 153–60.

- Christopher F. McCormack, "The Irish Church Disestablishment Act (1869) and the general synod of the Church of Ireland (1871): the art and structure of educational reform." History of Education 47.3 (2018): 303-320.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966) and The Victorian Church, Part Two: 1860–1901 (1970).

- Sarah Flew , Philanthropy and the Funding of the Church of England: 1856–1914 (2015) excerpt

- Michael Gladwin, Anglican Clergy in Australia, 1788–1850: Building a British World (2015).

- J.C. Bennett, "The Demise and—Eventual—Death of Formal Anglican Pew-Renting in England." Church History and Religious Culture 98.3-4 (2018): 407-424.

- Sarah Flew, "The state as landowner: neglected evidence of state funding of Anglican Church extension in London in the latter nineteenth century." Journal of Church and State 60.2 (2018): 299-317 online.

- G. Kitson Clark, The making of Victorian England (1962) pp. 167–173.

- G. Kitson Clark, The making of Victorian England (1962) page 170.

- D. C Somervell, English thought in the nineteenth century (1929) p. 16

- Donald G. Barnes, "The Duke of Newcastle, Ecclesiastical Minister, 1724–54," Pacific Historical Review 3#2 pp. 164–191

- William Gibson, "'A Great Excitement' Gladstone and Church Patronage 1860–1894." Anglican and Episcopal History 68#3 (1999): 372–396. in JSTOR

- William T. Gibson, "Disraeli's Church Patronage: 1868–1880." Anglican and Episcopal History 61#2 (1992): 197–210. in JSTOR

- Snape 2008, p. vi.

- Adrian Hastings, "Temple, William (1881–1944)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/36454

- Dianne Kirby, "Christian co-operation and the ecumenical ideal in the 1930s and 1940s." European Review of History 8.1 (2001): 37–60.

- F. A. Iremonger, William Temple, Archbishop of Canterbury: His Life and Letters (1948) pp 387–425. online

- Colin Buchanan (2015). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. p. 229. ISBN 9781442250161.

- Roger Lloyd, The Church of England in the 20th Century (1950)) 2:5-18.

- G. I. T. Machin, "Parliament, the Church of England, and the Prayer Book Crisis, 1927–8." Parliamentary History 19.1 (2000): 131–147.

- John Maiden, National Religion and the Prayer Book Controversy, 1927–1928 (2009).

- John G. Maiden, "English Evangelicals, Protestant National Identity, and Anglican Prayer Book Revision, 1927–1928." Journal of Religious History 34#4 (2010): 430–445.

- Brumwell, P. Middleton (1943) The Army Chaplain: the Royal Army Chaplains' Department; the duties of chaplains and morale. London: Adam & Charles Black

- Chris Brown (2014). International Society, Global Polity: An Introduction to International Political Theory. p. 47. ISBN 9781473911284.

- Andrew Chandler, "The Church of England and the obliteration bombing of Germany in the Second World War." English Historical Review 108#429 (1993): 920-946.

- G. I. T. Machin, "Marriage and the Churches in the 1930s: Royal abdication and divorce reform, 1936–7." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 42#1 (1991): 68–81.

- Ann Sumner Holmes (2016). The Church of England and Divorce in the Twentieth Century: Legalism and Grace. Taylor & Francis. p. 44. ISBN 9781315408491.

- Tony Ditcham (15 August 2013). A Home on the Rolling Main: A Naval Memoir 1940–1946. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9780415669832. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Pearce and Goodland (2 September 2013). British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown. Routledge. p. 80. ISBN 9780415669832.

- Ann Sumner Holmes (13 October 2016). The Church of England and Divorce in the Twentieth Century: Legalism and Grace. Routledge. pp. 43–48, 74–80, quotes pp 44, 45, 79. ISBN 9781848936171.

- Ben Pimlott, The Queen: A Biography of Elizabeth II. (1998), p 443.

- "Divorce and the church: how Charles married Camilla". The Times. 28 November 2017.

- Williams, Rowan (10 February 2005). "Statement of support". Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "Charles and Camilla to confess past sins". Fox News. 9 April 2005. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Brown, Jonathan (7 April 2005). "Charles and Camilla to repent their sins". The Independent.

- "Church apologises for slave trade". BBC. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 8 February 2006.

- "More new women priests than men for first time". The Daily Telegraph. 4 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

Further reading

- Buchanan, Colin. Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism (2nd ed. 2015) excerpt

- Chadwick, Owen. The Victorian Church, Part One: 1829–1859 (1966); The Victorian Church, Part Two: 1860–1901 (1970)

- Clifton-Taylor, Alec (1967). The Cathedrals of England. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-20062-9.

- Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A, eds. (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Flew, Sarah. Philanthropy and the Funding of the Church of England: 1856–1914 (2015) excerpt

- Gonzalez, Justo L. (1984). The Early Church to the Dawn of the Reformation. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-063315-8.

- Hardwick, Joseph. An Anglican British world: The Church of England and the expansion of the settler empire, c. 1790–1860 (Manchester UP, 2014).

- Hastings, Adrian. A History of English Christianity 1920–2000 (4th ed. 2001), 704pp, a standard scholarly history.

- Heard, Nigel (2000). Edward VI and Mary: A Mid-Tudor Crisis?. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-74317-1.

- Hunt, William (1899). The English Church from Its Foundation to the Norman Conquest (597-1066). Vol I. Macmillan & Company.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid (1990). The Later Reformation in England, 1547–1603. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-92139-5.

- Kirby, James. Historians and the Church of England: Religion and Historical Scholarship, 1870–1920 (2016) online at DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198768159.001.0001

- Lawson, Tom. God and War: The Church of England and Armed Conflict in the Twentieth Century (Routledge, 2016).

- Maughan Steven S. Mighty England Do Good: Culture, Faith, Empire, and World in the Foreign Missions of the Church of England, 1850–1915 (2014).

- Norman, Edward R. Church and society in England 1770–1970: a historical study (Oxford UP, 1976).

- Picton, Hervé. A Short History of the Church of England: From the Reformation to the Present Day. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. 180 p.

- Sampson, Anthony. Anatomy of Britain (1962) online free pp 160–73. Sampson had five later updates, but they all left religion out.

- Snape, Michael Francis (2008). The Royal Army Chaplains' Department, 1796–1953: Clergy Under Fire. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-346-8.

- Soloway, Richard Allen. “Church and Society: Recent Trends in Nineteenth Century Religious History.” Journal of British Studies 11.2 1972, pp. 142–159. online

- Tapsell, Grant. The later Stuart Church, 1660–1714 (2012).

- Walsh, John; Haydon, Colin; Taylor, Stephen (1993). The Church of England C.1689-c.1833: From Toleration to Tractarianism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41732-7.