History of purgatory

The idea of purgatory has roots that date back into antiquity. A sort of proto-purgatory called the "celestial Hades" appears in the writings of Plato and Heraclides Ponticus and in many other pagan writers. This concept is distinguished from the Hades of the underworld described in the works of Homer and Hesiod. In contrast, the celestial Hades was understood as an intermediary place where souls spent an undetermined time after death before either moving on to a higher level of existence or being reincarnated back on earth. Its exact location varied from author to author. Heraclides of Pontus thought it was in the Milky Way; the Academicians, the Stoics, Cicero, Virgil, Plutarch, the Hermetical writings situated it between the Moon and the Earth or around the Moon; while Numenius and the Latin Neoplatonists thought it was located between the sphere of the fixed stars and the Earth.[1]

Perhaps under the influence of Hellenistic thought, the intermediate state entered Jewish religious thought in the last centuries B.C.E.. In Maccabees we find the practice of prayer for the dead with a view to their after life purification[2] a practice accepted by some Christians. The same practice appears in other traditions, such as the medieval Chinese Buddhist practice of making offerings on behalf of the dead, who are said to suffer numerous trials.[3] Among other reasons, Catholic teaching of purgatory is based on the pre-Christian (Judaic) practice of prayers for the dead.[4]

Descriptions and doctrine regarding purgatory developed over the centuries.[5] Roman Catholic Christians who believe in purgatory interpret passages such as 2 Maccabees 12:41–46, 2 Timothy 1:18, Matthew 12:32, Luke 16:19–16:26, Luke 23:43, 1 Corinthians 3:11–3:15 and Hebrews 12:29 as support for prayer for purgatorial souls who are believed to be within an active interim state for the dead undergoing purifying flames (which could be interpreted as an analogy or allegory) after death until purification allows admittance into heaven.[3] The first Christians did not develop consistent and universal beliefs about the interim state.[6] Gradually, Christians, especially in the West,[6] took an interest in circumstances of the interim state between one's death and the future resurrection. Christians both East and West prayed for the dead in this interim state, although theologians in the East refrained from defining it as a physical location with a distinct name.[6] Augustine of Hippo distinguished between the purifying fire that saves and eternal consuming fire for the unrepentant.[3] Gregory the Great established a connection between earthly penance and purification after death. All Soul's Day, established in the 10th century, turned popular attention to the condition of departed souls.[3]

The idea of Purgatory as a physical place (like heaven and hell) became Roman Catholic teaching in the late 11th century.[7] Medieval theologians concluded that the purgatorial punishments consisted of material fire. The Western formulation of purgatory proved to be a sticking point in the Great Schism between East and West. The Roman Catholic Church believes that the living can help those whose purification from their sins is not yet completed not only by praying for them but also by gaining indulgences for them[8] as an act of intercession.[9] The later Middle Ages saw the growth of considerable abuses, such as the unrestricted sale of indulgences by professional "pardoners"[9] sent to collect contributions to projects such as the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. These abuses were one of the factors that led to the Protestant Reformation. Most Protestant religions rejected the idea of purgatory as it conflicted with Protestant theology of "Salvation by grace alone". Luther's canon of the Bible excluded the Deuterocanonical books. Modern Catholic theologians have softened the punitive aspects of purgatory and stress instead the willingness of the dead to undergo purification as preparation for the happiness of heaven[3]

The English Anglican scholar John Henry Newman argued, in a book that he wrote before becoming Catholic, that the essence of the doctrine on purgatory is locatable in ancient tradition, and that the core consistency of such beliefs are evidence that Christianity was "originally given to us from heaven".[10]

Christian Antiquity

Prayer for the dead

Prayers for the dead were known to ancient Jewish practice, and it has been speculated that Christianity may have taken its similar practice from its Jewish heritage.[12] In Christianity, prayer for the dead is attested since at least the 2nd century,[13] evidenced in part by the tomb inscription of Abercius, Bishop of Hierapolis in Phrygia (d. c. 200).[14] Celebration of the Eucharist for the dead is attested to since at least the 3rd century.[15]

Purification after death

Specific examples of belief in purification after death and of the communion of the living with the dead through prayer are found in many of the Church Fathers.[16] Irenaeus (c. 130-202) mentioned an abode where the souls of the dead remained until the universal judgment, a process that has been described as one which "contains the concept of... purgatory."[17] Both St. Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215) and his pupil, Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254), developed a view of purification after death;[18] this view drew upon the notion that fire is a divine instrument from the Old Testament, and understood this in the context of New Testament teachings such as baptism by fire, from the Gospels, and a purificatory trial after death, from St. Paul.[19] Origen, in arguing against soul sleep, stated that the souls of the elect immediately entered paradise unless not yet purified, in which case they passed into a state of punishment, a penal fire, which is to be conceived as a place of purification.[20] For both Clement and Origen, the fire was neither a material thing nor a metaphor, but a "spiritual fire".[21] An early Latin author, Tertullian (c. 160-225), also articulated a view of purification after death.[22] In Tertullian's understanding of the afterlife, the souls of martyrs entered directly into eternal blessedness,[23] whereas the rest entered a generic realm of the dead. There the wicked suffered a foretaste of their eternal punishments,[23] whilst the good experienced various stages and places of bliss wherein "the idea of a kind of purgatory… is quite plainly found," an idea that is representative of a view widely dispersed in antiquity.[24] Later examples, wherein further elaborations are articulated, include St. Cyprian (d. 258),[25] St. John Chrysostom (c. 347-407),[26] and St. Augustine (354-430),[27] among others.

Interim state

The Christian notion of an interim state of souls after death developed only gradually. This may be in part because it was of little interest as long as Christians looked for an imminent end of the world, as many scholars believe they did. The Eastern Church came to admit the existence of an intermediate state, but refrained from defining it, while at the same time maintaining the belief in prayer for the dead that was a constant feature of both Eastern and Western liturgies, and which is unintelligible without belief in an interim state in which the dead may be benefited. Christians in the West demonstrated much more curiosity about this interim state than those in the East: The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity and occasional remarks by Saint Augustine give expression to their belief that sins can be purged by suffering in an afterlife and that the process can be accelerated by prayer.[6]

In the early 5th century, Augustine spoke of the pain that purgatorial fire causes as more severe than anything a man can suffer in this life.[28] And Gregory the Great said that those who after this life "will expiate their faults by purgatorial flames," and he adds "that the pain be more intolerable than any one can suffer in this life."[29]

Early Middle Ages

During the Early Middle Ages, the doctrine of final purification developed distinctive features in the Latin-speaking West – these differed from developments in the Greek-speaking East.

Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory the Great's Dialogues, written in the late 6th century, evidence a development in the understanding of the afterlife distinctive of the direction that Latin Christendom would take:

As for certain lesser faults, we must believe that, before the Final Judgment, there is a purifying fire. He who is truth says that whoever utters blasphemy against the Holy Spirit will be pardoned neither in this age nor in the age to come. From this sentence we understand that certain offenses can be forgiven in this age, but certain others in the age to come.[31]

Visions of purgatory

Visions of purgatory abounded; Bede (died 735) mentioned a vision of a beautiful heaven and a lurid hell with adjacent temporary abodes,[32] as did Saint Boniface (died 754).[33] In the 7th century, the Irish abbot St. Fursa described his foretaste of the afterlife, where, though protected by angels, he was pursued by demons who said: "It is not fitting that he should enjoy the blessed life unscathed..., for every transgression that is not purged on earth must be avenged in heaven", and on his return he was engulfed in a billowing fire that threatened to burn him, "for it stretches out each one according to their merits... For just as the body burns through unlawful desire, so the soul will burn, as the lawful, due penalty for every sin."[34]

Other influential writers

Others who expounded upon purgatory include Haymo (died 853), Rabanus Maurus (c. 780 – 856), and Walafrid Strabo (c. 808 – 849).[35]

High Middle Ages

East-West Schism

In 1054, the Bishop of Rome and the four Greek-speaking patriarchs of the East excommunicated each other, triggering the East-West Schism. The schism split the church basically into the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. In the West, the understanding of purification through fire in the intermediate state continued to develop.

All Soul's Day

The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates several All Souls' Days in the year,[36] but in the West only one such annual commemoration is celebrated. The establishment, at the end of the 10th century, of this remembrance helped focus popular imagination on the fate of the departed, and fostered a sense of solidarity between the living and the dead. Then, in the 12th century, the elaboration of the theology of penance helped create a notion of purgatory as a place to complete penances unfinished in this life.[6]

Twelfth century

By the 12th century, the process of purification had acquired the Latin name, "purgatorium", from the verb purgare: to purge.[37]

"Birth of purgatory"

Medievalist Jacques Le Goff defines the "birth of purgatory", i.e. the conception of purgatory as a physical place, rather than merely as a state, as occurring between 1170 and 1200.[38] Le Goff acknowledged that the notion of purification after death, without the medieval notion of a physical place, existed in antiquity, arguing specifically that Clement of Alexandria, and his pupil Origen of Alexandria, derived their view from a combination of biblical teachings, though he considered vague concepts of purifying and punishing fire to predate Christianity.[39] Le Goff also considered Peter the Lombard (d. 1160), in expounding on the teachings of St. Augustine and Gregory the Great, to have contributed significantly to the birth of purgatory in the sense of a physical place.

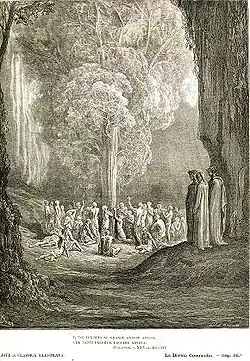

While the idea of purgatory as a process of cleansing thus dated back to early Christianity, the 12th century was the heyday of medieval otherworld-journey narratives such as the Irish Visio Tnugdali, and of pilgrims' tales about St. Patrick's Purgatory, a cavelike entrance to purgatory on a remote island in Ireland.[40] The legend of St Patrick's Purgatory (Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii) written in that century by Hugh of Saltry, also known as Henry of Sawtry, was "part of a huge, repetitive contemporary genre of literature of which the most familiar today is Dante's";[41] another is the Visio Tnugdali. Other legends localized the entrance to Purgatory in places such as a cave on the volcanic Mount Etna in Sicily.[42] Thus the idea of purgatory as a physical place became widespread on a popular level, and was defended also by some theologians.

Thomas Aquinas

What has been called the classic formulation of the doctrine of purgatory, namely the means by which any unforgiven guilt of venial sins is expiated and punishment for any kind of sins is borne, is attributed to Thomas Aquinas[6] although he ceased work on his Summa Theologica before reaching the part in which he would have dealt with Purgatory, which is treated in the "Supplement" added after his death. According to Aquinas and the other scholastics, the dead in purgatory are at peace because they are sure of salvation, and may be helped by the prayers of the faithful and especially the offering of the Eucharist, because they are still part of the Communion of Saints, from which only those in hell or limbo are excluded.[6]

Second Council of Lyon

At the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, the Catholic Church defined, for the first time, its teaching on purgatory, in two points:

- some souls are purified after death;

- such souls benefit from the prayers and pious duties that the living do for them.

The council declared:

[I]f they die truly repentant in charity before they have made satisfaction by worthy fruits of penance for (sins) committed and omitted, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorical or purifying punishments, as Brother John has explained to us. And to relieve punishments of this kind, the offerings of the living faithful are of advantage to these, namely, the sacrifices of Masses, prayers, alms, and other duties of piety, which have customarily been performed by the faithful for the other faithful according to the regulations of the Church.[43]

Late Middle Ages

Through theology, literature, and indulgences, purgatory became central to late medieval religion[6] and became associated with indulgences and other penitential practices, such as fasting. This was another step in the development of this doctrine.

See also: Anima sola, Gertrude the Great, Sabbatine privilege

Subsequent history

Latin-Greek relations

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds that "there is a state beyond death where believers continue to be perfected and led to full divinization".[44] But in the 15th century, at the Council of Florence, authorities of the Eastern Orthodox Church identified some aspects of the Latin idea of purgatory as a point on which there were principal differences between Greek and Latin doctrine.[45] The Eastern Christians objected especially to the legalistic distinction between guilt and punishment[6] and to the fire of purgatory being material fire. The decrees of the Council, which contained no reference to fire and, without using the word "purgatory" ("purgatorium"), spoke only of "pains of cleansing" ("poenis purgatoriis"),[46] were rejected at the time by the Eastern churches but formed the basis on which certain Eastern communities were later received into full communion with the Roman Catholic Church.[47] At the Council itself, the Greek Metropolitan Bessarion argued against the existence of real purgatorial fire. In effecting full communion between the Roman Catholic Church and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church by the Union of Brest (1595), the two agreed, "We shall not debate about purgatory, but we entrust ourselves to the teaching of the Holy Church."[48] Furthermore, the Council of Trent, in its discussion of purgatory, instructed the bishops not to preach on such "difficult and subtle questions".[49]

Protestant Reformation

During the Protestant Reformation, certain Protestant theologians developed a view of salvation (soteriology) that excluded purgatory. This was in part a result from a doctrinal change concerning justification and sanctification on the part of the reformers. In Catholic theology, one is made righteous by a progressive infusion of divine grace accepted through faith and cooperated with through good works; however, in Martin Luther's doctrine, justification rather meant "the declaring of one to be righteous", where God imputes the merits of Christ upon one who remains without inherent merit.[50] In this process, good works done in faith (i.e. through penance) are more of an unessential byproduct that contribute nothing to one's own state of righteousness; hence, in Protestant theology, "becoming perfect" came to be understood as an instantaneous act of God and not a process or journey of purification that continues in the afterlife.

Thus, Protestant soteriology developed the view that each one of the elect (saved) experienced instantaneous glorification upon death. As such, there was little reason to pray for the dead. Luther wrote in Question No. 211 in his expanded Small Catechism: "We should pray for ourselves and for all other people, even for our enemies, but not for the souls of the dead." Luther, after he stopped believing in purgatory around 1530,[51] openly affirmed the doctrine of soul sleep.[52] Purgatory came to be seen as one of the "unbiblical corruptions" that had entered Church teachings sometime subsequent to the apostolic age. Hence, the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England produced during the English Reformation stated: "The Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory...is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture; but rather repugnant to the word of God" (article 22). Likewise, John Calvin, central theologian of Reformed Protestantism, considered purgatory a superstition, writing in his Institutes (5.10): "The doctrine of purgatory ancient, but refuted by a more ancient Apostle. Not supported by ancient writers, by Scripture, or solid argument. Introduced by custom and a zeal not duly regulated by the word of God… we must hold by the word of God, which rejects this fiction." In general, this position remains indicative of Protestant belief today, with the notable exception of certain Anglo-Catholics, such as the Guild of All Souls, which describe themselves as Reformed and Catholic (and specifically not Protestant) and believe in purgatory.

In response to Protestant Reformation critics, the Council of Trent reaffirmed purgatory as already taught by the Second Council of Lyon, confining itself to the concepts of purification after death and the efficacy of prayers for the dead.[6] It simply affirmed the existence of purgatory and the great value of praying for the deceased, but sternly instructed preachers not to push beyond that and distract, confuse, and mislead the faithful with unnecessary speculations concerning the nature and duration of purgatorial punishments.[53] It thus forbade presentation as Church teaching of the elaborate medieval speculation that had grown up around the concept of purgatory.

Anglican apologist C. S. Lewis gave as an example of this speculation, which he interpreted as what the Church of England's Thirty-Nine Articles, XXII meant by "the Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory",[54] the depiction of the state of purgatory as just a temporary hell with horrible devils tormenting souls. The etymology of the word "purgatory", he remarked, indicates cleansing, not simply retributive punishment. Lewis declared his personal belief in purgatory, a process of after-death purification.[55]

Later speculations include the idea advocated by Saints Robert Bellarmine and Alphonsus Liguori of asking for the prayers of the souls in purgatory,[6] a notion not accepted by all theologians. Saint Francis de Sales argued that, in the mention in Philippians 2:10 of every knee bowing at the name of Jesus "in heaven, on earth, and under the earth", "under the earth" was a reference to those in purgatory, since it could not apply to those in hell.[56] Frederick William Faber said that there have been private revelations of souls who "abide their purification in the air, or by their graves, or near altars where the Blessed Sacrament is, or in the rooms of those who pray for them, or amid the scenes of their former vanity and frivolity".[57][58]

References

- Adrian Mihai,"L'Hadès céleste. Histoire du purgatoire dans l'Antiquité"(Garnier: 2015), pp.185-188

- cf. 2 Maccabees 12:42–44

- Purgatory in Encyclopædia Britannica

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1032

- Isabel Moreira, Heaven's Purge (Oxford University Press, 2010) pp. 3-13

- Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Purgatory

- Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984)

- CCC, 1479 Archived 6 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Cross, F. L., ed., The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005), article indulgences

- John Henry Newman, An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, chapter 2, section 3, paragraph 2.

- Cabrol and Leclercq, Monumenta Ecclesiæ Liturgica. Volume I: Reliquiæ Liturgicæ Vetustissimæ (Paris, 1900-2) pp. ci-cvi, cxxxix.

- George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106; cf. Pastor I, iii. 7, also Ambrose, De Excessu fratris Satyri 80

- Gerald O' Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 217

- Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 106

- Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27.

- Christian Dogmatics vol. 2 (Philadelphia : Fortress Press, 1984) p. 503; cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies 5.31.2, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers eds. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979) 1:560 cf. 5.36.2 / 1:567; cf. George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 107

- Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 337; Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 6:14

- Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) p. 53; cf. Leviticus 10:1–2, Deuteronomy 32:22, 1Corinthians 3:10–15

- Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 377. read online.

- Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 55-57; cf. Clement of Alexandria, Stromata 7:6 and 5:14

- Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27; cf. Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London, Williams & Norgate, 1995) p. 296 n. 1; George Cross, "The Differentiation of the Roman and Greek Catholic Views of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912); Tertullian De Anima

- A. J. Visser, "A Bird's-Eye View of Ancient Christian Eschatology", in Numen (1967) p. 13

- Adolph Harnack, History of Dogma vol. 2, trans. Neil Buchanan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1905) p. 296 n. 1. read online; cf. Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 58-59

- Cyprian, Letters 51:20; Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27

- John Chrysostom, Homily on First Corinthians 41:5; Homily on Philippians 3:9-10; Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27

- Augustine, Sermons 159:1, 172:2; City of God 21:13; Handbook on Faith, Hope, and Charity 18:69, 29:109; Confessions 2.27; Gerald O' Collins and Mario Farrugia, Catholicism: the story of Catholic Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) p. 36; Gerald O'Collins and Edward G. Farrugia, A Concise Dictionary of Theology (Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 2000) p. 27

- "gravior erit ignis quam quidquid potest homo pati in hac vita" (P. L., col. 397), quoted in Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory.

- Ps. 3 poenit., n. 1, quoted in Catholic Encyclopedia: Purgatory

- Vita Gregorii, ed. B. Colgrave, chapter 26 (see also Colgrave's introduction p. 51); John the Deacon, Life of Saint Gregory, IV, 70.

- Gregory the Great, Dialogues 4, 39: PL 77, 396; cf. Matthew 12:31

- George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192; cf. Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica 4.19

- George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192; cf. Epistula ad Eadburgham 20

- Brown, Rise of Western Christendom (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003) p. 259; cf. Vision of Fursa 8.16, 16.5

- George Cross, "The Medieval Catholic Doctrine of the Future Life", in The Biblical World (1912) p. 192

- See the Wikipedia article for a list.

- See C. S. Watkins, "Sin, penance and purgatory in the Anglo-Norman realm: the evidence of visions and ghost stories", in Past and Present 175 (May 2002) pp. 3-33.

- Jacques Le Goff, La naissance du purgatoire. (Bibliothèque des Histoires) Paris: Gallimard, 1981; an English translation is available under the title The Birth of Purgatory, published by the University of Chicago Press (the English is referenced here).

- Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (University of Chicago Press, 1984) pp. 55-57.

- Online Encyclopædia Britannica

- Lough Derg: the spirit of a holy place Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine; cf. Visions of the Other World in Middle English by Robert Easting, p. 16; The legend of the "Purgatory of Saint Patrick": from Ireland, until Dante and beyond.

- A History of the Church in the Middle Ages by F. Donald Logan

- Denzinger 856; original text in Latin: [http://catho.org/9.php?d=bxx#bqn "Quod si vere paenitentes ..."

- Ted A. Campbell, Christian Confessions: a Historical Introduction (Westminster John Knox Press 1996 ISBN 0-664-25650-3), p. 54

- The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 201; cf. Orthodoxinfo.com, The Orthodox Response to the Latin Doctrine of Purgatory

- Denzinger, 1304

- The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999) p. 202

- Union of Brest (1595) Article 5

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1913), entry on Purgatory; cf. Council of Trent, Session XXV, "De Purgatorio"

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 119

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) p. 580; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead pp. 34-39

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, The Reformation: A History (New York: Penguin Books, 2004) pp. 580-581; cf. Koslofsky, Reformation of the Dead p. 48

- Decree on Purgatory (1563)

- "Articles of Religion". Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Lewis, C.S. (Cllive Staples) (2002). Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 108. ISBN 9780547541396. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Francis de Sales. "The Doctrine of Purgatory, chapter VII". Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Faber, Frederick William (1854). All for Jesus: or, The Easy Ways of Divine Love (40th American ed.). Baltimore and New York: John Murphy. p. 393. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- Meynell (compiler), Wilfrid (1914). The Spirit of Father Faber, Apostle of London. New York, Cincinnati, Chicago: Benziger Brothers. pp. 196–197. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

External links

- "purgatory". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009.