History of Stamford, Connecticut

The history of Stamford, Connecticut

Early history

Stamford was known as Rippowam by the Siwanoy Native American inhabitants to the region, and the very first European settlers to the area also referred to it that way. The name was later changed to Stamford after a town in Lincolnshire, England. The deed to Stamford was signed on 1 July 1640 between Captain Turner of the New Haven Colony and Chief Ponus. The land that now forms the city of Stamford was bought for 12 coats, 12 hoes, 12 ratchets, 12 glasses, 12 knives, four kettles, and four fathoms of white wampum. The deed was renegotiated several times until 1700 when the territory was given up by the Native American inhabitants for a more substantial sum of money.

In 1641, Rippowam was settled by 29 Puritan families who had chosen to leave Wethersfield.[1] The group had formed "The Rippowam Company" and contracted with the New Haven Colony to settle the Rippowam area.[2] Hence initially the settlement was a part of the New Haven Colony, as was Greenwich to the west.[2] The name of the settlement was changed to Stamford on April 6, 1642.[2] In 1642, Captain John Underhill settled in Stamford and the following year represented the town in the New Haven Colony General Court. Stamford was included in the creation of a New Haven confederation called the United Colonies of New England. Other towns or plantations in the United Colonies of New England included Milford and Guilford in Connecticut as well as Southold on Long Island.[3] Shortly after the restoration of Charles II of England, in a session of the Connecticut General Court held on October 9, 1662 the former New Haven "plantations" of Stanford (sic), Greenwich, Guilford, and even Southold were to be recognized as Connecticut Colony towns with constables sworn in.[4]

The first public schoolhouse in Stamford was a "crude, unheated wooden structure only ten or twelve feet square". It was built in 1671 when settlers tore down their original meeting house, which they had outgrown after three decades, and used some of the timbers to put up a school near the Old Town Hall on Atlantic Square. On the nearby common they built a new 38-foot-square (12 m) meeting house, which also served as the Congregational church.[5] In 1838 William Betts founded Betts Academy in Stamford which operated until it burned in 1908.[6]

On 22 July 1781, during the American Revolutionary War, Stamford was raided by the British. Fort Stamford was built as a result.[7]

One of the primary industries of the small colony was merchandising by water, which was possible due to Stamford's proximity to New York.

Starting in the late 19th century, New York residents built summer homes on the shoreline, and even back then there were some who moved to Stamford permanently and started commuting to Manhattan by train, although the practice became more popular later.

The densely settled portion of Stamford incorporated as a borough in 1830, and later as a city in 1893. The city consolidated with the rest of the non-city portions of the town of Stamford in 1949 to become the present city of Stamford.

Twentieth century

On Memorial Day, 1901, a cannon from the USS Kearsarge was placed in West Park (now Columbus Park) as a memorial to Civil War veterans. Cast at West Point in 1827, the cannon had also been used on the USS Lancaster. The artillery piece sat in the park until 1942 when it was hauled away for scrap.[8]

In 1904, the Town Hall burnt down. A new building in the Beaux Arts style was constructed from 1905 (when the cornerstone was laid) to 1907 in the triangular block formed by Main, Bank and Atlantic streets. The building was eventually named Old Town Hall and held the mayor's office until about 1961, when Mayor William Kennedy moved to the Municipal Office Building which formerly stood further south on Atlantic Avenue. Nearly all municipal offices were moved to 888 Washington Blvd. in 1988.[9]

On February 19, 1919, at the site of the present Cove Island Park, in the Cove section of Stamford, the Cove Mill factory of the Stamford Manufacturing Company burned to the ground in a spectacular conflagration.

Stamford is the birthplace of the electric dry shaver industry. By 1940 Colonel Jacob Schick employed almost 1,000 workers at the Schick Dry Shaver Company on Atlantic Street.[10]

Downtown development

By the mid-1950s downtown Stamford had fallen prey to severe urban blight. A once vibrant downtown became littered with vacant storefronts, empty lots, weak economy, unsafe and unsanitary housing. The town leaders at the time sought federal and state funding to launch a revitalization effort that would restore the core of the city to a vital urban center. On January 27, 1960 the City of Stamford and its redevelopment arm, the Urban Redevelopment Commission, entered into a contract with the Stamford New Urban Corporation, a subsidiary of the locally based and nationally active construction contractor the F. D. Rich Company that would lead to a dramatic altering of the face of downtown Stamford. The Rich Company, led by Frank D. Rich Jr., Robert N. Rich and Chief Legal Counsel Lawrence Gochberg, actively building in 25 of the 50 United States at the time, was selected out of a field of 10 developers vying for the opportunity to become the city's sole redeveloper of the 130-acre (0.53 km2) section of the central downtown area known as the Southeast Quadrant. More than $100 million in Federal, State and city funds were invested in a massive property acquisition, relocation, demolition and infrastructure creation program that paved the way for one of the most sweeping urban renewal efforts ever successfully carried out in the United States. The plan, which involved eminent domain takings, the relocation of 1,100 families and 400 businesses, was implemented amidst much controversy and several lawsuits that delayed the start of the project until 1968 when construction commenced on the three round apartment towers, St. John's Towers. These buildings still contain 360 apartments and originally served as relocation housing for some of the displaced residents. Most of the deteriorated buildings were razed to make way for the new downtown, resulting in a lack of historic buildings and a downtown that looks more contemporary and modern as compared to some its New England counterparts. The redevelopment was contentious, with groups of residents suing to prevent the demolition of nine city blocks and the displacement of businesses and families.[11]

Although the original plan was more modest in scope, involving light industrial buildings with a motor hotel along Tresser Blvd. and an open-air shopping promenade planned for East Main Street, the city and the redeveloper took advantage of an opportunity to capitalize on corporate moves out of NYC. Although One Landmark Square was completed in 1972, a 300,00 SF office building which for 37 years was the city's tallest, it was the completion of the GTE World Headquarters in 1973 that became the catalyst for downtown office development, setting an example for other corporations seeking a less expensive labor pool, a more favorable income tax structure and lower operating costs. Since then, the downtown renewal area has seen the construction of more than 8 million SF of office space, 1.5 million SF of retail space including the Stamford Town Center Mall, 2,500 units of housing, near 80 restaurants have been added, three movie theaters, a branch of the University of Connecticut and two performing arts venues, the Rich Forum and the Palace Theater. Since the redevelopment, the city has had five department stores, with Macy's, Lord & Taylor, and Saks still present. The site of Bloomingdale's is now part of UCONN's campus and Filene's is now Barnes & Noble. In all, the city contains almost 17 million SF of office space. The intensely developed central business district is just 3 percent of the city's 39 square miles (101 km2); the rest is heavily residential. Much of the city, especially in North Stamford, remained woodsy.

The few historic buildings include the Old Town Hall (1905, currently unoccupied), the Hoyt Barnum House (1699), and the old Yale and Towne building (1869, part of the Yale and Towne complex was destroyed in a fire on April 3, 2006), which was once a lock company (the city seal has the two keys from it). The Yale and Towne property, owned for many years by Samuel Heyman, was sold in 2006 to a syndicate of investors and developers who are in the midst of redeveloping it into a complex of residential and retail buildings. Stretches of Atlantic and Bedford Streets remain essentially as they were originally constructed.

After building High Ridge Park, a suburban corporate campus, in the 1960s, the F. D. Rich Company put up the city's tallest structure, Landmark Building, and the GTE building (now One Stamford Forum), both designed by Victor Bisharat. The Stamford Marriott (also Bisharat), with a revolving restaurant at the top, overlooking Long Island Sound, is another F. D. Rich landmark that changed the look of Downtown.[11]

In the 1980s Frank D. Rich III, Susan M. Rich and Thomas L. Rich joined the company playing major roles in the redevelopment of the city. In 1980 F.D. Rich Co. completed 10 Stamford Forum, a 250,000 SF office building (designed by Steven M. Goldberg of the New York office of Mitchell/Giurgola),[12] and throughout the 1980s it built the 1,000,000-square-foot (93,000 m2) Stamford Town Center mall, 4 Stamford Forum (designed by Cesar Pelli), 6 Stamford Forum (Arthur Erickson) and 8 Stamford Forum (Hugh Stubbins), 300 Atlantic Street (Aldo Giurgola) and 177 Broad Street. When his estate prices collapsed in the late 1980s, the company had to sell some of its homes but continued to own the Stamford Town Center Mall, High Ridge Park and key downtown parcels.

Many of the buildings along Tresser Boulevard, parallel to Interstate 95, had little but street-level lobby spaces, garage entrances and exits accessing the street, although they presented a modern, glittering glass facade to travelers along the highway. The Rich family (which still owns F. D. Rich Co. led by President and CEO, Thomas L. Rich) was criticized for creating pedestrian-unfriendly streets, and Tresser Boulevard became notorious among many architecture and urban design critics. Facts that shaped the pedestal design of the office buildings south of Tresser that are little known are as follows. The high water table in that area prohibited the development of multiple levels of underground parking. Therefore, parking needed to be supplied in above-ground structures which served as podiums for the office buildings providing the opportunity for a view over the adjacent highway embankment to the south. The lack of retail along the Tresser Blvd. frontage is attributable to a prohibition on retail being developed in this area by the Planning Board of the City who did not want to dilute the retail existing and planned elsewhere in the renewal area.

"The streets were never meant to be for pedestrians," Robert N. Rich, then head of the company, told a reporter for the New York Times in 1999, apparently referring to Tresser Boulevard and the immediate area around it. "GTE came here because they were bombed in New York. Crime was a problem in the city. That's why the buildings were designed to be impenetrable."[11]

Over the years, other developers have joined F. D. Rich Co. in building up the downtown, including Avalon, Archstone-Smith, Seth Weinstein and Paxton Kinol who have developed many four-story rental apartment buildings. Corcoran-Jenninsen constructed Park Square West apartments on lower Summer Street. The Michigan-based Taubman Company partnered with F. D. Rich Co. in developing the Stamford Town Center Mall. UBS and RBS, taking advantage of state and local tax incentive programs, built their headquarters in downtown Stamford. W&M Properties built and owns Metro Center, a prominent building just south of the Stamford train station where Thomson Corporation, officially a Canadian company, has its operational headquarters. Today most of the downtown office buildings are owned by RFR Realty and S. L. Green.

F. D. Rich Co., still located in downtown Stamford, sold or gave up nearly all of its Stamford buildings (including the Landmark) in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The company developed and owns the Bow Tie Majestic Cinema building, much of the retail and office space on lower Summer Street. Along with the Kahn Family, they brought Target to their Broad Street location on land they jointly owned. Rich and Kahn own the ground floor retail space under Target facing Broad Street. In 2005, the company opened its 115-room Courtyard by Marriott Hotel at the corner of Summer and Broad Streets, which houses the restaurant Napa & Company. F. D. Rich Co., with partners Donald Trump and Louis R. Cappelli, built the Trump Parc Stamford, a 170-unit, 34-story condominium tower which was the tallest building in the city at the time of its opening in 2009, eclipsing One Landmark Square by more than 80 feet (24 m) in height. F. D. Rich Co. and Cappelli Enterprises own a site at the corner of Atlantic Street and Tresser Blvd. which has been approved for his twin 400-foot-tall (120 m) towers slated to contain a 198-room Ritz Carlton Hotel, 600,000 SF of condominiums and 70,000 SF of retail space including the restoration of the Atlantic Street Station post office. The Rich Forum, a downtown performing arts center and the Rich Concourse, the main public space at the downtown branch of UConn are both named after the Rich family. Lowe Enterprises controls a site on Tresser and Washington Blvd that has been approved for three 350-foot-tall (110 m) residential towers slated to contain 835 units of for sale and rental housing along with 135,000 SF of retail space fronting Tresser Blvd.

Twenty-first century

On September 11, 2001, nine city residents lost their lives in the 9/11 attacks, all at the World Trade Center: Alexander Braginsky, 38; Stephen Patrick Cherry, 41; Geoffrey W. Cloud, 36; John Fiorito, 40; Bennett Lawson Fisher, 58; Paul R. Hughes, 38; Sean Rooney, 50; Randolph Scott, 48; and Thomas F. Theurkauf Jr., 44. A total of 65 Connecticut residents lost their lives on that day.[13]

One of the biggest fires in Stamford's history occurred April 3, 2006 in the South End. The fire started in a piano store in a building that was part of the former Yale & Towne lock factory complex. It spread to a neighboring building housing antiques dealers. Eight businesses were destroyed and others were damaged. City fire marshals never determined the cause, but said an unfixed sprinkler system helped the fire spread. Firefighters used 1 million gallons (3,800,000 l) of water in three hours and then had to pump water from Long Island Sound when the water mains ran out. Dark mushroom clouds formed over the scene, visible for miles along Interstate 95. About 200 residents from homes on Pacific and Henry streets were evacuated. In July 2006, more than 100 antiques dealers filed a class-action lawsuit against the owner, Antares Real Estate Services of Greenwich.[14]

In recent years, Stamford has appeared as a setting in some television shows: In the NBC television series The Office, the character Jim Halpert transferred to a Dunder Mifflin branch in Stamford. The sitcom My Wife and Kids is set in Stamford. An episode of The Cosby Show mentioned a neighborhood supermarket chain as being based in Stamford.

In the early afternoon of August 3, 2006, one of the hottest days of the year when air conditioning raised electricity consumption, downtown Stamford experienced a blackout after underground electricity cables on Summer Street overheated and caught fire. Many offices were forced to close down. A concert (part of the Alive@Five series) with Hootie & the Blowfish continued at Columbus Park early that evening, but many restaurants had to throw out their food beforehand.

Stamford was (fictionally) devastated in a 2006 Marvel Comics miniseries called Civil War. The story depicted a group of superheroes being filmed for a reality television show as they raided a suburban home being used as the safehouse for a group of supervillains, one of whom, Nitro, used his power to explode to destroy the neighborhood. Although no specific Stamford buildings seem to be depicted, a store sign from A Timeless Journey" a local comic book shop, is featured in Issue The Amazing Spider-Man #532. Marvel writer Jeph Loeb, who grew up near Riverbank Road and attended the former Riverbank Elementary School, came up with the decision to use Stamford, according to an article in The Advocate of Stamford. The use of the comic-book store sign came because the store owner, Paul Salerno, was quoted in an April Advocate story saying he'd love to have his store depicted, even if it were devastated in the series. The day after the article came out, the store owner got a call from Marvel.[15][16] Stamford had previously appeared in Marvel Comics as the location of the suburban home of Mr. Fantastic and the Invisible Woman of the Fantastic Four, at a time when the married couple were semi-retired as superheroes and attempting to establish a "normal" home life for their son Franklin.

On October 11, 2007, a freak storm dumped 5 inches (130 mm) of rain in about four hours in Stamford and nearby communities of New Canaan, Darien and Norwalk. The storm flooded streets and basements and caused the loss of electricity to 700 homes, with about 20 people needing to be evacuated from their cars and 40 others removed from their homes to an emergency shelter. The Federal Emergency Management Agency later said 41 homes in Stamford (and 11 in Darien and New Canaan) had about $167,000 in damage. City sewers and drains were clogged. The city was sued in 2009 by homeowners who asserted that a city employee failed to start a pumping station on Dyke Street soon enough, but a city lawyer called the event a "100-year storm" that simply overwhelmed municipal resources.[17]

Since 2008, an 80-acre mixed-use redevelopment project for the Stamford's Harbor Point neighborhood has added additional growth south of the city's Downtown area. Once complete, the redevelopment will include 6,000,000 square feet (560,000 m2) of new residential, retail, office and hotel space, and a marina. As of July 2012, roughly 900 of the projected 4,000 Harbor Point residential units had been constructed.[18]

Controversies

Ku Klux Klan in Stamford

The Ku Klux Klan, which preached a doctrine of Protestant control of America and suppression of blacks, Jews and Catholics, had a following in Stamford in the 1920s. Across the state, the Klan's popularity peaked in 1925 when it had a statewide membership of 15,000. Stamford was one of the communities where the group was most active in the state, although New Haven and New Britain were also centers of support.[19]

During the 1924 election, one of the largest Klan meetings in the state took place in Stamford. Grand Dragon Harry Lutterman of Darien organized the meeting, attended by thousands of Klansmen.[19]

The Stamford Republican Party used its Lincoln Republican Club as a front for all Klan activities in the area. The Stamford Advocate (as The Advocate of Stamford was then known) published an advertisement signed by local Democrats (who relied on the Catholic vote) protesting the meeting. The Klan published an advertisement in response, noting the "un-American" names of some of those who signed the Democrats' statement.[19]

By 1926, the Klan leadership in the state was divided, and it lost strength, although it continued to maintain small, local branches for years afterward in Stamford, as well as in Bridgeport, Darien, Greenwich and Norwalk.[20]

Pictures

Massee School for Boys, about 1921

Massee School for Boys, about 1921 Rippowam River, about 1905

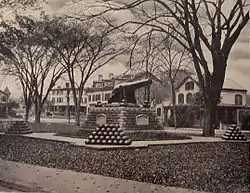

Rippowam River, about 1905 Atlantic Square, ca. 1908

Atlantic Square, ca. 1908

On the National Register

- Agudath Shalom Synagogue—29 Grove St. (added June 11, 1995)

- Benjamin Hait House—92 Hoyclo Road (added December 30, 1978)

- C. J. Starr Barn and Carriage House—200 Strawberry Hill Ave. (added October 14, 1979)

- Church of the Holy Name—305 Washington Blvd. (added 1987)

- Cove Island Houses—Cove Road and Weed Avenue (added June 22, 1979)

- Deacon John Davenport House—129 Davenport Ridge Road (added May 29, 1982)

- Downtown Stamford Historic District—Atlantic, Main, Bank, and Bedford Sts. (added November 6, 1983)

- Downtown Stamford Historic District (Boundary Increase 2)—Roughly, Bedford Street between Broad and Forest Streets (added February, 2003)

- Fort Stamford Site (added October 10, 1975)

- Gustavus and Sarah T. Pike House—164 Fairfield Ave. (added June 24, 1990)

- Hoyt-Barnum House—713 Bedford St. Moved 2016 new location 1508 High Ridge Road (added July 11, 1969)

- John Knap House—984 Stillwater Road (added April 5, 1979)

- Linden Apartments—10-12 Linden Place (added September 11, 1983)

- Long Ridge Village Historic District—Old Long Ridge Road bounded by the New York State Line, Rock Rimmon Road, and Long Ridge Road (state Route 104) (added July 2, 1987)

- Main Street Bridge—Carries Main Street over the Rippowam River (added June 21, 1987)

- Marion Castle, Terre Bonne—1 Rogers Road (added August 1, 1982)

- Nathaniel Curtis House—600 Housatonic Ave. (added May 15, 1982)

- Octagon House—120 Strawberry Hill Ave. (added September 17, 1979)

- Old Town Hall—between Atlantic, Bank, and Main Streets (added July 2, 1972)

- Revonah Manor Historic District—Roughly bounded by Urban Street, East Avenue, Fifth, and Bedford Streets (added August 31, 1986)

- Rockrimmon Rockshelter (added September 5, 1994)

- South End Historic District—Roughly bounded by Metro-North railroad tracks, Stamford Canal, Woodland Cemetery, and Washington Boulevard (added April 19, 1986)

- St. Andrew's Protestant Episcopal Church—1231 Washington Blvd. (added 1983)

- St. Benedict's Church—1A St. Benedict's Circle (added 1987)

- St. John's Protestant Episcopal Church—628 Main St. (added 1987)

- St. Luke's Chapel—714 Pacific St. (added 1987)

- St. Mary's Church—540 Elm St. (added 1987)

- Stamford Harbor Lighthouse—South of breakwater, Stamford Harbor (added May 3, 1991)

- Suburban Club—6 Suburban Ave./580 Main St. (added September 10, 1989)

- Turn-of-River Bridge—Old North Stamford Road at Rippowam River (added August 31, 1987)

- US Post Office-Stamford Main—421 Atlantic St. (added 1985)

- Unitarian Universalist Society in Stamford—20 Forest St. (added 1987)

- Zion Lutheran Church—132 Glenbrook Road (added 1987)

Footnotes

- Charles, Eleanor, "If You're Thinking of Living in: Stamford", an article in The New York Times, August 20, 1989, accessed April 29, 2007

- "Stamford Historical Society, Davenport Exhibit - Stamford's Colonial Period 1641-1783". Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- Atwater, Edward E. (1881). "Chapter IX". History of New Haven Colony. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- "Connecticut Colonial Records (volume 01, page 408/page 388)". Archived from the original on 2002-06-03. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- Updegraff, Mary, "Education Spelled Freedom" article at the Stamford Historical Society Web site, accessed April 13, 2007

- Spelled Freedom" From:Stamford Past & Present, 1641 – 1976 The Commemorative Publication of the Stamford Bicentennial Committee (Stamford Historical Society http://www.stamfordhistory.org/pp_ed.htm)

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

- Bull, Bonnie K., Stamford "Images of America" series of books, Arcadia Publishing: 2004. ISBN 0-7385-3457-9 Retrieved from Google Books on March 8, 2008

- Dalena, Doug, "100 years ago, Old town hall had something new to offer", article in The Advocate of Stamford, page 1, Stamford and Norwalk editions

- "About the Avon" web page at web site for the Avon Theatre, accessed 28 June 2006

- New York Times article, "Commercial Property/Stamford, Conn.: A Pioneer Business Park That Confounded Critics," by Eleanor Charles, Sept. 26, 1999 Page accessed on 23 June 2006

- Horsley, Carter B., "About Real Estate: Offices Designed to Serve as an Entry to Stamford," New York Times, August 26, 1981, accessed August 9, 2006

- Associated Press listing as it appeared in The Advocate of Stamford, September 12, 2006, page A4

- Lee, Natasha, "South End blaze costs millions: Antiques dealers still displaced after fire", article in The Advocate of Stamford, December 31, 2006

- Lockhart, Brian, "An explosion of INK: Stamford comic shop destroyed in pages of 'The Amazing Spider-Man'," article in The Advocate of Stamford, June 3, 2006, pages 1, A4

- Tabu, Hannibal; "WWLA: Cup o' Jeph"; comicbookresources.com; March 14, 2008.

- Potts, Monica, "Lawsuit alleges negligence before '07 storm", The Advocate of Stamford, Connecticut, p 1, October 13, 2009

- Connecticut Post article, "Trending: Why One City is Booming", by Maggie Gordon, May 23, 2013 Page accessed on May 26, 2013

- DiGiovanni, the Rev. (now Monsignor) Stephen M., The Catholic Church in Fairfield County: 1666-1961, 1987, William Mulvey Inc., New Canaan, Chapter II: The New Catholic Immigrants, 1880-1930; subchapter: "The True American: White, Protestant, Non-Alcoholic," pp. 81-82; DiGiovanni, in turn, cites (Footnote 209, page 258) Jackson, Kenneth T., The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930 (New York, 1981), p. 239

- DiGiovanni, the Rev. (now Monsignor) Stephen M., The Catholic Church in Fairfield County: 1666-1961, 1987, William Mulvey Inc., New Canaan, Chapter II: The New Catholic Immigrants, 1880-1930; subchapter: "The True American: White, Protestant, Non-Alcoholic," p. 82; DiGiovanni, in turn, cites (Footnote 210, page 258) Chalmers, David A., Hooded Americanism, The History of the Ku Klux Klan (New York, 1981), p. 268

External links

Stamford Historical Society links

- Stamford Historical Society Web site

- "Stamford Connecticut, 1641 - 1893: the first two-and-a-half centuries" by Dr. Estelle F. Feinstein

Stamford Historical Society "Condensed History of Stamford" online articles: