History of Naples

The history of Naples is long and varied, dating to Greek settlements established in the Naples area in the 2nd millennium BC.[1] During the end of the Greek Dark Ages a larger mainland colony – initially known as Parthenope – developed around the 9-8th century BC,[2] and was refounded as Neapolis in the 6th century BC:[3] it held an important role in Magna Graecia. The Greek culture of Naples was important to later Roman society. When the city became part of the Roman Republic in the central province of the Empire, it was a major cultural center.[4] Virgil is an example of the political and cultural freedom of Naples.

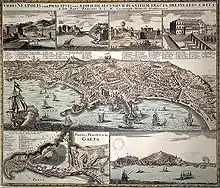

For centuries, Naples was the capital of the kingdom of Naples. The city has seen the rise and fall of several civilizations and cultures, each of which has left traces in its art and architecture, and during the Renaissance[5] and the Enlightenment was a major center of culture.[6] During the Neapolitan War, the city rebelled against the Bourbon monarchs, spurring the early push towards Italian unification.

Today, Naples is part of the Italian Republic, the third largest municipality (central area) by population after Rome and Milano, and has the second or third largest metropolitan area of Italy.

Greek birth, Roman acquisition

The Naples area has been inhabited since the Stone Age.

Settlers from two cities in Euboea, Greece, jointly colonised the nearby Cumae, the earliest Greek city on mainland Italy. The earliest founding of Naples itself is claimed in legend to be the Greek colony Phaleron (Latin: Phalerum), after the hero Phaleros, one of the Argonauts.[7][8]

However, the first Greek settlements had been established on the site during the 2nd millennium BC. At the end of the Greek Dark Ages a larger mainland colony – initially known as Parthenope – developed around the 9-8th century BC. Parthenope was the name of the siren in Greek mythology, said to have washed ashore at Megaride, having thrown herself into the sea after she failed to bewitch Ulysses with her song. Around this time Greeks became locked in a power struggle with the Etruscans, who sought to dominate the area. Etruscans attacked Cumae (524 BC) and, although the attack failed, it signaled a growing Etruscan determination to dominate the area, the pressure of which pushed Parthenope to the commercial margins. There is evidence that the city had slid into decadence and, some argue, had virtually ceased to exist. However, literary evidence shows that the city was destroyed because the hegemony of Cumae was threatened.

Recent archaeological discoveries show that, in the 6th century (not in the 470 BC, after the battle of Cumae), the city was refounded and the new urban zone of Neapolis (Νεάπολις) was founded inland, eventually becoming one of the foremost cities of Magna Graecia. The primitive center of Parthenope on the hill of Pizzofalcone came to be called simply Palaipolis (Latin: Palaepolis), the "old city". Neapolis had a powerful line of walls, in front of which the Carthaginian invader Hannibal had to retreat when the city was allied with the Romans. Other features were an odeon and a theatre, and the temple of the city's patron gods, the Dioscuri. Although conquered by the Samnites during the fifth century BC,[9] and then the Romans,[10] Naples long retained its Greek culture; it is significant that modern Neapolitans still refer to themselves often as Partenopei, lit. 'Parthenopeans'.

In the Roman era the city was a flourishing centre of Hellenistic culture that attracted Romans who wished to perfect their knowledge of Greek culture. The pleasant climate made it a renowned resort, as recounted by Virgil and manifested in the numerous luxurious villas that dotted the coast from the Gulf of Pozzuoli to the Sorrentine peninsula. The famous district of Posillipo takes its name from the ruins of Villa Pausílypon, meaning, in Greek, "a pause, or respite, from worry". Romans connected the city to the rest of Italy with their famous roads, excavated galleries to link Naples to Pozzuoli, enlarged the port, and added public baths and aqueducts to improve the quality of life in Naples. The city was also celebrated for its many feasts and spectacles.

According to legend, the saints Peter and Paul came to the city to preach. Christians had a prominent role in the late years of the Roman Empire, and there are several notable catacombs, especially in the northern part of the city. The first palæo-Christian basilicas were built next to the entrances to the catacombs. The greatly popular patron of the city, San Gennaro (St. Januarius), was decapitated in nearby Pozzuoli in AD 305, and, since the 5th century, he has been commemorated by the basilica of San Gennaro extra Moenia. The Cathedral of Naples is also dedicated to St. Gennaro.

It was in Naples, in Lucullus' Villa in what is now the Castel dell'Ovo, that Romulus Augustulus, the last nominal western emperor was imprisoned after being deposed in 476. Naples suffered much during the Gothic Wars between the Ostrogoths and the Byzantines during the 6th century. In 536, it decided to resist Belisarius's invasion. However, his troops captured the city by entering through its aqueduct. With the changing tide of the war in the 540s, it was starved into surrender by Totila, who treated it leniently. During Narses's expedition during the 550s, it was captured by the Empire once again. When the Lombards invaded and conquered much of Italy in the following years, Naples remained loyal to the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Duchy of Naples

At the time of the Lombard invasion, Naples had a population of about 30,000-35,000. In 615, under Giovanni Consino, Naples rebelled for the first time against the Exarch of Ravenna, the emperor's plenipotentiary in Italy. In reply, the first form of duchy was created in 638 by the Exarch Isaac or Eleutherius (exarchic chronology is uncertain), but this official came from abroad and had to answer to the strategos of Sicily. At that time the Duchy of Naples controlled an area corresponding roughly to the present day Province of Naples, encompassing the area of Vesuvius, the Campi Flegrei, the Sorrentine peninsula, Giugliano, Aversa, Afragola, Nola and the islands of Ischia and Procida. Capri was later part of the duchy of Amalfi

In 661 Naples, with the permission of the emperor Constans II, was ruled by a local duke, Basilius, whose allegiance to the emperor soon became merely nominal. In 763 the duke Stephen II switched his allegiance from Constantinople to the Pope. In 840 Duke Sergius I made the succession to the duchy hereditary, and thenceforth Naples was de facto totally independent. At this time the city was mainly a military centre, ruled by an aristocracy of warriors and landowners, even though it had been forced to surrender to the neighbouring Lombards much of its inland territory. Naples was not a merchant city as were other Campanian sea cities such as Amalfi and Gaeta, but had a respectable fleet that took part in the Battle of Ostia against the Saracens in 849. In any event, Naples did not hesitate to ally itself with infidels if it proved advantageous to do so: in 836, for example, Naples asked for support from the Saracens in order to repel the siege of Lombard troops coming from the neighbouring Duchy of Benevento. Later, Muhammad I Abu 'l-Abbas led its Muslim conquest of Naples and managed to sack it and take huge amount of its wealth.[11][12] After Neapolitan dukes rose to prominence under the Duke-Bishop Athanasius and his successors (among these, Gregory IV and John II participated at the Battle of the Garigliano in 915), Naples declined in importance in the 10th century until it was captured by its traditional rival, Pandulf IV of Capua.

In 1027, duke Sergius IV donated the county of Aversa to a band of Norman mercenaries led by Rainulf Drengot, whose support he had needed in the war with the principality of Capua. In that period he could not imagine the consequences, but this settlement began a process which eventually led to the end of the independence of Naples.

Last of the rulers of such independent southern Italian states, Sergius VII was forced to surrender to Roger II of Sicily in 1137; Roger had had himself proclaimed king of Sicily seven years earlier. Under the new rulers, the city was administrated by a compalazzo (palatine count), with little independence left to the Neapolitan patriciate. In this period Naples had a population of 30,000 and was sustained by its holdings in the interior; commerce was mainly delegated to foreigners, mainly from Pisa and Genoa.

Apart from the church of San Giovanni a Mare, Norman buildings in Naples were mainly lay ones, notably castles (Castel Capuano and Castel dell'Ovo), walls and fortified gates.

_(front_view)._Naples%252C_Campania%252C_Italy%252C_South_Europe.jpg.webp)

Normans, Hohenstaufen, and Anjou

After a period of Norman rule, in 1189 the Kingdom of Sicily was in a succession dispute between Tancred, King of Sicily of an illegitimate birth and the Hohenstaufens, a German royal house,[13] as its Prince Henry had married Princess Constance the last legitimate heir to the Sicilian throne. In 1191 Henry invaded Sicily after being crowned as Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor and many cities surrendered, but Naples resisted him from May to August under the leadership of Richard, Count of Acerra, Nicholas of Ajello, Aligerno Cottone and Margaritus of Brindisi before the Germans suffered from disease and were forced to retreat. Conrad II, Duke of Bohemia and Philip I, Archbishop of Cologne died of disease during the siege. In light of this Tancred achieved another unexpected achievement that his contender Constance, now empress, was captured at Salerno while those cities surrendered to Germans resubmitted to Tancred. Tancred had the empress imprisoned at Castel dell'Ovo at Naples before her release in May 1192. In 1194 Henry started his second campaign upon the death of Tancred, but this time Aligerno surrendered without resistance, and finally Henry conquered Sicily, putting it under the rule of Hohenstaufens.

Frederick II Hohenstaufen founded the university in 1224, considering Naples as his intellectual capital while Palermo retained its political role. The university remained unique in southern Italy for seven centuries. After the defeat of Frederick's son, Manfred, in 1266 Naples and the kingdom of Sicily were assigned by Pope Clement IV to Charles of Anjou, who moved the capital from Palermo to Naples. He settled in his new residence in the Castel Nuovo, around which a new district grew up, marked by palaces and residences of the nobility. During Charles' reign new Gothic churches were also built, including Santa Chiara, San Lorenzo Maggiore and the Cathedral of Naples.

After the Sicilian Vespers (1284), the kingdom was split in two parts, with an Aragonese king ruling the island of Sicily and the Angevin king ruling the mainland portion; while both kingdoms officially called themselves the Kingdom of Sicily, the mainland portion was commonly referred to as the Kingdom of Naples. The Hungarian Angevin king Louis the Great captured the city several times. The kingdom had been divided in two, but Naples grew in importance: Pisan and Genoese merchants were joined by Tuscan bankers, and with them came outstanding artists such as Boccaccio, Petrarca, and Giotto.

See also Kingdom of Naples

The Aragonese period

In 1442 Alfonso I conquered Naples after his victory against the last Angevin king, Rene, and made his triumphal entry into the city in February 1443. The new dynasty enhanced commerce by connecting Naples to the Iberian peninsula and made Naples a centre of the Italian Renaissance: artists who worked in Naples in this period include Francesco Laurana, Antonello da Messina, Jacopo Sannazzaro and Angelo Poliziano. The court also granted land holdings in the provinces to the nobility; this, however, had the effect of fragmenting the kingdom.

After the brief conquest by Charles VIII of France in 1495, the two kingdoms were united under Aragonese rule in 1501. In 1502 Castilian general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba entered in the city. Although Fernández de Córdoba was Castilian, he conquered under the command of Ferdinand II of Aragon. Ferdinand and his wife Isabella I of Castile ruled their kingdoms jointly in personal union during their marriage. But the partnership of the Catholic Monarchs ceased with Isabella's death in 1504, and Ferdinand expelled the Castilians from leadership in Aragonese possessions in Italy, including Naples.[14] The conquest began nearly two centuries of rule of the almost omnipotent viceré ("viceroys") in Naples.

Under the viceroys Naples grew from 100,000 to 300,000 inhabitants, second only to Istanbul in Europe. The most important of them was don Pedro Álvarez de Toledo: he introduced heavy taxation and favoured the Inquisition, but at the same time improved the conditions of Naples. He opened the main street, which still today bears his name; he paved other roads, strengthened and expanded the walls, restored old buildings, and erected new buildings and fortresses, essentially turning the city of Naples by 1560 into the largest and best fortified city in the Spanish empire. In the 16th and 17th century Naples was home to great artists such as Caravaggio, Salvator Rosa and Bernini, philosophers such as Bernardino Telesio, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella and Giambattista Vico, and writers such as Gian Battista Marino, thus confirming itself among the most important capitals of Europe. All these cultural figures contributed to the aesthetic and intellectual transformations leading to a new era, commonly defined as Baroque.[15] Patrons and salon-holders such as Aurora Sanseverino, Isabella Pignone del Carretto and Ippolita Cantelmo Stuart had a significant role in the artistic and cultural life in Naples.[16]

All the strains of an increasingly over-populated city exploded in July 1647, when the legendary Masaniello led the populace in violent rebellion against the foreign, oppressive rule of the Spanish. Neapolitans declared a Republic and asked France for support, but the Spaniards suppressed the insurrection in April of the following year and defeated two attempts by the French fleet to land troops. In 1656 the plague killed almost half of the inhabitants of the city; this led to the beginning of a period of decline.

1714 to 1799

The Spanish Habsburgs were replaced in 1714 by Austrian ones, until in 1734 the two kingdoms were united under a single independent crown (Utriusque Siciliarum), that of Charles of Bourbon. Charles renovated the city with the Villa di Capodimonte and the Teatro di San Carlo, and welcomed the philosophers Giovan Battista Vico and Antonio Genovesi, the jurists Pietro Giannone and Gaetano Filangieri, and the composers Alessandro and Domenico Scarlatti. This first king of the House of Bourbon tried to introduce legislative and administrative reforms, but they were stopped as the first news of the French Revolution reached the city. By that time, Charles' son, Ferdinand IV was king, and he entered an anti-French Coalition with Great Britain, Russia, Austria, Prussia, Spain, and Portugal.

The population of Naples at the beginning of the 19th century was mostly made up of a mass of people, who were called the lazzarone and lived in extremely poor conditions. As well, there was a strong royal bureaucracy and an élite of landowners. When in January 1799 French revolutionary troops entered the city they were hailed by a pro-revolutionary minor part of the middle class, but had to face strong resistance by the royalist lazzari, who were fervidly religious and did not support the new ideas. The short-lived Neapolitan Republic tried to gain popular support by abolishing feudal privileges, but the mass of the people rebelled and in June 1799 the republicans surrendered. Upon the order of the restored monarchy, Admiral Horatio Nelson arrested the leaders of the revolution and handed them over for execution Francesco Caracciolo, Mario Pagano, Ettore Carafa, and Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel.[18] Nelson was rewarded by being made Duke of Bronte by the king.[18]

1799-1861

The Parthenopaean Republic in Naples was suppressed by the British and Russians in 1799, and was following in 1805 by a full invasion. In early 1806 Napoleon conquered the Kingdom of Naples. The Emperor Napoleon first named his brother Joseph Bonaparte to be King and then his brother-in-law and Marshal Joachim Murat in 1808, when Joseph was given the Spanish crown. The latter created a communal administration led by a mayor, which was left almost intact by Ferdinand in 1815 as he regained his kingdom after the 1815 Neapolitan War in which the Austrians defeated Murat. In 1839 Naples was the first city in Italy to have a railway, with the Napoli-Portici line.

In spite of a little cultural revival and the proclamation of a Constitution on June 25, 1860, in the last years of the kingdom the gap between the court and the intellectual class continued to grow.

On September 6, 1861, the kingdom was conquered by the Garibaldines and was handed over to the King of Sardinia: Garibaldi entered the city by train, descending in the square that today still bears his name. In October 1860 a plebiscite sanctioned the end of the Kingdom of Sicily and the birth of new Italian state, the United Kingdom of Italy.

Contemporary age

The opening of the funicular railway to Mount Vesuvius was occasion for the writing of the famous song "Funiculì, Funiculà", one more song in the centuries long tradition of Neapolitan song. Many Neapolitan songs are also famous outside of Italy, as for example "O Sole Mio", "Santa Lucia" and "Torna a Surriento". On April 7, 1906 nearby Mount Vesuvius erupted, devastating Boscotrecase and seriously damaging Ottaviano.

During World War II, Naples was the first Italian city to rise up against the Nazi military occupation; between September 28 and October 1, 1943 the people of the city rose up and pushed the Germans out, in what became known as the "four days of Naples". British Armoured patrols of the King's Dragoon Guards were the first allied unit to reach Naples. They were followed by the Royal Scots Greys followed by troops of the US 82nd Airborne Division; they found Naples already free, and continued on instead towards Rome.[19]

In 1944 another devastating eruption from Vesuvius occurred; images from this eruption were used in the film The War of the Worlds.

Napoli has turned into the most important transportation hub of southern Italy. The airport of Capodichino has connections with several airports in Europe. The city also has an important port that connects to many Tyrrhenian Sea destinations, including Cagliari, Genoa and Palermo, often with fast ferries. Naples also has ferry connections to nearby islands and Sorrento, and fast rail connections to Rome and the south. It is famous for the light railway Circumvesuviana.

Organised crime is deeply rooted in Naples. The Camorra, the feuding Neapolitan gangs and families, have a long history. During 2004 over 120 people died in Naples in Camorra killings; many of the deaths were related to the drug trade.

Unemployment remains very high in Naples, with some estimates running above 20% among working-age males. The industrial base is still small and a number of earlier and ambitious enterprises such as automobile manufacturing plants on the outskirts have closed and gone elsewhere. There is a large "submerged economy"—meaning the black market—and it is difficult to have reliable statistics on the amount of wealth generated by such activity. Social services in the city have come under recent strain in attempting to deal with the increase in immigration.

In 1927 Naples absorbed some nearby communities; the 1860 population of 450,000 increased to 1,250,000 in 1971.

Cosmetically, at least, Naples improved in the two decades either side of the turn of the 21st century: Piazza del Plebiscito, for example, has returned to its historic role as the largest open square in the city instead of being the squalid parking lot that it was between the end of WWII and 1990; city landmarks such as the San Carlo theater and the Galleria Umberto have been restored; a major ring road, the tangenziale di Napoli, has alleviated traffic through and around the city; and major construction continues on the new underground railway system, the Naples Metro (metropolitana di Napoli), which, even its current unfinished state now provides easy transportation for the first time in the history of the city from the upper reaches of the Vomero hill section of the city into the downtown area. As a result of at least some of these improved conditions in the city, tourism has increased. As a matter of fact, Naples became the world's 91st richest city by purchasing power in 2005, with a GDP of US$43 billion, surpassing cities such as Budapest and Zurich,[20] and unemployment decreased dramatically between the 1990s and 2010.[21]

See also

References

- David J. Blackman; Maria Costanza Lentini (2010). Ricoveri per navi militari nei porti del Mediterraneo antico e medievale: atti del Workshop, Ravello, 4–5 novembre 2005. Edipuglia srl. p. 99. ISBN 978-88-7228-565-7.

- "Archemail.it". Archived from the original on 2013-03-29. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- Daniela Giampaola, Francesca Longobardo, Naples greek and roman, Electa Naples 2000

- History of Naples Archived 2010-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Treccani.it

- Duo.uio.no p.4

- "Greek Naples". Faculty.ed.umuc.edu. 8 January 2008. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- "Phalerus". MythIndex.com. 8 January 2008.

- "Touring Club of Italy, Naples: The City and Its Famous Bay, Capri, Sorrento, Ischia, and the Amalfi, Milano". Touring Club of Italy. 2003. p. 11. ISBN 88-365-2836-8.

- Touring Club of Italy, Naples: The City and Its Famous Bay, Capri, Sorrento, Ischia, and the Amalfi, Milano, February 2003

- Magnusson & Goring 1990

- Hilmar C. Krueger. "The Italian Cities and the Arabs before 1095" in A History of the Crusades: The First Hundred Years, Vol.I. Kenneth Meyer Setton, Marshall W. Baldwin (eds., 1955). University of Pennsylvania Press. p.48.

- "Swabian Naples". naplesldm.com. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Charles E. Nowell, "Old World Origins of the Spanish-American Viceregal System" in First Images of America. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1976, p. 225.

- Giardino, Alessandro (2017). Corporeality and Performativity in Baroque Naples. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books Press. ISBN 978-1-4985-6398-7.

- Astarita, Tommaso (2013). A Companion to Early Modern Naples. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-23670-7.

- "View of the Bay of Naples with Admiral Byng's Fleet at Anchor, 1 August 1718". National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

- North, Jonathan (2018). Nelson at Naples, Revolution and Retribution in 1799. Stroud: Amberley. p. 304. ISBN 978-1445679372.

- Fifth Army History, Volume 1. Historical Section, Headquarters Fifth Army. 1945. p. 47.

- "City Mayors reviews the richest cities in the world in 2005". Citymayors.com. 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- "Site3-TGM table". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2010-01-25.