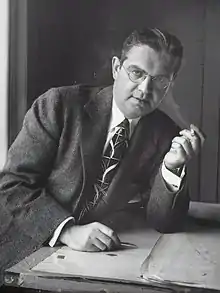

Henry Dreyfuss

Henry Dreyfuss (March 2, 1904 – October 5, 1972) was an industrial design pioneer. Dreyfuss is known for designing some of the most iconic devices found in American homes and offices throughout the twentieth century, including the Western Electric Model 500 telephone, the Westclox Big Ben alarm clock, and the Honeywell round thermostat. Dreyfuss enjoyed long term associations with several name brand companies such as John Deere, Polaroid, and American Airlines.

Henry Dreyfuss | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 2, 1904 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 5, 1972 (aged 68) |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Occupation | Industrial designer |

| Spouse(s) | Doris Marks Dreyfuss |

| Children | 3 |

Career

Dreyfuss, a native of Brooklyn, New York City, is one of the celebrity industrial designers of the 1930s and 1940s who pioneered his field. Dreyfuss dramatically improved the look, feel, and usability of dozens of consumer products. When compared to Raymond Loewy and some other contemporaries, Dreyfuss was much more than a stylist; he applied common sense and a scientific approach to design problems, making products more pleasing to the eye and hand, safer to use, and more efficient to manufacture and repair. His work helped popularize the role of the industrial designer while also contributing significant advances to the fields of ergonomics, anthropometrics and human factors.

Dreyfuss began as a Broadway theatrical designer. Until 1920, he apprenticed under Norman Bel Geddes, who would later become one of his competitors. In 1929 Dreyfuss opened his own office for theatrical and industrial design. His firm quickly met with commercial success, and continued as Henry Dreyfuss Associates for over four decades after his death.

Designs

- Hoover model 150 vacuum cleaner (1936)

- Classic Westclox Big Ben alarm clock (1939–present)[1]

- New York Central Railroad's streamlined Mercury train, both locomotive and passenger cars (1936)[2]

- NYC Hudson locomotive for the Twentieth Century Limited (1938)[2]

- Popular Democracity model city of the future at the 1939 New York World's Fair at the Trylon and Perisphere

280 Park Avenue in Manhattan

280 Park Avenue in Manhattan - Styled John Deere Model A and Model B tractors (1938)

- Wahl-Eversharp Skyline fountain pen (1940)

- Royal Typewriter Company's Quiet DeLuxe (late 1940s)

- Bell System telephones: Western Electric 500-series desk and wall telephones (1949 - 1972), Princess telephone (1959), Model 1500 10 digit touchtone (1963), Model 2500 12-digit touchtone (1968–present), and the Trimline telephone (1965–present)

- Two American steamships, S.S. Independence and S.S. Constitution for American Export Lines (1951–2)

- Honeywell T87 "the Round" circular wall thermostat (1953–present)

- Spherical Hoover model 82 Constellation vacuum cleaner which floated on an air cushion of its own exhaust (1954)

- Hoover model 65 convertible vacuum cleaner (1957)

- John Deere 1010, 2010, 3010, and 4010 tractors (1960)

- Bankers Trust Building at 280 Park Avenue in Manhattan, New York City, with Emery Roth & Sons (1963)[3]

- American Airlines branding (1960s)[4]

- Polaroid SX-70 Land camera (1972)

Later life

In 1955, Dreyfuss wrote Designing for People. A window into Dreyfuss's career as an industrial designer, the book illustrated his ethical and aesthetic principles, included design case studies, many anecdotes, and an explanation of his "Joe" and "Josephine" anthropometric charts. In 1960 he published The Measure of Man, a collection of ergonomic reference charts providing designers precise specifications for product designs. In 1965, Dreyfuss became the first President of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA). In 1969, Dreyfuss retired from the firm he founded,[5] but continued serving many of the companies he worked with as board member and consultant. In 1972 Dreyfuss published The Symbol Sourcebook, A Comprehensive Guide to International Graphic Symbols. This visual database of over 20,000 symbols continues to provide a standard for industrial designers around the world.

Death

On October 5, 1972, Dreyfuss and his terminally-ill wife and business partner Doris Marks Dreyfuss committed suicide by running their car in the garage of their South Pasadena, California home. Dreyfuss was survived by a son and two daughters.[6][7][8]

References

Notes

- Stoddard, Bill. "Westclox Big Ben and Baby Ben Advertising History". ClockHistory.com.

- Drury, George H. (1993). Guide to North American Steam Locomotives. Waukesha, Wisconsin: Kalmbach Publishing Company. p. 271. ISBN 0-89024-206-2.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot & Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- "Designer of 1960s American Airlines logo tells Businessweek what he really thinks of AA's new logo". Sky Talk. Archived from the original on 2017-09-15. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- Henry Dreyfuss Associates | People | Collection of Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum

- JONES, ROBERT A. (7 May 1997). "Our Dreyfuss Affair". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- "Henry Dreyfuss, Noted Designer, Is Found Dead With His Wife". The New York Times. South Pasadena, CA. 6 October 1972. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- "Henry Dreyfuss". www.academystamp.com. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

Bibliography

- Dreyfuss, Henry. Symbol Sourcebook: An Authoritative Guide to International Graphic Symbols. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1984. ISBN 0-471-28872-1

- Dreyfuss, Henry. Designing for People. Allworth Press; illustrated edition, 2003. ISBN 1-58115-312-0

- Flinchum, Russell. Henry Dreyfuss, Industrial Designer: The Man in the Brown Suit. Rizzoli, 1997. ISBN 0-8478-2010-6

- Innes, Christopher. Designing Modern America: Broadway to Main Street. Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-300-10804-4

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Dreyfuss. |