Helping behavior

Helping behavior refers to voluntary actions intended to help the others, with reward regarded or disregarded. It is a type of prosocial behavior (voluntary action intended to help or benefit another individual or group of individuals,[1][2] such as sharing, comforting, rescuing and helping).

Altruism is distinguished from helping behavior. Altruism refers to prosocial behaviors that are carried out without expectation of obtaining external reward (concrete reward or social reward) or internal reward (self-reward). An example of altruism would be anonymously donating to charity.[3]

Perspectives on helping behavior

Kin selection theory

Kin selection theory explains altruism in an evolutionary perspective. Since natural selection aids in screening out species without abilities to adapt the challenging environment, preservation of good traits and superior genes are important for survival of future generations (i.e. inclusive fitness).[4][5] Kin selection refers to the tendency to perform behaviors that may favor the chance of survival of people with similar genetic base.[6][7][8]

W. D. Hamilton has proposed a mathematical expression for the kin selection:

- rB>C

"where B is the benefit to the recipient, C is the cost to the altruist (both measured as the number of offspring gained or lost) and r is the coefficient of relationship (i.e. the probability that they share the same gene by descent)."[9]

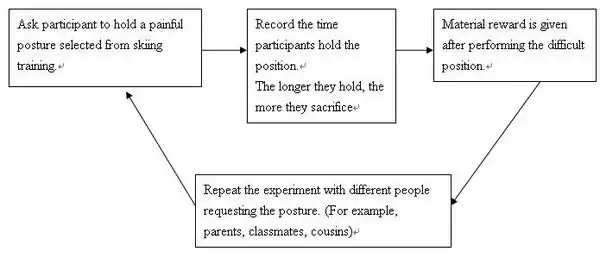

An experiment conducted in Britain supports kin selection[9] The experiment is illustrated by diagrams below. The result shows that people are more willing to provide help to people with higher relatedness and occurs in both gender and various cultures. The result also show gender difference in kin selection which men are more affected by the cues of similar genetic based than women.

Reciprocal altruism

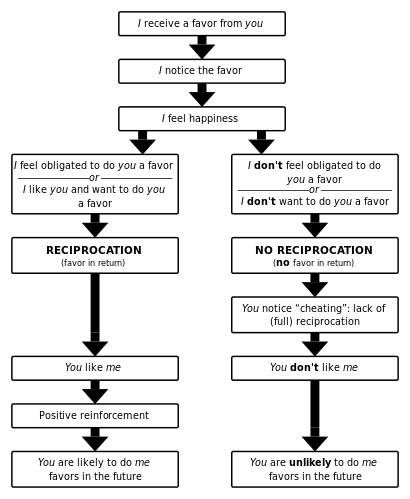

Reciprocal altruism is the idea that the incentive for an individual to help in the present is based on the expectation of the potential receipt in the future.[10] Robert Trivers believes it to be advantageous for an organism to pay a cost to his or her own life for another non-related organism if the favor is repaid (only when the benefit of the sacrifice outweighs the cost).

As Peter Singer[11] notes, “reciprocity is found amongst all social mammals with long memories who live in stable communities and recognize each other as individuals.” Individuals should identify cheaters (those who do not reciprocate help) who lose the benefit of help from them in the future, as seen in blood-sharing in vampire bats.[12]

Trade in economic trades and business[13] may underlie reciprocal altruism in which products given and received involve different exchanges.[14] Economic trades follow the “I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine” principle. A pattern of frequent giving and receiving of help among workers boost both productivity and social standing.

Negative-state relief model

The negative-state relief model of helping[15] states that people help because of egoism. Egoistic motives lead one to help others in bad circumstances in order to reduce personal distress experienced from knowing the situation of the people in need. Helping behavior happens only when the personal distress cannot be relieved by other actions. The model explains also people's avoidance behavior from people in need: this is another way of reducing distress.

Supporting studies

1) Guilt feelings were induced to subjects by having participants accidentally ruin a student's thesis data or seeing the data being ruined. Some subjects experience positive events afterwards, e.g. being praised. Results show that subjects who experience negative guilt feelings are more motivated to help than those who had neutral emotion. However, once the negative mood was relieved by receiving praise, subjects no longer had high motivation in helping.[16]

2) Schaller and Cialdini[15] found that people who are anticipating positive events (listening to a comedy tape), will show low helping motivation since they are expecting their negative emotions to be lifted up by the upcoming stimulation.

Empathy-altruism hypothesis

Helping behavior may be initiated when we feel empathy for the person, that is, identifying with another person and feeling and understanding what that person is experiencing.[17][18]

According to the Empathy-altruism hypothesis by Daniel Batson (1991),[19] the decision of helping or not depends primarily on whether you feel empathy for the person and secondarily on the cost and rewards (social exchange concerns). It can be illustrated in the following diagram:

The hypothesis was supported by some studies. For example, a study conducted by Fultz and his colleagues (1986)[20] divided participants into a high-empathy group and a low-empathy group. They both had to listen to another student, Janet, who reported feeling lonely. The study found that high-empathy group (told to imagine vividly how Janet felt) volunteered to spend more time with Janet, whether or not their help is anonymous, which makes the social reward lower. It shows that if the person feels empathy, they will help without considering the cost and reward, and it complies with the empathy-altruism hypothesis.

Responsibility – prosocial value orientation

A strong influence on helping is a feeling of and belief in one's responsibility to help, especially when combined with the belief that one is able to help other people. The responsibility to help can be the result of a situation focusing responsibility on a person, or it can be a characteristic of individuals (leading to helping when activated by others' need). Staub has described a "prosocial value orientation" that made helping more likely both when a person was in physical distress and psychological distress. Prosocial orientation was also negatively related to aggression in boys, and positively related to "constructive patriotism". The components of this orientation are a positive view of human beings, concern about others' welfare, and a feeling of and belief in one's responsibility for others' welfare.[21]

Social exchange theory

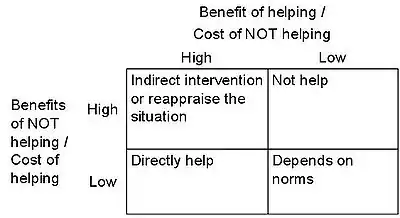

According to the social-exchange theory, people help because they want to gain goods from the one being helped.[22] People calculate rewards and costs of helping others, and aim at maximizing the former and minimizing the latter, which is known as a “minimax” strategy.

Rewards are incentives, which can be materialistic goods, social rewards which can improve one's image and reputation (e.g. praise) or self-reward.[23][24][25][26]

Rewards are either external or internal. External reward is things that obtained from others when helping them, for instance, friendship and gratitude. People are more likely to help those who are more attractive or important, whose approval is desired.[27][28] Internal reward is generated by oneself when helping, for example, sense of goodness and self-satisfaction. When seeing someone in distress, one would empathize the victim and are aroused and distressed. We may choose to help in order to reduce the arousal and distress.[29] Preceding helping behavior, people consciously calculate the benefits and costs of helping and not helping, and they help when the overall benefit of helping outweigh the cost.[30]

Implications

Cultural differences

A major cultural difference is the difference between collectivism and individualism. Collectivists attend more to the needs and goals of the group they belong to, and individualists focus on their own selves. With such contrast, collectivists would be more likely to help the ingroup members, but less frequent than individualists to help strangers.[31]

Economic environment

Helping is influenced by economic environment within the culture. In general, frequency of helping behavior is inversely related to the country economic status.[32]

Rural vs. urban area

The context influences helping behaviors. While there is a myth that small towns are "safer" and "friendlier", it has yet to be proven. In a meta-analytical study by Nancy Steblay, she found out that either extreme, urban (300,000 people or more) or rural environments(5,000 people or less), are that worst places if you're looking for help.[33]

Choosing a role

Edgar Henry Schein, former professor at MIT Sloan School of Management, assigns three different roles people follow when responding to offers of help. These generic helping roles are The Expert Resource Role, The Doctor Role, The Process Consultant Role.[34]

The Expert Resource Role is the most common of the three. It assumes the client, the person being helped, is seeking information or expert service that they cannot provide for themselves. For example, simple issues like asking for directions or more complex issues like an organization hiring a financial consultant will fall into this category.[35]

The Doctor Role can be confused with the Expert Role because they seem to overlap each other. This role includes the client asking for information and service but also demands a diagnosis and prescription. Doctors, counselors, coaches, and repair personnel fulfill this kind of role. Contrary to the expert role, the Doctor Role shifts more power to the helper who is responsible for the previously mentioned duties; diagnosing, prescribing, and administering the cure.[36]

Schein describes the Process Consultant Role where the helper focuses on the communication process from the very beginning. Before help can start, there needs to be an establishment of trust between the helper and the client. For example, in order for a tech consultant to be effective, he or she has to take a few minutes to discuss what the situation is, how often the problem occurs, what has been tried before, etc. before transitioning into the expert role or the doctor role.[37]

References

- Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The Roots of Prosocial Behavior in Children. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33771-2.

- Siegler, R. (2006). How children develop, exploring child development student media tool kit & Scientific American Reader to accompany how children develop. New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 0-7167-6113-0.

- Miller, P. A., Bernzweig, J., Eisenberg, N., & Fabes, R. A. (1991). The development and socialization of prosocial behavior. In R. A. Hinde, & J. Groebel (Ed), Cooperation and prosocial behaviour (pp. 54–77). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39999-8.

- Hamilton, W. D. (1964). The genetical evolution of social behavior. I, II. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7, 1–52.

- Hamilton, W. D. (1971) Selection of selfish and altruistic behavior in some extreme models. In J. F. Eisenberg & W. S. Sillon (Eds.), Man and beast: Comparative social behavior. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Hoffman, M. L. (1981) Is altruism part of human nature? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40(1), 121-137.

- Sober, E., & Wilson, D. S. (1998). Unto others: The evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Michael, F.C. (1984) Co-operative breeding by the Australian Bell Miner Manorina melanophrys Latham: A test of kin selection theory. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 14, 137-146.

- Madsen, E. A., Tunney, R. J., Fieldman, G.., Plotkin, H. C., Dunbar, R. I. M., Richardson, J., McFarland, D. (2007) Kinship and altruism: A cross-cultural experimental study. British Journal of Psychology, 98(2), 339-359.

- Trivers, Robert (1971) The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46, 35-56.

- Singer, Peter (1994). Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Wilkinson, G. S. (1984) ‘Reciprocal Food Sharing in the Vampire Bat’, Nature, 308, 181-184.

- Loch, C. H., & Wu, Y. (2007). "Behavioral Operations Management". Foundations and Trends in Technology, Information and Operations Management,1(3), 121-232.

- Kaplan, H., and Hill, K. (1985). Food Sharing among Ache Foragers: Tests of Explanatory Hypotheses. Current Anthropology, 26, 223–245.

- Fultz. J, Schaller.M, & Cialdini. R.B. (1988). Empathy, sadness and distress: Three related but distinct vicarious affective responses to anothers' suffering. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 312- 315.

- Cialdini, R. B., Darby, B. L., Vincent, J. E. (1973). Transgression and altruism: a case of hedonism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(6), 501-516.

- Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., Akert. R.M. (1997). Social Psychology (2nd Ed.). The US: Addison-Ewsley Educational Publishers Inc.

- Gilovich, T., Keltner, D. & Nisbett, R.E. (2006) Social Psychology. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Batson, C.D., & Shaw, L.L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2,107-122.

- Fultz, J., Batson, C.D., Fortenbach, V.A., McCarthy, P.M., & Varney, L. (1986). Social evaluation and the empathy altruism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,50,761-769.

- Staub, Ervin (2003). The psychology of good and evil: What leads children, adults and groups to help and harm others. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 592. ISBN 0-521-52880-1.

- Foa, U. G., & Foa, E. B. (1975). Resource theory of social exchange. Morrisontown, N.J.: General Learning Press.

- Campbell, D. T. (1975). On the conflicts between biological and social evolution and between psychology and moral tradition. American Psychologist, 30, 1103–1126.

- Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998). Evolution of indirect reciprocity by image scoring. Nature, 393, 573-576.

- Nowak, M. A., Page, K. M., & Sigmund, K. (2000). Fairness versus reason in the ultimatum game. Science, 289, 1773–1775.

- Gilovich, T., Keltner, D. & Nisbett, R.E. (2006). Social Psychology. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Krebs, D. (1970). Altruism—An examination of the concept and a review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 72, 258-302.

- Unger, R. K. (1979). Whom does helping help? Paper presented at the Eastern Psychological Association convention, April.

- Piliavin, J. A., & Piliavin, I. M. (1973). The Good Samaritan: Why does he help? Unpublished manuscript, University of Wisconsin

- Myers, D. G. (1999). Social psychology. (6th ed.). United States of America: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- Triandis, H. C. (1991). Cross-cultural differences in assertiveness/competition vs. group loyalty/cooperation. In R. A. Hinde, & J. Groebel (Ed), Cooperation and prosocial behavior (pp. 78–88). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Levine, R. V., Norenzayan, A., Philbrick, K. (2001) Cross-cultural differences in helping strangers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 543-560.

- Steblay, N. M. (1987). Helping behavior in rural and urban environments: A meta-analysis. Psychology Bulletin, 102, 346-356.

- Schein, Edgar H. (2009). Helping : how to offer, give, and receive help (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Pub. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1-57675-863-2.

- Schein, Edgar H. (2009). Helping : how to offer, give, and receive help (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Pub. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-1-57675-863-2.

- Schein, Edgar H. (2009). Helping : how to offer, give, and receive help (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Pub. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-1-57675-863-2.

- Schein, Edgar H. (2009). Helping : how to offer, give, and receive help (1st ed.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Pub. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-1-57675-863-2.