Harriman station (Erie Railroad)

Harriman Station, formerly known as Turners Station until 1910, was the first station on the Erie Railroad Main Line west of Newburgh Junction in Harriman, New York. Built adjacent to Grove Street in Harriman, one of the earlier structures built here in 1838 was a three-story hotel-train station combination. This station caught fire in 1873 and was replaced by a one-story wooden structure. That structure remained in use for decades before it began decaying and was replaced in 1911 with a new station on land donated by the widow of Edward Henry Harriman. A new one-story structure was built on the land. The station was maintained as a one-story depot with an adjacent monument dedicated to the work of Charles Minot. Minot was a director of the Erie Railroad who, in 1851, while his train was stopped at Turner, made the first railroad call by telegraph.

Harriman | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

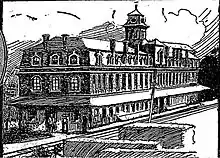

New Harriman station depot, seen in 1911 in a photograph by James E. Bailey, the Erie's official photographer and dispatcher from Meadville, Pennsylvania. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Grove Street, Harriman, New York | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 41°18′33″N 74°08′43″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owned by | Erie Railroad (1838 – 1960) Erie-Lackawanna Railway (1960 – 1976) Conrail (1976 – 1999) Norfolk Southern Railroad (1999 – 2006) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line(s) | Erie Railroad Main Line | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platforms | 1 side platform | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tracks | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Platform levels | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Station code | 2539[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | 1838 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Closed | April 18, 1983 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rebuilt | 1873; 1911 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Previous names | Turner (1838 – 1910) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former services | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The station depot remained in use by the Erie through October 1960, when that was folded into the Erie-Lackawanna Railroad, which itself would fold in April 1976, as it was absorbed into the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail). Conrail maintained passenger services until 1983 when that job was taken over by Metro-North Railroad. On April 18, 1983, the last passenger train left the Harriman station, as Conrail and Metro-North abandoned the tracks in favor of using the Graham Line (a high-speed freight line) for passenger and freight service. At that time, a new park & ride off of New York State Route 17 in Harriman opened for the newly realigned passenger service along the ex-Graham Line.

By the time that passenger service was transitioned to the Graham Line, the Harriman depot had been neglected for decades. The station depot remained on its concrete platform when the tracks were torn up on the old mainline. In 1996, workers removed the plaque attached to the Minot monument, but it was soon returned. However, the plaque was stolen shortly afterward and has not been recovered. The station depot itself was left in a decrepit condition as a result of the deterioration of its tiled roof. In 2006, the village of Harriman's building inspector ordered Norfolk Southern Railroad (the successor to Conrail and who owned the right-of-way) to either restore the building or demolish it. Norfolk Southern followed through with a demolition permit and in May 2006, the station depot was demolished by a front loader. The station remains were taken to a dump in Hillburn, New York.

History

First station constructed

The first station in Harriman, New York, then known as Turner, was first constructed around 1838 by Peter Turner, as one of the many stretches of the New York and Lake Erie Railroad was constructed through the town. The station itself was a 400 feet (120 m) long brick depot, three stories tall, and topped with a French roof. The station sat alongside the railroad tracks and was called the Orange Hotel.[2] The dining room of the new structure was able to hold 500 people at a time and accommodate them with good food.[3] During the planning of the Erie, there was some concern to whether or not the railroad would work its way through Harriman at all, instead of bypassing nearby Goshen and Middletown in favor of a terminus at Newburgh, also on the Hudson River.[4] Train service to Harriman began in 1841, when the New York and Lake Erie ran its first trains on June 30, 1841, from Piermont-on-Hudson, the determined eastern terminus, to Goshen, the western end.[5]

Construction progressed on the Erie Railroad, and by the end of 1841, grading from Middletown to Goshen was in progress and 410 of the 447 miles (719 km) chartered for the new railroad was contracted. The railroad had been running trains on the 46 miles (74 km) railroad line, carrying about 250 passengers per day. The new railroad was completed in April 1851 at its intended length to Dunkirk on Lake Erie.[6] On May 12, 1851, just about a month after the completion, a completion gala was held from Washington D.C.. Then-president Millard Fillmore and several members of his cabinet, along with several former governors of New York, attended. Several other distinguished individuals came from around the United States. On May 14, the tour arrived in New York City and began their trip on the first 447 miles (719 km) ride at Piermont at 7:45 that morning. The Fillmore train arrived at Dunkirk just past 4:00 pm the next afternoon.[7]

Charles Minot and the telegraph

In 1847, Ezra Cornell of Ithaca, New York worked to expand telegraphic communication through the New York and Lake Erie Railroad right-of-way with the Western Union Telegraph Company,[8] saving a telegraph line he built from New York City to Fredonia.[9] The new telegraph was an instant hit and was commonly used for gossip and casual chatting.[10] The then-superintendent of the New York and Lake Erie, Charles Minot, looked to expand this new technology with the railroad. He developed a system using telegraphs for train dispatches, for use when trains would want to pass one another along the line, such as at stations. Two-letter telegraph codes were designated, and the new modern system was set up. For the ten years of the new railroad's existence, passengers had been disgusted as trains waited for hours as another train had to pass them. This new system would relieve this issue.[11]

On September 22, 1851, Minot was in a parked passenger train at Turner Station. He glanced out the window of the train and saw the new telegraph wires. Departing the train, Minot ran into the station, got on the new telegraph, and wired the next station along the line, Monroe, to see if the eastbound train to Piermont-on-Hudson had gone past. The station agent said no. At that point, Minot ordered the engineer of the train to proceed on their way to Goshen.[11] The engineer refused to take Minot's order, and instead, Minot got into the cab car himself and drove the train himself to Port Jervis, hours ahead of the planned scheduled time of arrival.[12] This was the second of the several "firsts" the Erie Railroad created in its time, along with the shipment of milk by rail at Chester station in 1842.[13] The use of the telegraph and Minot's system remained until 1888, when a new system of block signaling, developed by the competitor Pennsylvania Railroad, helped expand Minot's use of telecommunications to control rail traffic.[11]

Naming controversy

Around 6:30 pm on the evening of Friday, December 26, 1873, the three-story Orange Hotel station depot caught fire. Some staff of the re-christened Erie Railroad were examining a room in the roof of the building, and upon looking into it, found it engulfed in smoke. The fire quickly spread, consuming the entire story. There was a lull, but the building re-ignited as flames continued through the building. The Mansard roof on top of the building was destroyed by the flames. No fire-ridding materials to douse the blaze were available to staff and no one could get near the building to inspect where the flames were. The flames finally destroyed the entire building, and just two hours after the fire was discovered, the walls began to collapse on the structure. Within a half-hour, the entire hotel/depot had collapsed and was a pile of brick ruins. Train service on the Erie mainline was disrupted for several hours due to the fire and station depot collapse.[2] A later study determined the station depot burned down due to a defective flue.[3]

The station depot was replaced by a wooden one-story depot, referred to by locals as a shack, along the side of the tracks in downtown Turner.[3] The new station itself lasted around the same amount of time that its predecessor station depot had; however, the widow of Edward Henry Harriman (d. September 9, 1909[14]), a local railroad executive whose Arden estate was in the nearby hills, donated land in February 1910 in a different portion of Turner to build a brand new station to the east.[15] The old one-story depot had a roof and structural supports that were aging and on the verge of collapsing to the ground.[16]

Plans for a new station didn't come without controversy though, as, in 1910 with the death of E.H. Harriman, there was a proposal by the Turner Village Improvement Association to rename the borough from Turner to Harriman as an honor to the late executive. On May 25, 1910, the association voted 58 to 13 to change the name. Harriman's widow said if they changed the name, she'd donate $25,000 (1910 USD, equivalent to $686 thousand in 2021) to help improvement the look and design of the village and $6,000 (1910 USD, equivalent to $165 thousand in 2021) more for a brand-new railroad station. It was proposed that by having the Erie Railroad change the station name on the decrepit depot from Turner to Harriman, the local Post Office would adopt the new name almost immediately. Erie conductors were told upon approaching Turner station to call the name Harriman. However, a local priest at the forefront of the controversy, Father McAran, thought the entire situation regarding the train from New York was a joke. To add to the annoyance of the priest, the old sign attached to the 1873 depot was replaced by a brand new one saying "Harriman".[17]

On the morning of May 26, the Erie Railroad sent a statement out from Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City, New Jersey to disregard the order from the previous day. The new sign came down instantly and the conductors continued to call the station Turner once again. Old-time locals felt the name Turner had more value to them and shouldn't be touched. A self-appointed committee run by the priest proposed a meeting on Saturday, June 4, 1910, at nearby Gillette Hall to protest the name change. The priest also offered that if the name was to remain Turner's, he would contribute $500 towards the construction of a new station. The post office also said they would remain named Turner even if the signage on the Erie Railroad station went back to the Harriman name.[17] Sometime during the night between June 1 and June 2, the Erie Railroad took the station depot sign for Turner down once again and re-attached the Harriman sign to the station depot. Local resolutions were sent to the Erie showing citizens' displeasure at changing the signage once again.[18] The order from the Erie stated that beginning on July 15, the station name would remain "Harriman" permanently. Father McAran returned to his outrage and continued to go to the press and give interviews on the issue at hand. To wrap the issue up, a sign in the front of the local church proclaiming "LONG LIVE TURNER" was destroyed. This hurt the enthusiasm of locals, who suggested renaming the local Arden station near the Harriman estate instead.[3]

New station opens at "Harriman"

A year after the great naming controversy and the station permanently being established as Harriman, construction began on a new station to replace the "disgraceful shack" that residents called Harriman.[3] That year a new station, built with the $6,000 from Edward Henry Harriman's widow, was constructed of brick with a stucco outlier. The roof of the one-story depot was built with shingles, which helped it match the Tudor-style used at the Tuxedo station eleven miles eastbound. The station, which was grounded on a large and wide concrete platform that also served as the new station platform, was built on Grove Street and had measurements of 20' x 26.5' x 19', common for a Type-9 Erie Railroad station design.[19] Just a year after the new station depot opened, the Erie honored the late Charles Minot on May 2, 1912, at the new station with a large ceremony attend by Mrs. Harriman, Erie president Frederick Underwood, several relatives to Minot, and other distinguished guests. At the ceremony, Minot's assistance to the railroad community was honored and a bronze tablet on a stone backing was unveiled as a monument to him.[20]

At this point, the Erie Railroad continued on with a new station at Harriman, which remained prosperous for years to come. The station featured both the main depot as well as a small shelter on the opposite side of the double-tracked line. In June 1931, James Gorney, a resident of Pine Island, allegedly attempted to rob the station and station agent. Harriman police shot Gorney in the leg, which was crippling enough that it required amputation of the leg. His lawyer, who got him off third-degree burglary charges and several acquittals, also negotiated a payment of $20,000 to Gorney from Harriman for the pain and suffering of the amputated leg, despite the attempted crime he was shot for. The jury deliberated for five hours before reaching a verdict of awarding Gorney the money.[21]

By the 1930s, long-distance passenger trains to Chicago, such as the Erie Limited and the Lake Cities, ran through Harriman but made no stops. Passengers would need to take a local train to Goshen or Middletown to transfer to the long-distance trains.[22]

End of service and demolition

Over the ensuing decades, the Erie Railroad fell into debt along with its competitor, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. On September 16, 1960, the Interstate Commerce Commission approved the railroads to go forward with a merger, creating the new Erie-Lackawanna Railroad on October 15, 1960.[23] The new railroad lasted only 16 years. In 1976, the Erie Lackawanna and several other large railroad companies were merged into the newly formed federal Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail).[24] At this point, stations had to fight for survival.[25] The station depot at Harriman has been closed and boarded up since at least 1970.[19] Passenger train service, however, remained intact through the early 1980s.[26]

In 1983, the station was finally closed when Conrail and the newly formed Metro-North Railroad announced that the new stations along the Erie's former high-speed freight line, the Graham Line, would take over freight and passenger service. Trains to Harriman would stop at a new park-and-ride built to the south.[27] The former 1911 station depot, however, remained standing until 2006, when the Harriman village building inspector forced the new owners of the right-of-way for the old mainline, Norfolk Southern, to either revamp or demolish the former station depot. The railway chose the latter, and in May 2006, an excavator tore down the 1911 depot, with the remains were taken to a dump in nearby Hillburn.[28]

See also

References

- "List of Station Names and Numbers". Jersey City, New Jersey: Erie Railroad. May 1, 1916. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- "Fire at Turner's Station N.Y." (PDF). The New York Times. December 27, 1873. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- "Village Rebels Over Being Rechristened "Harriman"" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York: Time Warner. June 12, 1910. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- Hungerford 1946, p. 29.

- Hungerford 1946, p. 59.

- Hungerford 1946, p. 63.

- Hungerford 1946, pp. 112–116.

- Hungerford 1946, p. 92.

- Oslin 1999, p. 59.

- Hungerford 1946, pp. 92–93.

- Hungerford 1946, p. 93.

- Hungerford 1946, pp. 93–94.

- Yanosey 2006, p. 19.

- "Edward Henry Harriman Dies at Arden After Long Illness". The Wall Street Journal. New York, New York: News Corporation. September 10, 1909. p. 20. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- "Mrs. Harriman Builds a Road" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York: Time Warner. February 26, 1910. p. 7. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- The Next Station Will Be.... - Port Jervis, Susquehanna, Scranton. East Hanover, New Jersey: Railroadians of America. 1982.

- "Turner Folk Oppose New Name Harriman" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York: Time Warner. May 29, 1910. p. 7. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- " "Turner" Again "Harriman"" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York: Time Warner. June 2, 1910. p. 20. Retrieved February 7, 2011.

- Yanosey 2006, p. 17.

- "Dedication of Historic Monument on Erie Railroad". Railway and Locomotive Engineering (June 1912): 199. June 1912. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- "Jury Gives $20,000 to "Jim" Gorney". The Newburgh News. November 4, 1935. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- 'Official Guide of the Railways,' August 1936, Erie Railroad section, Tables 2, 3

- "Erie and D, L & W to Merge October 15". The New York Times. September 16, 1960. p. 1.

- "Conrail Begins an Expensive Trip". The Milwaukee Journal. April 1, 1976. p. 43. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- Yanosey 2006, p. 3.

- Rider Guide Map. Newark, New Jersey: New Jersey Transit. 1980.

- "New Port Jervis Service - April 18, 1983". New York, New York: Metro-North Railroad. April 18, 1983. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- Yanosey 2006, p. 128.

Cited books

- Hungerford, Edward (1946). Men of Erie. Kingsport, Tennessee: Random House. OCLC 500324.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oslin, George P. (1999). The Story of Telecommunications. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-659-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yanosey, Robert J. (2006). Erie Railroad Facilities (In Color). Volume 2: New York. Scotch Plains, New Jersey: Morning Sun Books Inc. ISBN 1-58248-196-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-136, "Erie Railway, Harriman Station"