Haddington line

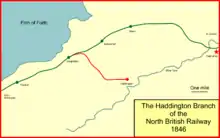

The Haddington line was a branch railway line connecting the Burgh of Haddington to the main line railway network at Longniddry. It was the first branch line of the North British Railway, and opened in 1846. Road competition severely hit passenger carryings in the 1930s, and the line closed to passengers in 1949. Coal and agricultural goods traffic continued, but the line closed completely in 1968.

Haddington Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

First railways

As early as 1825 the notion of a railway network covering much of central Scotland was being formed, but the cost of forming the line, and the limitations of the technology of the time, resulted in the scheme being shelved. In March 1836 a prospectus for a proposed Edinburgh, Haddington and Dunbar Railway was issued. The promoters had examined alternative routes to reach Dunbar; a coastal route (close to the present-day main line) was far easier to construct and operate, but the Garleton Hills lay between the coast and Haddington. Routing through the town generated more traffic, but it involved much more complex engineering, and would involve steep gradients that were challenging to the motive power of the period.[1]

The Edinburgh, Haddington and Dunbar Railway did not proceed, but later in 1836 a proposed Great North British Railway was put forward. This had the alternate title of Edinburgh, Dunbar, Berwick and Newcastle Railway, and it was designed to follow the coastal route. Dismayed at seeing their town omitted, the Burgh magistrates commissioned the railway engineer George Stephenson to report on the practicability of a route serving their town. His report of September 1838 was cursory, but noted that such a route would cost £100,000 more than the coastal route; he considered that an additional £5,000 per annum required to pay off that excess would be generated by the additional traffic from Haddington.

In 1838 the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway was authorised to build its main line; it opened in 1842. Now the attention of business people in Scotland turned to the construction of trunk railways, particularly a line to connect central Scotland with the English network which was taking shape. The possibilities, and the claimed advantages of rival routes, caught the public imagination, and there was much controversy over the line to be adopted; for some time it was assumed that only one line south could be viable commercially, and that selection of the line was a matter for Government, and a Commission (colloquially referred to as The Smith and Barlow Commission) was set up to do so. In fact the Commission's report was not decisive, and in January 1842 the promoters involved with the Great North British Railway decided to proceed with their own scheme for a railway from Edinburgh to Dunbar, again following the coastal route. With aspirations later to connect to England, they settled on the name "The North British Railway".[1]

The North British Railway board had not been unanimous in the decision, and a significant faction, led by Lord Tweeddale were insistent on going through Haddington. They were supported by the finding of the Smith and Barlow Commission, which had earlier condoned, in certain circumstances, the routing on the East Coast going through Haddington.[2]

The North British Railway

The representatives of Haddington were naturally disappointed with the route of the main line passing well to the north, and they induced the North British Railway promoters to reconsider. The NBR had a survey done for a branch line to Haddington, and for some this was not enough: only a main line would do. (A deputation from the Burgh gave mixed messages: they said that Haddington people did not want a railway at all, but if they must have one, then a main line would do less harm than a branch.)[3] At a tense meeting the NBR pointed out that the incremental cost of running via Haddington had been estimated at £116,000, while the entire authorised capital of the NBR was only £800,000; but if the town dropped its opposition, the NBR would "try to secure a branch line to Haddington". The NBR prospectus was issued with no mention of Haddington, but in November they indicated that a branch line was possible, at the expense of the NBR. The hawkish faction in the town was not satisfied: only a main line would be enough, and they would oppose the NBR Bill in Parliament. However wiser counsel prevailed, and the town accepted the inevitable and settled for a branch line, withdrawing their Parliamentary opposition on the understanding that their branch line would open on the same day as the main line. The North British Railway Act passed unopposed on 4 July 1844, with authorised capital of £800,000.[1][4][5][6][7]

The Haddington branch

The Haddington branch was therefore authorised; it was to be 4 miles 60 chains in length, leaving the future main line at Longniddry. The terminus at Haddington was to be half a mile short of the town centre. A contract for the construction was let on 27 September 1844 to James McNaughton and J Feely for £12,311.[1]

A rival line

There now followed an extraordinary episode in which a number of proposed railways together threatened the prosperity of the uncompleted North British main line and branch. In 1844 - 1845 there had been a sudden easing of the money market at the same time as the realisation that railway construction would make money, and numerous schemes were put forward. On 29 September the prospective East Lothian Central Railway issued a prospectus and invitation to subscribe for shares. With capital of £80,000 it was to build from the NBR Haddington terminus north-eastward to the NBR at East Linton, forming with the NBR, a through route from Edinburgh to Dunbar via Haddington. The line was to

afford the advantages of Railway communication to the rich agricultural and mineral districts in the centre of Haddingtonshire, for which no provision has hitherto been made. It will connect Haddington, the County Town, by a direct line with East Linton, and the important seaport of Dunbar... Dunbar is, by the North British Railway [now in progress] 22 miles from the County Town, while, by this line, it will be 11, or just one half the distance... In this way a complete through line will be formed... shorter than the present line of the North British Railway by about a mile and a half; and in this way a considerable portion of the through traffic of that line must be immediately secured...

The direct connection to Dunbar was of course to be over the NBR from East Linton. George Stephenson's 1836 survey was misrepresented:

Mr George Stephenson... recommended the proposed Line in preference to that which has been adopted by the North British Railway... [The line] will, on the one hand, transport the coal and limestone for the whole of the Eastern District of the County; while on the other, a large proportion of the grain and other farm produce sold at Haddington market weekly, will be sent along the line.[8]

When the Edinburgh, Portobello and Musselburgh Railway issued its prospectus (capital £200,000) a little later, it noted that "the present line of the North British Railway... is extremely circuitous, and otherwise quite inadequate..." It was to link up with yet another proposed railway: "The Committee have further had their attention directed to the great advantages likely to be derived from the formation of a branch to connect with the proposed Tyne Valley[note 1] Junction Railway, which would likewise secure for this line the whole direct traffic from Haddington."[9]

The Tyne Valley Junction Railway hoped to link Haddington and Dalkeith, and it would have a station in the centre of Haddington.[7]

The East Lothian Central Railway would of course have been entirely dependent on the good will of the North British in practice, but the NBR directors appear to have lost their nerve, for it was reported on 23 October that "The North British Company have, we understand, allied themselves to the East Lothian Central Company."[10]

The East Lothian Central and the Tyne Valley Junction merged, forming the East Lothian and Tyne Valley Railway (EL&TVR). The North British directors now agreed that the Dalkeith route would be the main line from Haddington to Edinburgh, the Longniddry line being merely a secondary route; and they undertook that the NBR would take shares in the EL&TVR to the value of £125,000, and pay £10,000 in cash to the EL&TVR. If necessary, the NBR would extend their branch line to terminate closer to the centre of Haddington.[7] Then in 1846 the money supply suddenly became very tight, and in March or April the EL&TVR suddenly ceased trading, and their threat to NBR traffic was removed.[1]

Opening

By May 1846 the line was ready to be inspected by Major-General Pasley, the Board of Trade Inspecting Officer, and on 22 June 1846 the North British Railway opened its lines, from the North Bridge station in Edinburgh to Berwick, and from Longniddry to Haddington. The station at Haddington was on the western margin of the town and a horse-omnibus connected with all the trains. The trains ran as far as Longniddry only: there were five each way on weekdays and two on Sundays, all of them mixed passenger and goods. Daily residential travel seems to have started from the outset, by the issue of season tickets to Edinburgh. There were intermediate public sidings at Laverocklaw and Coatyburn.[1][4][6]

A head-on collision on the single line was narrowly averted:

North British Railway—Disgraceful Negligence—On the Haddington branch of the North British Railway on Friday last [14 August 1846], as a train with passengers was coming up from the Longniddry station to Haddington (a single line)—what was the horror of the engineer when he perceived another train coming down at full speed! A concussion was thought impossible to avoid; however a stoppage was managed just in time to prevent any serious consequences, but, had there been a mist or fog, such as has occasionally prevailed during the week, the consequences must have been dreadful.[11]

Notwithstanding the limited train service the Directors decided to lay a second track, making double track on the line. This seems a remarkable extravagance; in fact the decision was reviewed in 1856: on 26 September one line of rails was ordered to be removed, and the work of singling the line was completed by 7 October 1856.[1][4]

Passenger carryings were very disappointing in the first years, but they grew steadily and by 1881 seven passenger trains ran daily each way, with an additional market train through to Edinburgh on Fridays.[1]

Jane Carlyle, a native of Haddington, used the line on a number of occasions in the 1850s. She found it less than satisfactory. In a letter to her husband dated 28 August 1857 she wrote:

"I left Edinburgh at two yesterday, was at Longniddry by half-past two, and didn't get to Haddington till four. Such complete misunderstandings exist between the little Haddington cross-train and all other trains, that one may lay one's account with having to wait always three-quarters of an hour at the least, Then the waiting-room is 'too stuffy for anything,' and the seated structure outside expressly contrived for catching cold in; so that one is fain to hang about on one's legs in space.",[12]

.

The original passenger terminal building at Haddington was basic, and in the 1880s a new and impressive building was provided. At the same time a considerable extension to the goods shed was built, together with enhanced facilities for cattle loading. Longniddry station was also poorly provided for; the down platform was lengthened in July 1894 and improved passenger accommodation was provided in 1898, in connection with the opening of the Gullane branch, which also used Longniddry as its junction station. The Down platform was made into an island, and the Haddington passenger trains used its outer face. In the twentieth century daily residential travel increased considerably, and through trains were run from Haddington to Edinburgh to accommodate it.

The twentieth century

In 1923 the railways of Great Britain were "grouped" under the Railways Act 1921; the North British Railway was a constituent of the new London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). In that and the following decade there was little change in the activity on the branch, but following the end of World War I road motor vehicles appeared in significant numbers and started abstracting business from the line. Road improvements followed:

Haddington Bye-Pass Road: Work has been commenced on the new bye-pass road for the town of Haddington. The cost of the scheme is estimated at £50,000, and the work is being proceeded with in order to alleviate unemployment... The new road will be nearly two miles in length, and provision is made for the erection of a new bridge over the Haddington branch of the London and North-Eastern Railway... This will be the third great improvement on the Berwick - Edinburgh Road, previous improvements being carried out at East Linton and the Tower Bridge.[13]

The bridge over the Haddington branch was made sufficient for double track, unlikely though it was that the line would once again be doubled. In fact the Great North Road, which became the A1, was progressively improved, and later in the 1930s buses started to run at fifteen-minute intervals, and motor lorries became popular carriers. By now there were no through trains to Edinburgh from Haddington (except the Friday market train) further worsening the railway's competitive position.

During World War II an army base at Amisfield and at RAF station at Lennoxlove brought military traffic to the branch. After the war the railways were nationalised in 1948, and the area became part of the Scottish Region of British Railways.

Loss of passenger and goods traffic to road operators continued to be a serious issue and the viability of the branch line was now in doubt. In fact in September 1949 it was announced that the branch would close to passengers. There was an outcry in Haddington, but it was stated by the Town Clerk that an average of three persons travelled in each train, notwithstanding the introduction of cheap tickets. It was obvious that any protest was hopeless and closure was announced for 5 December 1949.

Coal and cattle feed traffic kept the branch going for goods purposes, but that too steadily declined over the years and on 5 March 1968 only coal traffic continued for a few weeks, the branch closing completely on 30 March 1968.[1][4]

The railway sleepers and rails were lifted and the land occupied by the branch line purchased by East Lothian Council in 1978.[1] The old route of the branch line is at present used by walkers, cyclists, and horse riders. A section of the route inside the town between Gateside Road and Alderston Road is paved and used as a footpath.

Signalling

After the primitive signalling originally provided on the line, the train staff and ticket system was implemented by the 1860s. There were signalboxes at Longniddry and Haddington. In 1892 Tyers electric train tablet system was installed; the intermediate sidings at Coatyburn and Laverocklaw were accessed by ground frame released by the tablet. On 3 August 1952 the branch was converted to one engine in steam operation, and Haddington signal box was

Topography

From Longniddry the line climbed at 1 in 66 to the 2 1/2 mile post, slackening a little there to 1 in 80 as far as the 3 mile post. The line then fell at 1 in 80 to Haddington. There were intermediate sidings at Coatyburn, a little short of the 2 mile post, and Laverocklaw siding, at about 2 1/4 miles.

Remaining evidence of the railway line includes the original station building, Haddington station's platform, the station embankments on West Road / Somnerfield Court, and a series of stone bridges between Longniddry and Haddington. At least part of the old station platform at Coatyburn Sidings also remains. The most obvious remains of the branch is the physically cleared and levelled ground on which the railway line was constructed.

Future scope

There is a campaign to reopen Haddington’s railway service led by the group RAGES (Rail Action Group East of Scotland). Most of the 4.8 mile stretch of the Haddington line is unoccupied; however at the eastern terminus in Haddington there are industrial units occupying the station's old location. This means that either the industrial units must be moved or a new location for the branch's terminus be found. There are additional problems regarding where the A1 dual-carriageway crosses over the old branch line; for here the branch line is obliterated by a modern road. A further problem for reopening the line lies with congestion on the East Coast Main Line at peak hours, as well as at Edinburgh Waverley station, where the old east-bound platforms are now (with the exception of North Berwick's platform) occupied by a modern building within the Victorian station. One possible way of averting these problems would be for carriages from Haddington to join trains from North Berwick (at Longniddry) - made possible by North Berwick having electrically powered carriages. It remains to be seen whether the campaign by RAGES will win the support of Transport Scotland or the Scottish Government.

Notes

- Not the Northumberland Tyne, but the Haddington Tyne, flowing from Pencaitland through Ormiston, Haddington and East Linton, and running into the Firth of Forth at West Barns.

References

- Hajducki, Andrew M. (1994). The Haddington, Macmerry and Gifford Branch Lines. Oxford: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-456-3.

- Robertson, C.J.A. (1983). The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 - 1844. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-85976-088-X.

- Ross, David (2014). The North British Railway: A History. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84033-647-4.

- Thomas, John (1984). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 6, Scotland, the Lowlands and the Borders. revised by J.S. Paterson. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-946537-12-7.

- Carter, E.F. (1959). An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles. London: Cassell.

- Smith, W.A.C.; Anderson, Paul (1995). An Illustrated History of Edinburgh's Railways. Caernarfon: Irwell Press. ISBN 1-871608-59-7.

- Thomas, John (1969). The North British Railway, volume 1. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4697-0.

- "Prospectus of the East Lothian Central Railway". Caledonian Mercury. 29 September 1845 – via Newspapers.com.

- Liverpool Mail. 18 October 1845. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Stirling Observer. 23 October 1845. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Stirling Observer. 20 August 1846. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Froude, J.A., ed. (1883). The Letters and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle, Vol. II. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Berwickshire News and General Advertiser. 10 June 1930. Missing or empty

|title=(help)