HIV/AIDS in Australia

The history of HIV/AIDS in Australia is distinctive, as Australian government bodies recognised and responded to the AIDS pandemic relatively swiftly, with the implementation of effective disease prevention and public health programs, such as needle and syringe programs (NSPs). As a result, despite significant numbers of at-risk group members contracting the virus in the early period following its discovery, the country achieved and has maintained a low rate of HIV infection in comparison to the rest of the world.

At the end of 2017, 27,545 people were estimated to be living with HIV in Australia. 20,922 infections were attributable to male‐to‐male sex exposure, 6,245 to heterosexual sex, 605 to injecting drug use, and 168 to ‘other’ exposures (vertical transmission to newborn, blood/tissue recipient, healthcare setting, haemophilia/coagulation disorder).[1] AIDS is no longer considered an epidemic or a public health issue in Australia, due to the success of anti-retroviral drugs and extremely low HIV-to-AIDS progression rates.[2]

The first Australian case was in 1981 and this was diagnosed retrospectively in 1994 in an article by Dr Paul Gerrard published in the Medical Journal of Australia (Australia's first case of AIDS?: Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and HIV in 1981). Further cases of HIV/AIDS were in Sydney in October 1982, and the first Australian death from AIDS occurred in Melbourne in July 1983.[3][4][5]

Spurred to action both by the emergence of the disease amongst their social networks and by public hysteria and vilification, gay, lesbian, drug user and sex worker communities and organisations were instrumental in the rapid creation of AIDS councils (though their names varied), sex worker organisations, drug user organisations and positive people's groups. The AIDS councils were formed in South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia in 1983, and in New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory in 1985.[3][6][7][8][9] The state and territory AIDS councils, along with the other national peak organisations representing at-risk groups Australian Injecting & Illicit Drug Users League (AIVL), National Association of People with HIV Australia (NAPWHA), Anwernekenhe National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander HIV/AIDS Alliance (ANA), the Scarlet Alliance, and the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, all contribute to Australia's response to HIV.[10]

Non-governmental organisations formed swiftly and have remained prominent in addressing AIDS in Australia. The most notable include the AIDS Trust of Australia, formed in 1987,[11] The Victorian AIDS Council (VAC),[12] formed in July 1983, and the Bobby Goldsmith Foundation, founded in mid 1984. The Bobby Goldsmith Foundation is one of Australia's oldest HIV/AIDS charities.[13] The Foundation is named in honour of Bobby Goldsmith, one of Australia's early victims of the disease, who was an athlete and active gay community member, who won 17 medals in swimming at the first Gay Olympics, in San Francisco in 1982.[14] The Foundation had its origins in a network of friends who organised care for Goldsmith to allow him to live independently during his illness, until his death in June 1984. This approach to supporting care and independent living in the community is the basis of the Foundation's work, but is also an approach reflected in the activities and priorities of many HIV/AIDS organisations in Australia.

In 1985, Eve van Grafhorst was ostracised since she had contracted HIV/AIDS caused by a transfusion of infected blood.[15] The family moved to New Zealand where she died at the age of 11.

Australian responses to HIV/AIDS

The Australian health policy response to HIV/AIDS has been characterised as emerging from the grassroots rather than top-down, and as involving a high degree of partnership between government and non-government stakeholders.[16] The capacity of these groups to respond early and effectively was instrumental in lowering infection rates before government-funded prevention programs were operational.[17][18] The response of both governments and NGOs was also based on recognition that social action would be central to controlling the disease epidemic.[19]

In 1987, a well-known advertising program was launched, including television advertisements that featured the grim reaper rolling a ten-pin bowling ball toward a group of people standing in the place of the pins. These advertisements garnered a lot of attention: controversial when released, and continuing to be regarded as effective as well as pioneering television advertising.[20][21]

The willingness of the Australian government to use mainstream media to deliver a blunt message through advertising was credited as contributing to Australia's success in managing HIV.[22] However the campaign also contributed to stigma for those living with the disease,[23] particularly in the gay community, an impact one of the advertising scheme's architects later regretted.[24]

Australian Governments began in the mid-1980s to pilot or support programs involving needle exchange for intravenous drug users. These remain occasionally controversial, but are reported to have been crucial in keeping the incidence of the disease low, as well as being extremely cost-effective.[25][26]

HIV/AIDS quickly became a more severe problem for several countries in the region around Australia, notably Papua New Guinea and Thailand, than it was within Australia itself. This led Australian governments and non-government organisations to place an increasing emphasis on international initiatives, particularly aimed at limiting the spread of the disease. In 2000, the Australian government introduced a $200 million HIV/AIDS prevention program that was targeted at south-east Asia.[27] In 2004, this was increased to $600 million over the six years to 2010 for the government's international HIV/AIDS response program, called Meeting the Challenge.[28] Australian non-government organisations such as the AIDS Trust are also involved in international efforts to combat the illness.[29]

HIV/AIDS and Australian law

Deliberate or reckless transmission

In response to the risks of HIV transmission, some governments (e.g. Denmark) passed legislation designed specifically to criminalise intentional transmission of HIV.[30] Australia has not enacted specific laws, there have been a small number of prosecutions under existing state laws, with four convictions recorded between 2004 and 2006.[31]

The case of Andre Chad Parenzee, convicted in 2006 and unsuccessfully appealed in 2007, secured widespread media attention as a result of expert testimony given by a Western Australian medical physicist that HIV did not lead to AIDS.[31][32][33]

In February 2008, Hector Smith, aged 41, a male prostitute in the Australian Capital Territory who is HIV-positive, pleaded guilty in the ACT Magistrates Court to providing a commercial sexual service while knowing he was infected with a sexually-transmitted disease (STD) and failing to register as a sex worker.[34] Under ACT law it is illegal to provide or receive commercial sexual services if the person knows, or could reasonably be expected to know, that he or she is infected with a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

In January 2009 Melbourne man Michael Neal was jailed for 18 years (with a minimum term of thirteen years, nine months) for deliberately infecting and trying to infect sexual partners with HIV without their knowledge, despite multiple warnings from the Victorian Department of Human Services.[35]

Discrimination

Australian governments have made it illegal to discriminate against a person on the grounds of their health status, including having HIV/AIDS;[36] for example, see Disability Discrimination Act, 1992 (Cwlth). However HIV positive individuals may still be denied immigration visas on the grounds that their treatment takes up limited resources and is a burden for taxpayers.[37] To end HIV discrimination in Queensland and Australia in general, there is a plan to raise awareness and educate local people on HIV by 2020.[38] This program is supported by government, as well as by many educational and volunteer organizations. The main aim of the program is to educate people about HIV as it will help to prevent it and stop HIV discrimination in the area.

Blood donations

Australia was one of the first countries to screen all blood donors for HIV antibodies,[3] with screening in place for all transfused blood since March 1985.[39] This was not before infection was spread through contaminated blood, resulting in legal cases in the 1980s around whether screening had been appropriately implemented. One issue highlighted in the course of those actions was the challenge of medical litigation under statutes of limitation. A medical condition such as HIV that can lie latent or undiagnosed for a long period of time may only emerge after the time period for litigation has elapsed, preventing examination of medical liability.[40] Concerns about the integrity of the blood supply resurfaced following a case of the contraction of HIV by transfusion in Victoria in 1999. This led to the introduction of new blood screening tests, which also improved screening in relation to Hepatitis C.[41]

Gay men have sought to donate blood to help increase Australia's blood supply stock, saying this volunteering would, in turn, help reduce discrimination towards LGBT people.[42][43] The Australian Red Cross Blood Service have indicated their concern regarding the possible transmission of HIV and noting they are receptive to a reduction in the current deferral period from 12 to 6 months, but the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration, has rejected their submission on this issue.[44]

HIV/AIDS and Pregnant Australian Women

By the end of 2017, there were estimated to be 3,349 women diagnosed with HIV comprising 13.8% of all infections.[1] In 2013, the median age of diagnosis for women is at 30 years of age. The reasons for acquiring the HIV blood test is spread across three circumstances. Firstly, 30.2% of people become physically ill, 17.1% of peoples partner had tested positive therefore they accessed medical assistance and thirdly, 12.9% of people acquired testing due to exposure to a large risk episode.[45]

Contracting HIV/AIDS

The most common form of transmissions of HIV is through blood, semen, pre-ejaculation, rectal mucus, vaginal fluids and breast milk. Therefore, women need to be extremely cautious when engaging in sexual activity as well as if and when falling pregnant.[46] Often, behaviours that lead to women contracting the HIV virus include engagement in sexual intercourse within a heterosexual relation with someone who already has HIV/AIDS, using drugs intravenously or receiving infected blood products.[45]

Pregnant while HIV-positive

| stage | starts | ends |

|---|---|---|

| Preterm | at 37 weeks | |

| Early term | 36 weeks | 39 weeks |

| Full term | 39 weeks | 41 weeks |

| Late term | 41 weeks | 42 weeks |

| Postterm | 42 weeks | |

Risks of passing on the HIV virus to an unborn child is extremely high for women whom have been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS. In Australia, it is a part of routine antenatal testing that mothers undergo a blood test to check for HIV/AIDS.[48] HIV transmission to an unborn child is often called Perinatal HIV transmission, Vertical Transmission or Mother-To-Child-Transmission (MTCT).[49] There are three main ways a mother can risk passing on the HIV virus to her child and that is during the pregnancy via crossing of the placenta, during birth if the baby comes in contact with the mothers bodily fluids and through the practice of breastfeeding.[48][49] Therefore, when falling pregnant it is important for a mother to access additional Antenatal care. Visitation to an infectious disease physician, experienced obstetrician, paediatrician and midwife is recommended. As well as accessing additional psycho-social support such as a counselor and support worker.[49]

To reduce the risks of MTCT the mother can start preparing prenatally with a series of anti-retroviral medications. Using other means of conception practices such as the method of 'sperm washing'. This is where the sperm cells are separated from the seminal fluid and used to fertilise a woman's eggs via the use of a catheter or in vitro fertilisation (IVF) methods.[46] Seeking additional medical checkups to observe clinical markers determining disease progression along with regular observations of baby's development can also help in monitoring the health of the baby.[45][48]

In addition, the postnatal care taken to reduce risks of MTCT include avoiding procedures where the baby's skin may be cut or electing to have a cesarean section to reduce the risk of contact with body fluids.[49] Ensuring the baby's eyes and head are cleaned, the umbilical cord is clamped as soon as possible and placing an absorption pack (towel or sponge) over the umbilical cord when cut to prevent blood spurting will also reduce the risk of the baby coming in contact with any contaminated fluids.[49] Bottle feeding the baby also removes any chance of coming in contact with infected body fluids.[46] Along with the mother taking anti-retroviral medication, giving the baby a course of this until it is 4–6 weeks of age also drastically reduces its risk of transmission.[48] Medical practitioners also require the infant undergo regular blood tests at 1 week, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months, 12 months and 18 months to test for any evidence of the HIV virus.[48]

Stigma associated towards Women with HIV/AIDS

Association with HIV/AIDS within Australia is largely absent from the mainstream population. Therefore, in 2009, 73.6% of women diagnosed with HIV/AIDS reported unwanted disclosure of their health status due to a lack of awareness and knowledge about the disease.[45] This was due to the large amount of stigma associated with a HIV diagnosis. The emotional and psychological problems for pregnant mothers within Australia are extremely high. 42% of women diagnosed with HIV/AIDS are also diagnosed with a mental health condition due to the harsh effects of the arising stigma around such circumstances.[50] The stigma associated with HIV diagnosis in women often involves evoked assumptions that these women are considered a part of the sex trade industry, are homosexual or are intravenous drug users.[51] These women are often viewed as contagious and are assumed to have devious traits and behaviours. In western society, socially specific roles expected of women, such as motherhood, create automatic discrimination when diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.[45] Those women diagnosed with HIV/AIDS who express the idea of wanting to become pregnant are often discriminated against as being selfish, inconsiderate, uncaring and immoral.[51] Healthcare professionals and practitioners are often reported as having negative attitudes towards women who openly identify with having HIV/AIDS and being pregnant or wanting to become pregnant.[51]

Ongoing research and awareness-raising

The Sydney Mardi Gras, one of the largest street parades and gay and lesbian events in the world,[52] has HIV/AIDS as a significant theme, and is one of a number of pathways through which the non-government sector in Australia continues to address the disease.[53]

Australian researchers have been active in HIV/AIDS research since the early 1980s.[54] The most prominent research organisation is the Kirby Institute (formerly National Centre in HIV Epidemiology & Clinical Research), based at the University of New South Wales, regarded as a leading research institution internationally, and a recipient of one of the first grants of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation outside the United States.[55] The Centre focusses on epidemiology, clinical research and clinical trials.[56] It also prepares the annual national surveillance reports on the disease. In 2006 the Centre received just under A$4 million in Commonwealth government funding, as well as several million dollars of funding from both public and pharmaceutical industry sources.[57] Three other research centres are also directly Commonwealth funded to investigate different facets of HIV/AIDS: the National Centre in HIV Social Research (NCHSR); the Australian Centre for HIV and Hepatitis Virology Research (ACH2) (formerly the National Centre for HIV Virology Research); and the Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society (ARCSHS).

Research has identified anal mucus as a significant carrier of the HIV virus,[58] with the risk of HIV infection after one act of unprotected receptive anal sex being approximately 20 times greater than after one act of unprotected vaginal sex.[59] Anal sex, risk-reduction strategies have been identified and promoted to reduce the likelihood of transmission of HIV/AIDS.[60][61]

HIV/AIDS in Australia since 2000

While the spread of the disease has been limited with some success, HIV/AIDS continues to present challenges in Australia. The Bobby Goldsmith Foundation reports that nearly a third of people with HIV/AIDS in New South Wales (the state with the largest infected population) are living below the poverty line.[13] Living with HIV/AIDS is associated with significant changes in employment and accommodation circumstances.[62][63]

Survival time for people with HIV has improved over time, in part through the introduction of antiretroviral drug treatments[64] with post-exposure prophylaxis treatments reducing the possibility of seroconversion and minimising the likelihood of HIV progression to AIDS. However, HIV does have its own health issues.[65][66]

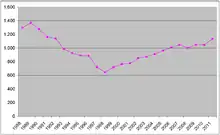

After the initial success in limiting the spread of HIV, infection rates began to rise again in Australia, though they remained low by global standards. After dropping to 656 new reported cases in 2000, the rate rose to 930 in 2005.[67] Transmission continued to be predominantly through sexual contact between men, in contrast to many high-prevalence countries in which it was increasingly spread through heterosexual sex.[67][68] Indeed, the majority of new Australian cases of HIV/AIDS resulting from heterosexual contact have arisen through contact with a partner from a high-prevalence country (particularly from sub-Saharan Africa or parts of south-east Asia).[69]

The new trend toward an increase in HIV infections prompted the government to indicate it was considering a return to highly visible advertising.[70] Reflecting this concern with the rise in new cases, Australia's fifth National HIV/AIDS Strategy (for the period 2005–2008) was titled Revitalising Australia's Response, and placed an emphasis on education and the prevention of transmission.[71]

On 19 October 2010, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that 21,171 Australians have HIV, with 1,050 new cases diagnosed in 2009. The Sydney Morning Herald also reported that 63% of Australians living with HIV were men who have sex with men (MSM), and 3% were injecting drug users.[72]

Infection rates in Australia

In 2017 it was estimated 27,545 people living with HIV in Australia. In 2017, 63% of HIV notifications were attributed to sexual contact between men. 25% of cases were attributed to heterosexual sex, 5% to a combination of sexual contact between men and injecting drug use, 3% to injecting drug use only, and 3% to other/unspecified.[73]

The Australian Federation of Aids Organisations reports that there has been a consistent decline in new HIV infections among men who have sex with men (MSM).[74]After peaking at 1,084 new diagnosed cases in 2014, the rate has dropped each year to reach 833 in 2018.[74] They estimate 6.3% of all MSM in Australia are living with HIV. While there has been a dramatic decrease in MSM with an 23% decline between 2014 and 2018, this has been partially offset by a 19% increase in case attributed to heterosexual sex during the same period.[74][1]

XX International AIDS Conference (2014)

From 20 to 25 July 2014, Melbourne, Australia hosted the XX International AIDS Conference. Speakers included Michael Kirby, Richard Branson and Bill Clinton. Clinton's focus was HIV treatment and he called for a greater levels of treatment provision worldwide;[75][76] in an interview during the conference, Kirby focused on legal issues and their relationship to medication costs and vulnerable groups—Kirby concluded by calling for an international inquiry:

And what is needed, as the Global Commission on HIV and the Law pointed out, is a new inquiry at international level – inaugurated by the secretary-general of the United Nations – to investigate a reconciliation between the right to health and the right of authors to proper protection for their inventions. At the moment, all the eggs are in the basket of the authors, and it's not really a proportionate balance. And that's why the Global Commission suggested that there should be a high level of investigation.[76]

Branson, Global Drug Commissioner at the time of the conference, stressed the importance of decriminalising illicit injecting drug use to the prevention of HIV and, speaking in global terms, stated that "we're using too much money and far too many precious resources on incarceration".[77] The Open Society Foundation launched the "To Protect and Serve How Police, Sex Workers, and People Who Use Drugs Are Joining Forces to Improve Health and Human Rights" report at the conference.[78]

The International AIDS Society (IAS) confirmed that six passengers on board the Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 shot down over Ukraine were killed. The six delegates were acknowledged during the conference at the AIDS 2014 Candlelight Vigil event.[77][79]

Antiretroviral treatments

HIV infection is now treatable for those with HIV expecting to live near-normal lifespans, providing they continue taking a regimen of antiretroviral drugs.[80] Post-exposure prophylaxis drugs are generally available in Australia at a subsidised cost through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS).[81] 84% of (the 24,000[82]) HIV positive gay men were on antiretroviral treatments in 2014.[83]

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) drugs[84] are used as a means of reducing HIV risk for people who do not have HIV, with some advocates saying it will allow condomless safe-sex.[85] Previously it costs $750 per month to import the drug from overseas.[86] In Australia, PrEP drugs were available, at "about $1,200 per month",[87] following the May 2016 approval of the Therapeutic Goods Administration.[88] Despite the lobbying to have these PrEP drugs subsidised under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme,[86][89] in August 2016 it was announced that the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee had rejected the proposal for this drug to be PBS-subsidised.[87][90] On 9 February 2018, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) announced that PrEP will be subsidised by the Australian Government through the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS).[91] The PBS subsidy came into effect on 1 April 2018, reducing the cost of PrEP to around $40 a month for eligible recipients.[92]

See also

- AIDS photo diary, 1986–1990

- Breastfeeding and HIV

- Health care in Australia

- HIV and men who have sex with men

- HIV and pregnancy

- HIV drug resistance

- HIV Drug Resistance Database

- HIV/AIDS research

- Management of HIV/AIDS

- Men who have sex with men

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- Post-exposure prophylaxis

- Subtypes of HIV

Bibliography

- Altman, Dennis (2001). Global Sex. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 216. ISBN 0-226-01606-4.

- Bowtell, William (May 2005). "Australia's Response to HIV/AIDS 1982–2005" (PDF; requires download). HIV/AIDS Project. Lowy Institute for International Policy.

References

- "HIV in Australia: Annual surveillance short report 2018" (PDF). Kirby Institute.

- Dalzell, Stephanie (10 July 2016). "AIDS epidemic no longer a public health issue in Australia, scientists say". ABC. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- "26 years of HIV/AIDS". World AIDS Day Australia. Archived from the original on 28 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 15.

- Ware, Cheryl. HIV survivors in Sydney : memories of the epidemic. Cham, Switzerland. ISBN 9783030051020. OCLC 1097183579.

- "Vision & History". Queensland Association for Healthy Communities. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "ACSA History". AIDS Council of South Australia. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "History". Western Australian AIDS Council. Archived from the original on 31 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Welcome to TasCAHRD". Tasmanian Council on AIDS, Hepatitis and Related Diseases. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "List of members". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "About the Trust". AIDS Trust of Australia. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Under The Red Ribbon". Victorian AIDS Council (VAC/GMHC). Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Message from the President". Bobby Goldsmith Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Who was Bobby Goldsmith?". Bobby Goldsmith Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Sendziuk, Paul. "Denying the Grim Reaper: Australian Responses to AIDS". Eureka Street. Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 18, 21.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 31.

- Plummer, D; Irwin, L (December 2006). "Grassroots activities, national initiatives and HIV prevention: clues to explain Australia's dramatic early success in controlling the HIV epidemic". International Journal of STD & AIDS. 17 (12): 787–793. doi:10.1258/095646206779307612. PMID 17212850.

- Kippax, Susan; Connell, R. W.; Dowsett, G. W.; Crawford, June (1993). Sustaining safe sex: gay communities respond to AIDS. London: Routledge Falmer (Taylor & Francis). p. 1.

- "Top ads? The creators have their say". The Age. 6 October 2002. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- Altman, D (1992). Timewell, E; Minichiello, V; Plummer, D (eds.). The most political of diseases. AIDS in Australia. Prentice Hall.

- "20 years after Grim Reaper ad, AIDS fight continues". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "HIV and AIDS discrimination and stigma". AVERT. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- "Grim Reaper's demonic impact on gay community". B&T. 1 October 2002. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 27.

- "Needle & Syringe Programs: a Review of the Evidence" (PDF). Australian National Council on AIDS, Hepatitis C and Related Diseases. 2000. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "Projecting Australia and its Values". Advancing the National Interest: Australia's Foreign and Trade Policy White Paper. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2003. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 10.

- "Our Projects: Hope For Children – Cambodia". The AIDS Trust. Archived from the original on 7 June 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Criminalisation of HIV transmission in Europe". The Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS Europe and The Terrence Higgins Trust. 2005. Archived from the original on 10 May 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Cameron, Sally (2007). "HIV on Trial". HIV Australia. 5 (4). Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- Roberts, Jeremy (1 February 2007). "HIV experts line up to refute denier". The Australian. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- "NHMRC says link between HIV and AIDS "overwhelming"" (Press release). National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). 4 May 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Corbett, Kate (7 February 2008). "An HIV-positive male prostitute has admitted to potentially spreading the deadly virus". News.com.au. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- "Man jailed for trying to spread HIV". Yahoo! News. 6 January 2009. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Bowtell 2005, p. 19.

- Sean Parnell (6 July 2012). "Sponsored workers bumping up HIV bill". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- "HIV foundation:Australian context". HIVfoundation.org.au. May 2018.

- Victorian Department of Human Services, Hospitals, AIDS & you Archived 2 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Dwan v. Farquhar, 1 Qd. R. 234, 1988

- "Health Ministers agree to new blood screening test" (Press release). Australian Health Ministers. 4 August 1999. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- Stott, Rob (19 May 2014). "Blood donation rules continue to exclude healthy donors". News Ltd. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Australian Red Cross Blood Service. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Fact Finder: Our response to news.com.au's gay blood donation article". Australian Red Cross Blood Service. 19 May 2014. Archived from the original on 8 June 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Koelmeyer, Rachel; McDonald, Karalyn; Grierson, Jeffery. "BEYOND THE DATA: HIV-POSITIVE WOMEN IN AUSTRALIA". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "HIV and women having children" (PDF). Better Health Channel. State of Victoria. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- World Health Organization (November 2013). "Preterm birth". who.int. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "HIV and AIDS in pregnancy". BabyCenter. BabyCenter Australia Medical Advisory Board. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) – perinatal". State Government Victoria. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "HIV STATISTICS IN AUSTRALIA: WOMEN". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- McDonald, Karalyn. "'You don't grow another head': The experience of stigma among HIV-positive women in Australia". HIV Australia. 9 (4): 14–17.

- "History". New Mardi Gras. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Altman 2001, p. 83.

- See for example the Publications List of participants in the National Centre in HIV Epidemiology & Clinical Research dating back to 1983.

- Lebihan, Rachel (16–17 April 2011). "Top class research fails to get local support". Weekend Australian Financial Review. p. 31.

- "National Centre in HIV Epidemiology & Clinical Research". Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- "Annual Report" (PDF). National Centre in HIV Epidemiology & Clinical Research. 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- "It's time to talk top: the risk of insertive, unprotected anal sex". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "Transmission, sexual acts". Bobby Goldsmith Foundation. 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- "Anal sex and risk reduction". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. 12 January 2011. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- "HIV and men – safe sex". Department of Health, Victoria. June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- Ezzy, D; De Visser, R; Grubb, I; McConachy, D (1998). "Employment, accommodation, finances and combination therapy: the social consequences of living with HIV/AIDS in Australia". AIDS Care. 10 (2): 189–199. doi:10.1080/09540129850124299. PMID 9743740.

- Ezzy, D; De Visser, R; Bartos, M (1999). "Poverty, disease progression and employment among people living with HIV/AIDS in Australia". AIDS Care. 11 (4): 405–414. doi:10.1080/09540129947785. PMID 10533533.

- Li, Yueming; McDonald, Ann M; Dore, Gregory J; Kaldor, John M (2000). "Improving survival following AIDS in Australia, 1991–1996". AIDS. 14 (15): 2349–2354. doi:10.1097/00002030-200010200-00016. PMID 11089623.

- "HIV Fact Sheet". Victorian Aids Council. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Lewis, Dyani (29 November 2013). "Living with HIV in 2013". ABC. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- McDonald, Ann (2006). "HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis & Sexually Transmissible Infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report" (PDF). National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- Altman 2001, p. 78.

- McDonald, Ann (2007). "HIV infection attributed to heterosexual contact in Australia, 1996 – 2005". HIV Australia. 5 (4). Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Govt considering funding AIDS campaign". The Sydney Morning Herald. AAP. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "The National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2005–2008: Revitalising Australia's Response". Department of Health and Ageing. Archived from the original on 22 July 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- Benson, Kate (19 October 2010). "HIV rate rising but other infections less common". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- Paynter, Heath. "HIV Statistics". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- "HIV in Australia" (PDF). Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Melissa Davey (23 July 2014). "Aids-free generation within reach if we boost HIV treatment, says Bill Clinton". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Michael Kirby (23 July 2014). "'The law can be an awful nuisance in the area of HIV/AIDS': Michael Kirby". The Conversation. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Decriminalisation of drug use – key to ending HIV". Health24. Health24. 22 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "To Protect and Serve". Open Society Foundations. Open Society Foundations. July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Australian Associated Press (19 July 2014). "MH17: AIDS conference organisers name six delegates killed in crash". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Haire, Bridget (14 September 2015). "Five reasons why HIV infections in Australia aren't falling". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Treating HIV". Queensland Positive People. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "HIV statistics in Australia: men". Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Akersten, Matt (14 September 2015). "New stats reveal how HIV treatments are changing sex lives". SameSame. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Melbourne posters saying gay men can "f*** raw" on PrEP follow report revealing record figures of condomless sex". 18 September 2015.

- Lewis, David. "PrEP: The blue pill being used to prevent HIV, Five perspectives on the drug awaiting approval in Australia". ABC News. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Spooner, Rania (19 August 2016). "HIV prevention drug Truvada won't be subsidised in Australia". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- Riley, Benjamin (3 March 2015). "Prep access for HIV prevention in Australia a step closer as Gilead applies to TGA". Star Observer. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Power, Shannon (19 August 2016). "Outrage as prep drug Truvada denied access to PBS". Star Observer. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)". Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "TENOFOVIR + EMTRICITABINE". Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). Retrieved 22 January 2019.

External links

Australian government official information source on HIV/AIDS:

The national peak organisations representing people living with or affected by HIV:

- National Association of People with HIV

- Australian Injecting & Illicit Drug Users League

- Scarlet Alliance, Australian Sex Workers Association

The National Federation of AIDS organisations:

The AIDS councils:

- AIDS Action Council of the ACT

- AIDS Council of New South Wales

- Northern Territory AIDS and Hepatitis Council

- Queensland Association for Healthy Communities

- AIDS Council of South Australia

- Tasmanian Council on AIDS, Hepatitis and Related Diseases

- Victorian AIDS Council

- Western Australian AIDS Council

Commonwealth government-funded research centres:

- The National Centre in HIV Social Research

- The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research (NCHECR)

Other HIV/AIDS organisations:

- Bobby Goldsmith Foundation

- AIDS Trust of Australia

- Positive Life NSW - the voice of people with HIV since 1988

- ASHM | Supporting the HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Workforce

HIV/AIDS initiatives in Australia:

- Melbourne Declaration | Action on HIV!

- Implementing the United Nations Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS in Australia's HIV Domestic Response: Turning Political Will into Action