Gyorche Petrov

Gyorche Petrov Nikolov born Georgi Petrov Nikolov (April 2, 1865 – June 28, 1921), was a Bulgarian revolutionary, one of the leaders of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees.[2] Despite his Bulgarian self-identification,[3][4] according to the post-World War II Macedonian historiography,[5][6] he was an ethnic Macedonian.[7][8]

Gyorche Petrov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 2, 1865 |

| Died | June 28, 1921 (aged 56) |

| Nationality | Ottoman/Bulgarian |

Biography

Born in Varoš (Prilep), Ottoman Empire (today North Macedonia), he studied at the Bulgarian Exarchate's school in Prilep and the Bulgarian Men's High School of Thessaloniki. Later he attended the Gymnazium in Plovdiv, capital of the recently created Eastern Rumelia. Here he joined the Bulgarian Secret Central Revolutionary Committee founded in 1885. The original purpose of the committee was to gain autonomy for the region of Macedonia (then called Western Rumelia), but it played an important role in the organization of the Unification of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. Afterwards, Petrov worked as a Bulgarian Exarchate's teacher in various towns of Macedonia. He took part in the revolutionary campaign in Macedonia as well as in the Thessaloniki Congress of the Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees (BMARC) in 1896.[9][10] He was among the authors of the organization's new charter and rules, which he co-wrote with Gotse Delchev.[11]

Gjorche Petrov was the representative of the Foreign Committee of the BMARC/IMARO in Sofia in 1897-1901. He did not approve of the ultimately outbreak of the Uprising on Ilinden, 2 August 1903, but he participated leading a squad.[12] After the unsuccessful uprising Petrov continued his participation in IMARO. The failure of the Uprising reignited the rivalries between the varying factions of the Macedonian revolutionary movement. The left-wing faction including Petrov, opposed Bulgarian nationalism but the Centralist's faction of the IMARO, drifted more and more towards it. Petrov was again included in the Emigrant representation in Sofia in 1905-1908. After the Young Turks Revolution of 1908, Petrov together with writer Anton Strashimirov edited the "Kulturno Edinstvo" magazine ("Cultural Unity"), published in Thessaloniki (Solun).[13] In 1911 a new Central Committee of IMARO was formed and the Centralists faction gained full control over the Organization.

During the Balkan wars, Gyorche Petrov was a volunteer in the 5th company of Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps.[14] He was President of the Regular Regional Committee in Bitola for some time during the First World War and Bulgarian administration in Vardar Macedonia and afterwards became mayor of Drama.[15] At the end of the war he was one of the initiators of the formation of a new leftist organization called Provisional representation of the former United Internal Revolutionary Organization, and this government set a task of defending the positions of the Bulgarians in Macedonia at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920).

He kept close ties with the new government of Bulgarian Agrarian National Union (BANU), especially with minister Aleksandar Dimitrov and some other prominent Agrarian leaders. BANU rejected territorial expansion and aimed at forming a Balkan federation of agrarian states, a policy which began with a détente with Yugoslavia. As result Petrov became a Chief of the Bulgarian Refugees Agency by the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Then Petrov had to deal with the problem of Bulgarian refugees who had to leave Yugoslavia and Greece, thus incurring IMRO Centralist faction leaders' hatred upon himself.[16] One of the reasons for this was the open struggle of the IMRO with the government of the BANU, and on the other hand, the interplay between the various refugees organizations and the attempt of IMRO to acquire them.

He was eventually killed by an IMRO-assassin in June 1921 in Sofia. The assassination of Gyorche Petrov complicated relations between IMRO and Bulgarian government and produced significant dissensions in the Macedonian movement.[17]

To honor his name a suburb of Skopje was named Gjorče Petrov, or usually shortly referred only as Gjorče. The suburb is one of the ten municipalities of Skopje, the capital of North Macedonia.

Gallery

Gyorche Petrov with his wife Jordanka

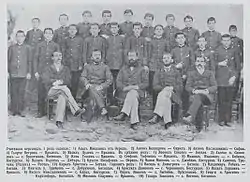

Gyorche Petrov with his wife Jordanka Gyorche Petrov with his squad

Gyorche Petrov with his squad Gyorche Petrov, Arseni Jovkov and Georgi Pop Hristov

Gyorche Petrov, Arseni Jovkov and Georgi Pop Hristov Monument of Gyorche Petrov in the park of the suburb named after him

Monument of Gyorche Petrov in the park of the suburb named after him Cover of his 1896 book of materials for study of Macedonia

Cover of his 1896 book of materials for study of Macedonia Diploma issued by the Bulgarian Gymnasium in Plovdiv, Eastern Rumelia to Petrov

Diploma issued by the Bulgarian Gymnasium in Plovdiv, Eastern Rumelia to Petrov

References

- As a result of the Salonica Congress in 1896 a new Statute and Rules, providing for a very centralized form of organization were drawn up by Gyorche Petrov and Gotse Delchev. The Statute and Rules were probably largely Gyorche's work, based on guidelines agreed by the Congress. He attempted to draw members of the Supreme Macedonian Committee into the task of drafting the Statute by approaching Andrey Lyapchev and Dimitar Rizov. When, however, Lyapchev produced a first article which would have made the Organization a branch of the Supreme Committee, Petrov gave up in despair and wrote the Statute himself, with Delchev's assistance.

- Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2009, ISBN 3-8258-1387-8, p. 135.

- Information from a book by Gyorche Petrov on the ethnic composition of the population in Macedonia: The Macedonian population consists of Bulgarians, Turks, Albanians, Wallachians, Jews The total number of the population and that of each nationality cannot be defined exactly as there are no statistics... Bulgarians constitute the bulk of the population in the vilayet I am describing. In spite of all distortions in the official statistics, they again figure as more than half of the population. I could not personally collect any data about the number of the population, that is why I am not quoting figures. I made a description of the Bulgarian population in the section on Topography, that is why it is not necessary to repeat the same again or go into detail... (G. Petrov, Materials on the Study of Macedonia), Sofia, 1896, pp. 724-725, 731; the original is in Bulgarian. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Institute of History, Bulgarian Language Institute, Macedonia. Documents and materials, Sofia 1978.Document # 40.

- In his memoirs, Gjorche Petrov calls himself Bulgarian: Gjorche Petrov's memoirs page 90: "Щомъ разбраха, че съмъ българинъ и пр." (After they found out I was a Bulgarian, etc.) Спомени на Гьорчо Петровъ, Съобщава Любомиръ Милетичъ (Издава "Македонскиятъ Наученъ Институтъ", София. — Печатница П. Глушковъ. — 1927) (Bg).

- According to Leslie Benson in Yugoslav Macedonia the past was systematically falsified to conceal the fact that many prominent 'Macedonians' had supposed themselves to be Bulgarian, and generations of students were taught that "pseudo-history" of the 'Macedonian nation. The mass media and education system were the keys to this process of national acculturation, speaking to people in a language that they came to regard as their 'Macedonian' mother tongue, even it was perfectly understood in Sofia. For more see: L. Benson, Yugoslavia: A Concise History, Edition 2, Springer, 2003, ISBN 1403997209, p. 89.

- The origins of the official Macedonian national narrative are to be sought in the establishment in 1944 of the Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. This open acknowledgment of the Macedonian national identity led to the creation of a revisionist historiography whose goal has been to affirm the existence of the Macedonian nation through the history. Macedonian historiography is revising a considerable part of ancient, medieval, and modern histories of the Balkans. Its goal is to claim for the Macedonian peoples a considerable part of what the Greeks consider Greek history and the Bulgarians Bulgarian history. The claim is that most of the Slavic population of Macedonia in the 19th and first half of the 20th century was ethnic Macedonian. For more see: Victor Roudometof, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, ISBN 0275976483, p. 58; Victor Roudometof, Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253-301.

- The first name of the IMRO was "Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Committees", which was later changed several times. Initially its membership was restricted only for Bulgarians. It was active not only in Macedonia but also in Thrace (the Vilayet of Adrianople). Since its early name emphasized the Bulgarian nature of the organization by linking the inhabitants of Thrace and Macedonia to Bulgaria, these facts are still difficult to be explained from the Macedonian historiography. They suggest that IMRO revolutionaries in the Ottoman period did not differentiate between ‘Macedonians’ and ‘Bulgarians’. Moreover, as their own writings attest, they often saw themselves and their compatriots as ‘Bulgarians’ and wrote in Bulgarian standard language. For more see: Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004) Historiography, Myths and the Nation in the Republic of Macedonia. In: Brunnbauer, Ulf, (ed.) (Re)Writing History. Historiography in Southeast Europe after Socialism. Studies on South East Europe, vol. 4. LIT, Münster, pp. 165-200 ISBN 382587365X.

- The modern Macedonian historiographic equation of IMRO demands for autonomy with a separate and distinct national identity does not necessarily jibe with the historical record. A rather obvious problem is the very title of the organization, which included Thrace in addition to Macedonia. Thrace whose population was never claimed by modern Macedonian nationalism...There is, moreover, the not less complicated issue of what autonomy meant to the people who espoused it in their writings. According to Hristo Tatarchev, their demand for autonomy was motivated not by an attachment to Macedonian national identity but out of concern that an explicit agenda of unification with Bulgaria would provoke other small Balkan nations and the Great Powers to action. Macedonian autonomy, in other words, can be seen as a tactical diversion, or as “Plan B” of Bulgarian unification. İpek Yosmaoğlu, Blood Ties: Religion, Violence and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908, Cornell University Press, 2013, ISBN 0801469791, pp. 15-16.

- Aleksieva, Margarita (1972). Some Great Bulgarians. Sofia Press. p. 157.

- Ashton, Oswald; Wentworth Dilke; Margaret S. Dilke (1984). Recollections of the National Liberation Struggles in Macedonia. Mosaic Publications. p. 13.

- Detrez, Raymond (1997). Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria. Scarecrow Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-8108-3177-5.

- Gjorche Petrov's memoirs page 167-8

- Генов, Георги. Беломорска Македония 1908 - 1916, Торонто, 2006, стр. 44.

- Александър Гребенаров. 86 години от смъртта на Гьорче Петров

- Николов, Борис Й. Вътрешна Македоно-Одринска революционна организация. Войводи и ръководители. биографично-библиографски справочник. София 2001, с. 128 (Nikolov, Boris. Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Organization. Voivodes and Leaders. Biographical and Bibliographical Reference Book. Sofia 2001, p. 128).

- Василев, Васил. Правителството на БЗНС, ВМРО и българо-югославските отношения, София 1991, с.77(Vasilev, Vasil. The Government of BANU, IMRO and the Bulgarian-Yugoslav relations, Sofia 1991, p. 77)

- Василев, Васил. Правителството на БЗНС, ВМРО и българо-югославските отношения, София 1991, с. 101-104. (Vasilev, Vasil. The Government of BANU, IMRO and the Bulgarian-Yugoslav relations, Sofia 1991, p. 101-104)