Gunnor

Gunnor or Gunnora (c. 950 – 5 January 1031) was the duchess of Normandy by marriage to Richard I of Normandy, having previously been his long-time mistress. She functioned as regent of Normandy during the absence of her spouse, as well as the adviser to him and later to his successor, their son Richard II.

| Gunnor | |

|---|---|

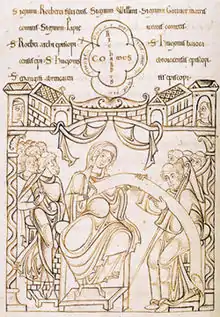

Gunnor confirming a charter of the abbey of the Mount-Saint-Michel, 12th century (from archive of the abbey). Here she attested using her title of countess.[1] | |

| Duchess consort of Normandy | |

| Tenure | 989–996 |

| Born | c. 950. Rouen, Haute-Normandy, France |

| Died | 5 January 1031 (not verified) Normandy, France |

| Spouse | Richard I, Duke of Normandy |

| Issue | Richard II Robert II, Archbishop of Rouen, Count of Evreux Mauger, Count of Corbeil Robert Danus Emma, Queen consort of England Hawise, Duchess consort of Brittany Maud, Countess of Blois |

Life

The names of Gunnor's parents are unknown, but Robert of Torigni wrote that her father was a forester from the Pays de Caux and according to Dudo of Saint-Quentin she was of noble Danish origin.[2] Gunnor was probably born c. 950.[3] Her family held sway in western Normandy and Gunnor herself was said to be very wealthy.[4] Her marriage to Richard I was of great political importance, both to her husband[lower-alpha 1] and her progeny.[5] Her brother, Herfast de Crepon, was progenitor of a great Norman family.[4] Her sisters and nieces[lower-alpha 2] married some of the most important nobles in Normandy.[6]

Robert of Torigni recounts a story of how Richard met Gunnor.[7] She was living with her sister Seinfreda, the wife of a local forester, when Richard, hunting nearby, heard of the beauty of the forester's wife. He is said to have ordered Seinfreda to come to his bed, but the lady substituted her unmarried sister, Gunnor. Richard, it is said, was pleased that by this subterfuge he had been saved from committing adultery and together they had three sons and three daughters.[lower-alpha 3][8] Unlike other territorial rulers, the Normans recognized marriage by cohabitation or more danico. But when Richard was prevented from nominating their son Robert to be Archbishop of Rouen, the two were married, "according to the Christian custom", making their children legitimate in the eyes of the church.[8]

Gunnor attested ducal charters up into the 1020s, was skilled in languages and was said to have had an excellent memory.[9] She was one of the most important sources of information on Norman history for Dudo of St. Quentin.[10] As Richard's widow she is mentioned accompanying her sons on numerous occasions.[9] That her husband depended on her is shown in the couple's charters where she is variously regent of Normandy, a mediator and judge, and in the typical role of a medieval aristocratic mother, an arbitrator between her husband and their oldest son Richard II.[9]

Gunnor was a founder and supporter of Coutances Cathedral and laid its first stone.[11] In one of her own charters after Richard's death she gave two alods to the abbey of Mont Saint-Michel, namely Britavilla and Domjean, given to her by her husband in dower, which she gave for the soul of her husband, and the weal of her own soul and that of her sons "count Richard, archbishop Robert, and others..."[12] She also attested a charter, c. 1024–26, to that same abbey by her son, Richard II, shown as Gonnor matris comitis (mother of the count).[13] Gunnor, both as wife and countess,[lower-alpha 4] was able to use her influence to see her kin favored, and several of the most prominent Anglo-Norman families on both sides of the English Channel are descended from her, her sisters and nieces.[9] Gunnor died c. 1031.[3]

Family

Richard and Gunnor were parents to several children:

- Richard II "the Good", Duke of Normandy[14]

- Robert, Archbishop of Rouen, Count of Evreux, died 1037[14]

- Mauger, Count of Corbeil[14]

- Robert Danus, died between 985 and 989[15]

- another son[15]

- Emma of Normandy (c. 985–1052), married first to Æthelred, King of England and secondly Cnut the Great, King of England.[14]

- Hawise of Normandy, wife of Geoffrey I, Duke of Brittany[14]

- Maud of Normandy, wife of Odo II of Blois, Count of Blois, Champagne and Chartres[14]

Notes

- Richard's marriage to Gunnor seems to have been a deliberate political move to consolidate his position by allying himself with a powerful rival family in the Cotentin. See: D. Crouch, The Normans (2007), pp. 26 & 42;A companion to the Anglo-Norman world, eds. C. Harper-Bill; E. van Houts (2007), p. 27.

- Her sisters, Senfrie, Aveline and Wevie as well as their daughters are discussed in detail in G.H. White, 'The Sisters and Nieces of Gunnor, Duchess of Normandy, The Genealogist, New Series, vol. 37 (1920-21), pp. 57–65 & 128–132. Also see: Elisabeth van Houts, 'Robert of Torigni as Genealogist', Studies in Medieval History Presented to R. Allen Brown, ed. Christopher Harper-Bill, Christopher J. Holdsworth, Janet L. Nelson (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1989), pp. 215–233; K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, 'Aspects of Torigny's Genealogy Revisited', Nottingham Medieval Studies, Vol. 37 (1993), pp. 21–28.

- Geoffrey H. White is among those historians who question the authenticity of this story. See: G.H. White, 'The Sisters and Nieces of Gunnor, Duchess of Normandy, The Genealogist, New Series, vol. 37 (1920-21), p. 58.

- At the time Gunnor lived, there were no dukes or duchesses of Normandy. Her husband Richard I, used the title of count of Rouen, to which Richard added the style of "count and consul", and after 960, marquis (count over other counts). Gunnor would have never used the title of duchess, her title was countess and she is so styled in an original deed to the abbey of St. Ouen, Rouen (1057–17) given by her son Richard II. For the present, despite being historically incorrect, duchess remains her title of convenience. See: Bates, Normandy before 1066 (Longman, 1982), pp. 148–50; Douglas, 'The Earliest Norman Counts', The English Historical Review, Vol. 61, No. 240 (May, 1946), pp. 130–31; David Crouch, The Normans: The History of a Dynasty (London: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), pp. 18–19 and Dudo of Saint-Quentin; Eric Christiansen, History of the Normans (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1998). p. xxiv.

References

- David Crouch, The Image of Aristocracy in Britain, 1000-1300 (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 57

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 58

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 40 n.56

- David Crouch, The Normans; the History of a Dynasty (London, New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), p. 26

- K.S.B. Keats-Rohan, 'Poppa of Bayeux and Her Family', The American Genealogist, Poppa of Bayeux and Her Family, Vol. 74, No. 2 (July/October 1997), pp. 203–04

- David Crouch, The Normans; the History of a Dynasty (London, New York: Hambledon Continuum, 2007), pp. 26–27

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 95

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 96

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 59

- Elisabeth M. C. Van Houts, Memory and Gender in Medieval Europe: 900–1200 (Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1999), p. 72

- Elisabeth Van Houts, The Normans in Europe (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008), p. 40 & n. 56

- Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, ed. J. Horace Round (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1899), p. 250

- Calendar of Documents Preserved in France, ed. J. Horace Round (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1899), p. 249

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band II (Marburg, Germany: J. A. Stargardt, 1984), Tafel 79

- Elisabeth van Houts, The Normans in Europe, p. 191

| Preceded by Emma of Paris |

Duchess of Normandy 989–996 |

Succeeded by Judith of Brittany |