Guerrilla warfare in the Peninsular War

Guerrilla warfare in the Peninsular War refers to the armed actions carried out by non-regular troops against Napoleon's Grand Armée in Spain and Portugal during the Peninsular War. These armed men were a constant source of harassment to the French army, as described by a Prussian officer fighting for the French: "Wherever we arrived, they disappeared, whenever we left, they arrived — they were everywhere and nowhere, they had no tangible center which could be attacked."[1] The Peninsular War was significant in that it was the first to see a large-scale use of guerrilla warfare in European history and as a result of the guerrillas, Napoleon's troops were tied down on the Iberian peninsula, unable to conduct military operations elsewhere on the continent.[2] The strain the guerrillas caused on the French troops led Napoleon to dub the conflict the "Spanish Ulcer."[3]

.png.webp)

Course of the war

Apart from the odd setback, such as General Castaños' surprise victory at Bailén, in part due to guerrilla warfare between Madrid and Andalusia, and especially in the Sierra Morena, a victory which helped persuade the British government that Napoleon could be defeated, the French troops were largely undefeated on the open battlefield.

A list drawn up in 1812 puts the figure of such irregular troops in Spain alone at 38,520 men, divided into 22 guerrilla bands.[4]

Although locally organised militia had been deployed in Portugal and Spain before, particularly in the regions of Catalonia and Valencia, where thousands of well-organised "miquelets" (in conjunction with local militias known as "somatenes") had already proved their worth in the Catalan revolt of 1640 and in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714),[5] it was during the Peninsular War, referred to by Spaniards as the War of Independence, that such armed forces became active on a nationwide basis.

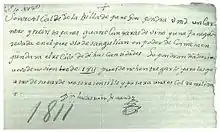

Well aware of how successful both urban and rural guerrilla warfare had been so far, on 28 December 1808 the Junta Central Suprema issued the Reglamento de partidas y Cuadrillas, a decree regulating the formation of guerrilla troops.[6] This would be followed by other decrees in 1809, authorising the "Corso Terrestre" ("Land Corsairs") to keep for themselves any money, supplies and equipment that they were able to take from the French.[4] In effect, in some cases, this meant that they were little more than brigands who were, in some cases, feared by French troops and the civilian population alike.[7] Little by little, these groups would be incorporated into the regular Spanish Army and their cabecillas (leaders) given regular military ranks.

Spanish guerrillas frequently attacked Grand Armee rear echelon components, including communication and supply lines. These guerrillas were mainly ordinary civilians, predominantly from rural areas and generally conscripted. The success of these fighters in the conflict was owed to the few men and small amount of equipment and energy required to hold a large area and disrupt French movements. Despite a French victory in the conventional war, the unconventional war simply could not be won.[8] The stress of the guerrilla conflict put considerable strain on Napoleon who remarked that the affair had been the one "that killed me."[9]

By the end of 1809, the damage caused by the guerrillas led to the Dutch Brigade, under Major-General Chassé, being deployed, almost exclusively and, largely unsuccessfully, in counter-guerrilla warfare in La Mancha.

Notable actions

- Battle of Arlabán (1811) – a Spanish guerrilla force numbering between 3,000 and 4,500 men, led by Francisco Espoz y Mina, ambushed and captured the central part of a convoy made up of 150 wagons and 1,050 prisoners, escorted by 1,600 French troops led by Colonel Laffitte and spread out over five km at a mountain pass along the road to France. The convoy was valued at four million reales, and 1,042 British, Portuguese and Spanish prisoners were liberated in the raid.

- Battle of Puente Sanpayo (1809) the army of French marshal Michel Ney is defeated by the Spanish army. As Ney's troops retreat they come under harassing fire from guerrilla forces, inflicting even more casualties.

Famous guerrilleros

Folklore would often elevate the status of local heroes, but some of the better-known guerrilleros include the following:

- Francisco Abad Moreno "Chaleco"

- Agustina de Aragón

- Francisco Espoz y Mina

- Joaquín Ibáñez, Baron de Eroles

- Francisco de Longa

- Juan Martín Díez "El Empecinado"

- Julián Sánchez García (1771-1832), known as "el Charro"

- Jerónimo Merino (1769–1844), known as "el Cura Merino"

- Martin Xavier Mina[10]

- Tomás de Zumalacárregui (briefly)

References

- Talbott, John (1978) "Guerrilla Warfare" Virginia Quarterly Review. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Rupert Smith (16 January 2007). The Utility of Force. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 153–. ISBN 978-0-307-26741-2.

- David Nicholls (1999). Napoleon: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-0-87436-957-1.

- Esdaile, Charles J. (2004) Fighting Napoleon: Guerrillas, Bandits and Adventurers in Spain, 1808-1814, pp. 106–8. Yale University Press At Google Books. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 566.

- (in Spanish) "Guerrilleros" El Periódico de Aragón. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Cathal Nolan (2 January 2017). The Allure of Battle: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost. Oxford University Press. pp. 229–. ISBN 978-0-19-991099-1.

- René Chartrand (20 March 2013). Spanish Guerrillas in the Peninsular War 1808–14. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-0316-0.

- David Nicholls (1999). Napoleon: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. pp. 197–. ISBN 978-0-87436-957-1.

- (in Spanish) "El jefe del Corso Terrestre y un héroe de México" Diario de Navarra. Retrieved 14 September 2013.