Grand River Railway

The Grand River Railway (reporting mark GRNR) was an interurban electric railway in what is now the Regional Municipality of Waterloo, in Southwestern Ontario.

.jpg.webp) Grand River Railway Steeple Cab 230 seen in September 1963, after the end of passenger service and dieselization of the line. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Preston, Ontario |

| Reporting mark | GRNR |

| Locale | Waterloo County, Ontario, Canada |

| Dates of operation | 1914–1931 |

| Predecessor | Berlin, Waterloo, Wellesley, and Lake Huron Railway |

| Successor | Canadian Pacific Electric Lines CP Waterloo Subdivision |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Overhead, originally 600 V DC, 1500 V DC after 1921 |

| Length | 30 km (19 mi)[1] |

Galt to Waterloo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Preston to Hespeler | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Preston and Berlin Railway

Starting in the 1850s, Canada West (today's province of Ontario) began to see its first railways. Of these, the first chartered was the Great Western Railway, which was completed in 1853-54 and connected Niagara Falls to Windsor via London and Hamilton, linking many contemporary centres of population, industry, and trade. in 1855, a branch line was built to Toronto, which fell on the east side of the Grand River, connecting towns and villages in the area such as Galt, Hespeler, Preston, and Guelph. Galt and Guelph in particular were developing into significant urban areas in the region.

In the following year of 1856, the Grand Trunk Railway, the dominant railway in Canada East (today's province of Québec), made a major westward push by acquiring the fledgling Toronto and Guelph Railroad, whose line was then under construction, and extended this line to Sarnia through Berlin (today's Kitchener). Once complete, this made Guelph a major three-way rail junction. In this climate of rapid rail development, ambitious town boosters sought to have their town or village also become a railway junction in the hopes that it would transform it into a city overnight. The merchants of Preston, who saw themselves as being in direct competition with those of Galt, quickly worked to establish a railway which would connect the Great Western and Grand Trunk through their own town and the town of Berlin across the river. In 1857, their dream would be realized with the completion of the Preston and Berlin Railway, which was routed through the small mill towns of Doon and German Mills, with a bridge crossing the Grand River north of Blair. This initial attempt to connect the two cities was short-lived, however, as the bridge was damaged by ice flows in January 1858, and the railway was operational for less than three months. The surviving sections of the line were sold to the Grand Trunk Railway, which instead chose to extend the line south to Galt through the village of Blair in 1872, bypassing Preston entirely.[2]

Early street railways

The Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway began operation in 1888 as a firmly 19th-century-style horse-drawn street railway. However, things would quickly change; by the 1890s, the tone of railway fever had shifted, and many radial railways were being developed throughout Canada and the United States, as cities like Toronto and New York accelerated the process of amalgamation of nearby villages and towns, and urban businesses sought out customers travelling to the city from the suburbs. These systems were typically electrified rather than steam-powered, and used tram-style rolling stock to move a relatively small number of passengers at frequent headways within a region, rather than more traditional passenger trains pulled by dedicated locomotives, which were largely relegated to long-haul trips. Growing towns and cities sought the ideal hybrid system of streetcars and railways: a light rail service which could easily shift from street rails to freight corridors and back again, allowing it to connect to important destinations in downtown areas while also being fast enough to connect cities to each other at the speed expected of contemporary passenger rail. These systems were often also known as interurbans due to the appeal of easily connecting neighbouring cities together with a regional rail line, often municipally owned and operated.

The first such railway in the region was the Galt and Preston Street Railway (G&P), which began operations with half-hourly service in 1894.[3]:9 With Preston boosters still concerned about the potential effect of the railway on their town's economy, the plan ensured that Preston would be the location of many operational aspects of the railway, including the power house, car barns, and machine shops. A year later, in 1895, it was extended to Hespeler and renamed the Galt, Preston and Hespeler Street Railway (GP&H),[4] connecting the three largest settlements of what 80 years later would become the amalgamated city of Cambridge. In the same year, the Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway began to take steps to modernize its service by converting its horse cars to run on electric power. This proved unsuitable and a consortium of local businessmen, impatient at the lack of progress, purchased the railway and outfitted it with new, purpose-built electric trams, which were manufactured in Peterborough.

Canadian Pacific Railway influence

Canadian Pacific had from the beginning taken an interest in the G&P, then the GP&H, as an electric freight service would provide a convenient way to serve smaller freight customers profitably, due to the ability for electric locomotives to reverse without requiring a loop, as steam locomotives did. The G&P's charter, ostensibly mostly to provide Preston travellers with a connection to the Canadian Pacific via Galt, as well as to facilitate regional passenger transportation in general, provided Canadian Pacific an opportunity to "piggyback" and increase its freight operations. The Grand River area had long been dominated by the Grand Trunk Railway, and CP sought ways to compete with the Grand Trunk. With its close relationship with Canadian Pacific, the G&P provided free freight service to Canadian Pacific's depot in Galt, drawing business away from the Grand Trunk and provoking an all-out freight war. In the truce agreed upon by both companies, Berlin remained Grand Trunk territory, while both railways would continue to serve Galt.[3]:14 Canadian Pacific, meanwhile, took control of the GP&H indirectly by buying up a controlling stake in the company through a proxy, its own General Superintendent J. W. Leonard, already laying the groundwork for the undermining of its agreement with the Grand Trunk.[3]:15

By the turn of the century, there was an explosion in plans for railway lines to serve Berlin, Preston, and Galt; the Hamilton Radial Electric Railway announced a plan to build a connection to Berlin, while the plan for a Preston-to-Berlin connection via Doon and Blair was revived. In 1903, the Preston & Berlin Street Railway, which had been chartered in 1894 and whose construction had begun in 1900, was leased by the GP&H, and began operations in 1904.[5] A Berlin, Waterloo, Wellesley, and Lake Huron Railway was being promoted at the same time, which was planned to have served a staggering number of destinations from Berlin northward to Lake Huron. However, with many of its promoters and supporters being connected to Canadian Pacific and the GP&H, and without the funds for such an ambitious project, it has been argued that the BWW&LH was never planned to be constructed, and was simply a vehicle to further Canadian Pacific's ambitions to enter into Kitchener, despite its agreement with the Grand Trunk a decade earlier.[3]:26 In 1908, the GP&H and Preston and Berlin Street Railway were merged under the BWW&LH name, thereby giving Canadian Pacific a means to enter the Kitchener freight market, while ostensibly following the letter of its agreement with the Grand Trunk. In 1914, it was renamed to the Grand River Railway.

As CP's consolidation of lines with freight potential had been ongoing, the City of Berlin made a successful bid to take over the Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway and operate it as a public service, which was complete in 1906. This line, which operated primarily along King Street, largely served commercial areas, and was most suitable for passengers, but served a role similar to local bus services today, rather than a regional railway role similar to the GRNR. In 1921, this separation of services increased as the GRNR re-routed its trains to more fully follow the north–south freight line as a part of its switch from 600 VDC to 1500 VDC electrification in order to match the Lake Erie and Northern Railway, a move which prefigured their consolidation ten years later.[6] Throughout the rest of the 1920s, the GRNR continued to shift to using shared freight track, a move which was hastened by municipal politicians working to force trains off of King Street in favour of car traffic.[3]:40

CP Electric Lines

In 1931, the Lake Erie and Northern Railway (LE&N), another CP Rail subsidiary, was consolidated with the GRNR to form the Canadian Pacific Electric Lines (CPEL). Under unified CPEL management, the two services were advertised in tandem, and LE&N rolling stock would receive repairs at the GRNR's Preston barn. During the same year, the GRNR advertised hourly service on every day except Sunday between Galt, Hespeler, Preston, and Kitchener, from 5:50 a.m. to 11:45 p.m., and nine trains a day (except on Sundays) to Waterloo, reflecting Waterloo's lesser importance and smaller population at the time.[7] The longer-distance and less-trafficked LE&N advertised primarily for summer excursion trips to Port Dover from the hot and crowded urban centres to the north.

Bus services became increasingly common throughout the 1920s and 1930s as more roadways were paved, fuel prices dropped, and bus manufacturing began to scale up. Canadian Pacific followed these trends with the founding of its Canadian Pacific Transport Company, which was used to supplement and/or replace some train journeys. In 1938, the first stage of the Grand River Railway's abandonment of passenger services occurred, when service between Kitchener's Queen Street and Waterloo's Allen Street was discontinued and replaced by bus service, necessitating a linear transfer for passengers.[3]:28 Ironically, passenger ridership had yet to hit its peak, which would be nearly 1.7 million riders in 1940.[3]:46

Despite the overall success of the combined CPEL railway system, post-Second World War social trends began to cause a drop in ridership as regional travellers became increasingly likely to own and drive cars. The beginning of residential subdivision development stimulated population growth outside of the historic downtowns of Berlin (by then renamed to Kitchener), Galt, and Preston, and they began to fall victim to urban decay. In the years following the 1919 Canada Highways Act, which provided stimulus funding for highway development, it became more practical and desirable to travel intercity by car, and development and urban planning began to adjust to car-centric transportation with road widening, highway development, creation of low-density residential housing subdivisions, and demolition of many urban buildings to provide parking, creating an induced demand feedback loop that favoured further car-centric development, while many railway systems were discontinued or statically maintained, without significant expansion of track, upgrades to rolling stock, or sometimes even basic maintenance; the Kitchener & Waterloo Street Railway, which had been put under the management of the Kitchener Public Utilities Commission, was rendered disabled even before its planned shutdown due to damage to the overhead electrical wires which was not repaired.

In 1946, Grand River Railway passenger service declined again, as the CP Transport Company's bus service was extended through Kitchener, and train and bus service alternated hourly. This followed a general trend, as train service was replaced with bus service on many railways, creating a downward spiral as ridership declined and train journeys with low ridership were cut or replaced with bus service.[3]:51 It was around this time that Canadian Pacific began to plan for total abandonment of passenger services along the line, even as freight carloads and profitability increased. In its first bid to discontinue service in 1950, CP's application was denied by Canada's Board of Transport Commissioners, but an allowance was made for CP to modify service as necessary to maintain profitability of passenger trips; as a direct result, CP discontinued nighttime passenger service altogether, and increased fares, making train journeys even less attractive to passengers.[3]:29 Nevertheless, rail service continued until April 23, 1955, when it was replaced by bus service under the Canadian Pacific Transport Company. Bus service operations for Preston were sold to Canada Coach Lines Limited later that year, but Galt-to-Kitchener operations continued under the Canadian Pacific umbrella until October 1, 1961, when freight service was dieselized and assumed by the parent CPR.

Around the time of the shift to diesel and abandonment of passenger service, the most extensive modification ever made of the railway's right of way was approved. It was internally referred to as Plan No. 1251, which called for the southwest Kitchener portion of the line to be relocated from King Street to the newly built Industrial Park (today's Parkway and Trillium Industrial Park areas), cementing the shift from passengers to freight. The previous right-of-way along King had served early 20th century suburban residential areas like Kingsdale, and villages-turned-suburbs like Centreville; in contrast, the rail line's new location primarily served a new industrial park built in farm fields, which would only later be joined by the residential and commercial area that grew up around Fairview Park Mall, which was built in 1965 as one of Kitchener's first suburban shopping malls. This shift allowed for the construction of Highway 8 as a separate-but-overlapping roadway (rather than simply a designation for King Street), obliterating much of the area's former rail infrastructure from Kitchener to Preston, and cementing the shift to an autocentric built environment. The seeds had been sown decades before, as municipal officials, who controlled the municipal right-of-way used for railway street running, began in the 1920s to deny the Grand River Railway's applications for renewal of their rail line's leases, forcing the railway into costly track relocations, which gradually forced the rail line further to the west of Kitchener's downtown, making it less convenient for passengers, and creating more room for the auto traffic which would prove to further interfere with railway operations.[3]:40

Rolling stock

Most of the Grand River Railway's rolling stock was built and maintained locally by the Preston Car Company,[8] which also manufactured cars for interurban railways throughout North America. The Preston plant closed in 1922,[9] however, and the railway turned to other manufacturers. In 1947, it commissioned Grand River Railway Car No. 626, a combination passenger and baggage motor car which seated eighteen passengers and was powered by four 125-hp Westinghouse motors, from National Steel Car of Hamilton, Ontario.[10] This was the last interurban railway car ever manufactured in Canada.[9] In its short service life, it became the regular car on the run between Kitchener-Waterloo and the Galt intercity CPR station.[10] It was used for at least one of the excursion trips by railway enthusiasts which occurred after the end of regular revenue service,[10] and was planned to be converted into a maintenance of way car or to be sold. With neither of these possibilities materializing, it was scrapped at Preston on 21 May 1957.[10]

Infrastructure

Trackage

Throughout its existence, the Grand River Railway's infrastructure changed to reflect the priorities and prosperity of its owners. Its complex track network included multiple former railways it had been consolidated into (primarily the GP&H) as well as related, but separate, railways such as the Kitchener and Waterloo Street Railway. As the system aged, its physical infrastructure came to reflect an increasing emphasis on freight. Lighter rail which was more suitable for single passenger cars than freight trains was gradually replaced. For example, the lighter 56-lb. rail on the Hespeler branch was replaced with 65-lb. rail in the early 1910s,[11]:10 and most of the mainline between Preston and Kitchener was relaid with 85-lb. rail in 1918.[11]:15

Stations

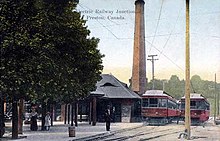

Emerging as it did from late 19th century street railways, the Grand River Railway system relied on simple trackside passenger shelters and short industrial spurs for freight servicing, while also utilizing several purpose-built stations. One of the most significant stations was Preston Junction, which sat near the centre of the line and was located at the junction leading to the Hespeler branch. As street running portions of track were gradually relocated, the emphasis on stations increased. With interurban trains banished from King Street in Kitchener after 1919, a basic wooden station was built in 1921 near the railway crossing at Queen Street,[11]:15 just outside of downtown to the southwest of Schneider Haus. While a distance away from Kitchener's main corridor of King Street, it was located in a then-rapidly growing suburban neighbourhood dominated by St. Mary's General Hospital, which opened in 1924. This created a direct connection between the St. Mary's area and the Freeport Sanitorium, which opened in 1916.[12] This Queen Street station was replaced by a "new and attractive"[11]:21 brick station in November 1943, corresponding to a heavy increase in passenger traffic during the Second World War,[11]:21 and coming several years after the discontinuance of service to Waterloo, which turned Kitchener Queen Street into a terminal station.[11]:20

Legacy

Much of the Grand River Railway's track continued to function as freight track for decades after it was shut down, but significant sections were removed in the 1980s, including the Hespeler branch, of which some portions are now the Mill Run Trail. Urban sections in Kitchener-Waterloo were largely also dismantled in the 1980s and replaced by the Iron Horse Trail in 1997, which features a number of plaques commemorating Kitchener's railway and industrial heritage. Perhaps most decisively, the junction that joined the GRNR and LE&N at Main Street in downtown Galt was also removed along with the LE&N track leading south to Paris, severing the original branch line laid down by the Great Western Railway in 1855, and ending rail traffic between the north and south halves of the Grand River valley.

A remnant of the GRNR/CPEL line, designated as the CP Waterloo Subdivision, remains an active rail corridor. From the Canadian Pacific mainline in the south (in the form of the Galt Subdivision), the line passes north through Galt and Preston, crossing the Speed River along approximately the same route as the Grand River Railway. North of the river, there is an industrial spur to reach a Toyota automobile factory. The line continues along its historic path, crossing the Grand River. It eventually deviates from the historic route, curving to the west and following the 1963 Grand River Railway rerouting through the Parkway industrial area. After curving to the north again, it joins with the CN Huron Park Spur at an interchange yard.

The Grand River is also referenced in the name of Grand River Transit, which was formed in 2000 through a merger of Kitchener Transit and Cambridge Transit. It provides regional transit connections between many areas once served by the Grand River Railway.

Starting in the 1990s, planners and local government officials began to revisit the idea of a rapid transit system in the region. This culminated in the Ion rapid transit light rail system which opened to the public on 21 June 2019.[13] Ironically, this system (ION Stage 1) does not include either Galt or Preston, the original hubs for regional rail, and is instead centred on Kitchener-Waterloo. It does, however, include portions of the Grand River Railway line. Ion's Stage 2, which as of 2019 is still in the public consultation phase, would once again provide a passenger rail connection between Galt, Preston, and Berlin (Kitchener).[14][15]

See also

References

- "Grand River Valley". Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- http://www.walterbeantrail.ca/prestonberlin.htm

- Cain, Peter F. (6 May 1972). The Grand River Railway: A Study of a Canadian Intercity Electric Railroad (Thesis). Department of History, Waterloo Lutheran University.

- Bean, Bill (24 October 2014). "LRT began in Galt and Preston in 1894". Waterloo Region Record. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "PRESTON & BERLIN STREET RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED PRESTON & BERLIN RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED". Trainweb. Trainweb. 19 July 2004. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- "CAMBRIDGE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON WATERLOO REGION'S LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Canadian Interurban Electric Railroads - 1930's - 1940's Grand River Railway Lake Erie & Northern Railway". 14 June 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "Grand River Railway". Canada-Rail.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Merrilees, Andrew (1963). "THE RAILWAY ROLLING STOCK INDUSTRY IN CANADA: A History of 110 Years of Canadian Railway Car Building". Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- "A TRIBUTE TO THE LAST ELECTRIC INTERURBAN CAR BUILT IN CANADA: GRAND RIVER RAILWAY 626". Trainweb.org. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Mills, John M. (1977). "Chapter I: Galt, Preston & Hespeler Street Railway, Grand River Railway". Traction on The Grand: The Story of Electric Railways along Ontario's Grand River Valley. Railfare Enterprises. ISBN 0-919130-27-5.

- Flanagan, Ryan (22 June 2016). "Grand River Hospital's Freeport campus marks 100-year milestone". CTV News. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Weidner, Johanna (2019-05-08). "Ion launch date set for June 21". TheRecord.com. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Sharkey, Jackie (8 February 2017). "There's still wiggle room in the Region of Waterloo's LRT plans for Cambridge". CBC. CBC. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Sharkey, Jackie (February 2017). "Stage 2 ION: Light Rail Transit (LRT)" (PDF). Region of Waterloo. Region of Waterloo. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

Further reading

- Cain, Peter F. (6 May 1972). The Grand River Railway: A Study of a Canadian Intercity Electric Railroad (Thesis). Department of History, Waterloo Lutheran University.

- Mills, John M. (1977). "Chapter I: Galt, Preston & Hespeler Street Railway, Grand River Railway". Traction on The Grand: The Story of Electric Railways along Ontario's Grand River Valley. Railfare Enterprises. ISBN 0-919130-27-5.

- Roth, George; Clack, William (April 1987). Canadian Pacific's Electric Lines: Grand River Railway and the Lake Erie & Northern Railway. British Railway Modellers of North America. ISBN 0919487211.

- Sandusky, Robert J. (July–August 2010). "Canadian Pacific Electric Lines – History Overview" (PDF). Canadian Rail. Canadian Railroad Historical Association (537). ISSN 0008-4875.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand River Railway. |