Giulio Campagnola

Giulio Campagnola (Italian: [ˈdʒuːljo kampaɲˈɲɔːla]; c. 1482 – c. 1515) was an Italian engraver and painter, whose few, rare,[1] prints translated the rich Venetian Renaissance style of oil paintings of Giorgione and the early Titian into the medium of engraving; to further his exercises in gradations of tone, he also invented the stipple technique, where multitudes of tiny dots or dashes allow smooth graduations of tone in the essentially linear technique of engraving; variations on this discovery were to be of huge importance in future printmaking. He was the adoptive father of the artist Domenico Campagnola.

Life

His early years are better documented than his adult life. He was born in Padua, then subject to the republic of Venice, and home to one of the three major European universities of the fifteenth century, the University of Padua. His father Girolamo was characterised by A. Hyatt Mayor as "a writer of some note, probably also an amateur artist, who belonged to what would now be called the intelligentsia";[2] letters by him in very good humanist Latin survive. According to Giorgio Vasari, Girolamo was also an artist "a Paduan painter and disciple of Squarcione",[3] but this remark is the only evidence for that.

A number of sources, including Vasari, say that Campagnola was extremely accomplished in a number of artistic areas as a teenager. A letter written by a relative when he was fifteen describes him as a talented poet, singer and lutenist, able to read Latin, Greek and Hebrew, and skilled in painting, engraving and cutting gemstones. This letter was sent to the court at Mantua (where Andrea Mantegna was then the court artist) in an attempt to find him a position there. It is not clear if he ever went to Mantua, although (like nearly all contemporary Italian printmakers) his work shows the influence of Mantegna. One engraving is certainly based (perhaps not directly, as there was another print of it) on a drawing by Mantegna or his workshop.[4]

In 1499 he appears (rather briefly) in the accounts of the court at Ferrara, another centre of North Italian printmaking. There is then no documentation until 1507, when another Paduan recorded lending him a painting and three copper engraving plates. This was in Venice, where most writers assume he was living by then. His engraving of an Astrologer is dated 1509 on the plate, and the only later record comes from the will of Aldus Manutius in 1515, when Manutius asks that he be given the work of cutting the moulds for, or perhaps designing, some printing type. At the period he also became a friend of the humanist and alchemical poet Giovanni Aurelio Augurello. Depicting his experiments with artificial blue pigments in his Chrysopoeia (Venice 1515) Augurello refers to Giulio ("meus Iulius") as the one person who at least is somehow profiting from the vain quest for gold.[5]

After this there is no further record, but an engraving plate that he had left half-finished was completed by his adopted son c. 1517, so he is assumed to have died by then at the latest, probably in Venice. He had adopted Domenico Campagnola, apparently an orphan of German parentage, in about 1512. Another source claimed that he took holy orders, but this is now discounted.

Fortunately, for those seeking to reconstruct his career, he was in the habit of signing, though not dating, his engravings, often with his full name and Antenoreus, a slightly showy learned reference to the Trojan whom Virgil designated the founder of Padua.

Professional status

Most writers see Campagnola as a professional artist, who received some sort of training in Mantua, Ferrara or Venice. Vasari describes him as a painter, and the Venetian connoisseur Marcantonio Michiel mentions cabinet paintings that were ascribed to him in Venetian collections in about 1530, but no paintings are generally attributed to him, although he is often brought into arguments about the many "Giorgionesque" paintings without an agreed attribution. He is often given a share in the fresco cycle in the Scuola del Santo at Padua, attributed to his son Domenico.

There are drawings related to his prints, and in a similar style to them, but only a handful of these are generally agreed to be by him, with Titian, Giorgione and in one case Mantegna also being brought into contention.[6][7] It is still possible to see Campagnola, as W.R. Rearick did, as a "dilettante" who probably mostly lived in Padua, probably with another career altogether. This, however, remains a minority view.

Most of his prints have no surviving preparatory drawings, and in general the question of whether Campagnola designed them himself or engraved then after drawings provided by other artists remains open. Most historians, however, see him as an independent artist responsible for conceiving as well as executing most of his prints, rather than a precursor of Marcantonio Raimondi or Domenico Campagnola who acted as a technical collaborator with a greater artist who supplied the designs.

Work

The dating of his work is based very largely on the stylistic arrangement of his work around the Astrologer, dated 1509, and his presumed death around 1515. Whilst the chronological sequence of his engravings set out by Arthur M. Hind has been generally accepted, the dating of them remains a subject for discussion. His early work is heavily influenced by Albrecht Dürer, and includes one direct copy of a Dürer engraving, and a few where landscape elements are copied from Dürer.[8][9] He also included a portrait of Dürer in his Marriage of the Virgin Mary, which Dürer himself may have drawn.[10]

The next group of engravings, which include the Astrologer, very successfully interpret the mood of Venetian painting of the first decade of the century in the medium of engraving. It is this group that he is most famous for, and that also introduce his stipple technique. Stippling means engraving with dots or little flicks of the burin, rather than the normal lines. Campagnola is able to convey varying tone by different intensities of dots, rather than by techniques of hatching and cross-hatching usually necessary.[11]

These engravings are in a combination of line and stipple work, and in the case of three of them (see gallery: The Old Shepherd,[9] The Young Shepherd and The Astrologer),[9] there are first states which are purely in line-work. The plates were later reworked in stipple work, in at least one case after a considerable number of impressions of the first state had been taken. The final group of prints are almost entirely in stipple, except for the main outlines.[9] There are also some prints in Campagnola's manner of which the authorship is disputed.

Two Naked Women, an early print, 11.9 × 18.1 cm

Two Naked Women, an early print, 11.9 × 18.1 cm Leda and the Swan, a disputed attribution

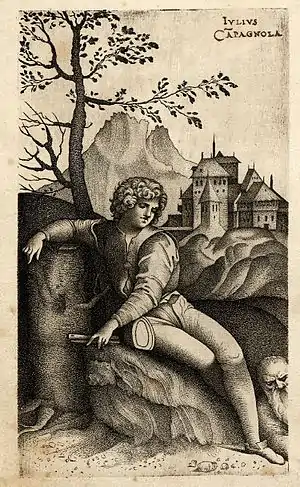

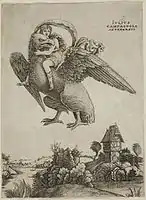

Leda and the Swan, a disputed attribution Ganymede carried off

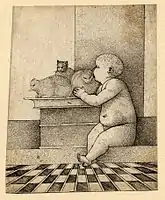

Ganymede carried off Baby with Three Cats, perhaps an exercise in stipple technique

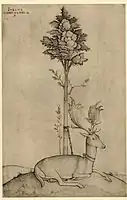

Baby with Three Cats, perhaps an exercise in stipple technique Stag tethered to a tree

Stag tethered to a tree "Venus", or reclining nude

"Venus", or reclining nude The Old Shepherd

The Old Shepherd

See also

References

- His total oeuvre consists of about fifteen engravings (Mark Zucker, The Illustrated Bartsch, Commentary 35; Patricia Emison, "Asleep in the Grass of Arcady: Giulio Campagnola's Dreamer" Renaissance Quarterly 45.2 (Summer 1992:271-292) p. 274 note 4; the Metropolitan Museum of Art had only seven prints by him when A. Hyatt Mayor described the three most recent acquisitions (Mayor, "Giulio Campagnola" The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 32.8 (August 1937:192-196).

- Mayor 1937:194

- Vasari, Giorgio (1851). Lives of the most eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. 2. London: H.G. Bohn.

- Campagnola: Saint John the Baptist, National Gallery of Art.

- The relationship is depicted in Dal Canton, Giuseppina: Giulio Campagnola 'pittore alchimista’ (I), Antichità viva 16/5 (1977), pp. 11-19; part (II) ibid 17/2 (1978), pp. 3-10.

- Giulio Campagnola or Possibly Giorgione: Jupiter and Ganymede above an Extensive Landscape, National Gallery of Art.

- Giulio Campagnola: Landscape with Two Men Sitting near a Coppice Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Louvre.

- Giulio Campagnola: the Rape of Ganymede, Metropolitan Museum of Art; the landscape is lifted verbatim from Dürer's Masonna with a Monkey of 1499 (Mayer 1937:`94).

- "Campagnola". Giornale Nuovo of things near & far. July 15, 2004. Archived from the original on 2006-10-10. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- Decker, Heinrich (1969) [1967]. The Renaissance in Italy: Architecture • Sculpture • Frescoes. New York: The Viking Press. pp. 157–58.

- Giulio Campagnola: Saint John the Baptist, Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts.

- General

- David Landau in Jane Martineau (ed), The Genius of Venice, 1500-1600, 1983, Royal Academy of Arts, London.

- Mark J Zucker in KL Spangeberg (ed), Six Centuries of Master Prints, Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993, nos 39 & 40, ISBN 0-931537-15-0

- W.R. Rearick in John Dixon Hunt (ed),The Pastoral Landscape, 1992, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Studies in the History of Art 36,ISBN 0-89468-181-8

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giulio Campagnola. |