German colonization of Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue

From 1850 to 1875, some 6,000 German immigrants settled in the region around Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue in Southern Chile as part of a state-led colonization scheme. Some of these immigrants had left Europe in the aftermath of the German revolutions of 1848–49. They brought skills and assets as artisans, farmers and merchants to Chile, contributing to the nascent country's economic and industrial development.

The German colonization of Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue is considered the first of three waves of German settlement in Chile, the second lasting from 1882 to 1914 and the third from 1918 onward.[1] Settlement by ethnic Germans has had a long-lasting influence on the society, economy and geography of Chile in general and Southern Chile in particular.

History

Early colonization

Beginning in 1842, German expatriate Bernhard Eunom Philippi sent a proposal for German colonization of Southern Chile to the Chilean government; he presented a second colonization scheme in 1844. Both schemes were rejected by Chilean authorities. The second scheme considered the colonization of both the shores of Llanquihue Lake and the mouth of the Maullín River in what is now the Los Lagos Region of southern Chile. The mentioned river was also to be made navigable.[2]

In 1844, Philippi formed a partnership with Ferdinand Flindt, a German merchant based in Valparaíso, who also represented Prussia there as consul. With financial backing from Flindt, Philippi purchased land in Valdivia and along the southern bank of the Bueno River to be developed by future immigrants. Philippi's brother, Rodolfo Amando Philippi, contributed to the colonization plans by recruiting nine German families to emigrate to Chile. These families arrived in Chile in 1846 aboard one of Flindt's ships. By the time the first immigrants arrived, Flindt had gone bankrupt and his properties were taken over by another German merchant, Franz Kindermann. Kindermann supported German immigration and took over Flindt's responsibilities.[2] Land purchases of dubious legality were made by Kindermann and his father-in-law Johann Renous around Trumao with the aim of re-selling these lands to German immigrants.[3] The bankrupt Flindt had made similar purchases near Osorno.[3] As the Chilean state nullified Kindermann's and Renous' purchases, the first immigrants to arrive were instead settled in Isla Teja in Valdivia, a river island then called Isla Valenzuela.[3]

State-sponsored colonization

Worried about the potential occupation of Southern Chile by European powers, Chilean authorities approved plans for colonization of the southern territories; they also sought to promote residential development to make a claim for territorial continuity.[4][5]

The Chilean legislature entered colonist recruitment with passage of the Law of Colonization and Vacant Lots (Ley de Colonización y Tierras Baldías), which was signed by president Manuel Montt in 1845.[5] That same year, Salvador Sanfuentes was appointed intendant of the Province of Valdivia and tasked with surveying its colonization potential. To carry out the survey, Sanfuentes commissioned Philippi as "provincial engineer".[2]

The outbreak of the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states persuaded the previously hesitant Philippi to travel to Europe to recruit settlers.[2][4] The Chilean government initially ordered Philippi to recruit 180–200 German Catholic families. Troubled by Catholic bishops in Germany who opposed the departure of their parishioners, Philippi asked for and was granted permission to recruit non-Catholic immigrants.[2] Philippi also succeeded in having the Chilean government put fixed prices on fiscal colonization land to stimulate immigration of economically independent individuals and avoid speculation. Most of the immigrants recruited by Philippi during his 1848–1851 stay in Germany were Protestant. The few Catholic families recruited were all poor people from Württemberg.[2]

The immigrants recruited by Philippi arrived in 1850 at Valdivia, where Vicente Pérez Rosales was declared colonization agent by the Chilean government.[6] One of the most notable early immigrants was Carl Anwandter, who settled in Valdivia in 1850 after having participated in the Revolution of 1848 in Prussia.[7] Most immigrants had their own economic means and were therefore free to settle where they wished. They settled mainly around Valdivia. The few Catholic families from Württemberg, who needed Chilean state support, could be allocated as the government wished. By 1850, this last group was too small to establish a functional German settlement at the shores of Llanquihue Lake as Philippi had envisioned. He instead decided to settle the Catholic families in the interior of Valdivia Province. Upon his return to Chile in 1851, Philippi was admonished by minister Antonio Varas for sending too many Protestant settlers.[upper-alpha 1] As punishment Philippi was appointed governor of Magallanes instead of being appointed leader of the future Llanquihue settlement as he wished. In Magallanes, Philippi was killed by indigenous people in 1852.[2]

We shall be honest and laborious Chileans as the best of them, we shall defend our adopted country joining in the ranks of our new countrymen, against any foreign oppression and with the decision and firmness of the man that defends his country, his family and his interests. Never will have the country that adopts us as its children, reason to repent of such illustrated, human and generous proceeding,...

Pérez Rosales succeeded Philippi as government agent in Europe in 1850; he returned to Chile in 1852 with many German families to settle the shores of Llanquihue Lake.[10]

The sponsored colonization of Valdivia and Osorno lasted until 1858.[11] The shores of Llanquihue Lake were largely colonized between 1852 and 1875, but Puerto Montt (then called Melipulli) and Puerto Varas had already been founded by Chileans in 1850.[11][12] Frutillar, on the shores of Llanquihue Lake, was founded in 1856.[12] Puerto Montt and the zone around Llanquihue Lake developed rapidly; its status as a colonization territory, established in 1853, was superseded in 1861 when the Llanquihue area was constituted as a regular province. The zone had a formal police force established in 1859 to deal with cattle theft – the most common crime at the time. By 1871, Puerto Montt had over 3,000 inhabitants and the whole Llanquihue Province had a population of 17,538.[13]

Valdivia, situated at some distance from the coast, on the Calle-Calle River, is a German town. Everywhere you meet German faces, German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish. There is a large German school, a church and various Vereine, large shoe-factories, and, of course, breweries...

Compared to Germans who settled in the big cities and ports of northern Chile, the Germans of southern Chile retained much of their German culture or Deutschtum. In time, communities came to develop a dual Chilean and German sense of belonging. Contrary to the fears of observers from the United States and as promoted by imperial and Nazi Germany, the German community in Chile did not act as an extension of the German state to any significant degree.[8] Indeed, settlement in Chile had little to do with the German state as most migration preceded the formation of modern Germany in 1871.[8]

Economic impact

Following independence in 1820, Valdivia entered a period of economic decline.[15] Since colonial times the city had been isolated from Central Chile by hostile Mapuche-controlled territory, and it depended heavily upon seaborne trade with the port of Callao in Peru.[15] With independence, this intra-colonial trade ended, but it was not replaced by new trade routes.[15]

About 6,000 Germans settlers arrived in southern Chile between 1850 and 1875. Of these, 2,800 settled around Valdivia. The plurality of those Germans settled in Valdivia came from Hesse (19%), and 45% of them had worked as artisans in Germany. The next largest occupation group were farmers (28%), followed by merchants (13%). Most German settlers who reached Valdivia brought current assets, including machinery or other valuable goods. Wealthy immigrants in Valdivia provided credit to poorer ones, stimulating the local economy.[15] The nature of the German immigrants to Valdivia contributed to the city's urban and cosmopolitan outlook, especially when compared to Osorno.[16]

At first, German settlements outside Valdivia were largely based on subsistence economies. As transportation developed, the settlers' economy shifted into one linked to national and international markets and based on the exploitation of natural resources, chiefly wood from the Valdivian temperate rainforests.[8] This became particularly egregious in the period after 1870, when improved roads made connection from the hinterland of Llanquihue Lake to the coast easy.[8] Germans and German-Chileans developed trade across the Andes, controlling mountain passes and establishing the settlement from which Bariloche in Argentina grew.[17]

In Osorno, German industrial activity declined in the 1920s at the same time that the city's economy turned towards cattle ranching.[18][16] With land ownership heavily concentrated among a few families, many indigenous Huilliche of Osorno became peasants of large estates (latifundia) owned by Germans.[16]

Among the achievements of the German immigrants was a deepening of the division of labour, the introduction of wage labour in agriculture, and the establishment of Chile's first beer brewery in Valdivia in 1851 by Carl Anwandter.[16][15] Some foreign observers made exaggerated accounts regarding the impact Germans had in local affairs; for example, Isaac F. Marcosson wrote in 1925 that Valdivia "was a collection of mud houses" before the arrival of Germans.[8]

Trade between Germans and German-Chileans with indigenous peoples was not uncommon. Indeed, some German merchants catered specifically to them.[16] For example, in San José de la Mariquina, Mapuches were the main customers of German shopkeepers.[16] A lucrative leather industry that Germans created was supplied by indigenous traders from across the Andes until the 1880s when the Argentine Army displaced indigenous communities.[17] The city of Bariloche in present-day Argentina grew out by a shop established by German-Chilean merchant Carlos Wiederhold.[17] Beginning with him, businessmen of German heritage brought in labourers from the Chiloé Archipelago to the Bariloche area.[17] German and German-Chilean enterprises in southwestern Argentina acted as brokers for both Chile and Argentina, assisting both nations in controlling traffic across the southern Andes.[17]

Relations with Mapuches and Chileans

Early German settlers had good relations with the indigenous Mapuche and Huilliche, in contrast to their more uneasy relations with the Spanish-descent elite of Valdivia, whom they considered lazy. A pamphlet published in Germany by Franz Kindermann to attract immigrants states that while neither Chileans (meaning those of Spanish descent) nor the Mapuche liked to work, the latter were honest.[16]

the indians [...] that live next to us are absolutely pacific and inoffensive people, with who we have a better dealing than with the Chileans of Spanish origin

It is worth noting that according to Rodolfo Amando Philippi, in the 1850s the inhabitants of Valdivia did not considered themselves Chileans, as tp them Chile lay further north.[19] German-indigenous relations chilled over time. This had to do with the Germans becoming the new European social elite of southern Chile and their adoption of some customs of the older Spanish-descent elite. Another reason for the soured relations was that German immigrants and their descendants became involved in land ownership conflicts with Huilliche, Mapuche and other Chileans.[16]

Land conflicts aside some Chilean intellectuals did also became critical of the German community in Chile. Chilean minister Luis Aldunate considered that Germans integrated poorly and that the country should avoid "exclusive and dominant races that monopolize the colonization".[20] For this reason after the Occupation of Araucanía was accomplished in 1883 settlers of nationalities other than Germans were preferred in colonization programs.[20] According to Chile's Agencia General de Colonización in the 1882-1897 period German settlers made up only 6% of the foreign immigrants that arrived to Chile, ranking behind those of Spanish, French, Italian, Swiss and English origin.[21]

The Huilliche called the German settlers leupe lonko meaning blond heads.[19]

Land ownership conflicts

As German colonization expanded into new areas beyond the designated colonization areas, such as the coastal region of Osorno and some Andean lakes and valleys, settlers began to have conflicts with indigenous peoples. The Chilean state ignored laws that protected indigenous property, in some instances purportedly because people who were Christian and literate could not be considered indigenous.[16]

The Sociedad Stuttgart, a society established to bring German settlers to Chile, had one of the first major conflicts.[22][23] In 1847 and 1848, this society purchased about 15,000 km2 under fraudulent conditions from Huilliche west of Osorno.[22][23] The Chilean government objected to these purchases but the transactions were ratified in Chilean courts.[16]

Huilliches found various difficulties to defend their lands. One of them was a language barrier and had thus to rely on translators some of which were scammers.[19] The functions of the Comisario de Naciones were overtaken by ordinary judges in mid-19th century who were not aware of indigenous land possesions.[19]

As a result of Chilean and European settlers, including Germans, settling around the Bueno River, Osorno Huilliches living in the Central Valley migrated to the coastal region of Osorno.[22]

German seizure of lands in the south of the Mapuche territory was one of the factors that led chief Mañil in 1859 to call for an uprising to assert control over the territory.[24] According to Mañil, the Chilean government had granted Mapuche land to the immigrants, although it was not under national control.[16] The southern Mapuche communities near the German settlers did not respond to Mañil's efforts to create unrest.[16] Mañil's uprising did provoke a decision by Chilean authorities to conquer the Mapuche in Araucanía; this in turn opened more land for European and Chilean colonization,[upper-alpha 2] at the expense of the Mapuche.[24]

In the 20th century two members of the Grob family linked to dairy company COLUN have been accused of usurpation of land and being behind the violent eviction of Mapuche-Huilliche around Ranco Lake.[26] In the Ranco area a conflict known as "La guerra de los moscos" around 1970 marked the end of loss of land for Mapuche-Huilliche families.[26] Following an extensive legal study on the origin of property a legal case was presented in Chilean courts for the recovery of these lands in 2012.[26][27]

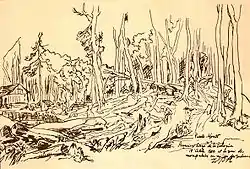

Forest fires and volcanic eruptions

Vicente Pérez Rosales burned down huge tracts of forested lands to clear lands for the settlers.[6] In 1851 the forest of Chan Chan between Osorno and La Unión were burned by Pichi Juan on the orders of Pérez Rosales.[28][29] Another area affected by these fires spanned a strip in the Andean foothills from the Bueno River to Reloncaví Sound.[6][upper-alpha 3] One of the most famous intentional fires burned the Fitzroya forests between Puerto Varas and Puerto Montt in 1863.[31] This burning took advantage of a drought in 1863.[31] The forests were burned to clear them rapidly for settlers, who had no means of subsistence other than agriculture.[31]

In 1893, Calbuco volcano erupted, disrupting the daily life of the settlers in eastern Llanquihue Lake. In this area, potato fields, cattle and apiculture was negatively impacted by the eruption, which lasted until 1895. Cattle was evacuated from the area and settlers lobbied the government of Jorge Montt to be relocated elsewhere.[32]

Linguistic legacy

The impact of the German immigration was such that Valdivia was for a while a Spanish–German bilingual city with "German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish".[14] The prestige[upper-alpha 4] of the German language helped it to acquire qualities of a superstratum in southern Chile.[1] The temporary decline in the use of Spanish is exemplified by the trade the Manns family carried out in the second half of the 19th century. The family's Chilean servants spoke German with their patrons and used Mapudungun with their Mapuche customers.[16]

The word for blackberry, an ubiquitous plant in southern Chile, is murra instead of the ordinary Spanish word mora and zarzamora from Valdivia to the Chiloé Archipelago and some towns in the Aysén Region.[1] The use of rr is an adaptation of guttural sounds found in German but difficult to pronounce in Spanish.[1] Similarly the name for marbles is different in Southern Chile compared to areas further north. From Valdivia to the Aysén Region, this game is called bochas contrary to the word bolitas used further north.[1] The word bocha is likely derivative of the Germans bocciaspiel.[1]

Notes

- In this way, Germany's Protestant–Catholic divide was brought to Chile.[8]

- When the territory of Araucanía was subdued the Chilean government issued calls for immigration in Europe. The most numerous groups of settlers were the Italians who settled mainly around Lumaco, the Swiss who colonized Traiguén and Boers who settled mainly around Freire and Pitrufquén. Other settler nationalities included Englishmen, French people and Germans. There are estimates that by 1886 there were 3,501 foreign settlers in Araucanía, another investigation points out that 5,657 foreign settlers arrived to Araucanía in the 1883–90 period.[25] Regarding Chilean settlers these arrived first to Araucanía by their own initiative. Later the government begun to stimulate the settlement of Chileans in Araucanía. Chilean settlers were mostly poor and largely remained so in their new lands.[25]

- This was not the first instance where Fitzroya forest burned. Some localities have a long history of repeated fires, for instance dendrochronological studies shows at Cordillera Pelada a sequence of Fitzroya forest fires dating as far back as 1397.[30]

- Germany's prestige was reflected in efforts by Chileans to bring German knowledge to Chile in the late 19th century. Institutions like the Chilean Army and Instituto Pedagógico were heavily influenced by Germany. Germany effectively displaced France as the prime role model for Chile in the second half of the 19th century. This however met some criticism as exemplified when Eduardo de la Barra wrote disparagingly about a "German bewitchment". German influence in science and culture peaked in the decades before World War I.[33]

References

- Wagner, Claudio (2000). "Las áreas de "bocha", "polca" y "murra". Contacto de lenguas en el sur de Chile". Revista de Dialectología y Tradiciones Populares (in Spanish). LV (1): 185–196. doi:10.3989/rdtp.2000.v55.i1.432.

- George F. W., Young (1971), "Bernardo Philippi, Initiator of German Colonization in Chile", The Hispanic American Historical Review, 51 (3): 478–496, doi:10.2307/2512693, JSTOR 2512693

- Anwandter, Carl. González Cangas, Yanko (ed.). Desde Hamburgo a Corral: Diario de Viaje a Bordo del Velero Hermann (in Spanish). Translated by Weil G., Karin (2017 ed.). Ediciones Universidad Austral de Chile.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 456.

- Otero 2006, p. 79.

- Villalobos et al. 1974, p. 457.

- "Carlos Anwandter", Icarito, archived from the original on December 17, 2013, retrieved August 30, 2013

- Penny, H. Glenn (2017). "Material Connections: German Schools, Things, and Soft Power in Argentina and Chile from the 1880s through the Interwar Period". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 59 (3): 519–549. doi:10.1017/S0010417517000159. Retrieved December 13, 2018.

- Pérez Rosales, Vicente. (1882) 1970. Recuerdos del pasado (1814-1860). Buenos Aires: Editorial Francisco de Aguirre.

- "Colonización alemana en Valdivia y Llanquihue (1850-1910)", Memoria chilena (in Spanish), retrieved November 30, 2013

- Otero 2006, p. 80.

- Otero 2006, p. 81.

- Barhm G., Enrique (2014). "La Consolidación de una Colonia en la Patagonia Occidental: Chilenos y Alemanes en Torno a la Creación de la Provincia de Llanquihue (Capital Perto Montt, Chile)". Magallania (in Spanish). 42 (1). Retrieved 24 July 2015.

- Skottsberg, Carl (1911), The Wilds of Patagonia: A Narrative of the Swedish Expedition to Patagonia Tierra del Fuego and the Falkland Island in 1907- 1909, London: Edward Arnold

- Bernedo Pinto, Patricio (1999), "Los industriales alemanes de Valdivia, 1850-1914" (PDF), Historia (in Spanish), 32: 5–42

- Vergara, Jorge Iván; Gundermann, Hans (2012). "Constitution and internal dynamics of the regional identitary in Tarapacá and Los Lagos, Chile". Chungara (in Spanish). University of Tarapacá. 44 (1): 115–134. doi:10.4067/s0717-73562012000100009. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Muñoz Sougarret, Jorge (2014). "Relaciones de dependencia entre trabajadores y empresas chilenas situadas en el extranjero. San Carlos de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)" [Dependence Relationships between Workers and Chilean Companies located abroad. San Car-los de Bariloche, Argentina (1895-1920)]. Trashumante: Revista Americana de Historia Social (in Spanish). 3: 74–95. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- "Osorno (1558-1950)", Memoria chilena (in Spanish), retrieved November 30, 2013

- Rumian Cisterna, Salvador (2020-09-17). Gallito Catrilef: Colonialismo y defensa de la tierra en San Juan de la Costa a mediados del siglo XX (M.Sc. thesis) (in Spanish). University of Los Lagos.

- Cayuqueo 2020, p. 243.

- Cayuqueo 2020, p. 244.

- Concha Mathiesen, Martín (1998). Una mirada a la identidad de los grupos huilliche de San Juan de la Costa (Thesis). Universidad Arcis.

- Yánez Fuenzalida, Nancy; Castillo-Candanedo, Jairo Gabriel; Barros Jiménez, Juan Sebastián; Ghio Madrid, Gina; Alvarado Borgoño, Miguel; Gaete Jodre, Silvia (2003), Investigación Evaluativa de Impacto Ambiental en Territorios Indígenas (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2013, retrieved December 27, 2013

- Bengoa, José (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche: Siglos XIX y XX (Seventh ed.). LOM Ediciones. pp. 166–170. ISBN 956-282-232-X.

- Pinto Rodríguez, Jorge (2003). La formación del Estado y la nacion, y el pueblo mapuche (Second ed.). Ediciones de la Dirección de Bibliotecas, Archivos y Museos. pp. 217 and 225. ISBN 956-244-156-3.

- Carrasco S., Carlos (September 3, 2018). "La historia no contada de COLUN: Los Grob y las Tierras Williche". futawillimapu.org (in Spanish). Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Morales S., Héctor (April 14, 2012). "Acogen demanda histórica por reivindicación de tierras en Lago Ranco". El Ranco (in Spanish). Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Camus, Pablo; Solarí, María Eugenia (2008). "La invención de la selva austral. Bosques y tierras despejadas en la cuenca del río Valdivia (siglos XVI-XIX)". Revista de Geografía Norte Grande (in Spanish). 40: 5–22. doi:10.4067/S0718-34022008000200001.

- Cayuqueo 2020, p. 232-233

- Lara, A.; Fraver, S.; Aravena, J.C.; Wolodarsky-Franke, F. (1999), "Fire and the dynamics of Fitzroya cupressoides (alerce) forests of Chile's Cordillera Pelada", Écoscience, 6 (1): 100–109, doi:10.1080/11956860.1999.11952199, archived from the original on 2014-08-27

- Otero 2006, p. 86.

- Petit-Breuilh Sepúlveda, María Eugenia (2004). La historia eruptiva de los volcanes hispanoamericanos (Siglos XVI al XX): El modelo chileno (in Spanish). Huelva, Spain: Casa de los volcanes. p. 59. ISBN 84-95938-32-4.

- Sanhueza, Carlos (2011). "El debate sobre "el embrujamiento alemnán" y el papel de la ciencia alemana hacia fines del siglo XIX en Chile" (PDF). Ideas viajeras y sus objetos. El intercambio científico entre Alemania y América austral. Madrid–Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana–Vervuert (in Spanish). pp. 29–40.

Bibliography

- Cayuqueo, Pedro (2020). Historia secreta mapuche 2 (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Catalonia. ISBN 978-956-324-783-1.

- Otero, Luis (2006). La huella del fuego: Historia de los bosques nativos. Poblamiento y cambios en el paisaje del sur de Chile (in Spanish). Pehuén Editores. ISBN 956-16-0409-4.

- Villalobos R., Sergio; Silva G., Osvaldo; Silva V., Fernando; Estelle M., Patricio (1974). Historia de Chile (in Spanish) (1995 ed.). Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 956-11-1163-2.