George Pullman

George Mortimer Pullman (March 3, 1831 – October 19, 1897) was an American engineer and industrialist. He designed and manufactured the Pullman sleeping car and founded a company town, Pullman, for the workers who manufactured it. This ultimately led to the Pullman Strike due to the high rent prices charged for company housing and low wages paid by the Pullman Company. His Pullman Company also hired African-American men to staff the Pullman cars, who became known as Pullman porters, providing elite service.

George Pullman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Mortimer Pullman March 3, 1831 |

| Died | October 19, 1897 (aged 66) |

| Occupation | Engineer/Industrialist |

| Net worth | USD $17.5 million at the time of his death (approximately 1/835th of US GNP)[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Hattie Amelia Sanger (1843–1922) |

| Children | 4 |

| Parent(s) | James Lewis Pullman (1800–1852) Emily Caroline Minton (1808–1892) |

| Relatives | Florence (1868–1937) (daughter) Harriett (1869–1956) (daughter) {twin} George (1876–1901) (son) {twin} Walter Sanger (1876–1905)(son) |

| Signature | |

| |

Struggling to maintain profitability during an 1894 downturn in manufacturing demand, he halved wages and required workers to spend long hours at the plant, but did not lower prices of rents and goods in his company town. He gained presidential support by Grover Cleveland for the use of federal military troops which left 30 strikers dead in the violent suppression of workers there to end the Pullman Strike of 1894. A national commission was appointed to investigate the strike, which included assessment of operations of the company town. In 1898, the Supreme Court of Illinois ordered the Pullman Company to divest itself of the town, which became a neighborhood of the city of Chicago.

Early life

Pullman was born in 1831 in Brocton, New York, the son of Emily Caroline (Minton) and carpenter James Lewis Pullman.[2] His family moved to Albion, New York, along the Erie Canal in 1845, so his father could help widen the canal. His father had invented a machine using jackscrews that could move buildings or other structures out of the way and onto new foundations and had patented it in 1841. By that time, packet boats carried people on day excursions along the canal, plus travellers and freight craft would be towed across the state along the busy canal.

Pullman attended local schools and helped his father, learning other skills that contributed to his later success. He dropped out of school. In 1855, his father died.

Career

Pullman was a clerk for a country merchant. Pullman took over the family business. In 1856, Pullman won a contract with the State of New York to move 20 buildings out of the way of the widening canal.

Chicago

In 1857, as a young engineer, Pullman arrived in Chicago, Illinois as the city prepared to build the nation's first comprehensive sewer system. Pullman formed a partnership known as Ely, Smith & Pullman. Chicago was built on a low-lying bog, and people described the mud in the streets as deep enough to drown a horse.[3] The growing city needed a sewer system, and Pullman's became one of several companies hired to lift multi-story buildings four to six feet—to both allow sewers to be constructed and to improve the foundations. The project would involve effectively raising the street level 6–8 feet, first constructing the sewers at ground level, then covering them.[4] The Ely, Smith & Pullman partnership gained favorable publicity for raising the massive Tremont House, a six-story brick hotel, while the guests remained inside.[5]

Pullman sleeping car

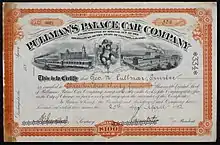

Pullman developed a railroad sleeping car, the Pullman sleeper or "palace car." These were designed after the packet boats that travelled the Erie Canal of his youth in Albion. The first one was finished in 1864.

After President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, Pullman arranged to have his body carried from Washington, D.C. to Springfield on a sleeper, for which he gained national attention, as hundreds of thousands of people lined the route in homage. Lincoln's body was carried on the Presidential train car that Lincoln himself had commissioned that year. Pullman had cars in the train, notably for the President's surviving family. The pullman had a wider wheel set, requiring wider track. And as a result of the many people seeing the Palace car, it became sought after and resulted in a major change to all rail track widths. Orders for his new car began to pour into his company. The sleeping cars proved successful although each cost more than five times the price of a regular railway car. They were marketed as "luxury for the middle class."

In 1867, Pullman introduced his first "hotel on wheels," the President, a sleeper with an attached kitchen and dining car. The food rivaled the best restaurants of the day and the service was impeccable. A year later in 1868, he launched the Delmonico, the world's first sleeping car devoted to fine cuisine. The Delmonico menu was prepared by chefs from New York's famed Delmonico's Restaurant.

Both the President and the Delmonico and subsequent Pullman sleeping cars offered first-rate service. The company hired African-American freedmen as Pullman porters. Many of the men had been former domestic slaves in the South. Their new roles required them to act as porters, waiters, valets, and entertainers, all rolled into one person.[6] As they were paid relatively well and got to travel the country, the position became considered prestigious, and Pullman porters were respected in the black communities.

Pullman believed that if his sleeper cars were to be successful, he needed to provide a wide variety of services to travelers: collecting tickets, selling berths, dispatching wires, fetching sandwiches, mending torn trousers, converting day coaches into sleepers, etc. Pullman believed that former house slaves of the plantation South had the right combination of training to serve the businessmen who would patronize his "Palace Cars." Pullman became the biggest single employer of African Americans in post-Civil War America.[6]

In 1869, Pullman bought out the Detroit Car and Manufacturing Company. Pullman bought the patents and business of his eastern competitor, the Central Transportation Company in 1870. In the spring of 1871, Pullman, Andrew Carnegie, and others bailed out the financially troubled Union Pacific; they took positions on its board of directors. By 1875, the Pullman firm owned $100,000 worth of patents, had 700 cars in operation, and had several hundred thousand dollars in the bank.

In 1887, Pullman designed and established the system of "vestibuled trains," with cars linked by covered gangways instead of open platforms. The vestibules were first put in service on the Pennsylvania Railroad trunk lines.[7] The French social scientist Paul de Rousiers (1857–1934), who visited Chicago in 1890, wrote of Pullman's manufacturing complex, "Everything is done in order and with precision. One feels that some brain of superior intelligence, backed by a long technical experience, has thought out every possible detail."[8]

Pullman company town

In 1880, Pullman bought 4,000 acres (16 km2), near Lake Calumet some 14 mi (23 km) south of Chicago, on the Illinois Central Railroad for $800,000. Pullman hired Solon Spencer Beman to design his new plant there. Trying to solve the issue of labor unrest and poverty, he also built a company town adjacent to his factory; it featured housing, shopping areas, churches, theaters, parks, hotel and library for his factory employees. The 1300 original structures were entirely designed by Solon Spencer Beman. The centerpiece of the complex was the Administration Building and a man-made lake. The Hotel Florence, named for Pullman's daughter, was built nearby.

Pullman believed that the country air and fine facilities, without agitators, saloons and city vice districts, would result in a happy, loyal workforce. The model planned community became a leading attraction for visitors who attended the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893. It attracted nationwide attention. The national press praised Pullman for his benevolence and vision. According to mortality statistics, it was one of the most healthful places in the world.[7]

The industrialist still expected the town to make money as an enterprise. By 1892, the community, profitable in its own right, was valued at over $5 million. Pullman ruled the town like a feudal baron. Pullman prohibited independent newspapers, public speeches, town meetings or open discussion. His inspectors regularly entered homes to inspect for cleanliness and could terminate workers' leases on ten days' notice. The church stood empty since no approved denomination would pay rent, and no other congregation was allowed. He prohibited private charitable organizations. In 1885 Richard Ely wrote in Harper's Weekly that the power exercised by Otto Von Bismarck (known as the unifier of modern Germany), was "utterly insignificant when compared with the ruling authority of the Pullman Palace Car Company in Pullman." [9]

We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell.

— Some alleged Pullman employees living in the Pullman-owned town[10]

The Pullman community is a historic district that has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Marktown, Indiana, Clayton Mark's planned worker community, was developed nearby.[11]

Pullman strike

In 1894, when manufacturing demand fell off, Pullman cut jobs and wages and increased working hours in his plant to lower costs and keep profits, but he did not lower rents or prices in the company town. The workers eventually launched a strike. When violence broke out, he gained the support of President Grover Cleveland for the use of United States troops. Cleveland sent in the troops, who harshly suppressed the strike in action that caused many injuries, over the objections of the Illinois governor, John Altgeld.

In the winter of 1893–94, at the start of a depression, Pullman decided to cut wages by 30%. This was not unusual in the age of the robber barons, but he didn't reduce the rent in Pullman, because he had guaranteed his investors a 6% return on their investments in the town. A workman might make $9.07 in a fortnight, and the rent of $9 would be taken directly out of his paycheck, leaving him with just 7 cents to feed his family. One worker later testified: "I have seen men with families of eight or nine children crying because they got only three or four cents after paying their rent." Another described conditions as "slavery worse than that of Negroes of the South."

On May 12, 1894 the workers went on strike.

The American Railway Union was led by Eugene Victor Debs, a pacifist and socialist who later founded the Socialist Party of America and was its candidate for president in five elections. Under the leadership of Debs, sympathetic railroad workers across the nation tied up rail traffic to the Pacific. The so-called "Debs Rebellion" had begun.

Arcade Building with strikers and soldiers Debs gave Pullman five days to respond to the union demands but Pullman refused even to negotiate (leading another industrialist to yell, "The damned idiot ought to arbitrate, arbitrate and arbitrate! ...A man who won't meet his own men halfway is a God-damn fool!"). Instead, Pullman locked up his home and business and left town.

On June 26, all Pullman cars were cut from trains. When union members were fired, entire rail lines were shut down, and Chicago was besieged. One consequence was a blockade of the federal mail, and Debs agreed to let isolated mail cars into the city. Rail owners mixed mail cars into all their trains however, and then called in the federal government when the mail failed to get through.

Debs could not pacify the pent-up frustrations of the exploited workers, and violence broke out between rioters and the federal troops that were sent to protect the mail. On July 8, soldiers began shooting strikers. That was the beginning of the end of the strike. By the end of the month, 34 people had been killed, the strikers were dispersed, the troops were gone, the courts had sided with the railway owners, and Debs was in jail for contempt of court.

Pullman's reputation was soiled by the strike, and then officially tarnished by the presidential commission that investigated the incident. The national commission report found Pullman's paternalism partly to blame and described Pullman's company town as "un-American." The report condemned Pullman for refusing to negotiate and for the economic hardships he created for workers in the town of Pullman. "The aesthetic features are admired by visitors, but have little money value to employees, especially when they lack bread." The State of Illinois filed suit, and in 1898, the Supreme Court of Illinois forced the Pullman Company to divest ownership in the town, which was annexed to Chicago.[12][13]

Personal life

On October 19, 1897, Pullman died of a heart attack in Chicago, Illinois. He was 66 years old. Pullman was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago, Illinois.[14] George and his wife Hattie had four children: Florence, Harriett, George Jr. and Walter Sanger Pullman.

Burial

Fearing that some of his former employees or other labor supporters might try to dig up his body, his family arranged for his remains to be placed in a lead-lined mahogany coffin, which was then sealed inside a block of concrete. At the cemetery, a large pit had been dug at the family plot. At its base and walls were 18 inches of reinforced concrete. The coffin was lowered, and covered with asphalt and tarpaper. More concrete was poured on top, followed by a layer of steel rails bolted together at right angles, and another layer of concrete. The entire burial process took two days. His monument, featuring a Corinthian column flanked by curved stone benches, was designed by Solon Spencer Beman, the architect of the company town of Pullman.[15]

Scottish Rite

Pullman was initiated to the Scottish Rite Freemasonry in the Renovation Lodge No. 97, Albion, New York[16][17] until he raised the 33rd and highest degree.[18]

Public projects

Pullman was identified with various public enterprises, among them the Metropolitan elevated railway system of New York. It was constructed and opened to the public by a corporation of which he was president.[7]

The Pullman Company merged in 1930 with Standard Steel Car Company to become Pullman-Standard, which built its last car for Amtrak in 1982. After delivery the Pullman-Standard plant stayed in limbo, and eventually shut down. In 1987, its remaining assets were absorbed by Bombardier.

Legacy

- In Pullman's will, he bequeathed $1.2 million [19] to establish the Pullman Free School of Manual Training for the children of employees of the Pullman Palace Car Company and the residents of the neighboring Roseland community. In 1950, the George M. Pullman Educational Foundation succeeded the Pullman Free School of Manual Training, also known as Pullman Tech, after it closed its doors in 1949. Located in Chicago, Illinois, the George M. Pullman Educational Foundation supports college-bound high school seniors with merit-based, need-based scholarships to attend the college of their choice. Since its founding, the Foundation has awarded approximately $30 million to over 13,000 outstanding Cook County students.

- The city of Pullman, Washington is named in his honor. The town expected him to build major railroads in Pullman, but the route went into Spokane.

- The Pullman Memorial Universalist Church (1894) in Albion, New York, was funded and built by Pullman in memory of his parents.

See also

- Pullman porter

- Pullman, Chicago

- The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, organized after Pullman's death, was a leading African-American union.

References

- Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xiii, ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8, OCLC 33818143

- http://www.pullman-museum.org/theMan/

- A common expression describing a need for drainage as applied in Brooklyn.

- Randall J. Soland, Utopian Communities of Illinois: Heaven on the Prairie (History Press 2017) p. 99

- Chicago Daily Tribune, January 22, 1861 Archived May 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. nike-of-samothrace.net. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

- Lawrence Tye (2011-05-05). "Choosing Servility To Staff America's Trains | Alicia Patterson Foundation". Aliciapatterson.org. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- Miller, Donald L. (1997-04-03), City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America, Simon and Schuster, p. 235, ISBN 978-0-684-83138-1, retrieved 2017-07-09

- "The Parable of Pullman". Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved 2011-08-28.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Kent Law Journal, 2008

- The Town of Pullman. pullman-museum.org

- Smith, S. & Mark, S. (2011). "Marktown: Clayton Mark's Planned Worker Community in Northwest Indiana", South Shore Journal, 4. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2012-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/chicago/peopleevents/p_pullman.html

- Arthur Melville Pearson (January–February 2009). "Utopia Derailed". Archaeology. 62 (1): 46–49. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- "George Mortimer Pullman". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- "Chicago Remains to Be Seen - George Pullman". Cemeteryguide.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Famous men members of Masonic Lodges". American Canadian Grand Lodge ACGL. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- "Famous members of Masonic Lodges". Bavaria Lodge No. 935 A.F. & A. M. Archived from the original on October 13, 2018.

- "Information about famous members of Freemasonry". Scottish Rite Center (Columbus, Orient of Georgia). Archived from the original on September 30, 2014.

- "George M. Pullman's Will". New York Times. 28 October 1897. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

Further reading

- Dwyer, Michael Middleton. Carolands. Redwood City, CA: San Mateo County Historical Association, 2006. ISBN 0-9785259-0-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Pullman. |