George Psalmanazar

George Psalmanazar (c. 1679 – 3 May 1763) was a Frenchman who claimed to be the first native of Formosa (today Taiwan) to visit Europe. For some years he convinced many in Britain, but he was later revealed to be an impostor and proved fake. He subsequently became a theological essayist, and a friend and acquaintance of Samuel Johnson and other noted figures in 18th-century literary London.

George Psalmanazar | |

|---|---|

George Psalmanazar (1679–1763) | |

| Born | c. 1679 – 1684 South France |

| Died | 3 May 1763 England |

| Occupation | Memoirist, imposter |

| Known for | Formosa culture fake memoir |

Early life

Although Psalmanazar intentionally obscured many details of his early life, it is believed that he was born in southern France, perhaps in Languedoc or Provence, to Catholic parents, some time between 1679 and 1684.[1][2] His birth name is unknown.[1] According to his posthumously published autobiography, he was educated in a Franciscan school and then a Jesuit academy. In both these institutions he claimed to have been celebrated by his teachers for what he called "my uncommon genius for languages".[3] Indeed, by his own account Psalmanazar was something of a child prodigy. He claims that he attained fluency in Latin by the age of seven or eight, and excelled in competition with children twice his age. Later encounters with a sophistic philosophy tutor made him disenchanted with academicism, however, and he discontinued his education around the time he was fifteen or sixteen.[2]

Career as an impostor

Continental Europe

In order to travel safely and affordably in France, Psalmanazar decided to pretend to be an Irish pilgrim on his way to Rome. After learning English, forging a passport, and stealing a pilgrim's cloak and staff from the reliquary of a local church he set off, but he soon found that many people he met were familiar with Ireland and were able to discern that he was a fraud.[4] Deciding that a more exotic disguise was needed, Psalmanazar drew upon the missionary reports about East Asia that he had heard of from his Jesuit tutors and decided to impersonate a Japanese convert. At some point he further embellished this new persona by pretending to be a "Japanese heathen" and exhibiting an array of appropriately bizarre customs, such as eating raw meat spiced with cardamom and sleeping while sitting upright in a chair.

Having failed to reach Rome, Psalmanazar travelled through various German principalities between 1700 and 1702. In the latter year he appeared in the Netherlands, where he served as an occasional mercenary and soldier. By this time he had shifted his supposed homeland from Japan to the even more remote Formosa (Taiwan), and had developed more elaborate customs, such as following a foreign calendar, worshipping the Sun and the Moon with complex propitiatory rites of his own invention, and even speaking an invented language.

In late 1702 Psalmanazar met the Scottish priest Alexander Innes, who was the chaplain of a Scottish army unit. Afterwards Innes claimed that he had converted the heathen to Christianity and christened him George Psalmanazar (after the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V, who is referenced in the Bible). In 1703 they left via Rotterdam for London, where they planned to meet Anglican clergymen.

England

When they reached London news of the exotic foreigner with bizarre habits spread quickly and Psalmanazar achieved a high level of fame. His appeal not only derived from his exotic ways, which tapped into a growing domestic interest in travel narratives describing faraway locales, but also played upon the prevailing anti-Catholic and anti-Jesuit religious sentiment of early 18th century Britain. Central to his narrative was his claim to have been abducted from Formosa by malevolent Jesuits and taken to France, where he had steadfastly refused to become a Catholic. Psalmanazar declared himself to be a reformed heathen who now practised Anglicanism. He became a favourite of the Bishop of London and other esteemed members of London society.[5]

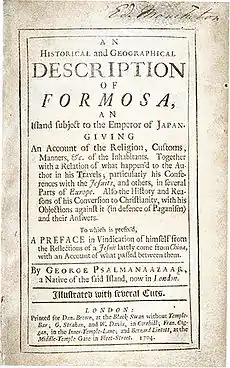

Building upon this growing interest in his life, in 1704 Psalmanazar published a book, An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, an Island subject to the Emperor of Japan, which purported to be a detailed description of Formosan customs, geography and political economy, but which was in fact a complete invention. The "facts" contained in the book are an amalgam of other travel reports, especially influenced by accounts of the Aztec and Inca civilisations in the New World, and by embellished descriptions of Japan. Thomas More's Utopia may also have served as an inspiration. Some of his claims about Japanese religion seem to also be derived from a misinterpretation of the Chinese idea of three teachings, as he claims that there were three different forms of "idolatry" practiced in Japan.[6]

According to Psalmanazar, Formosa was a prosperous country with a capital city called Xternetsa. Men walked naked except for a gold or silver plate to cover their genitals. Their main food was a serpent that they hunted with branches. Formosans were polygamous and husbands had a right to eat their wives for infidelity. They executed murderers by hanging them upside down and shooting them full of arrows. Every year they sacrificed the hearts of 18,000 young boys to gods, and their priests ate the bodies. They used horses and camels for transport, and dwelled underground in circular houses.

Pseudo-lexicographer

Psalmanazar's book also described the Formosan language, an early example of a constructed language. His efforts in this regard were so convincing that German grammarians included samples of his so-called "Formosan alphabet" in books about language well into the 19th century, even after his larger imposture had been exposed. Here is his "translation" of the Lord's Prayer:

Amy Pornio dan chin Ornio vicy, Gnayjorhe sai Lory, Eyfodere sai Bagalin, jorhe sai domion apo chin Ornio, kay chin Badi eyen, Amy khatsada nadakchion toye ant nadayi, kay Radonaye ant amy Sochin, apo ant radonern amy Sochiakhin, bagne ant kau chin malaboski, ali abinaye ant tuen Broskacy, kens sai vie Bagalin, kay Fary, kay Barhaniaan chinania sendabey. Amien.

Psalmanazar's book was an unqualified success. It went through two English editions, and French and German editions followed. After its publication Psalmanazar was invited to lecture on Formosan culture and language before several learned societies, and it was even proposed that he be summoned to lecture at the University of Oxford. In the most famous of these engagements he spoke before the Royal Society, where he was challenged by Edmond Halley.

Psalmanazar was frequently challenged by sceptics, but for the most part he managed to deflect criticism of his core claims. He explained, for instance, that his pale skin was due to the fact that the upper classes of Formosa lived underground. Jesuits who had actually worked as missionaries in Formosa were not believed, probably because of anti-Jesuit prejudice.

Later life

Chaplain and theological essayist

Innes eventually went to Portugal as chaplain general to the British forces. By then, however, he had developed an opium addiction and had become involved in several misguided business ventures, including a failed effort to market decorated fans purported to be from Formosa. Psalmanazar's claims became increasingly less credible as time went on and knowledge of Formosa from other sources began to contradict his claims. His energetic defence of his imposture began to slacken and in 1706 he confessed, first to friends and then to the general public. By then London society had largely grown tired of the "Formosan craze".

In the following years Psalmanazar worked for a time as a clerk in an army regiment until some clergymen gave him money to study theology. Psalmanazar then participated in the literary milieu of Grub Street, writing pamphlets, editing books and undertaking other low-paid and unglamorous tasks. He learned Hebrew, co-authored Samuel Palmer's A General History of Printing (1732), and contributed a number of articles to the Universal History. He even contributed to A Complete System of Geography and wrote about the real conditions in Formosa, pointedly criticising the hoax he himself had perpetrated.[7] He appears to have become increasingly religious and disowned his youthful impostures. This newfound religiosity culminated in his anonymous publication of a book of theological essays in 1753.

Friend of Samuel Johnson and others

Although this last phase of Psalmanazar's life brought him far less fame than his earlier career as a fraud, it resulted in some remarkable historical coincidences. Perhaps the most famous of these is the elderly Psalmanazar's unlikely friendship with the young Samuel Johnson, who was also a Grub Street hack. In later years Johnson recalled that Psalmanazar had been well-known in his neighbourhood as an eccentric but saintly figure, "whereof he was so well known and esteemed, that scarce any person, even children, passed him without showing him signs of respect".[8]

Psalmanazar also interacted with a number of other important English literary figures of his age. In the early months of 1741 he appears to have sent the novelist Samuel Richardson an unsolicited bundle of forty handwritten pages in which he attempted to continue the plotline of Richardson’s immensely popular epistolary novel Pamela. Richardson called Psalmanazar's attempted sequel "ridiculous and improbable".[9] In "A Modest Proposal" Jonathan Swift ridicules Psalmanazar in passing, sardonically citing "the famous Salamanaazor, a Native of the island of Formosa, who came from thence to London, above twenty Years ago," as an eminent proponent of cannibalism.[10] A novel by Tobias Smollett refers mockingly to "Psalmanazar, who, after having drudged half a century in the literary mill in all the simplicity and abstinence of an Asiatic, subsists on the charity of a few booksellers, just sufficient to keep him from the parish".[11]

Death and memoirs

In old age Psalmanazar lived on an annual pension of £30, paid by an admirer.[12] In his last years he wrote his Memoirs of ** **, Commonly Known by the Name of George Psalmanazar; a Reputed Native of Formosa. The book, which was published posthumously, withholds his real birth name, which is still unknown, but contains a wealth of detail about his early life and the development of his impostures.

References

- George Psalmanazar: the Celebrated Native of Formosa by the Special Collections Department of University of Delaware Library. Last modified 3 November 2003. Accessed 3 November 2003.

- The Native of Formose by Alex Boese. Museum of Hoaxes. Last modified 2002. Accessed 3 November 2003.

- George Psalmanazar, Memoirs, London, 1764, pg. 79

- Orientalism as Performance Art Archived 29 January 2012 at WebCite by Jack Lynch. Delivered 29 January 1999 at the CUNY Seminar on Eighteenth-Century Literature. Accessed 2007 – 3–11.

- "GReat Hoaxes of History". The Pittsburgh Press. 18 January 1910.

- Josephson, Jason (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 14-15.

- George Psalmanazar, Memoirs, London, 1764, pg. 339

- Foley, Frederic J., The Great Formosan Impostor. New York: Privately printed, 1968, p. 65

- Foley 53

- Davis, Lennard J. Factual Fictions: The Origins of the English Novel. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983, 113

- Foley 59

- The Passing Parade – John Doremus – Radio 2CH, 21 June 2007

Further reading

- Psalmanazar, George, A Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, in Japan in Eighteenth-Century English Satirical Writings (5 vols), ed. Takau Shimada, Tokyo: Edition Synapse. ISBN 978-4-86166-034-4

- Collins, Paul, Chapter 7 of Banvard's Folly, Picadore USA, 2001 ISBN 0 330 48688 8

- Keevak, Michael. The Pretended Asian: George Psalmanazar's Eighteenth-Century Formosan Hoax, Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8143-3198-9

- Lynch, Jack, "Forgery as Performance Art: The Strange Case of George Psalmanazar" in 1650–1850: Ideas, Aesthetics, and Inquiries in the Early Modern Era 11, 2005, pp. 21–35

External links

Media related to George Psalmanazar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Psalmanazar at Wikimedia Commons- Works by or about George Psalmanazar at Internet Archive

- Selections from An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa