Geography of the Yosemite area

Yosemite National Park is located in the central Sierra Nevada of California. Three wilderness areas are adjacent to Yosemite: the Ansel Adams Wilderness to the southeast, the Hoover Wilderness to the northeast, and the Emigrant Wilderness to the north.

The 1,189 sq mi (3,080 km2) park is roughly the size of the U.S. state of Rhode Island and contains thousands of lakes and ponds, 1,600 miles (2,600 km) of streams, 800 miles (1,300 km) of hiking trails, and 350 miles (560 km) of roads.[1] Two federally designated Wild and Scenic Rivers, the Merced and the Tuolumne, begin within Yosemite's borders and flow westward through the Sierra foothills, into the Central Valley of California. Annual park visitation exceeds 3.5 million, with most visitor use concentrated in the seven-square-mile (18 km2) area of Yosemite Valley.[1]

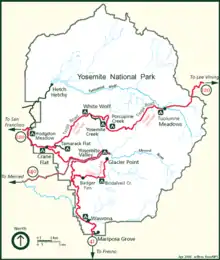

The geography of the Yosemite area can be visualized with the clickable map, below:

Rocks and erosion

Almost all of the landforms in the Yosemite area are cut from the granitic rock of the Sierra Nevada Batholith (a batholith is a large mass of intrusive igneous rock that formed deep below the surface).[2] About 5% of the park's landforms (mostly in its eastern margin near Mount Dana) are metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks.[3] These rocks are called roof pendants because they were once the roof of the underlying granitic rock.[4]

Erosion acting upon different types of uplift-created joint and fracture systems is responsible for creating the valleys, canyons, domes, and other features we see today. These joints and fracture systems do not move, and are therefore not faults.[5] Spacing between joints is controlled by the amount of silica in the granite and granodiorite rocks; more silica tends to create a more resistant rock, resulting in larger spaces between joints and fractures.[6]

Pillars and columns, such as Washington Column and Lost Arrow, are created by cross joints. Erosion acting on master joints is responsible for creating valleys and later canyons.[6] The single most erosive force over the last few million years has been large alpine glaciers, which have turned the previously V-shaped river-cut valleys into U-shaped glacial-cut canyons (such as Yosemite Valley and Hetch Hetchy Valley). Exfoliation (caused by the tendency of crystals in plutonic rocks to expand at the surface) acting on granitic rock with widely spaced joints is responsible for creating domes such as Half Dome and North Dome and inset arches like Royal Arches.[7]

Popular features

Yosemite Valley represents only one percent of the park area, but this is where most visitors arrive and stay. The Tunnel View is the first view of the Valley for many visitors and is extensively photographed. El Capitan, a prominent granite cliff that looms over Yosemite Valley, is one of the most popular rock climbing destinations in the world because of its diverse range of climbing routes in addition to its year-round accessibility. Granite domes such as Sentinel Dome and Half Dome rise 3,000 and 4,800 feet (910 and 1,460 m), respectively, above the valley floor.

The high country of Yosemite contains beautiful areas such as Tuolumne Meadows, Dana Meadows, the Clark Range, the Cathedral Range, and the Kuna Crest. The Sierra crest and the Pacific Crest Trail run through Yosemite, with peaks of red metamorphic rock, such as Mount Dana and Mount Gibbs, and granite peaks, such as Mount Conness. Mount Lyell is the highest point in the park, standing at 13,120 feet (4,000 m). The Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in Yosemite National Park and is one of the few remaining in the Sierra Nevada today.

The park has three groves of ancient giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum) trees; the Mariposa Grove (200 trees), the Tuolumne Grove (25 trees), and the Merced Grove (20 trees).[8] This species grows larger in volume than any other and is one of the tallest and longest-lived.[9]

Water and ice

Tuolumne and Merced River systems originate along the crest of the Sierra Nevada in the park and have carved river canyons 3,000 to 4,000 feet (910 to 1,220 m) deep. The Tuolumne River drains the entire northern portion of the park, an area of approximately 680 square miles (1,800 km2). The Merced River begins in the park's southern peaks, primarily the Cathedral and Clark Ranges, and drains an area of approximately 511 square miles (1,320 km2).[10]

Hydrologic processes, including glaciation, flooding, and fluvial geomorphic response, have been fundamental in creating landforms in the park.[10] The park also contains approximately 3,200 lakes (greater than 100 m2), two reservoirs, and 1,700 miles (2,700 km) of streams, all of which help form these two large watersheds.[11] Wetlands in Yosemite occur in valley bottoms throughout the park, and are often hydrologically linked to nearby lakes and rivers through seasonal flooding and groundwater movement. Meadow habitats, distributed at elevations from 3,000 to 11,000 feet (910 to 3,350 m) in the park, are generally wetlands, as are the riparian habitats found on the banks of Yosemite's numerous streams and rivers.[12]

Yosemite is famous for its high concentration of waterfalls in a small area. Numerous sheer drops, glacial steps and hanging valleys in the park provide many places for waterfalls to exist, especially during April, May, and June (the snowmelt season). Located in Yosemite Valley, the Yosemite Falls is the highest in North America at 2,425-foot (739 m). Also in Yosemite Valley is the much lower volume Ribbon Falls, which has the highest single vertical drop, 1,612 feet (491 m).[9] Perhaps the most prominent of the Yosemite Valley waterfalls is Bridalveil Fall, which is the waterfall seen from the Tunnel View viewpoint at the east end of the Wawona Tunnel. Wapama Falls in Hetch Hetchy Valley is another notable waterfall. Hundreds of ephemeral waterfalls also exist in the park.

All glaciers in the park are relatively small glaciers that occupy areas that are in almost permanent shade, such as north- and northeast-facing cirques. Lyell Glacier is the largest glacier in Yosemite (the Palisades Glaciers are the largest in the Sierra Nevada) and covers 160 acres (65 ha).[13] None of the Yosemite glaciers are a remnant of the much, much larger Ice Age alpine glaciers responsible for sculpting the Yosemite landscape. Instead, they were formed during one of the neoglacial episodes that have occurred since the thawing of the Ice Age (such as the Little Ice Age).[8] Climate change has reduced the number and size of glaciers around the world. Many Yosemite glaciers, including Merced Glacier, which was discovered by John Muir in 1871 and bolstered his glacial origins theory of the Yosemite area, have disappeared and most of the others have lost up to 75% of their surface area.[13]

Climate

Yosemite has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification Csa), meaning most precipitation falls during the mild winter, and the other seasons are nearly dry (less than 3% of precipitation falls during the long, hot summers).[14] Because of orographic lift, precipitation increases with elevation up to 8,000 feet (2,400 m) where it slowly decreases to the crest. Precipitation amounts vary from 36 inches (910 mm) at 4,000 feet (1,200 m) elevation to 50 inches (1,300 mm) at 8,600 feet (2,600 m). Snow does not typically persist on the ground until November in the high country. It accumulates all winter and into March or early April.[15]

Mean daily temperatures range from 25 °F (−4 °C) to 53 °F (12 °C) at Tuolumne Meadows at 8,600 feet (2,600 m). At the Wawona Entrance (elevation 5,130 feet or 1,560 metres), mean daily temperature ranges from 36 to 67 °F (2 to 19 °C). At the lower elevations below 5,000 feet (1,500 m), temperatures are hotter; the mean daily high temperature at Yosemite Valley (elevation 3,966 feet or 1,209 metres) varies from 46 to 90 °F (8 to 32 °C). At elevations above 8,000 feet (2,400 m), the hot, dry summer temperatures are moderated by frequent summer thunderstorms, along with snow that can persist into July. The combination of dry vegetation, low relative humidity, and thunderstorms results in frequent lightning-caused fires as well.[15]

At the park headquarters, with an elevation of 3,966 feet (1,209 m), January averages 38.2 °F (3.4 °C), while July averages 73.0 °F (22.8 °C), though in summer the nights are much cooler than the hot days.[16] There are an average of 39.5 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and an average of 97.9 nights with freezing temperatures.[16] Freezing temperatures have been recorded in every month of the year. The record high temperature was 115 °F (46 °C) on July 20, 1915, while the record low temperature was −6 °F (−21 °C) on January 2, 1924 and on January 21, 1937.[16][17] Average annual precipitation is nearly 37 inches (940 mm), falling on 65 days. The wettest year was 1983 with 68.94 inches (1,751 mm) and the driest year was 1976 with 14.84 inches (377 mm).[17] The most precipitation in one month was 29.61 inches (752 mm) in December 1955 and the most in one day was 6.92 inches (176 mm) on December 23, 1955.[17] Average annual snowfall is 65.6 inches (1.67 m). The snowiest year was 1967 with 154.9 inches (3.93 m). The most snow in one month was 140.8 inches (3.58 m) in January 1993.[17]

| Climate data for Yosemite Park Headquarters, elev. 3,966 feet (1,209 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

82 (28) |

90 (32) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

103 (39) |

115 (46) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

98 (37) |

86 (30) |

73 (23) |

115 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.2 (8.4) |

53.1 (11.7) |

58.7 (14.8) |

65.9 (18.8) |

72.8 (22.7) |

81.4 (27.4) |

89.9 (32.2) |

89.5 (31.9) |

83.5 (28.6) |

73.5 (23.1) |

57.7 (14.3) |

47.5 (8.6) |

68.3 (20.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 25.6 (−3.6) |

28.1 (−2.2) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

35.9 (2.2) |

41.6 (5.3) |

47.3 (8.5) |

53.2 (11.8) |

52.0 (11.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

38.3 (3.5) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

38.0 (3.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −6 (−21) |

1 (−17) |

9 (−13) |

12 (−11) |

15 (−9) |

14 (−10) |

32 (0) |

32 (0) |

24 (−4) |

19 (−7) |

10 (−12) |

−1 (−18) |

−6 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 6.51 (165) |

6.17 (157) |

5.39 (137) |

3.04 (77) |

1.47 (37) |

0.70 (18) |

0.31 (7.9) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.66 (17) |

1.91 (49) |

3.93 (100) |

5.97 (152) |

36.26 (922) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 16.2 (41) |

14.6 (37) |

12.9 (33) |

5.1 (13) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

3.6 (9.1) |

12.5 (32) |

65.6 (167) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9 | 9 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 65 |

| Source: WRCC (1905-2012)[17] | |||||||||||||

Notes

- "Nature & Science". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- Harris 1998, p. 329

- "Geology: The Making of the Landscape". United States National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Geological Survey Professional Paper 160: Geologic History of the Yosemite Valley - The Sierra Block". United States Geological Survey. November 28, 2006. Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- Harris 1998, p. 331

- Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 220

- Harris 1998, p. 332

- Harris 1998, p. 340

- Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 227

- "Water Overview". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Hydrology and Watersheds". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "Wetland Vegetation". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on April 19, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- Kiver & Harris 1999, p. 228

- Wuerthner 1994, p. 8

- "Climate". National Park Service: Yosemite National Park. December 22, 2004. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- "NOWData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- "Yosemite Park HDQTRS, California". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved June 9, 2013.