Gendarme (historical)

A gendarme was a heavy cavalryman of noble birth, primarily serving in the French army from the Late Middle Ages to the Early Modern period. Heirs to the knights of French medieval feudal armies, French Gendarmes also enjoyed a stellar reputation and were regarded as the finest European heavy cavalry force[1] until the decline of chivalric ideals largely due to the ever-evolving developments in gunpowder technology. They provided the Kings of France with a potent regular force of armored lancers which, when properly employed, dominated late medieval and early modern battlefields. Their symbolic demise is generally considered to be the Battle of Pavia, which inversely is seen as confirming the rise of the Spanish Tercios as the new dominant military force in Europe.

.JPG.webp)

Etymology

The word gendarme derives originally from the French homme d'armes (man-at-arms), plural of which is gens d'armes. The plural sense was later shortened to gendarmes and a singular made of this, gendarme.

History

Origin

Like most fifteenth-century sovereigns, the Kings of France sought to possess standing armies of professionals to fight their incessant wars, most notable of which was the Hundred Years War. By that period, the old form of feudal levy had long proven inadequate and had been replaced by various ad hoc methods of paying vassal troops serving for money rather than simply out of feudal obligation, a method that was heavily supplemented by hiring large numbers of out-and-out mercenaries. These methods, though improvements on the old annual 40-day service owed by knights (the traditional warrior elites of Medieval Europe), were also subject to strain over long campaigns. During periods of peace they also resulted in social destabilization, as the mercenary companies—referred to in this period as routiers—refused to disband until granted their back-pay (which was invariably hopelessly in arrears), and generally looted and terrorized the areas they occupied.

The French kings sought a solution to these problems by issuing ordinances (ordonnances) which established standing armies by which units were permanently embodied, based, and organized into formations of set size. Men in these units signed a contract which kept them in the service of the unit for periods of one year or longer. The first such French ordinance was issued by King Charles VII at the general parliament of Orléans in 1439, and was meant to raise a body of troops to crush the devastating incursions of the Armagnacs.

French gendarme companies

Eventually more ordinances would set the general guidelines for the organization of companies of gendarmes, the troops in which were accordingly called the gendarmes d'ordonnance. Each of the 15 gendarme companies was to be of 100 lances fournies, each composed of six mounted men—a noble heavy armoured horseman, a more lightly armed fellow combatant (coutillier), a page (a non-combatant) and three mounted archers meant as infantry support. The archers were intended to ride to battle and dismount to shoot with their bows, and did so until late in the fifteenth century, when they took to fighting on horseback as a sort of lighter variety of gendarme, though still called "Archers." These later archers had armour less heavy than the gendarmes, and a light lance, but could deliver a capable charge when necessary.

This organization was provisional, however, and one of the mounted archers was commonly replaced by another non-combatant, a servant (valet).

In 1434, the pay for the members of the company was set as 120 livres for gendarmes, 60 for coutilliers, 48 for archers, and 36 for the non-combatants.[2]

Gendarme unit organization evolved over time. The retention of the lance as a relevant small unit formation, a relic of medieval times, gradually fell away in the sixteenth century, and, by an edict of 1534, Francis I declared that a company of gendarmes would be made up of 40 gendarme heavy, and sixty archer medium, cavalry (each gendarme having two unarmed attendants, pages and/or valets), thus practically ending the old proportions of troop types based on the number of lances. By the 1550s, advances in firearm technology dictated that a body of 50 light cavalry armed with an arquebus be attached to each gendarme company.[3]

The heavy cavalrymen in these companies were almost invariably men of gentle birth, who would have served as knights in earlier feudal forces. In many ways they still closely resembled knights—wearing a complete suit of plate armour, they fought on horseback, charging with the heavy lance.

A gendarme company was formed by the crown, the king appointing a magnate to raise the company and be its captain, and paying him for its maintenance. In this way, the bonds between the crown and the magnates were maintained, as the king's patronage essentially bought the loyalty of the nobility.[4] Likewise, appointment of individual gentlemen to a gendarme company (a matter of provincial administration) was mostly accomplished by patronage and recommendation, favouring those with the right family connections. Recruits preferred positions in companies stationed in their home province, but did not always obtain them.[5]

The total number of gendarmes in the companies varied over the decades. The high point was roughly 4,000 lances during the latter part of the reign of Louis XI, but the Estates General of 1484 reduced this to 2,200 lances, which number was thereafter, more or less, the peacetime average. This was generally increased by another 1,000 lances in wartime. When conflict ended, the reduction came either in the number of companies, or in the number of lances in the companies (or by a combination of these two methods). Captains dreaded a reduction of their company as a diminution of their prestige and income, and worked hard to prevent this—which companies were reduced usually reflected the influence of the respective captains at court.[6]

The gendarme companies were permanently stationed in towns in the provinces throughout France, subject to be summoned during wartime and concentrated in the Royal armies. Some became closely associated with the towns where they were stationed. If these garrison towns did not have sufficient resources to support the gendarmes present, as was often the case, individuals often found lodging in nearby areas. This lack of lodging could apply even in times of peace, when many of the men retired to their homes instead of remaining in the garrison (particularly in winter), and despite the contemporary system of giving leave, which allowed up to one quarter of the company to be away at any given time. Men who were away for these reasons were to be brought back to the company by the captains when ordered to do so by the provincial governor. Long-term absence was a chronic problem in the companies.[7]

The French ordinances established regular infantry forces as well, but these were substantially less successful.

Burgundian gendarme companies

It was with his increasingly professional army, including its gendarme heavy cavalry, that the French king ultimately defeated the English in the Hundred Years War and then sought to assert his authority over the semi-independent great duchies of France. When the Burgundian duke Charles the Bold wished to establish an army to stand up to this royal French threat, he emulated the French ordonnance army, raising his own force of gendarmes in ordonnance companies starting informally in 1470, officially establishing these by means of an ordonnance issued in 1471, and refining the companies in further ordonnances issued in 1472, 1473 and 1476. These created twelve ordonnance companies, for a total of 1,200 gendarmes.[8]

Like French companies, the Burgundian gendarmes d'ordonnance companies were also composed of 100 lances, and were similarly raised and garrisoned, but were organized differently, being split into four squadrons (escadres), each of four chambres of six lances each. Each Burgundian lance still contained the six mounted men, but also included three purely infantry soldiers—a crossbowman, a handgunner and a pikeman, who in practice fought in their own formations on the battlefield. There was a twenty-fifth lance in the escadre, that of the squadron commander (chef d'escadre).

The newly established Burgundian Ordonnance companies were almost immediately hurled into the cauldron of the Burgundian Wars, where they suffered appalling casualties in a series of disastrous battles with the Swiss, including the loss of the Duke himself, leaving no male heir. Ultimately, however, elements of his gendarmes d'ordonnance were re-established by Philip the Handsome on a smaller scale, and these companies survived to fight in Habsburg forces into the sixteenth century.[9]

Gendarmes in battle in the early sixteenth century

France entered the sixteenth century with its gendarme companies being the largest and most respected force of heavy cavalry in Europe, feared for their powerful armament, reckless courage and esprit de corps.[10] As the fifteenth century waned, so did the tactical practices of the Hundred Years War, and the gendarmes of the sixteenth century returned to fighting exclusively on horseback, generally in a very thin line (en haye), usually two or even just one rank deep, so as to maximize the number of lances being set upon the enemy target at once.

As such, the early to mid sixteenth century may appear to modern viewers to be a period of military anachronism—heavily armoured cavalry, appearing to all the world as the knights of old, careened across the battlefield alongside rapidly modernizing heavy artillery and infantry bearing firearms.

However, the gendarme cavalry, when properly employed, could still be a decisive arm, as they could deliver a potent shock attack and remained fairly maneuverable despite the extremely heavy armour they now wore to defend themselves from increasingly powerful firearms. At some battles, such as at Seminara, Fornovo and Ravenna, they clashed with their heavily armoured opposite numbers, and prevailed, dominating the battle. In others, such as at Marignano, they were part of a de facto combined arms team, operating in conjunction with infantry and artillery to achieve battlefield victory against an all-infantry foe. They could also function, by plan or by chance, as a decisive reserve which could enter into a confused battle and crush disordered enemy infantry. The prime example of this would be at Ravenna, where the gendarmes, having just driven the Spanish cavalry off the field, then reversed the results of the infantry clash in which the Spanish had prevailed, riding down the disordered Spanish foot.

However, when unsupported and facing enemy infantry in good order, particularly those in pike and shot formations or in a strong defensive position, they suffered heavy casualties despite their now immensely thick armour. Examples include the Battle of Pavia, when the French cavalry were shot down by Spanish infantry who sought cover in broken terrain, and at Ceresole, when the French gendarmes sacrificed themselves in fruitless charges against the self-supporting Imperial infantry regiments. The pike and shot formation developed by the Spanish was particularly deadly to the gendarmes, who suffered heavy casualties from arquebus and musket fire, but were unable to overrun the vulnerable shooters due to the protection offered by the pikemen of the formation, though successfully delaying them from intervening in the main center engagement. Also proving effective in the same battle routing the pike and shot formations engaged in the center via a charge into the flank by a group of 80 Gendarmes under the command of Boutières.

Evolution into lighter cavalry in the later Sixteenth Century

Starting in the 1540s another challenge to the gendarmes appear in the form of the German reiter cavalry armed with wheellock pistols, who offered a cheaper form of heavy cavalry to the extremely expensive gendarme. While the effectiveness of these firearms cavalry varied, a number of notable French captains during the French Wars of Religion including Francois de la Noue and Gaspard de Saulx, became heavy critics of the lance and firm advocate of the use of pistols on horseback.

De la Noue in particular wrote in his memoir:

"Whereupon I will say that although the squadrons of the spears [i.e. lances] do give a gallant charge, yet it can work no great effect, for at the outset it killed none, yea it is a miracle if any be slain with the spear. Only it may wound some horse, and as for the shock, it is many times of the small force, where the perfect reiter do never discharge their pistols but in jointing, and striking at hand, they wound, aiming always either at the face or the thigh. The second rank also shoot off so the forefront of the men-or-arms squadron is at the first meeting half overthrown and maimed. Although the first rank may with their spears do some hurt, especially to the horses, yet the other ranks following cannot do so, at leas the second or third, but are driven to cast away their spears and help themselves with their swords. Herein we are to consider two things which experience hath confirmed. The one, that the reiter are never so dangerous as when they be mingled with the enemy, for then be they all fire. The other, the two squadrons meeting, they have scarce discharged the second pistol but either the one or the other turned away. For they contested no longer as the Romans did against other nations, who oftentimes keep the field fighting two hours face to face before either party turned back. By all the afore-said reasons, I am driven to avow that a squadron of pistols, doing their duties, shall break a squadron of spears."[11]

De Saulx noted in his own memoir:

"The large pistols make close action so dangerous that everyone wants to leave, making the fights shorter"[12]

The French, starting with the Huguenot rebels, rapidly replaced the heavy gendarme lance with two pistols, and the armour of the gendarme rapidly lightened to give the horseman more mobility (and to cut the extreme cost of fielding such troops). The tremendous victories won by Henry IV in such battles as Ivry, Arques and Coutras, largely won by his pistolier cavalry against the traditionally-equipped royalist gendarmes, led to the complete conversion of the gendarme into the use of firearms by the end of the 16th century. Such changes were also happening in other Western European nations, with the Dutch under Maurice of Nassau discarding the lance in 1597.

Gendarmes after the sixteenth century

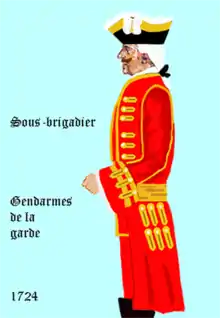

Cavalry called gendarmes continued to serve in French armies for centuries to follow, often with prominence (such as in the wars of Louis XIV), but with less distinctive features than during the sixteenth century. The Royal Guard, known as the Maison militaire du roi de France, had two units of gendarmes : the Gendarmes de la garde (Guard Gendarmes), created in 1609 and the Gendarmes de France or Gendarmes d'Ordonnance, units of regular cavalry continuing the traditions of sixteenth-century Gendarmes.

In 1720, the Maréchaussée de France, a police force under the authority of the marshals of France, was put under the administrative authority of the Gendarmerie de France. The Gendarmerie was dissolved in 1788 and the Maréchaussée in 1791, only to be recreated as a new police force of military status, the gendarmerie Nationale, which still exists. This explains the evolution of the meaning of the word gendarme from a noble man-at-arms to a military police officer.

Under Napoleon I, The Gendarmes d'élite de la Garde impériale (English: "élite gendarmes of the Imperial Guard") was a gendarmerie unit formed in 1801 by Napoleon as part of the Consular Guard which became the Imperial Guard in 1804. In time of peace, their role was to protect official residences and palaces and to provide security to important political figures. In time of war, their role was to protect the Imperial headquarters, to escort prisoners and occasionally to enforce the law and limit civil disorder in conquered cities. The unit was renamed Gendarmes des chasses du roi during the First Bourbon Restoration but was disbanded in 1815 during the Second Restoration.

References and notes

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009-12-23). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 83

- Potter, War and Government, 159

- Carroll, Noble Power, 69

- Potter, 162

- Potter, 159

- Potter, 160-161

- Contamine, War in the Middle Ages, 171

- Contamine, 171

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009-12-23). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

- François de la Noue, The Politick and Military Discourses of the Lord de la Noue, translated by Aggas, London 1587, ppg 201-202

- Saulx, Jean de, vicomte de Tavannes ([c. 1620]; reprinted 1822). Mémoires de très-noble et très-illustre Gaspard de Saulx, seigneur de Tavannes, mareschal de France, admiral des mers de Levant, gouverneur de Provence, conseiller du roy, et capitaine de cent hommes d'armes, reprinted in Collection complèt̀e des méḿoires relatifs à ̀l'histoire de France, edited by M. Petitot. Paris: Foucault. Vols. 23, 24, & 25. OCLC 39499947, ppg 180.

Sources

- Carroll, Stuart. Noble Power During the French Wars of Religion: The Guise Affinity and the Catholic Cause in Normandy, 1998.

- Contamine, Phillipe. War in the Middle Ages, 1980 (reprint edition, 1992).

- Potter, David. War and Government in the French Provinces, 2002

Further reading

- Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War, 1920 (reprint edition, 1990), trans. Walter, J. Renfroe.

- Volume 3: Medieval Warfare

- Volume 4: The Dawn of Modern Warfare.

- Elting, John Robert. Swords Around a Throne: Napoleon's Grande Armée, 1997.

- Oman, Sir Charles, A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century, 1937.

- Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, volume 18 (1939), page 83.

- Oman, Sir Charles, A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages, rev. ed. 1960.

- Taylor, Frederick Lewis. The Art of War in Italy, 1494-1529, 1921.

- Wood, James B. The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-76, 1996.