Gaspar da Cruz

Gaspar da Cruz (c. 1520 – 5 February 1570; sometimes also known under an Hispanized version of his name, Gaspar de la Cruz[1]) was a Portuguese Dominican friar born in Évora, who traveled to Asia and wrote one of the first detailed European accounts about China.

Gaspar da Cruz | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1520 |

| Died | 5 February 1570 (aged 49–50) |

| Occupation | Dominican friar, writer |

Biography

Gaspar da Cruz was admitted to the Order of Preachers (Dominican order) convent of Azeitão. In 1548, along with 10 other friars.[2] Gaspar da Cruz embarked for Portuguese India under the orders of Friar Diogo Bermudes, with the purpose of founding a Dominican mission in the East. For six years, Cruz remained in Hindustan, probably in Goa, Chaul and Kochi, as his Order had established a settlement there. During this time he also visited Portuguese Ceylon.

In 1554, Cruz was in Malacca, where he founded a house under his Order, living there until September 1555. He was then shipped to Cambodia. Given the failure of the Cambodian mission,[3] in late 1556 Cruz went to Lampacao, a small island in the Guangzhou bay, six leagues north of Shangchuan Island (Sanchão). At that time, Lamapacao island was a port for trade with the Chinese. At Lampacao, he was able to obtain a permission to go to Guangzhou, and spent a month preaching there.[1]

In 1557, Cruz returned to Malacca.

In 1560, Cruz headed to Hormuz where he gave support to soldiers of the Portuguese fort. He probably returned to India about 3 years later, although there are no definite records for this period. It is likely that Cruz returned to Portugal in 1565, returning to Lisbon in 1569, where he was documented helping victims of the plague. He later returned to his convent in Setúbal where he died of the plague on February 5, 1570.

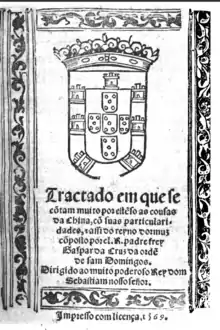

A Treatise of China

Cruz's book, Tratado das cousas da China (Treatise on things Chinese) was published by André de Burgos, of Évora, in 1569. The full title, in the original orthography, was Tractado em que se cõtam muito por estẽso as cousas da China. It is often described as the first European book whose main topic was China;[4][5] at any rate, it is one of the first undisputed books on China published in Europe since that of Marco Polo.

The book also contains accounts of Cambodia and Hormuz.

Influence

In Donald F. Lach's assessment, Cruz' book itself did not become widely distributed in Europe either because it was published in Portuguese (rather than some more widely spoken language), or because it appeared in the year of the plague.[4] Nonetheless, Cruz' book, at least indirectly, played a key role in forming the European view of China in the sixteenth century, alongside the earlier and shorter account by Galeote Pereira (1565).[6] Cruz' Treatise (along with João de Barros' earlier coverage of China in his Decadas) was the main source of information for Bernardino de Escalante's Discourso ... de las grandezas del Reino de la China (1577), and one of the main sources for the much more famous and widely translated History of the great and mighty kingdom of China compiled by Juan González de Mendoza in 1585.[4]

While Escalante's and Mendoza's works were translated into many European languages within a few years after the appearance of the Spanish original (the English versions were published in 1579 and 1588, respectively), Cruz' text only appeared in English in 1625, in Samuel Purchas' Purchas his Pilgrimes, and even then only in an abridged form, as A Treatise of China and the adjoining regions, written by Gaspar da Cruz a Dominican Friar, and dedicated to Sebastian, King of Portugal: here abbreviated.[7] By this time his report had been superseded not only by Mendoza's celebrated treatise, but also by the much more informed work of Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault, De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas (Latin 1616; English abridgment, in the same Purchas' collection of 1625).

Chinese language and writing

Reading Gaspar da Cruz' Treatise, one has an impression that, as of 1555, communication between the Portuguese and the Chinese was accomplished primarily thanks to the existence of some Chinese people able to speak Portuguese, rather than the other way around. His book several times mentions Chinese interpreters working with Portuguese, but never a Portuguese person speaking or reading Chinese. (This was not any different from the situation that obtained in the accounts of da Cruz' Spanish colleague Martín de Rada's expedition to Fujian in 1575). The Portuguese, of course, did know some Chinese words and common expressions: da Cruz' book contains, for example, titles of various officials, or the word cha ("tea").

Da Cruz was, however, curious about the Chinese writing system, and gave a brief report of it, which John DeFrancis has described as "the first Western account of the fascinatingly different Chinese writing."[8]

Slavery

One of the major irritants in the early Sino-Portuguese relations was the Portuguese' proclivity to enslave Chinese children and take them to various Portuguese colonies, or to Portugal itself. While this traffic was on a much smaller scale than the Atlantic slave trade, supplying millions of African slaves for Portuguese Brazil, it was a contributing factor already to the failure of the Tomé Pires' 1521 embassy, when, in a words of a later researcher, many residents of Canton discovered that "many of their children, whom they had given in pledge to their creditors, had been kidnapped by" Simão de Andrade "and carried away to become slaves".[9] Gaspar da Cruz was aware of this trade, and, as his book (Chapter XV) implies, he had heard of the Portuguese slavers' attempts to justify their actions by claiming that they had been merely buying children that already were slaves while in China. Da Cruz described the situation with slavery in China as he saw it. According to him, the laws of China allowed impoverished widows to sell her children; however, the conditions under which boys or girls sold into servitude could be kept were regulated by law and custom, and upon reaching a certain age they had to be set free. Reselling of such slaves (or, rather, bond-servants) was regulated too, there being "great penalties" for selling any of them to the Portuguese. He concludes therefore (as C.R. Boxer summarizes his argument), that "the Portuguese had no legal or moral rights to purchase either mui-tsai or kidnapped children for use as slaves":

Now let each one who reads this judge, if some Chinas should sell to some Portugals one of these slaves, whether such a slave would be lawfully acquired, - how much more when none of them are sold. And all those who commonly are sold to the Portugals are stolen, and so they carry them deceived and secretly to the Portugals, and so they sell them. If they were perceived or taken in these stealths, they would be condemned to death. And if it should happen that some Portugal might say that he bought his China slave in China with the permission of some justice, even this would not give him lawful authority to own him. Because such an officer would have done what he did for the sake of the bribe...[10]

God's punishment for sins

In the first paragraph of the last chapter (XXIX) of his book Cruz severely criticized "a filthy abomination, which is that they are so given to the accursed sin of unnatural vice, which is in no way reproved among them."[11] The rest of the chapter, entitled "Of some punishments from God which the Chinas received in the year of fifty-six", discusses the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake and certain flooding events of the same year, which da Cruz views as God's punishment for "this sin".[12]

See also

- Tomé Pires, an unsuccessful Portuguese envoy to the Ming Court ca. 1518-1521

- Martín de Rada, a Spanish Augustinian friar to visit China in 1575; Juan González de Mendoza's book gives an account of de Rada's and other Spanish expeditions

References

- Borao 2009, pp. 1–2

- "The Portuguese empire, 1415–1808: a world on the move", p. 92, A. J. R. Russell-Wood

- Lach 1965, p. 565

- "The first European book devoted exclusively to China", in Lach 1965, pp. 742–743

- "The first European to have published a book on Ming China", in: Title Asian travel in the Renaissance. Volume 17, Issue 3 of Renaissance studies. Wiley-Blackwell. 2004.

- "First globalization: the Eurasian exchange, 1500 to 1800", p.200, Geoffrey C. Gunn

- Boxer et al. 1953, p. vii

- DeFrancis, John (1984), The Chinese language: fact and fantasy, University of Hawaii Press, p. 133, ISBN 0-8248-1068-6

- Donald Ferguson, ed. (1902). Letters from Portuguese captives in Canton, written in 1534 & 1536: with an introduction on Portuguese intercourse with China in the first half of the sixteenth century. Educ. Steam Press, Byculla. pp. 14–15.. According to Cortesão's later research, the letters were actually written in 1524.

- Boxer et al. 1953, pp. 149–152

- Hinsch, Bret. (1990). Passions of the Cut Sleeve. Published by University of California Press. p. 2

- Boxer et al. 1953, pp. 223–227

Bibliography

- Cruz, Gaspar da (1569), Tractado em que se cõtam muito por estẽso as cousas da China, cõ suas particularidades, e assi do reyno dormuz., em casa de Andre de Burgos (The original 1569 edition of da Cruz' book, in black letter, digitized by Google)

- Cruz, Gaspar da (1937), Tractado em que se contam muito por extenso as cousas da China, com suas particularidades, e assi do Reyno de Ormuz: com uma nótula bio-bibliográfica, Portucalense Editora (Modern reprint; snippet view only on Google Books)

- Boxer, Charles Ralph; Pereira, Galeote; Cruz, Gaspar da; Rada, Martín de (1953), South China in the sixteenth century: being the narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O.P. (and) Fr. Martín de Rada, O.E.S.A. (1550-1575), Issue 106 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, Printed for the Hakluyt Society (Includes an English translation of Gaspar da Cruz's entire book, with C.R. Boxer's comments)

- A Treatise of China and the adjoyning Regions, written by Gaspar da Cruz a Dominican Friar, and dedicated to Sebastian King of Portugal: here abbreviated, in: Hakluytus posthumus, or, Purchas his Pilgrimes: contayning a history of the world in sea voyages and lande travells by Englishmen and others, v.11 : Purchas, Samuel, 1577?-1626]. (The same early translation of da Cruz' work, starting at page 474)

- Lach, Donald F. (1965), Asia in the making of Europe, Volume I, Book Two, The University of Chicago Press

- Borao, José Eugenio (2009), "Macao as the non-entry point to China: The case of the Spanish Dominican missionaries (1587-1632)", International Conference on The Role and Status of Macao in the Propagation of Catholicism in the East, Macao, 3-5 November 2009, Centre of Sino-Western Cultural Studies, Istituto Politecnico de Macao. (PDF)