Fusee (horology)

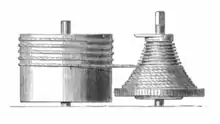

Used in antique spring-powered mechanical watches and clocks, a fusee (from the French fusée, wire wound around a spindle) is a cone-shaped pulley with a helical groove around it, wound with a cord or chain which is attached to the mainspring barrel. Fusees were used from the 15th century to the early 20th century to improve timekeeping by equalizing the uneven pull of the mainspring as it ran down. Gawaine Baillie stated of the fusee, "Perhaps no problem in mechanics has ever been solved so simply and so perfectly."[1]

History

The origin of the fusee is not known. Many sources erroneously credit clockmaker Jacob Zech of Prague with inventing it around 1525,[2][3][4] The earliest definitely dated fusee clock was made by Zech in 1525, but the fusee actually appeared earlier, with the first spring driven clocks in the 15th century.[1][5] The idea probably did not originate with clockmakers, since the earliest known example is in a crossbow windlass shown in a 1405 military manuscript.[1] Drawings from the 15th century by Filippo Brunelleschi[6] and Leonardo da Vinci[7] show fusees. The earliest existing clock with a fusee, also the earliest spring-powered clock, is the Burgunderuhr (Burgundy clock), a chamber clock whose iconography suggests that it was made for Phillipe the Good, Duke of Burgundy about 1430, now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum[1][5] The word fusee comes from the French fusée and late Latin fusata, 'spindle full of thread'.

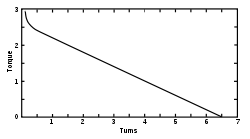

Springs were first employed to power clocks in the 15th century, to make them smaller and portable.[1][5] These early spring-driven clocks were much less accurate than weight-driven clocks. Unlike a weight on a cord, which exerts a constant force to turn the clock's wheels, the force a spring exerts diminishes as the spring unwinds. The primitive verge and foliot timekeeping mechanism, used in all early clocks, was sensitive to changes in drive force. So early spring-driven clocks slowed down over their running period as the mainspring unwound, causing inaccurate timekeeping. This problem is called lack of isochronism.

Two solutions to this problem appeared with the first spring driven clocks; the stackfreed and the fusee.[1] The stackfreed, a crude cam compensator, added a lot of friction and was abandoned after less than a century.[8] The fusee was a much more lasting idea. As the movement ran, the tapering shape of the fusee pulley continuously changed the mechanical advantage of the pull from the mainspring, compensating for the diminishing spring force. Clockmakers apparently empirically discovered the correct shape for the fusee, which is not a simple cone but a hyperboloid.[9] The first fusees were long and slender, but later ones have a more squat compact shape. Fusees became the standard method of getting constant force from a mainspring, used in most spring-wound clocks, and watches when they appeared in the 17th century.

At first the fusee cord was made of gut, or sometimes wire. Around 1650 chains began to be used, which lasted longer.[6] Gruet of Geneva is widely credited with introducing them in 1664,[2] although the first reference to a fusee chain is around 1540.[6] Fusees designed for use with cords can be distinguished by their grooves, which have a circular cross section, where ones designed for chains have rectangular-shaped grooves.

Around 1726 John Harrison added the maintaining power spring to the fusee to keep marine chronometers running during winding, and this was generally adopted.

How it works

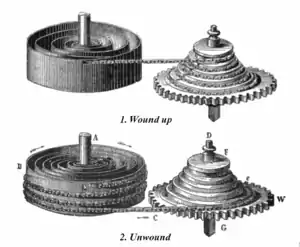

The mainspring is coiled around a stationary axle (arbor), inside a cylindrical box, the barrel. The force of the spring turns the barrel. In a fusee clock, the barrel turns the fusee by pulling on the chain, and the fusee turns the clock's gears.

- When the mainspring is wound up (Fig. 1), all the chain is wrapped around the fusee from bottom to top, and the end going to the barrel comes off the narrow top end of the fusee. So the strong pull of the wound up mainspring is applied to the small end of the fusee, and the torque on the fusee is reduced by the small lever arm of the fusee radius.

- As the clock runs, the chain is unwound from the fusee from top to bottom and wound on the barrel.

- As the mainspring runs down (Fig. 2), more of the chain is wrapped on the barrel, and the chain going to the barrel comes off the wide bottom grooves of the fusee. Now the weaker pull of the mainspring is applied to the larger radius of the bottom of the fusee. The greater turning moment provided by the larger radius at the fusee compensates for the weaker force of the spring, keeping the drive torque constant.

- To wind the clock up again, a key is fitted to the protruding squared off axle (winding arbor) of the fusee and the fusee is turned. The pull of the fusee unwinds the chain off the barrel and back onto the fusee, turning the barrel and winding the mainspring. The presence of the fusee means that the force required to wind up the mainspring is constant; it does not increase as the mainspring tightens.

The gear on the fusee drives the movement's wheel train, usually the center wheel. There is a ratchet between the fusee and its gear (not visible, inside the fusee) which prevents the fusee from turning the clock's wheel train backwards while it is being wound up. In quality watches and many later fusee movements there is also a maintaining power spring, to provide temporary force to keep the movement going while it is being wound. This type is called a going fusee. It is usually a planetary gear mechanism (epicyclic gearing) in the base of the fusee "cone") which then provides turning power in the opposite direction to the 'winding up' direction therefore keeping the watch or clock running during winding.

Most fusee clocks and watches include a 'winding stop' mechanism to prevent the mainspring and fusee from being wound up too far, possibly breaking the chain. As it is wound, the fusee chain rises toward the top of the fusee. When it reaches the top, it presses against a lever, which moves a metal blade into the path of a projection sticking out from the edge of the fusee. As the fusee turns, the projection catches on the blade, preventing further winding.[11]

The normal fusee can only be wound in one direction. Drunken fusees were developed, but rarely used, to allow the fusee to be wound in either direction.[12] John Arnold unsuccessfully used them in a few marine chronometers.[13]

Obsolescence

The fusee was a good mainspring compensator, but it was also expensive, difficult to adjust, and had other disadvantages:

- It was bulky and tall, and made pocket watches unfashionably thick.[14]

- If the mainspring broke and had to be replaced, a frequent occurrence with early mainsprings, the fusee had to be readjusted to the new spring.

- If the fusee chain broke, the force of the mainspring sent the end whipping about the inside of the clock, causing damage.

Achieving isochrony was recognised as a serious problem throughout the 500-year history of spring-driven clocks. Many parts were gradually improved to increase isochronism, and eventually the fusee became unnecessary in most timepieces.

The invention of the pendulum and the balance spring in the mid-17th century made clocks and watches much more isochronous, by making the timekeeping element a harmonic oscillator, with a natural "beat" resistant to change. The pendulum clock with an anchor escapement, invented in 1670, was sufficiently independent of drive force so that only a few had fusees.[15]

In pocketwatches, the verge escapement, which required a fusee, was gradually replaced by escapements which were less sensitive to changes in mainspring force: the cylinder and later the lever escapement. In 1760, Jean-Antoine Lépine dispensed with the fusee, inventing a going barrel to power the watch gear train directly. This contained a very long mainspring, of which only a few turns were used to power the watch. Accordingly, only a part of the mainspring's 'torque curve' was used, where the torque was approximately constant. In the 1780s, pursuing thinner watches, French watchmakers adopted the going barrel with the cylinder escapement. By 1850, the Swiss and American watchmaking industries employed the going barrel exclusively, aided by new methods of adjusting the balance spring so that it was isochronous. England continued to make the bulkier full plate fusee watches until about 1900.[16] They were inexpensive models sold to the lower classes and were derisively called "turnips". After this, the only remaining use for the fusee was in marine chronometers, where the highest precision was needed, and bulk was less of a disadvantage, until they became obsolete in the 1970s.

References

- Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1997). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-15510-2., p. 121

- Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-7808-0008-7.

- White, Lynn Jr. (1966). Medieval Technology and Social Change. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-500266-0., p. 127-128

- Glasgow, David (1885). Watch and Clock Making. London: Cassel & Co. p. 63., p. 63-69

Notes

- White, Lynn Jr. (1966). Medieval Technology and Social Change. New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-500266-0., p.127-128

- Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. p. 126. ISBN 0-7808-0008-7.

- "Clock". Encyclopedia Americana. 28. Grolier. 2000. p. 429. ISBN 0717201120.

- Crombie, Alistair (1995). The History of Science from Augustine to Galileo. Dover. ISBN 0-486-28850-1., p.250

- Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1997). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-15510-2., p.121

- Thompson, David (2006). "Chronology of Clocks". Anthony Gray Clocks. Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-10-10., author is Curator of Horology at the British Museum

- Derry, T.K.; Williams, Trevor (1993). A Short History of Technology: From The Earliest Times To 1900. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-27472-1., p.227

- Milham 1945, p.230

- Burnett, D. Graham (2005). Descartes and the Hyperbolic Quest: Lens making machines and their significance to the 17th century. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 0-87169-953-2., p.29

- This drawing has a slight mechanical inaccuracy. In the mainspring barrel, more turns of the mainspring around the arbor are shown in the bottom drawing than in the top, indicating that the mainspring is in the wound-up state in the bottom drawing, while in actuality the barrel is in the wound-up state in the top drawing, when all the fusee chain is on the fusee, and unwound in the bottom drawing.

- Glasgow, David (1885). Watch and Clock Making. London: Cassel. p. 63., p.63-69

- Watkins, Richard (2018). The Art of Being Drunk. p. 20.

- Watkins, Richard (2016). The Origins of Self-Winding Watches. p. 404.

- Thomson, Adam (1842). Time and Timekeepers. London: Boone. p. 143., p.143

- Milham 1945, p.441

- Oliver Mundy, Glossary, The Watch Cabinet

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Kover, London - 18th Century Watchmaker Blog to discover Kover pocket watches that still exist and documents that refer to the watchmaker