Frumentarii

Frumentarii (also known as vulpes) were officials of the Roman Empire, originally collectors of wheat (frumentum), who also acted as the secret service of the Roman Empire in the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Military of ancient Rome |

|---|

|

|

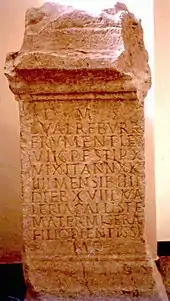

There are two main sources of information about the frumentarii, inscriptions on gravestones and anecdotes where the actions of individual frumentarii are mentioned by historians. From what is known of the Frumentarii, they always worked in uniform. The Empire was based on patronage, not on ideology (until Theodosius I). From inscriptions, one of the few things known about the frumentarii is that they were mostly attached to individual legions, except for a few centurion frumentarii. Attachment to individual legions suggests that their main function was, as the name suggests, to service those legions with supplies.

Frumentarii appear to have spent a lot of time travelling and had a base in Rome at the Castra Peregrina. Frumentarii were obviously proud of their status if they put the rank on their gravestones. There are a number of inscriptions honouring the genie of the Castra Peregrina, this suggests that the frumentarii had high moral and social status.[1]

History

It had been long-standing policy of the Roman legions and armies of occupation to utilize informers and spies, but never in an organized fashion. This was especially true in the city of Rome which was rife with whispers and endless conspiracies. There are two inscriptions of "frumentario canaliculario" found at Arles and Córdoba[2] which suggest that some frumentarii had special knowledge of inland navigation. For all armies, the most important unit of military intelligence was an enemy's geographical location. This included mapped land and communication routes, enemy legion sizes, landmarks, and strategic objectives such as granaries or farms. The Antonine Itinerary might be the product of the frumentarii. Titus used special messengers and assassins of the Praetorian Guard to carry out executions and liquidations (the Speculatores); however, they belonged to the Guard and were limited in scope and power. Rome's Frumentarii were special to Caesar in a sense to that they were his personal servants.

By the 2nd century, the need for an empire-wide intelligence service was clear. But even an emperor could not easily create a new bureau with the express purpose of spying on the citizens of Rome's far-flung domains. A suitable compromise was found by Hadrian. He envisioned a large-scale operation and turned to the frumentarii. The frumentarius was the collector of wheat in a province, a position that brought the official into contact with enough locals and natives to acquire considerable intelligence about any given territory. Hadrian put them to use as his spies, and thus had a ready-made service and a large body to act as a courier system.

The following story has been used as evidence of the role of the frumentarii:

(Hadrian's) vigilance was not confined to his own household but extended to those of his friends, and by means of his private agents (frumentarios) he even pried into all their secrets, and so skilfully that they were never aware that the Emperor was acquainted with their private lives until he revealed it himself. In this connection, the insertion of an incident will not be unwelcome, showing that he found out much about his friends. The wife of a certain man wrote to her husband, complaining that he was so preoccupied by pleasures and baths that he would not return home to her, and Hadrian found this out through his private agents. And so, when the husband asked for a furlough, Hadrian reproached him with his fondness for his baths and his pleasures. Whereupon the man exclaimed: "What, did my wife write you just what she wrote to me?".[3]

References

- P.Faure 2003-1 Les Centurions Frumentaires et le Commandment des Castra Peregrina; 377-427 Mélanges de l'École française de Rome Antiquité, vol 115

- AE 1910,0077 & AE 2003,0931

- chapter 11 in

- Keppie, Lawrence, The Making of the Roman Army from Republic to Empire, Barnes and Noble Books, New York, 1994, ISBN 1-56619-359-1