French expedition to Korea

The French expedition to Korea was an 1866 punitive expedition undertaken by the Second French Empire in retaliation for the earlier Korean execution of seven French Catholic missionaries. The encounter over Ganghwa Island lasted nearly six weeks. The result was an eventual French retreat, and a check on French influence in the region.[5] The encounter also confirmed Korea in its isolationism for another decade, until Japan forced it to open up to trade in 1876 through the Treaty of Ganghwa.

| French expedition to Korea 병인양요/丙寅洋擾 (The Byeong-in yangyo) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown |

600[2] 1 frigate 2 corvettes 2 gunboats 2 dispatch boats | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5 killed (3 at Munsu Fort) 2 wounded (at Munsu Fort) 2 missing[3] |

3 killed 35 wounded[4] | ||||||

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 병인양요 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Byeong-in yangyo |

| McCune–Reischauer | Pyŏng‘in yangyo |

In contemporary South Korea it is known as the Byeong-in yangyo, or "Western disturbance of the byeong-in year".

Background

Throughout the history of the Joseon dynasty, Korea maintained a policy of strict isolationism from the outside world (with the exceptions being interaction with the Qing dynasty and occasional trading with Japan through the island of Tsushima). However, it did not succeed entirely in sealing itself off from foreign contact. Catholic missionaries had begun to show an interest in Korea as early as the 16th century with their arrival in China and Japan.

Through Korean envoy missions to the Qing court in the 18th century, foreign ideas, including Christianity, began to enter Korea and by the late 18th century Korea had its first native Christians. However, it was only in the mid 19th century that the first western Catholic missionaries began to enter Korea. This was done by stealth, either via the China–North Korea border or the Yellow Sea. These French missionaries of the Paris Foreign Missions Society arrived in Korea in the 1840s to proselytize to a growing Korean flock. Bishop Siméon-François Berneux, appointed in 1856 as head of the infant Korean Catholic church, estimated in 1859 that the number of Korean faithful had reached nearly 17,000.[6]

At first, the Korean court turned a blind eye to such incursions. This attitude changed abruptly, however, with the enthronement of the eleven-year-old King Gojong in 1864. By Korean tradition, the regency in the case of a minority would go to the ranking dowager queen. In this case, it was the conservative mother of the previous crown prince, who had died before he could ascend the throne. The new king’s father, Yi Ha-ung, a wily and ambitious man in his early forties, was given the traditional title of the unreigning father of a king: Heungseon Daewongun, or "Prince of the Great Court".

Though the Heungseon Daewongun’s authority at court was not official, stemming in fact from the traditional imperative in Confucian societies for sons to obey their fathers, he quickly seized the initiative and began to control state policy. He was arguably one of the most effective and forceful leaders of the 500-year-old Joseon Dynasty. With the aged dowager regent’s blessing, the Heungseon Daewongun set out upon a dual campaign of both strengthening central authority and isolation from the disintegrating traditional order outside its borders. By the time the Heungseon Daewongun assumed de facto control of the government in 1864, there were twelve French Jesuit priests living and preaching in Korea, and an estimated 23,000 native Korean converts.[8]

In January 1866, Russian ships appeared on the east coast of Korea demanding trading and residency rights in what seemed an echo of the demands made on China by other western powers. Korean Christians with connections at court saw in this an opportunity to advance their cause and suggested an alliance between France and Korea to repel the Russian advances, suggesting further that this alliance could be negotiated through Bishop Berneux. The Heungseon Daewongun seemed open to this idea, but it was possibly a ruse to bring the head of the Korean Catholic Church out into the open; upon Berneux's arrival to the capital in February 1866, he was seized and executed. A round-up then began of the other French Catholic priests and Korean converts.

Several factors contributed to the Heungseon Daewongun‘s decision to crack down on the Catholics. Perhaps the most obvious was the lesson provided by China, that it had apparently reaped nothing but hardship and humiliation from its dealing with the western powers – seen most recently in its disastrous defeat during the Second Opium War. No doubt also fresh in the Heungseon Daewongun‘s mind was the example of the Taiping Rebellion in China, which had been infused with Christian doctrines. 1865 had seen poor harvests in Korea as well as social unrest, which may have contributed to a heightened sensitivity to the foreign creed. The crackdown may also have been related to attempts to combat factional cliques at court, where Christianity had made some inroads.

As a result of the Korean dragnet, all but three of the French missionaries were captured and executed: among them included Bishop Siméon Berneux, as well as Bishop Antoine Daveluy, Father Just de Bretenières, Father Louis Beaulieu, Father Pierre-Henri Dorie, Father Pierre Aumaître, Father Martin-Luc Huin – all of whom were members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, and were canonized by Pope John Paul II on 6 May 1984. An untold number of Korean Catholics also met their end (estimations run around 10,000),[9] many being executed at a place called Jeoldu-san in Seoul on the banks of the Han River.

In late June 1866, one of the three surviving French missionaries, Father Félix-Claire Ridel, managed to escape via a fishing vessel, thanks to 11 Korean converts, and made his way to Chefoo (today known as Yantai), China in early July 1866.[10] Fortuitously in Tianjin at the time of Ridel‘s arrival was the commander of the French Far Eastern Squadron, Rear Admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze. Hearing of the massacre and the affront to French national honor, Roze became determined to launch a punitive expedition against Korea. In this, he was strongly supported by the acting French consul in Peking, Henri de Bellonet.[11]

On the French side, there were several compelling reasons behind the decision to launch a punitive expedition. These had to do with the increasing violence against Christian missionaries and converts within the Chinese interior, which after the Second Opium War in 1860 had been opened up to westerners. The massacre of westerners and Christians in Korea was seen within the context of anti-Western behavior in China by diplomatic and military authorities in the west. Many believed a firm response to such acts of violence was necessary to maintain national prestige and authority.

In response to the event, the French chargé d'affaires in Beijing, Henri de Bellonet, took a number of initiatives without consulting Quai d'Orsay. Bellonet sent a note to the Zongli Yamen threatening to occupy Korea,[12] and he also gave the French Naval Commander in the Far East, rear admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze instructions to launch a punitive expedition against Korea, to which Roze responded: "Since [the kingdom of] Choson killed nine French priests, we shall avenge by killing 9,000 Koreans."[13]

Preliminaries (10 September – 3 October 1866)

Though the French diplomatic and naval authorities in China were eager to launch an expedition, they were stymied by the almost total absence of any detailed information on Korea, including any navigational charts. Prior to the actual expedition, Rear Admiral Roze decided to undertake a smaller surveying expedition along the Korean coast,[14] especially along the waterway leading to the Korean capital of Seoul. This was done in late September and early October 1866. These preliminaries resulted in some rudimentary navigational charts of the waters around Ganghwa Island and the Han River leading to Seoul. The treacherous nature of these waters, however, also convinced Roze that any movement against the fortified Korean capital with his limited numbers and large-hulled vessels was impossible. Instead, he opted to seize and occupy Ganghwa Island, which commanded the entrance to the Han River, in the hopes of blockading the waterway to the capital during the important harvest season and thus forcing demands and reparations on the Korean court.

The nature that these demands were to take was never fully determined. In Peking, the French consul Bellonet had made outrageous (and as it turned out unofficial) demands that the Korean monarch forfeit his crown and cede sovereignty to France.[15] Such a stance was not in keeping with the more circumspect goals of Rear Admiral Roze, who hoped to force reparations. In any case, the demands of Bellonet were never officially endorsed by the French government of Napoleon III. Bellonet would later be severely reprimanded for his importunate blusterings.

Expedition (11 October–12 November 1866)

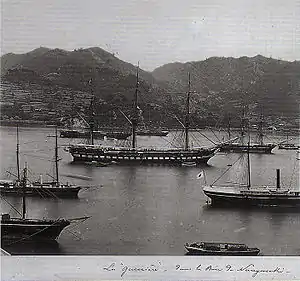

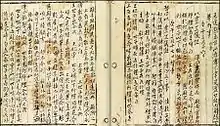

On 11 October, Admiral Roze left Chefoo with one frigate (Guerrière), two avisos (Kien–Chan and Déroulède), two gunboats (Le Brethon and Tardif) and two corvettes (Laplace and Primauguet), as well as almost 300 Naval Fusiliers from their post in Yokohama, Japan. The total number of French troops is estimated at 800.[16] On 16 October, a group of 170 Naval Fusiliers landed on Ganghwa island, seized the fortress which controlled the Han river, and occupied the fortified city of Ganghwa itself. On Ganghwa Island, the Naval Fusiliers managed to seize several fortified positions, as well as booty such as flags, cannons, 8,000 muskets, 23 boxes of silver ingots, a few boxes of gold, and various lacquer works, jades, and manuscripts and paintings that comprised the royal library (Oikyujanggak) on the island.[17]

From his earlier exploratory expedition, Roze knew it was impossible for him to lead a fleet of limited force up the treacherous and shallow Han River to the Korean capital and satisfied himself instead with a "coup de main" on the coast.[18] On the mainland across the narrow channel from Ganghwa Island, however, the French offensive was met with stiff resistance from the troops of General Yi Yong-Hui, to whom Roze sent several letters asking for reparation, without success. A major blow to the French expedition came on 26 October, when 120 French Naval Fusiliers landed briefly on the Korean mainland in an attempt to seize a small fortification at Munsusansong, or Mt. Munsu Fort (depicted in the illustration above). As the landing party came ashore they were met by brisk fire from its Korean defenders.

If the monastery of Munsusansong fell into French hands, the way to Seoul would be open, so, on 7 November, a second landing party was launched by Roze. 160 Naval Fusiliers attacked Munsusansong defended by 543 Korean "Tiger Hunters". Three French soldiers were killed and 36 injured before a retreat was called.[19] Except for continued bombing and surveying activity around Ganghwa and the mouth of the Han River, French forces now largely fortified themselves in and around the city of Ganghwa.

Roze then sent a new letter, asking for the release of the two remaining French missionaries whom he had reason to believe were imprisoned. No answer was forthcoming, but it became clear from activity seen on the mainland across the narrow straits that Korean forces were mobilizing daily. On 9 November, the French were again checked when they attempted to seize a fortified monastery on the southern coast of Ganghwa called Jeongdeung–sa. Here again stiff Korean resistance, coupled by the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Korean defenders, now numbering 10 000 men,[20] forced a French retreat with dozens of casualties but no deaths.

Soon thereafter, with winter approaching and the Korean forces growing stronger, Roze made the strategic decision to evacuate. Before doing so, orders were given to bombard the government buildings on Ganghwa Island and to carry off the varied contents of official storehouses there. It was also learned around this time that the two missing missionaries feared captured in Korea had in fact managed to escape to China. This news contributed to the decision to leave.

All told the French suffered three dead and approximately 35 wounded.[21] In retreating from Korea, Roze attempted to lessen the extent of his retreat by stating that with his limited means, there was little more he could have accomplished, but that his actions would have a dissuasive effect upon the Korean government:

- "The expedition I just accomplished, however modest as it is, may have prepared the ground for a more serious one if deemed necessary, ... The expedition deeply shocked the Korean Nation, by showing her claimed invulnerability was but an illusion. Lastly, the destruction of one of the avenues of Seoul, and the considerable losses suffered by the Korean government should render it more cautious in the future. The objective I had fixed to myself is thus fully accomplished, and the murder of our missionaries has been avenged." report of 15 November by Admiral Roze[22]

The European residents in China considered the results of the expedition minimal and demanded unsuccessfully a larger expedition for the following spring.

After this expedition, Roze with most his fleet returned to Japan, where they were able to welcome the first French military mission to Japan (1867–1868) in the harbour of Yokohama on 13 January 1867. The French government ordered the military to leave as a result of heavy losses in the French intervention in Mexico.

Seized Korean royal books

The books seized by the French at Ganghwa, some 297 volumes of Uigwe, royal court protocols of Korea's last ruling monarchy, the Joseon dynasty, dating from between the 14th and 19th centuries, went on to become the core of the Korea collection in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[23] In 2010 it was revealed that the French government was planning to return the books on a renewable lease to Korea, despite the fact that French law generally prohibited the cession of museum property.[24][25] In early 2011 South Korean president Lee Myung-bak and French president Nicolas Sarkozy finalized an agreement for the return of all the books on a renewable lease. In June 2011 celebrations were held in the port city of Incheon to commemorate their final return. The collection is now being stored in the National Museum of Korea.[26]

Legacy

In the course of these events, in August 1866, a U.S. ship, USS General Sherman foundered on the coast of Korea. Some of the sailors were massacred in retaliation for kidnapping a Korean official, but the United States could not obtain reparations. The United States offered France a combined operation, but the project was abandoned due to the relatively low interest for Korea at that time. An intervention happened in 1871, with the United States Korean expedition.

The Korean government would finally agree to open the country in 1876, when a fleet of the Japanese navy was sent under the orders of Kuroda Kiyotaka, leading to the Treaty of Ganghwa.

See also

References

- Medzini, Meron (1971). French Policy in Japan During the Closing Years of the Tokugawa Regime. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-674-32230-1. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Seth, Michael J. (2016). Routledge Handbook of Modern Korean History. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-317-81149-7. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- Annals of Joseon Dynasty, Gojong, Book 3, September 21st, 1866 (고종실록) / Byeong-in Journal (병인일기) and Jungjok-Mountain Fortress Combat Fact(정족산성접전사실) by Yang Heon-su and 6 more

- "Expédition de Corée en 1866, <<Le Spectateur militaire>> (Ch. Martin, 1883) P265

- Pierre-Emmanuel Roux, La Croix, la baleine et le canon: La France face à la Corée au milieu du XIXe siècle, p. 231-275.

- Dallet, 452.

- Source

- Kane (1999), 2.

- "It is estimated than 10,000 were killed within a few months" Source Archived 10 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p.20

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p.20

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p. 21

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p. 21

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p.21

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p.21

- "Expédition de Corée: Extrait du Cahier de Jeanne Frey". In U, Cheolgu, 19 segi yeolgang gwa hanbando [the great powers and the Korean peninsula in 19th century]. (Seoul: Beobmunsa, 1999), p. 216

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p. 22

- Marc Orange, "Expédition de l‘amiral Roze en Corée". Revue du Corée, 30 (Fall 1976), 56.

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p. 23

- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours, p. 23

- Numbers vary according to the source but they are nearly all unanimous in providing the number of French dead. See for instance, Ch. Martin, "Expédition de Corée en 1866". Le Spectateur militaire (1883), p. 265.

- "L'expédition que je viens de faire, si modeste qu'elle soit, en aura préparé une plus sérieuse si elle est jugée nécessaire, ... Elle aura d'ailleurs profondément frappé l'esprit de la Nation Coréenne en lui prouvant que sa prétendue invulnérabilité n'était que chimérique. Enfin la destruction d'un des boulevards de Seoul et la perte considérable que nous avons fait éprouver au gouvernement coréen ne peuvent manquer de le rendre plus circonspect. Le but que je m'étais fixé est donc complètement rempli et le meurtre de nos missionnaires a été vengé" Source Archived 10 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Reuters 12 Nov 2010

- "France has agreed to return on a permanent lease basis a collection of royal documents considered national treasures by South Korea and seized by the French navy in the 19th century, Seoul said on Saturday." Reuters 12 Nov 2010

- Korea Times 29 November 2010

- "S. Korea celebrates return of ancient Korean books from France".

Further reading

- Choe, Chin Young. The Rule of the Taewŏn’gun 1864-1873: Restoration in Yi Korea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972.

- Choi, Soo Bok. "The French Jesuit Mission in Korea, 1827-1866". North Dakota Quarterly 36 (Summer 1968): 17–29.

- Dallet, Charles. Histoire de l'Église de Corée. Paris: Librairie Victor Palmé, 1874. (This epic history of the Catholic Church in Korea is important as well for some of the first depictions of Korea by westerners. It was pulled together by Dallet from letters of the missionaries themselves as well as an earlier draft written by one of the missionaries executed in 1866 that had been smuggled out of the country. Unfortunately, it has never been fully translated into English).

- Kane, Daniel C. "Bellonet and Roze: Overzealous Servants of Empire and the 1866 French Attack on Korea". Korean Studies 23 (1999): 1–23.

- Kane, Daniel C. "Heroic Defense of the Hermit Kingdom". Military History Quarterly (Summer 2000): 38–47.

- Kane, Daniel C. "A Forgotten Firsthand Account of the P'yǒngin yangyo (1866) : An Annotated Translation of the Narrative of G. Pradier." Seoul Journal of Korean Studies. 21:1 (June 2008): 51–86.

- Kim, Youngkoo. The Five Years' Crisis, 1861-1871: Korean in the Maelstrom of Western Imperialism. Seoul: Circle Books, 2001.

- Orange, Marc. "L'Expédition de l;Amiral Roze en Corée". Revue de Corée. 30 (Autumn 1976): 44–84.

- Roux, Pierre-Emmanuel. La Croix, la baleine et le canon: La France face à la Corée au milieu du XIXe siècle. Paris: Le Cerf, 2012.

- Thiébaud, Jean-Marie. La présence française en Corée de la fin du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours. Paris: Harmattan, 2005.

- Wright, Mary C. "The Adaptability of Ch'ing Diplomacy: The Case of Korea." Journal of Asian Studies, May 1958, 363-81. Available through JSTOR.