Franco-Savoyard War (1600–1601)

The Franco-Savoyard War of 1600-1601 was an armed conflict between the Kingdom of France, led by Henry IV, and the Duchy of Savoy, led by Charles Emmanuel I. The war was fought to determine the fate of the former Marquisate of Saluzzo, and ended with the Treaty of Lyon which was favorable to France.

| Franco-Savoyard War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

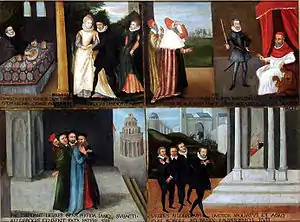

Henry IV and the war of Savoy | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Henry IV of France Charles de Gontaut, Duke of Biron François de Bonne, Duke of Lesdiguières Maximilien de Béthune, Duke of Sully | Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy | ||||||||

Background

Saluzzo was a French enclave in the Piedmontese Alps in the mid-sixteenth century, having been annexed by Henry II of France following the death of the last marquis Gian Gabriele I in 1548. France's claim on the marquisate, however, was relatively weak, and in the 1580s its possession of the territory came to be contested by Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy, who had begun pursuing a policy of expansion for his duchy and sought to acquire Saluzzo for himself. Taking advantage of the civil war weakening France during the reign of his cousin Henry III, Charles Emmanuel occupied Saluzzo in the autumn of 1588, on the pretext of wanting to prevent its occupation at the hands of the Protestant Huguenots of Dauphiné, and continued to hold it for the following twelve years.[1]

In 1595 the French king Henry IV, on the occasion of his visit to Lyons, offered to grant the Marquisate of Saluzzo to one of Charles Emmanuel's sons as a French fief, but the Duke of Savoy insisted on outright possession and rejected the proposal. Papal arbitration of the matter proved to be no more successful, and the issue remained unresolved until December 1599, when the king of France received the Duke of Savoy in Fontainebleau. To resolve the dispute, Henry IV suggested to Charles Emmanuel two alternatives: the return of Saluzzo to France, or to retain the marquisate but to cede in exchange the county of Bresse, the vicarship of Barcelonnette, and the Stura, Perosa, and Pinerolo valleys.[2]

The Duke of Savoy asked for a period of time to make a decision and returned in early 1600 to Turin, where he began preparing for an armed conflict against France. He also sent an envoy to Spain, and was encouraged to hope for Spanish aid from the governor of Milan, Pedro Henriquez de Acevedo, Count of Fuentes. Following the expiration of the decision period, Henry delivered an official ultimatum to the Duke of Savoy, to force his cooperation on the issue. Charles Emmanuel, however, continued to refuse to accede to Henry's demands, whereupon the latter decided to resolve the matter by force and declared war against the duchy in August 1600.[3]

Conflict

Given the superior state of their forces, the French were able to quickly overrun much of Bresse and Savoy. In the first weeks of the conflict, Charles de Gontaut, Duke of Biron, captured Bourg-en-Bresse, although he failed to take its citadel, and proceeded to occupy most of Bresse, the Bugey, and Gex, while François de Bonne, Duke of Lesdiguières' stepson Charles de Blanchefort conquered Montmélian. Chambery opened its gates to Henry's troops a few days later, and Lesdiguières took both the Fortress of Miolans and Conflans. Over the next two months the French continued their advance, taking the Castle of Charbonnières and occupying the Maurienne and Tarentaise valleys, although the Savoyards were able to repulse an attempt to take Nice by Charles, Duke of Guise. In early October Henry made a triumphant entrance into Annecy, and from there made his way to Faverges and Beaufort.[4]

In response to the French invasion, Charles Emmanuel assembled an army of some twenty thousand Piedmontese, Spaniards, Swiss, and Savoyards, and set out from the Aosta Valley for the Tarentaise in early November. Although a French diversionary expedition to the Maira Valley failed to draw him away from his advance (and was subsequently forced to retreat across the Alps after facing resistance from the Marquis d'Este), the duke was unable to make any headway against the French armies in Savoy, who continued their progress in occupying the country. The citadel of Montmélian, which had held out after the fall of the town, surrendered in mid-November, and a month later the fortress of Sainte Catherine, which had been erected to menace the nearby city of Geneva, was taken and demolished by a joint French and Genevese force. By the end of the year all of Bresse and Savoy were in the hands of the French, with the exception of the citadel of Bourg.[5]

Peace

Although France had suffered few losses during the war, the threat of Spanish intervention encouraged Henry to accept offers of peace in early 1601, and the conflict was brought to an end on January 17, 1601 by the Treaty of Lyon. Savoy was compelled to cede most of its territories on the western side of the Rhône, including Bresse, the Bugey, Gex, and Valromey, and paid 300,000 livres to France. In exchange, France formally granted Saluzzo to Savoy, thereby giving up its Italian holdings on the far side of the Alps.[6]

A point of contention during the peace negotiations was the fate of the Spanish Road, which Spain relied upon to link Franche-Comté with Milan. Since the French annexations threatened to close the corridor, an alternative route through the territory of Bern was initially proposed, but was objected to by Geneva on the grounds that it could expose the city to a Spanish attack. At length, the parties agreed on a new route via the Bridge of Grésin, allowing the road to remain open but confining it to a single valley.[7]

Notes

- Armstrong 1905, pp. 412–15; Perceval 1825, p. 415.

- Hardouin de Péréfixe 1896, pp. 204 ff.; Duke of Sully 1805, pp. 291 ff., 313–14; Armstrong 1905, p. 418; Leathes 1905, p. 677.

- Hardouin de Péréfixe 1896, pp. 214-16.

- Alexandre de Saluces 1818, pp. 13–28; Hardy de Périni n.d., pp. 255 ff.; Hardouin de Péréfixe 1896, p. 217.

- Alexandre de Saluces 1818, pp. 28 ff.; Hardy de Périni n.d., pp. 269–70; Armstrong 1905, p. 418.

- Armstrong 1905, pp. 418–19; Leathes 1905, p. 677; Hardy de Périni n.d., pp. 270–71.

- Parker 2004, pp. 58-59.

References

- Alexandre de Saluces (1818). Histoire militaire du Piémont, Tome Troisième (in French). Turin: L'Académie Royale Des Sciences.

- Armstrong, Edward (1905). "Tuscany and Savoy". In Ward, A. W.; Prothero, G. W.; Leathes, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Modern History, Volume III. Cambridge: Macmillan & Co.

- Duke of Sully, Maximilien de Béthune (1805). Memoirs of Maximilian de Bethune, Duke of Sully, Prime Minister of Henry the Great, Volume II. Trans. Charlotte Lennox. Edinburgh: Alexander Lawrie & Co.

- Hardouin de Péréfixe de Beaumont (1896). The History of Henry IV, (surnamed "the Great"), King of France and Navarre. Trans. James Dauncey. London: H. S. Nichols.

- Hardy de Périni (n.d.). Batailles françaises: De François il à Louis XIII, 1562 à 1620 (in French). Chateauroux: A. Majesté et L. Bouchardeau.

- Leathes, Stanley (1905). "Henry IV of France". In Ward, A. W.; Prothero, G. W.; Leathes, Stanley (eds.). The Cambridge Modern History, Volume III. Cambridge: Macmillan & Co.

- Parker, Geoffrey (2004). The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659: The Logistics of Spanish Victory and Defeat in the Low Countries' Wars (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83600-X.

- Perceval, George (1825). The History of Italy, From the Fall of the Western Empire to the Commencement of the Wars of the French Revolution, Volume II. London: R. Gilbert.